Hermann Hesseâ•Žs Creation of a Modern Saint in Peter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Reading St. Pius X Regional School 2019 Reading Lists Summer Reading for Grades 5

Summer Reading St. Pius X Regional School 2019 Reading Lists Summer reading for grades 5 - 8 is required: ▪ Each student entering Grade 5 must read 2 books from the fifth grade list and return the applicable signed forms to their Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. This is a graded activity. ▪ Each student entering Grades 6-8 must read 2 books. One of the two books must be chosen from the appropriate grade list of fiction titles. (see below for the list of acceptable titles for each grade) The second books MUST be a BIOGRAPHY with a minimum of 100 pages of their choosing, some are listed. Students must return both applicable signed forms to the Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. This is a graded activity. ▪ All reading lists and forms will be available on the St. Pius website about June 17th. ▪ All lists and forms are below. ST. PIUS X - SUMMER READING Incoming Grade 8 (2019) 1. Each student entering Grade 8 must read 2 books. One of the two books must be chosen from the appropriate grade list of fiction titles. (see below for the list of acceptable titles for 8th grade) 2. The second books MUST be a BIOGRAPHY with a minimum of 100 pages of their choosing, some are listed. 3. Students must return the applicable signed forms (one form for the fiction title and one form for the biography title) to the Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. (both forms are below) 4. -

SJU Semester Abroad Policy

Saint Joseph's University Semester Abroad Policy Please be advised that starting with the fall 2003 semester, the following policy will be in effect for Saint Joseph’s University students who wish to study abroad and receive credit toward their Saint Joseph’s degree. Under this policy, students will remain registered at SJU and pay SJU full-time, day tuition plus a $100 Continuing Registration Fee for each semester they will be studying abroad. Students will be considered enrolled at Saint Joseph’s University while abroad and will be allowed to receive his/her entire financial aid package. Saint Joseph’s University will then pay the overseas program for the tuition portion of the program. Students will be responsible for all non-tuition fees associated with the program they will be attending. Please note that for some Saint Joseph’s University affiliated programs, students may be required to pay other fees to Saint Joseph’s University first and Saint Joseph’s University will then forward these fees to the program sponsor. Students must receive proper approval for their proposed program of study. Upon successful completion of an approved foreign program of study, credit will be granted towards graduation for all appropriate courses taken on SJU approved programs. APPLICATION PROCESS Students must apply through and receive approval from the Center for International Programs (CIP) in order to study abroad. The on-line application cycle for the fall term typically opens in January and closes in mid- February or on March 1st (depending on the program). The on-line application cycle for the spring term typically opens in late-August and closes in mid-September or on October 1st (again, depending on the program). -

St. Odo of Cluny Catholic.Net

St. Odo of Cluny Catholic.net Born to the nobility, the son of Abbo. Raised in the courts of Count Fulk II of Anjou and Duke William of Aquitaine. Received the Order of Tonsure at age nineteen. Canon of the church of Saint Martin of Tours. Studied music and theology in Paris for four years, studying under Remigius of Auxerre. Returning home, he spent years as a near-hermit in a cell, studying and praying. Benedictine monk at Baume, diocese of Besancon, France in 909, bringing all his worldly possessions – a library of about 100 books. Spiritual student of the abbot, Saint Berno of Cluny. Headmaster of the monastery school at Baume. Abbot of Baume in 924. Abbot of Cluny, Massey and Deols in 927. In 931, Pope John XI asked Odo to reform all the monasteries in the Aquitaine, northern France and Italy. Negotiated a peace between Heberic of Rome and Hugh of Provence in 936; returned twice in six years to renegotiate the peace between them. Persuaded many secular leaders to give up control of monasteries so they could return to being spiritual centers, not sources of cash for the state. Founded the monastery of Our Lady on the Aventine in Rome. Wrote a biography of Saint Gerald of Aurillac, three books of essays on morality, some homilies, an epic poem on the Redemption, and twelve choral antiphons in honour of Saint Martin of Tours. Noted for his knowledge, his administrative abilities, his skills as a reformer, and as a writer; also known for his charity, he has been depicted giving the poor the clothes off his back. -

Edward the Saint Elena G

Year 2007 Article 19 1-1-2007 Edward the Saint Elena G. Mailander Gettysburg College, [email protected] Class of 2009 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/mercury Part of the Poetry Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Mailander, Elena G. (2015) "Edward the Saint," The Mercury: Year 2007, Article 19. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/mercury/vol2007/iss1/19 This open access poetry is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edward the Saint Keywords creative writing, poetry Author Bio Elena Mailander hails from the far-off al nd of Reno, Nevada. She likes to write, draw, listen to music, and daydream. She is studying Japanese and studio art, and is currently pursuing a career as a comic book artist. This poetry is available in The eM rcury: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/mercury/vol2007/iss1/19 ELENA MAILANDER Edward the Saint In 1887, the “safety bicycle” hit the shelves: with its two identical owl-eye wheels, it promised that, New York or Alabama, dirt or asphalt, if, or inevitably when, you fell from its height, you wouldn’t hurt yourself. Well...all that badly. But falling from a bicycle is much different from falling into life. Into someone’s waiting hands. Both can be catastrophic, if you make them, when you emphasize the flaws - the rocks - the yellow curtains - the passing motorcar - a pressed flower album And growing up is no easy chore, for then you’ve got the added risk of others on the road. -

Read Book the Saint Returns

THE SAINT RETURNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Leslie Charteris | 212 pages | 24 Jun 2014 | Amazon Publishing | 9781477842980 | English | Seattle, United States The Saint Returns PDF Book Create outlines for what you want to be accomplished. This was scrapped, and Ian Ogilvy took over the halo for 24 episodes as Simon Templar. This amount is subject to change until you make payment. He also somewhat deplored the tendency for the Saint to be seen primarily as a detective, and this was even stated in some of the later stories, e. Reading about Charteris' "amiable rascal" is infinitely easier and much more relaxing than writing more stories about my own fictitious rascal, Misfit Lil whom I like to think shares a trait or two with Mr Simon Templar! Honestly it was probably the highlight of an episode that mostly spun its wheels. Alyssa Milano legs boots feet Chad Allen magazine pin up clipping. Balthazar Getty Alyssa Milano magazine clipping pin up s vintage. He steals from rich criminals and keeps the loot for himself usually in such a way as to put the rich criminals behind bars. He threatens the biggest explosion of all unless sculptress Lynn Jackson is Hell In order for Eugene and Hitler to get out of hell, Eugene has to overcome the thing that has been keeping him in Hell. Simon Templar 24 episodes, The Saint also ventured into the comics section of our newspapers, battling alongside Dick Tracy and the other Sunday heroes. Seller's other items. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. -

St. Teresaof Avila the Co-Cathedral of Saint Joseph

MASS SCHEDULE Sunday 9:00 AM - Creole 11:00 AM - English 1:30 PM - Spanish THE Weekdays CO-CATHEDRAL 8:00 AM - English 8:30 AM - Creole OF SAINT JOSEPH 9:00 AM - Spanish TH JULY 11 , 2021 CO-CATHEDRAL AND ST. TERESA STAFF ITE AD JOSEPH: GO TO JOSEPH RECTOR The Reverend Christopher R. Heanue [email protected] Earlier this year, beginning on February 15, I started a PAROCHIAL VICAR 33 day consecration to Saint Joseph. Using an insightful The Reverend Pascal Louis book by Fr. Donald Calloway, MIC, I prayed the en- [email protected] tire consecration and grew in my knowledge and love PRIESTS IN RESIDENCE of Saint Joseph. The 33 day consecration ended on the The Reverend Monsignor Sean G. Ogle feast of Saint Joseph, March 19. The Reverend Sebastián Sardo Providentially, two months later, I received a phone call DEACON from Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio informing me that I Deacon Fausto Duran was being assigned as the next Rector of the Co-Cathe- [email protected] dral of Saint Joseph! DEACON/RCIA DIRECTOR Deacon Manuel H. Quintana “Go to Joseph”, the people of Egypt were told. “Do [email protected] whatever he tells you” (Genesis 41:55). RELIGIOUS EDUCATION Ms. Jessica Figueroa I promise to hold these words close to my heart as I [email protected] begin this ministry here at the Co-Cathedral of Saint Mrs. Brenda Donald Joseph - Saint Teresa of Avila Parish. [email protected] Both the Joseph of the Old Testament and Saint Joseph, the foster-father of Jes- PARISH SECRETARY Fabiola Edmond us, were exemplary leaders and men of great courage. -

Ofelia the Saint

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2019-01-01 Ofelia the Saint Samuel H. Duarte University of Texas at El Paso Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Duarte, Samuel H., "Ofelia the Saint" (2019). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2915. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2915 This is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OFELIA THE SAINT SAMUEL H. DUARTE Master’s Program in Creative Writing APPROVED: _________________________________ Jose De Pierola, Ph.D., Chair _________________________________ Paula Cucurella Lavin, Ph.D. _________________________________ Hilda Ontiveros-Harrieta ___________________________________ Stephen L. Crites, Jr., Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School © 2019 Samuel H. Duarte, All Rights Reserved To my parents, Francisco and Soledad Duarte, and to Ofelia. OFELIA THE SAINT by OFELIA THE SAINT By SAMUEL DUARTE THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Department of Creative Writing THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CRITICAL PREFACE…………………………………………………………………………...vi PROLOGUE……………………………………………………………………………………..xv -

The Inventory of the Leslie Charteris Collection

The Inventory of the Leslie Charteris Collection #39 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center charteris.inv CHARTERIS, LESLIE (1907-1993) Addenda, July 1972 - 1993 [13 Paige boxes, Location: SB2G] I. MANUSCRIPTS Box 1 Scripts bound. "The Saint Show." Volumes 1-12. Radio scripts, 1945-1948. "The Fairy Tale Murder." n.d. "Lady on a Train." Film script, 1943. "Two Smart People" by LC and Ethel Hill, 1944. Box 2 "Return of the Saint" TV Series. 1970s. "Appointment in Florence" "Armageddon Alternative" "The Arrangement" "Assault Force" "The Debt Collectors" "The Diplomats Daughter" "Double Take" "Dragonseed" "Duel in Venice" "The Imprudent Professor" "The Judas Game" "Lady on a Train" 1 "The Murder Cartel" "The Nightmare Man" "The Obono Affair" "One Black September" "The Organisation Man" "The Poppy Chain" Box 2 "Prince of Darkness" "The Roman Touch" "Tower Bridge is Falling Down" "Vanishing Point" Part 1 The Salamander Part 2 The Sixth Man "Vicious Circle" "The Village that Sold Its Soul" "Yesterday's Hero" "The Saint" series, 1989. "The Big Bang" "The Blue Dulac" "The Brazilian Connection" "The Software Murders" Synopses for "Saint" scripts with reply 1972, 3 1973, 2 1974, 6 1975, 5 1976, 3 1977, 3 1978, 1 1979, 8 1980, 6 1981, 7 2 1982, 7 1983, 6 1984, 4 1985, 3 1986, 1 1987, 1 1988, 1 Synopses without reply 1962, 1 1971, 1 1973, 3 1974, 1 1977, 1 1978, 2 1981, 1 1983, 5 1984, 6 1987, 1 Eight undated Synopses Box 3 Radio scripts (unbound):#16, 28, 33, 37, 38, 41, 43, 45, 46, and two without numbers. -

Read Doc \ the Saint in Miami

28SKZSH2HU8N > eBook \\ The Saint in Miami The Saint in Miami Filesize: 2.75 MB Reviews This type of book is almost everything and helped me hunting forward and more. I was able to comprehended almost everything using this published e pdf. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Edwardo Ziemann) DISCLAIMER | DMCA VYI7LB9AYKWO \ Book ^ The Saint in Miami THE SAINT IN MIAMI Audible Studios on Brilliance, 2015. CD-Audio. Condition: New. Unabridged. Language: English . Brand New. Simon Templar is the Saint daring, dazzling, and just a little disreputable. On the side of the law, but standing outside it, he dispenses his own brand of justice one criminal at a time. The Saint and Patricia go to visit some friends in Miami but when they get there they are shocked to learn their friends have disappeared. They move into their friends house and start to investigate. Things get complicated when a tanker explodes o the Florida coast and a dead British sailor washes up on the shore. Simon suspects a link between the explosion and the disappearance, as well as the activities of shady millionaire Randolph March. There seems to be a Nazi spy ring operating out of Florida . Leslie Charteris was born in Singapore and moved to England in 1919. He le Cambridge University early when his first novel was accepted for publication. He wrote novels about the Saint throughout his life, becoming one of the 20th century s most prolific and popular authors. Read The Saint in Miami Online Download PDF The Saint in Miami 5NUROAQZNQXZ < Kindle ^ The Saint in Miami Related Kindle Books Abraham Lincoln for Kids: His Life and Times with 21 Activities Chicago Review Press. -

Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant As Corporate Knowledge

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2012 "Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge Jordan Timothy Ray Baker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Epistemology Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Jordan Timothy Ray, ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1360 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jordan Timothy Ray Baker entitled ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Rachel M. Golden, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: -

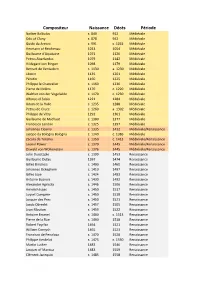

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

Find PDF > Saint Overboard

NCLWTTVKIHXZ > PDF Saint Overboard Saint Overboard Filesize: 1.53 MB Reviews Thorough guide for pdf enthusiasts. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. Its been printed in an remarkably simple way which is only soon after i finished reading through this pdf by which really altered me, change the way i believe. (Dr. Rowena Wiegand) DISCLAIMER | DMCA CBJHFWSI5IWI < PDF ^ Saint Overboard SAINT OVERBOARD Hodder & Stoughton General Division. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Saint Overboard, Leslie Charteris, How could the Saint possibly resist the chance of a treasure hunt? When his sailing trip along the French coast is interrupted by gunfire and shouting, naturally he gets curious. The cause of the commotion is a group of men pursuing a young woman - and once Simon steps in to help the damsel in distress, he soon finds himself on the trail of a group of modern-day pirates - and searching for a huge amount of gold. Read Saint Overboard Online Download PDF Saint Overboard OBLOPD8C0SZV // eBook Saint Overboard You May Also Like TJ new concept of the Preschool Quality Education Engineering the daily learning book of: new happy learning young children (3-5 years) Intermediate (3)(Chinese Edition) paperback. Book Condition: New. Ship out in 2 business day, And Fast shipping, Free Tracking number will be provided aer the shipment.Paperback. Pub Date :2005-09-01 Publisher: Chinese children before making Reading: All books are the... Download ePub » TJ new concept of the Preschool Quality Education Engineering the daily learning book of: new happy learning young children (2-4 years old) in small classes (3)(Chinese Edition) paperback.