Local Climate Governance in England and Germany: Converging Towards a Hybrid Model?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIGITAL CITIES CHALLENGE Digital Transformation Strategy for the City of Gelsenkirchen Drilling for OIL 2.0

DIGITAL CITIES CHALLENGE – Digital Transformation Strategy DIGITAL CITIES CHALLENGE Digital Transformation Strategy for the city of Gelsenkirchen Drilling for OIL 2.0 July 2019 1 DIGITAL CITIES CHALLENGE – Digital Transformation Strategy Digital Cities Challenge Digital Transformation Strategy for the city of Gelsenkirchen: Drilling for OIL 2.0 Manfred vom Sondern (CDO City Administration) Andreas Piwek (European affairs) Michael Sparenberg (expert for internet security) Lukas Rissel (senior assistant) Sebastian Goerke (assistant) with the contributions of the Digital City leadership team Ieva Savickaite (support consultant) 2 DIGITAL CITIES CHALLENGE – Digital Transformation Strategy Table of contents Executive Summary: Gelsenkirchen’s digital transformation ............................................ 4 1. Introduction to the Digital Cities Challenge .................................................................. 7 2. Overview of the digital maturity assessment for Gelsenkirchen ............................... 9 3. Mission and Ambition statements ............................................................................... 10 4. Drilling for OIL 2.0: The Digital Transformation Strategy for the city of Gelsenkirchen ......................................................................................................................... 11 4.1. Strategy orientation .............................................................................................. 11 4.2. Operational objectives ......................................................................................... -

Terra Bella Community Plan

TERRA BELLA COMMUNITY PLAN TERRA BELLA COMMUNITY PLAN 2015 UPDATE 1 TERRA BELLA COMMUNITY PLAN 2 TERRA BELLA COMMUNITY PLAN Terra Bella Community Plan 2015 Update Adopted Tulare County Board of Supervisors November 3, 2015 Resolution No. 2015-0909 RR County of Tulare Resource Management Agency 5961 S Mooney Boulevard Visalia, CA 93277-9394 (559) 624-7000 3 TERRA BELLA COMMUNITY PLAN 4 Tulare County Board of Supervisors Allen Ishida – District 1 Pete Vander Poel – District 2 Phillip Cox – District 3 Steve Worthley – District 4 (Chairman) Mike Ennis – District 5 (Vice Chairman) Tulare County Planning Commission John F. Elliott – District 1 Nancy Pitigliano – District 2 (Vice Chair) Bill Whitlatch – District 3 Melvin K. Gong – District 4 (Chair) Wayne O. Millies – District 5 Ed Dias – At Large Vacant – At Large Gil Aguilar – District 2 (Alternate) Tulare County Resource Management Agency Michael C. Spata, Director Michael Washam, Assistant Director of Planning Benjamin Ruiz, Jr., Assistant Director of Public Works Reed Schenke, Chief Engineer, Special Programs Eric Coyne, Economic Development Coordinator Aaron R. Bock, Chief Planner, Project Review Hector Guerra, Chief Planner, Environmental Planning David Bryant, Chief Planner, Special Projects Sung H. Kwon, Planner IV (Principal Author) Richard Walker, Planner IV Jessica Willis, Planner IV Chuck Przybylski, Planner III Susan Simon, Planner III Roberto Lujan, Geographic Information Systems Analyst I Tim Hood, Geographic Information Systems Analyst I Kyria Martinez, Economic Development Analyst II Jose A. Saenz, Planner II BOARD OF SUPERVISORS RESOLUTION No. 2015-0909 TERRA BELLA COMMUNITY PLAN TERRA BELLA COMMUNITY PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 9 LOCATION ............................................................................................ 10 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE .................................................................... 10 THE NEED FOR A COMMUNITY PLAN .................................................. -

Entscheidungsgründe

Postadresse: Erdbergstraße 192 – 196 1030 Wien Tel: +43 1 601 49 – 0 Fax: +43 1 711 23-889 15 41 E-Mail: [email protected] www.bvwg.gv.at Entscheidungsdatum 18.02.2021 Geschäftszahl G312 2191725-1/11E IM NAMEN DER REPUBLI K! Das Bundesverwaltungsgericht hat durch die Richterin Mag. Manuela WILD als Einzelrichterin über die Beschwerde XXXX alias XXXX, geb. XXXX, StA. Irak, vertreten durch die BBU GmbH, gegen den Bescheid des Bundesamtes für Fremdenwesen und Asyl – Regionaldirektion XXXX – vom XXXX, Zl. XXXX, nach Durchführung einer mündlichen Verhandlung am 28.12.2020, zu Recht erkannt: A) I. Die Beschwerde wird hinsichtlich Spruchpunkte I. und II. des angefochtenen Bescheides als unbegründet abgewiesen. II. Der Beschwerde wird hinsichtlich Spruchpunkt III. und IV. stattgegeben und eine Rückkehrentscheidung auf Dauer für unzulässig erklärt. XXXX alias XXXX, geb. XXXX wird der Aufenthaltstitel "Aufenthaltsberechtigung plus" für die Dauer von 12 Monaten erteilt. III. Die Spruchpunkte V. - VI. werden ersatzlos aufgehoben. B) Die Revision ist gemäß Art. 133 Abs. 4 B-VG nicht zulässig. Entscheidungsgründe : I. Verfahrensgang: 1. Mit Bescheid des Bundesamtes für Fremdenwesen und Asyl (im Folgenden: belangte Behörde) vom XXXX, Zl. XXXX, wurde der Antrag von XXXX alias XXXX, geb. XXXX (in weiterer Folge: BF) vom XXXX auf internationalen Schutz hinsichtlich der Zuerkennung des Status des - 2 - Asylberechtigten gemäß § 3 Abs. 1 AsylG (Spruchpunkt I.) und hinsichtlich der Zuerkennung des Status des subsidiär Schutzberechtigten gemäß § 8 AsylG in Bezug auf den Herkunftsstaat Irak (Spruchpunkt II.) abgewiesen. Ein Aufenthaltstitel aus berücksichtigungswürdigen Gründen wurde gemäß § 57 AsylG nicht erteilt (Spruchpunkt III.). Gemäß § 10 Abs. 1 Z 3 AsylG iVm § 9 BFA-VG wurde gegen den BF eine Rückkehrentscheidung gemäß § 52 Absatz 2 Z 2 FPG erlassen (Spruchpunkt IV.) und gemäß § 52 Abs. -

DRAFT MINUTES of the Meeting in Strasbourg on 10 March 1989

*** * * PACECOM078101 * * COUNCIL * A * CONSEIL OF EUROPE * * DE L'EUROPE Parliamentary Assembly Assemblee parlementaire Strasbourg, 15 March 1989 CONFIDENTIAL AALPRIXPV2.40 AS/Loc/Prix (40) PV 2 COMMITTEE ON THE ENVIRONMENT, REGIONAL PLANNING AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES Sub-Committee on the Europe Prize DRAFT MINUTES of the meeting in Strasbourg on 10 March 1989 PRESENT MM AHRENS, Chairman Federal Republic of Germany JUNG, President of the Assembly France HARDY, Chairman of the Committee United Kingdom Lord NEWALL (for Lord Kinnoull) United Kingdom MM THOMPSON United Kingdom VARA Portugal ZIERER Federal Republic of Germany APOLOGISED FOR ABSENCE MM ALEMYR Sweden BLENK Austria Mrs BROGLE-SELE Liechtenstein MM CACCIA Fulvio Switzerland LACOUR France ROBLES OROZCO Spain 20.455 01.52 Forty years Council of Europe Quarante ans Conseil de I'Europe AS/Loc/Prix (40) PV 2 - 2 - The meeting was opened by Mr Ahrens, Chairman, at 9.30 am. 1. AGENDA [AS/Loc/Prix (40) OJ 2] The draft agenda was adopted. 2. MINUTES [AS/Loc/Prix (40) PV 1] Mr Thompson said that the minutes eroneously stated that he had attended the meeting. Amended in this respect, the draft minutes of the meeting in Aalborg on 22 August 1988 were adopted. 3. EUROPE PRIZE, PLAQUES OF HONOUR, FLAGS OF HONOUR AND EUROPEAN DIPLOMAS a. Consideration of candidatures for the Europe Prize The Chairman reminded members of the principle of the Europe Prize, which was awarded annually to a community which had already received a flag of honour and had been a regular candidate for the Europe Prize. Mr Ahrens went through the 13 candidatures proposed by the Secretariat and suggested that the prize be awarded either to the Italian municipality or to one of the French municipalities. -

Environmental Quality in Urban Settlement: the Role of Local Community Association in East Semarang Sub-District

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 135 ( 2014 ) 31 – 35 CITIES 2013 Environmental Quality in Urban Settlement: The Role of Local Community Association in East Semarang Sub-District Nany Yuliastutia*,Novi Saraswatib* aUrban and Regional Planning, Diponegoro University; Indonesia bUrban and Regional Planning, Diponegoro University; Indonesia Abstract Society is one of the influential stakeholders in shaping the quality of neighborhoods. Efforts to improve the quality of the environment with the involvement of community empowerment is one of the improvement process, extracting local resources, as well as giving a greater role to the public. This role can be seen from handling environment, such as village improvement, renovation and improvement of the quality environment.Local institutions communities in Indonesia known as the Neighborhood Unit (Rukun Tetangga called RT) drives the self-help community play a role in changes in the quality of residential environment.Priority is determined by the needs of the community programs that are approved by members. Kelurahan Karangturi implement environmental programs larger than the other program components. This paper is a quantitative approach with variable formulation and implementation role of local institutions in the quality of residential neighborhoods in the region in three urban locations.While in the Kelurahan Bugangan greater economic program. In the Kelurahan Kemijen, also dominates the implementation of environmental improvements. The role of local institutions as a stimulant and a reflection of the CBD (Community Base Development) with a group of people who will have a sense of community are good, such as the ability to take care of its interests in a responsible manner, free to choose and express their opinions, actively participate in the common interest, and community services closer to the interests of society itself. -

Supreme Court Minutes Wednesday, March 28, 2018 San Francisco, California

454 SUPREME COURT MINUTES WEDNESDAY, MARCH 28, 2018 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA S246255 STEWART (DYLAN) v. SAN LUIS AMBULANCE, INC. Request for certification granted The court grants the request, made pursuant to California Rules of Court, rule 8.548, that this court decide a question of California law presented in a matter pending in the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. For purpose of briefing and oral argument, appellant Dylan Stewart is deemed the petitioner in this court. (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.520(a)(6).) Votes: Cantil-Sakauye, C. J., Chin, Corrigan, Liu, Cuéllar, and Kruger, JJ. S246911 B278642 Second Appellate District, Div. 4 KIM (JUSTIN) v. REINS INTERNATIONAL CALIFORNIA, INC. Petition for review granted Votes: Cantil-Sakauye, C. J., Chin, Corrigan, Liu, Cuéllar, and Kruger, JJ. S247095 A141913 First Appellate District, Div. 4 ALAMEDA COUNTY DEPUTY SHERIFF’S ASSOCIATION v. ALAMEDA COUNTY EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT ASSN. AND BD. OF THE ALAMEDA COUNTY EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT ASSN.; SERVICE EMPLOYEES INTERNATIONAL UNION, LOCAL 1021; BUILDING TRADES COUNCIL OF ALAMEDA COUNTY Petitions for review granted The request for an order directing depublication of the opinion is denied. Votes: Cantil-Sakauye, C. J., Chin, Corrigan, Liu, Cuéllar, and Kruger, JJ. SAN FRANCISCO MARCH 28, 2018 455 S237460 A139610 First Appellate District, Div. 2 MARIN ASSOCIATION OF PUBLIC EMPLOYEES v. MARIN COUNTY EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT ASSOCIATION; STATE OF CALIFORNIA Order filed: case held pending decision in another case Further action in this matter is deferred pending consideration and disposition of a related issue in Alameda County Deputy Sheriffs’ Assn. v. Alameda County Employees’ Retirement Assn., S247095 (see Cal. -

AGFS Kongress Smarte Pendler

AGFS Kongress Smarte Pendler Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr AöR Essen, 27.2.2020 Michael Zyweck Vernetzte Mobilität / Koordination ÖPNV Wie möchten Sie eine Woche Ihrer Freizeit verbringen ? So…. Bildnachweis: nakedking - stock.adobe.com Seite 2 Michael Zyweck, Essen, AGFS – Kongress 2020, …oder so? Bildnachweis: Tupungato - stock.adobe.com Eine Woche pro Jahr für die Parkplatzsuche in urbanen Räumen Seite 3 Michael Zyweck, Essen, AGFS – Kongress 2020, Ziel: Smarter Umstieg zwischen Verkehrsmitteln Beispiel Radverkehr Seite 4 Michael Zyweck, Essen, AGFS – Kongress 2020, Nötig ist dazu die Investition in sichereres Abstellen an ÖPNV Haltepunkten Quelle: Kienzler Stadtmobiliar GmbH System im VRR: DeinRadschloss-Anlagen unterschiedlicher Betreiber in vielen Städten Seite 5 Michael Zyweck, Essen, AGFS – Kongress 2020, Vom Schlüsselsystem zum digitalen Zugang und Abrechnung Quelle: GRONARD® metallbau & stadtmobiliar gmbh Quelle: Kienzler Stadtmobiliar GmbH Quelle: Kienzler Stadtmobiliar GmbH/VRR Quelle: Bogestra Reservierbar für Tag, Woche, Monat, Jahr Seite 6 Michael Zyweck, Essen, AGFS – Kongress 2020, Rolle und Ziele des VRR bei P+R und B+R . Koordinator für den ÖPNV (Fachliche Unterstützung bei Maßnahmen ) . Bewilligungsbehörde für Maßnahmen . Federführung bei der Maßnahme „Ausbau der Digitalisierung P&R in NRW - mobil.nrw “ (ÖPNV Digitalisierungsoffensive NRW) Ziel 1: Regionale Vernetzung der P+R Strategien Ziel 2: Erhöhung Ausstattung und Qualität von P+R-Anlagen Ziel 3: Digitalisierung des P+R („Smarte Pendlerparkplätze“) Seite 7 Michael Zyweck, Essen, AGFS – Kongress 2020, Ziel 1: Regionale Vernetzung des P+R. Lokal und regional handeln! Stadt Düsseldorf ca. 313.000 Einpendler pro Tag = ca. 183.000 Pkw im Berufsverkehr ca. 1.000 P+R-Stellplätze an SPNV- Stationen in der Stadt Bedarf Angebot Seite 8 Michael Zyweck, Essen, AGFS – Kongress 2020, Ziel 1: Regionale Vernetzung des P+R. -

Budapester Altbauquartiere Im Revitalisierungsprozess Kovács, Zoltán; Wiessner, Reinhard; Zischner, Romy

www.ssoar.info Budapester Altbauquartiere im Revitalisierungsprozess Kovács, Zoltán; Wiessner, Reinhard; Zischner, Romy Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kovács, Z., Wiessner, R., & Zischner, R. (2007). Budapester Altbauquartiere im Revitalisierungsprozess. Europa Regional, 15.2007(3), 153-165. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-48056-8 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner -

Antwort Der Bundesregierung

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/10780 18. Wahlperiode 28.12.2016 Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Niema Movassat, Annette Groth, Heike Hänsel, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. – Drucksache 18/10619 – Kooperation der Bundesregierung mit privaten Stiftungen am Beispiel der Bill, Hillary and Chelsea Clinton Foundation Vorbemerkung der Fragesteller Anfang November 2016 haben Medienberichte Zahlungen der Bundesregierung an die Clinton Foundation öffentlich gemacht. Im dritten Quartal 2016, also auf der Höhe des Wahlkampfs, flossen deutsche Steuergelder in Höhe von bis zu 5 Mio. US-Dollar vom Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit an die Familienstiftung. Bei dem genannten Betrag handele es sich um „Finanzierungen im Rahmen der Klimaschutzinitiative“ (IKI). Dem- nach dienten die deutschen Steuergelder der „Unterstützung von Forst- und Landschaftsrenaturierung in Ostafrika“. Dieses Projekt werde mit deutscher Ko- finanzierung „unmittelbar von der Clinton Foundation in Kenia und Äthiopien durchgeführt“ (siehe: www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article159791364/Bundesregie- rung-zahlte-Millionen-an-Clinton-Stiftung.html). Dies ist nicht die einzige Finanzierung der Clinton Foundation durch die Bun- desregierung. Wie aus der Antwort auf die Schriftliche Frage 50 auf Bundes- tagsdrucksache 18/10551 des Abgeordneten Niema Movassat vom November 2016 hervorging, stellte zudem die Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zu- sammenarbeit und Entwicklung (GIZ) GmbH im Auftrag des Bundesministeri- ums für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ) der Clinton Development Initiative (DCI) für ein Projekt in Malawi von Juni 2013 bis Mai 2016 bis zu 2,4 Mio. Euro aus dem Haushalt des BMZ über einen Finanzie- rungsvertrag zur Verfügung (siehe: www.clintonfoundation.org/contributors? category=%241%2C000%2C001%20to%20%245%2C000%2C000&page=1). -

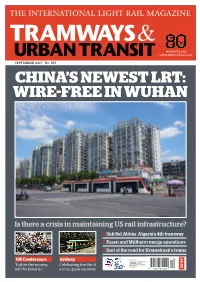

China's Newest

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com SEPTEMBER 2017 NO. 957 CHINA’S NEWEST LRT: WIRE-FREE IN WUHAN Is there a crisis in maintaining US rail infrastructure? Sidi Bel Abbès: Algeria’s 4th tramway Essen and Mülheim merge operations End of the road for Kramatorsk’s trams UK Conference Sydney 09> £4.40 ‘Follow the money, Celebrating the life of sell the benefits’ a once-great tramway 9 771460 832050 4 October 2017 Entries open now! t: +44 (0)1733 367600 @ [email protected] www.lightrailawards.com CONTENTS The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association SEPTEMBER 2017 Vol. 80 No. 957 www.tautonline.com 341 EDITORIAL EDITOR Simon Johnston E-mail: [email protected] 13 Orton Enterprise Centre, Bakewell Road, Peterborough PE2 6XU, UK 324 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Tony Streeter E-mail: [email protected] WORLDWIDE EDITOR Michael Taplin Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. E-mail: [email protected] NEWS EDITOR John Symons 17 Whitmore Avenue, Werrington, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs ST9 0LW, UK. E-mail: [email protected] SENIOR CONTRIBUTOR Neil Pulling WORLDWIDE CONTRIBUTORS 316 Tony Bailey, James Chuang, Paul Nicholson, Richard Felski, Ed Havens, Bill Vigrass, Andrew Moglestue, NEWS 324 S YSTEMS FACTFILE: BOGESTRA 345 Mike Russell, Nikolai Semyonov, Vic Simons, Herbert New tramlines in Sidi Bel Abbès and Neil Pulling explores the Ruhr network that Pence, Alain Senut, Rick Wilson, Thomas Wagner Wuhan; Gold Coast LRT phase two ‘90% uses different light rail configurations to PDTRO UC ION Lanna Blyth complete’; US FTA plan to reduce barriers to cover a variety of urban areas. -

Stadt Witten: Linienübersicht – Entwicklungskonzept

Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis: Fortschreibung Nahverkehrsplan 1 Stadt Witten: Linienübersicht – Entwicklungskonzept Bestand Entwicklungskonzept Verkehrs- Bedienungsangebot Liniennetz- Bedienungsangebot unter- konzept Linie Linienweg Linie Linienweg Anmerkung nehmen HVZ NVZ SVZ HVZ NVZ SVZ SPNV RE 4 Dortmund – Witten – Hagen – T60 T60 T60 RE 4 Dortmund – Witten – Wetter – Ebene 0 T60 T60 T60 zusätzlicher Halt in Wetter Bf. wird DB Regio Ennepetal – Schwelm – Hagen – Ennepetal – Schwelm – angestrebt NRW Wuppertal – Düsseldorf – Wuppertal – Düsseldorf – Neuss GmbH Neuss – Mönchengladbach – – Mönchengladbach – Aachen Aachen RE 16 Essen – Bochum – Witten – T60 T60 T60 RE 16 Essen – Bochum – Witten – Ebene 0 T60 T60 T60 keine Änderungen ABELLIO Wetter – Hagen – Wetter – Hagen – Hohenlimburg Rail NRW Hohenlimburg (– Siegen) (– Siegen) GmbH RB 40 Essen – Bochum – Witten – T60 T60 T60 RB 40 Essen – Bochum – Witten – Ebene 0 T60 T60 T60 keine Änderungen DB Regio Wetter – Hagen Wetter – Hagen NRW GmbH Ruhr- Bochum-Dahlhausen – 3 Fahrtenpaare (Freitag, Ruhr- Bochum-Dahlhausen – Hattingen Ebene 0 3 Fahrtenpaare (Freitag, keine Änderungen Ruhrtal- tal- Hattingen – Herbede – Witten- Sonn- und Feiertag im tal- – Herbede – Witten-Bommern – Sonn- und Feiertag im Bahn bahn Bommern – Wetter-Wengern – Sommerhalbjahr) bahn Wetter-Wengern – Hagen- Sommerhalbjahr) Betriebs- Hagen-Vorhalle – Hagen Hbf. Vorhalle – Hagen Hbf. gesellschaft mbH S 5 Dortmund – Witten – Wetter – T20/ T20/ T60 S 5 Dortmund – Witten – Wetter – Ebene 0 T30 T30 T60 zu prüfen ist die Umstellung auf einen DB Regio Hagen T40 T40 Hagen durchgehenden 30-Min-Takt NRW GmbH Planungsgruppe Nord Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis: Fortschreibung Nahverkehrsplan 2 Bestand Entwicklungskonzept Verkehrs- Bedienungsangebot Liniennetz- Bedienungsangebot unter- konzept Linie Linienweg Linie Linienweg Anmerkung nehmen HVZ NVZ SVZ HVZ NVZ SVZ Straßenbahn 310 Bochum-WAT-Höntrop – T20 T20 T30 310 Bochum-WAT-Höntrop – BO Hbf. -

Thematic Evaluation of the Territorial Employment Pacts

Thematic Evaluation of the Territorial Employment Pacts Final Report to Directorate General Regional Policy ANNEX III : NATIONAL AND CASE STUDY REPORTS OCTOBER 2002 by ECOTEC Research & Consulting Limited 13B Avenue de Tervuren B-1040 Brussels BELGIUM Tel: +32 (02) 743 89 49 Fax: +32 (02) 732 71 11 Ecotec Research and Consulting Ltd Thematic Evaluation of the Territorial Employment Pacts Final Report to Directorate General Regional Policy ANNEX III : NATIONAL AND CASE STUDY REPORTS October 2002 ECOTEC Research and Consulting Limited 13b Avenue de Tervuren Priestley House B-1040 Brussels 28-34 Albert Street Belgium Birmingham B4 7UD Tel: +32 (0)2 743 8949 United Kingdom Fax: +32 (0)2 743 7111 Tel: +44 (0)121 616 3600 Fax: +44 (0)121 616 3699 Web: www.ecotec.com E-mail: [email protected] Modesto Lafuente 63 – 6a E-28003 Madrid Spain Tel: +34 91 535 0640 Fax: +34 91 533 3663 6-8 Marshalsea Road London SE1 1HL United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7089 5550 Fax: +44 (0)20 7089 5559 31-32 Park Row Leeds LS1 5JD United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)113 244 9845 Fax: +44 (0)113 244 9844 Ecotec Research and Consulting Ltd COUNTRY REPORTS AND CASE STUDIES BY ECOTEC’S NATIONAL CORRESPONDENTS CONTENT BELGIUM: TEP Programme as a whole 3 • TEP Halle-Vilvoorde 14 • TEP Bruxelles-Capitale 25 DENMARK: TEP Programme as a whole 34 • TEP Viborg 38 GERMANY: TEP Programme as a whole 46 • TEP Berlin-Neukölln 55 • TEP North-Rhine-Westphalia 74 • TEP Chemnitz 90 GREECE: TEP Programme as a whole 113 • TEP Imathia 120 • TEP Magnesia 125 SPAIN: TEP Programme as a whole 130 • TEP