The Early History of the Monastery of Cluny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

St. Odo of Cluny Catholic.Net

St. Odo of Cluny Catholic.net Born to the nobility, the son of Abbo. Raised in the courts of Count Fulk II of Anjou and Duke William of Aquitaine. Received the Order of Tonsure at age nineteen. Canon of the church of Saint Martin of Tours. Studied music and theology in Paris for four years, studying under Remigius of Auxerre. Returning home, he spent years as a near-hermit in a cell, studying and praying. Benedictine monk at Baume, diocese of Besancon, France in 909, bringing all his worldly possessions – a library of about 100 books. Spiritual student of the abbot, Saint Berno of Cluny. Headmaster of the monastery school at Baume. Abbot of Baume in 924. Abbot of Cluny, Massey and Deols in 927. In 931, Pope John XI asked Odo to reform all the monasteries in the Aquitaine, northern France and Italy. Negotiated a peace between Heberic of Rome and Hugh of Provence in 936; returned twice in six years to renegotiate the peace between them. Persuaded many secular leaders to give up control of monasteries so they could return to being spiritual centers, not sources of cash for the state. Founded the monastery of Our Lady on the Aventine in Rome. Wrote a biography of Saint Gerald of Aurillac, three books of essays on morality, some homilies, an epic poem on the Redemption, and twelve choral antiphons in honour of Saint Martin of Tours. Noted for his knowledge, his administrative abilities, his skills as a reformer, and as a writer; also known for his charity, he has been depicted giving the poor the clothes off his back. -

Cistercian Preparatory School: the First 50 Year

CISTERCIAN PREPARATORY SCHOOL THE FIRST 50 YEARS 1962 2012 David E. Stewart Headmasters CISTercIAN PreparaTORY SCHOOL 1962 - 2012 Fr. Damian Szödényi, 1962 - 1969 Fr. Denis Farkasfalvy, 1969 - 1974 Fr. Henry Marton 1974 - 1975 Fr. Denis Farkasfalvy, 1975 - 1981 Fr. Bernard Marton, 1981 - 1996 Fr. Peter Verhalen ’73, 1996 - 2012 Fr. Paul McCormick, 2012 - Fr. Damian Szödényi Fr. Henry Marton Headmaster, 1962 - 1969 Headmaster, 1974 - 1975 (b. 1912, d. 1998) (b. 1925, d. 2006) Pictured on the cover (l-r): Fr. Bernard Marton, Abbot Peter Verhalen ’73, Fr. Paul McCormick, and Abbot Emeritus Denis Farkasfalvy. Cover photo by Jim Reisch CISTERCIAN PREPARATORY SCHOOL THE FIRST 50 YEARS David E. Stewart ’74 Thanks and acknowledgements The heart of this book comes from over ten years of stories published in The Continuum, the alumni magazine for Cistercian Prep School. Thanks to Abbot Peter Verhalen and Abbot Emeritus Denis Farkasfalvy and many other monks, faculty members, staff, alumni, and parents for their trust and willingness to share so much in the pages of the magazine and this book. Christine Medaille contributed her time and talent to writing Chapter 8 and Brian Melton ’71 contributed mightily to Chapter 11. Thanks to Jim Reisch for his outstanding photography throughout this book, and especially for the cover shot. Priceless moments from the sixties were captured by or provided by Jane Bret and Fr. Melchior Chladek. Thanks to Rodney Walter for collecting the yearbook photographs used in the book and identifying the students in them. Thanks to Fr. Bernard Marton, Sylvia Najera, and Bridgette Gimenez for their help in editing and proofing. -

In Any Given Moment

Gradually, gradually, A moment at a time, The wise remove their own impurities As a goldsmith removes the dross. Dhammapada verse 239 in any given moment Ajahn Munindo In Any Given Moment by Ajahn Munindo This publication is made available for free distribution by Aruno Publications Aruno Publications is administered by: Harnham Buddhist Monastery Trust Company No. 6688355, Charity Reg. No. 1126476 Contact Aruno Publications at www.ratanagiri.org.uk This book is available for free download at www.forestsangha.org ISBN 978-1-908444-69-1 Copyright © Aruno Publications 2021 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Produced with the LATEX typesetting system, set in EB Garamond, Alegreya Sans and Merriweather. First edition, 2021 CONTENTS Preface x i TAKING SHAPE 1 1 . 1 The End of the River 3 1 . 2 Being Different 7 1 . 3 Doctor Albert Schweitzer 1 1 1 . 4 Difficult Lessons 1 7 1 . 5 Getting Ready to Leave 2 5 YEARS OF CHAOS 2 9 2 . 1 Out Into the World 3 1 2 . 2 Jumping Sundays 3 5 2 . 3 Lifelines 4 1 2 . 4 Journeying 5 1 2 . 5 Ready to Leave, Again 5 9 2 . 6 A Very Foreign Country 6 1 THE SPIRIT OF THE SPIRITUAL LIFE 6 9 3 . 1 A Reorientation 7 1 3 . 2 What Next? 7 5 3 . 3 Heading For Asia 8 1 3 . 4 Dark Clouds Descending 8 9 3 . 5 The Land of the Free 9 5 3 . 6 Different Perspectives 9 9 3 . 7 First Encounter with the Forest Sangha 1 1 3 3 . -

Liber Petri Mathie Curati Ecclesie Sancti Petri Ripis

LIBER PETRI MATHIE CURATI ECCLESIE SANCTI PETRI RIPIS THE BOOK OF PEDER MADSEN, CURATE AT ST. PETER'S CHURCH IN RIBE 1454 - 1483 Msc. Ny kgl. Samling 123 4o, The Royal Library, Copenhagen transscribed by ANNE RIISING TABLE OF CONTENTS FRONTISPICE TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................ 8 The author and his work .........................................................................................................8 A call to rebellion against certain editorial principles............................................................ 8 Spelling and punctuation......................................................................................................... 8 Brackets and italics.................................................................................................................. 8 Indices: Biblical qotations........................................................................................................ 8 Authorities quoted ................................................................................................................... 8 Names ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Places....................................................................................................................................... -

Blogs 2018 SPRING.Pdf

1 Dharma Blogs 2018 SPRING By Michael Erlewine 2 INTRODUCTION This is not intended to be a finely produced book, but rather a readable document for those who are interested in my particular take on dharma training and a few other topics. These blogs were from the Spring of 2018 posted on Facebook and Google+. [email protected] Here are some other links to more books, articles, and videos on these topics: Main Browsing Site: http://SpiritGrooves.net/ Organized Article Archive: http://MichaelErlewine.com/ YouTube Videos https://www.youtube.com/user/merlewine Spirit Grooves / Dharma Grooves Copyright 2018 © by Michael Erlewine You are free to share these blogs provided no money is charged Cover image is Vajradhara 3 Contents WHEN NOT-ENOUGH IS ENOUGH .......................... 9 FORCED INTO AWAKENING .................................. 11 LIBERATION THROUGH SEEING .......................... 14 DHARMA PRACTICE AND BOREDOM ................... 18 EQUINOX CRACKS: TASERS FROM THE SUN .... 22 THE FLAME AND THE SELFIE ............................... 24 DHARMA’S COLD COMFORT ................................ 27 DHARMA: BEYOND THE TURNING POINT ........... 30 BEING ALONE: “I’M JUST A LONELY BOY” ........... 34 KARMA: THOSE DEEP DOWN STUBBORN STAINS ................................................................................. 37 THE STOREHOUSE CONSCIOUSNESS: KARMA CHAMELEON .......................................................... 40 WHEN IN DOUBT, RIDE THE MOON CYCLE ........ 45 FORCING FACTS: ASTROLOGY IS CULTURAL ASTRONOMY ......................................................... -

Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant As Corporate Knowledge

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2012 "Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge Jordan Timothy Ray Baker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Epistemology Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Jordan Timothy Ray, ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1360 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jordan Timothy Ray Baker entitled ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Rachel M. Golden, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: -

The Light from the Southern Cross’

A REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIOCESES AND PARISHES IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA IMPLEMENTATION ADVISORY GROUP AND THE GOVERNANCE REVIEW PROJECT TEAM REVIEW OF GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIOCESES AND PARISHES REPORT – STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Let us be bold, be it daylight or night for us - The Catholic Church in Australia has been one of the epicentres Fling out the flag of the Southern Cross! of the sex abuse crisis in the global Church. But the Church in Let us be fırm – with our God and our right for us, Australia is also trying to fınd a path through and out of this crisis Under the flag of the Southern Cross! in ways that reflects the needs of the society in which it lives. Flag of the Southern Cross, Henry Lawson, 1887 The Catholic tradition holds that the Holy Spirit guides all into the truth. In its search for the path of truth, the Church in Australia And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness seeks to be guided by the light of the Holy Spirit; a light symbolised of the sky above; and those who turn many to righteousness, by the great Constellation of the Southern Cross. That path and like the stars forever and ever. light offers a comprehensive approach to governance issues raised Daniel, 12:3 by the abuse crisis and the broader need for cultural change. The Southern Cross features heavily in the Dreamtime stories This report outlines, for Australia, a way to discern a synodal that hold much of the cultural tradition of Indigenous Australians path: a new praxis (practice) of church governance. -

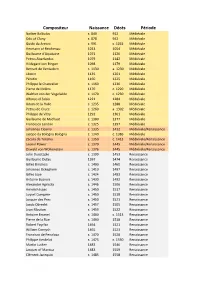

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

Sacred Heart Enthronement

CatholicThe TIMES The Diocese of Columbus’ News Source June 16, 2019 • SOLEMNITY OF THE MOST HOLY TRINITY• Volume 68:34 Inside this issue Right to Life banquet: Dr. William Lile discussed the abortion pill reversal drug at the annual Greater Columbus Right to Life banquet, Page 3 Trinity & Corpus Christi: Father Timothy Hayes reflects on the spiritual richness of Holy Trinity and Corpus Christi Sundays to close out the month of June, Page 16 Catholic summer travel: You don’t have to go outside Ohio’s borders to find plenty of Catholic pilgrimage sites for a day trip, Pages 21-23 SACRED HEART ENTHRONEMENT: A DEVOTION GROWING IN SUPPORT Pages 12-15 Catholic Times 2 June 16, 2019 Local news and events West Deanery to celebrate Feast of Corpus Christi on June 23 Grove City Our Lady of Perpetual invited to participate in the event. ipate being ordained in 2020, and all Mass at noon Sunday, preceded by the Help Church, 3730 Broadway, will They should bring their own albs or of the deanery’s parishes except St. rosary and followed by lunch. host the West Deanery’s 23rd annu- cassocks and surplices. All 2019 first Aloysius have regularly scheduled Child care will be provided during al celebration of the Feast of Corpus communicants and their families also times of Eucharistic Adoration. all the main sessions, with a nursery Christi on Sunday, June 23. are welcome to participate. The chil- for children three months to 2 years Exposition of the Blessed Sacra- dren can wear their dresses or suits. Scioto parishes sponsor family old and Kids Camp for those from pre- ment will take place from the end of In 1997, pastors of the West Dean- conference school to fifth grade. -

Catholic Liturgical Calendar †

Catholic Liturgical Calendar January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2018 FOR THE DIOCESES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 2018 ⚭ † ☧ 2 JANUARY 2018 1 Mon SOLEMNITY OF MARY, THE HOLY MOTHER OF GOD white Rank I The Octave Day of the Nativity of the Lord Solemnity [not a Holyday of Obligation] Nm 6:22-27/Gal 4:4-7/Lk 2:16-21 (18) Pss Prop Solemnity of Mary, the Holy Mother of God (Theotokos) The Octave Day of the Nativity of the Lord Solemnity of Mary, the Holy Mother of God (Theotokos) “From most ancient times the Blessed Virgin has been venerated under the title ‘God- bearer’(Theotokos)” (Lumen Gentium, no. 66). All of the Churches recall her memory under this title in their daily Eucharistic prayers, and especially in the annual celebration of Christmas. The Virgin Mary was already venerated as Mother of God when, in 431, the Council of Ephesus acclaimed her Theotokos (God-bearer). As the Mother of God, the Virgin Mary has a unique position among the saints, indeed, among all creatures. She is exalted, yet still one of us. Redeemed by reason of the merits of her Son and united to Him by a close and indissoluble tie, she is endowed with the high office and dignity of being the Mother of the Son of God, by which account she is also the beloved daughter of the Father and the temple of the Holy Spirit. Because of this gift of sublime grace she far surpasses all creatures, both in heaven and on earth. At the same time, however, because she belongs to the offspring of Adam she is one with all those who are to be saved. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy.