A Look at the Public Sphere in Talk Show Programs in Albania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albanian Media and the Specifics of the Local Market

Studies in Communication Sciences 12 (2012) 49–52 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Studies in Communication Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scoms General section Albanian media and the specifics of the local market Mark Marku 1 Department of Journalism and Communication, University of Tirana, Albania article info abstract Keywords: After the fall of communism in 1991, Albanian media rode a wave of privatization, bringing with it a load Albanian media of new market entrants and a high level of disorder. As the media market began to grow and private Media diversity outlets captured larger audiences, holes appeared in Albanian media legislation, making it difficult to Media competition enforce fiscal transparency and competition amongst participants. Privatized media As a result of their market advantage, large private media companies are now outspending smaller competitors in order to boost innovation and technology. As media companies continue to grow in all major forms of Albanian media, large stations exploit the lack of government oversight to increase their advantage in advertising, programming, and technological innovation. By implementing legislation designed to stabilize growth, the diversity of Albanian media outlets will increase along with widespread advancements to technology and infrastructure. © 2012 Swiss Association of Communication and Media Research. Published by Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved. Changes to the political system in Albania are associated with the Albanian-speaking media scene. According to statistics from the the evolution and radical transformation of the media field. The National Council of Radio and Television KKRT (KKRT 2011, p. 34) establishment of both political pluralism and a market economy in in Albania today, four national television stations are in operation, 1991 brought with it the collapse of the state’s monopoly over the 65 local stations, 33 cable television stations, three national and 47 Albanian media market. -

TV and On-Demand Audiovisual Services in Albania Table of Contents

TV and on-demand audiovisual services in Albania Table of Contents Description of the audiovisual market.......................................................................................... 2 Licensing authorities / Registers...................................................................................................2 Population and household equipment.......................................................................................... 2 TV channels available in the country........................................................................................... 3 TV channels established in the country..................................................................................... 10 On-demand audiovisual services available in the country......................................................... 14 On-demand audiovisual services established in the country..................................................... 15 Operators (all types of companies)............................................................................................ 15 Description of the audiovisual market The Albanian public service broadcaster, RTSH, operates a range of channels: TVSH (Shqiptar TV1) TVSH 2 (Shqiptar TV2) and TVSH Sat; and in addition a HD channel RTSH HD, and three thematic channels on music, sport and art. There are two major private operators, TV Klan and Top Channel (Top Media Group). The activity of private electronic media began without a legal framework in 1995, with the launch of the unlicensed channel Shijak TV. After -

Freedom of the Press - Albania (2011)

Page 1 of 2 Print Freedom Of The Press - Albania (2011) Status: Partly Free Legal Environment: 16 Political Environment: 17 Economic Environment: 17 Total Score: 50 The constitution guarantees freedom of the press, and the media are vigorous and fairly diverse. However, outlets often display a strong political bias, and their reporting is influenced by the economic or political interests of their owners. Libel remains a criminal offense, punishable by fines and up to two years in prison. While there have been no criminal libel cases against journalists in recent years, former culture minister Ylli Pango successfully sued the private television station Top Channel for airing hidden- camera video of him asking young female job applicants to disrobe. He had been forced to resign after the recordings were broadcast in March 2009. In June 2010, a court ordered the station to pay roughly $500,000 in damages to Pango on the grounds that they had been obtained illegally. The government of Prime Minister Sali Berisha has repeatedly used administrative mechanisms, including tax investigations and arbitrary evictions from state-owned buildings, to disrupt the operations of media outlets it perceives as hostile. Regulatory bodies are seen as highly politicized. Journalists sometimes face intimidation and assaults in response to critical reporting. Mero Baze, the owner of the newspaper Tema and host of a talk show on the independent television station Vizion Plus, was allegedly assaulted by businessman Rezart Taci and two of his bodyguards in November 2009. Through his media outlets, Baze had accused Taci of tax evasion and irregularities in his acquisition of a state-owned oil refinery. -

People's Advocate… ………… … 291

REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE ANNUAL REPORT On the activity of the People’s Advocate 1st January – 31stDecember 2013 Tirana, February 2014 REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA ANNUAL REPORT On the activity of the People’s Advocate 1st January – 31st December 2013 Tirana, February 2014 On the Activity of People’s Advocate ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Honorable Mr. Speaker of the Assembly of the Republic of Albania, Honorable Members of the Assembly, Ne mbeshtetje te nenit 63, paragrafi 1 i Kushtetutes se republikes se Shqiperise dhe nenit26 te Ligjit N0.8454, te Avokatit te Popullit, date 04.02.1999 i ndryshuar me ligjin Nr. 8600, date10.04.200 dhe Ligjit nr. 9398, date 12.05.2005, Kam nderin qe ne emer te Institucionit te Avokatit te Popullit, tj’u paraqes Raportin per veprimtarine e Avokatit te Popullit gjate vitit 2013. Pursuant “ to Article 63, paragraph 1 of the Constitution of the Republic of Albania and Article 26 of Law No. 8454, dated 04.02.1999 “On People’s Advocate”, as amended by Law No. 8600, dated 10.04.2000 and Law No. 9398, dated 12.05.2005, I have the honor, on behalf of the People's Advocate Institution, to submit this report on the activity of People's Advocate for 2013. On the Activity of People’s Advocate Sincerely, PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE Igli TOTOZANI ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Table of Content Prezantim i Raportit Vjetor 2013 8 kreu I: 1Opinione dhe rekomandime mbi situaten e te drejtave te njeriut ne Shqiperi …9 2) permbledhje e Raporteve te vecanta drejtuar Parlamentit te Republikes se Shqiperise......................... -

A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground

Media Programme SEE A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground Public Service Media in South East Europe RECONNECTING WITH DATA CITIZENS TO BIG VALUES – FROM A Pillar of Democracy of Shaky on Ground A Pillar www.kas.de www.kas.dewww.kas.de Media Programme SEE A Pillar of Democracy on Shaky Ground Public Service Media in South East Europe www.kas.de Imprint Copyright © 2019 by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Media Programme South East Europe Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Authors Viktorija Car, Nadine Gogu, Liana Ionescu, Ilda Londo, Driton Qeriqi, Miroljub Radojković, Nataša Ružić, Dragan Sekulovski, Orlin Spassov, Romina Surugiu, Lejla Turčilo, Daphne Wolter Editors Darija Fabijanić, Hendrik Sittig Proofreading Boryana Desheva, Louisa Spencer Translation (Bulgarian, German, Montenegrin) Boryana Desheva, KERN AG, Tanja Luburić Opinion Poll Ipsos (Ivica Sokolovski), KAS Media Programme South East Europe (Darija Fabijanić) Layout and Design Velin Saramov Cover Illustration Dineta Saramova ISBN 978-3-95721-596-3 Disclaimer All rights reserved. Requests for review copies and other enquiries concerning this publication are to be sent to the publisher. The responsibility for facts, opinions and cross references to external sources in this publication rests exclusively with the contributors and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Table of Content Preface v Public Service Media and Its Future: Legitimacy in the Digital Age (the German case) 1 Survey on the Perception of Public Service -

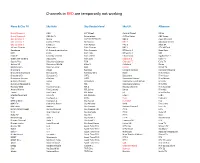

Channels in RED Are Temporarily Not Working

Channels in RED are temporarily not working Nova & Ote TV Sky Italy Sky Deutschland Sky UK Albanian Nova Cinema 1 AXN 13th Street Animal Planet 3 Plus Nova Cinema 2 AXN SciFi Boomerang At The Races ABC News Ote Cinema 1 Boing Cartoon Network BBC 1 Agon Channel Ote Cinema 2 Caccia e Pesca Discovery BBC 2 Albanian screen Ote Cinema 3 Canale 5 Film Action BBC 3 Alsat M Village Cinema Cartoonito Film Cinema BBC 4 ATV HDTurk Sundance CI Crime Investigation Film Comedy BT Sports 1 Bang Bang FOX Cielo Film Hits BT Sports 2 BBF FOXlife Comedy Central Film Select CBS Drama Big Brother 1 Greek VIP Cinema Discovery Film Star Channel 5 Club TV Sports Plus Discovery Science FOX Chelsea FC Cufo TV Action 24 Discovery World Kabel 1 Clubland Doma Motorvision Disney Junior Kika Colors Elrodi TV Discovery Dmax Nat Geo Comedy Central Explorer Shkence Discovery Showcase Eurosport 1 Nat Geo Wild Dave Film Aktion Discovery ID Eurosport 2 ORF1 Discovery Film Autor Discovery Science eXplora ORF2 Discovery History Film Drame History Channel Focus ProSieben Discovery Investigation Film Dy National Geographic Fox RTL Discovery Science Film Hits NatGeo Wild Fox Animation RTL 2 Disney Channel Film Komedi Animal Planet Fox Comedy RTL Crime Dmax Film Nje Travel Fox Crime RTL Nitro E4 Film Thriller E! Entertainment Fox Life RTL Passion Film 4 Folk+ TLC Fox Sport 1 SAT 1 Five Folklorit MTV Greece Fox Sport 2 Sky Action Five USA Fox MAD TV Gambero Rosso Sky Atlantic Gold Fox Crime MAD Hits History Sky Cinema History Channel Fox Life NOVA MAD Greekz Horror Channel Sky -

Media Në Tranzicion: Reflektim Pas Tri Dekadash Media Në Tranzicion: Refleksione Pas Tri Dekadash

MEDIA NË TRANZICION: reflektim pas tri dekadash MEDIA NË TRANZICION: REFLEKSIONE PAS TRI DEKADASH Tiranë, 2020 Media në Tranzicion: refleksione pas tri dekadash 1 Botues: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Office Tirana Rr. Kajo Karafili Nd-14, Hyrja 2, Kati 1, Kutia Postare 1418 Tiranë, Shqipëri Për realizimin e këtij studimi punoi një grup pune i përbërë nga Agim Doksani, Dorentina Hysa, Kejsi Bozo. Kopertina dhe layout: Bujar Karoshi Opinionet, gjetjet, konkluzionet dhe rekomandimet e shprehura në këtë botim janë të autorëve dhe nuk reflektojnë domosdoshmërisht ato të Fondacionit Friedrich Ebert. Publikimet e Fondacionit Friedrich Ebert nuk mund të përdoren për arsye komerciale pa miratim me shkrim. 2 Media në Tranzicion: refleksione pas tri dekadash Përmbajtja e lëndës KAPITULLI 1 30 VJET MEDIA NË TRANZICION: NJË PANORAMË HISTORIKE .................................................................................... 5 KAPITULLI 2 RRUGA E VËSHTIRË DREJT LIRISË SË MEDIAS ............................................ 29 KAPITULLI 3 SFIDAT E PROFESIONALIZMIT: MEDIA NDËRMJET BIZNESIT DHE POLITIKËS ...................................................................................... 45 Referenca ........................................................................................................................ 55 Media në Tranzicion: refleksione pas tri dekadash 3 4 Media në Tranzicion: refleksione pas tri dekadash KAPITULLI 1 30 VJET MEDIA NË TRANZICION: NJË PANORAMË HISTORIKE I. SHTYPI I SHKRUAR: NJË RRUGË ME KTHESA Një parahistori Pas një periudhe -

Lista E TV Kanaleve

Lista e TV Kanaleve Pako bazë 1 TVM Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 2 TVM 2 Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 3 TVM 3 Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 4 TVM 4 Sportiv Pako bazë HD 5 TVM 5 Fëmijë Pako bazë HD 6 Sitel Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 7 Telma Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 8 24 Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 9 Kanal 5 Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 10 KLAN MACEDONIA Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 11 Alfa TV Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 12 TV Sonce Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 13 ALSAT Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 14 SHENJA Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 15 Nasha TV Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 16 TVM Kuvendor Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 17 EDO Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 18 21TV Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë HD 19 KOHA Kolazh (МКД) Pako bazë SD 20 Balkan Music Muzikor Pako bazë SD 21 ARTE Dokumentar Pako bazë HD 22 Game Toon Argëtues Pako bazë HD 23 Zdrava Televizija Argëtues Pako bazë SD 24 Boomerang Fëmijë Pako bazë SD 25 Cartoon Network Fëmijë Pako bazë SD 26 Jim Jam Fëmijë Pako bazë SD 27 RT Documentary HD Dokumentar Pako bazë HD 28 CNN International Informativ Pako bazë SD 29 Rai UNO Informativ Pako bazë SD 30 Rai DUO Informativ Pako bazë SD 31 TVE Informativ Pako bazë HD 32 TRT 1 Informativ Pako bazë HD 33 SAT 1 Informativ Pako bazë SD 34 RTR PLANETA Informativ Pako bazë SD 35 Russia Today Informativ Pako bazë HD 36 Russia 24 Informativ Pako bazë SD 37 RTL Informativ Pako bazë SD 38 HRT 1 Kolazh (Regjional) Pako bazë HD НЕОТЕЛ ДОО Скопје; Кузман Јосифовски Питу бр.15, 1000 Скопје, Република Северна Македонија Тел:+389 2 55 11 155; Техничка поддршка: +389 2 55 11 111 www.neotel.mk 39 HRT 3 -

New News, Future News the Challenges for Television News After Digital Switch-Over

New News, Future News The challenges for television news after Digital Switch-over An Ofcom discussion document Publication date: 26 June 2007 Foreword The prospects for television news in a fully digital era are a central element in any consideration of the future of public service broadcasting (PSB). News is regarded by viewers as the most important of all the PSB genres, and television remains by far the most used source of news for UK citizens. The role of news and information as part of the democratic process is long established, and its status is specifically underpinned in the Communications Act 2003. This report, New News, Future News, is one of a series of Ofcom studies focussing on individual topics identified in the PSB Review of 2004/05, and further discussed in the Digital PSB report of July 2006. The others are on the provision of children’s programmes and on the prospects for a Public Service Publisher. All three studies are linked to areas of particular PSB concern for the future, and set out a framework for policy consideration ahead of the next full PSB review. Other Ofcom work of relevance includes the review of Channel 4’s funding. It has not been the role of this report to come up with solutions, and no policy recommendations are put forward. Instead, the report examines the environment in which television news currently operates, and assesses how that may change in future (after digital switch-over and, in 2014, the expiry of current Channel 3 and Channel 5 licences) . It identifies particular issues that will need to be addressed and suggests some specific questions that may need to be answered. -

ALBANIA Country Report

Footprint of Financial Crisis in the Media ALBANIA country report Compiled by Thanas Goga Commissioned by Open Society Institute December 2009 FOOTPRINT OF FINANCIAL CRISIS IN THE MEDIA Economy 2009 was a year of economic and financial uncertainty the world over. While the economic situation in Albania is not as dismal as in some of the other neighboring countries (the economy is still experiencing positive growth), the general market sentiment continues to be negative. This is in partly due to the free-floating exchange rate of the Albanian currency, the lek (ALL), which has declined against the euro by 7–8 per cent over the past 12 months, although local customers have reportedly withdrawn about 10 per cent of consumer deposits accounts from commercial retail banks amid fears that the global crisis would engulf the country’s small economy. Additionally, Albanian migrants’ remittances, which account for almost a quarter of the country’s GDP, fell reportedly by 6.2 per cent in the first six months of 2009 to € 420 million, reflecting the tougher conditions for migrants working abroad. Inflows of foreign direct investment doubled in the first half of the year to € 460 million, but the bulk of funds came from privatisation deals negotiated before the global crisis, such as CEZ, the Czech energy company that paid € 102 million for OSSH, Albania’s only electricity distributor, or other deals, including the sale of ARMO, the state-owned oil refinery, to local investors, and the sale of a residual stake in AMC, a leading mobile telephony operator, to its majority shareholder, Cosmote of Greece. -

Albanian Media Institute, “Children and the Media: a Survey of the Children and Young People’S Opinion on Their Use and Trust in Media,” December 2011, P

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: ALBANIA Mapping Digital Media: Albania A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Ilda Londo (reporter) EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 20 January 2012 Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 11 Economic Indicators ......................................................................................................................... 12 1. Media Consumption: Th e Digital Factor ......................................................................... -

ALBANIA Ilda Londo

ALBANIA Ilda Londo porocilo.indb 51 20.5.2014 9:04:36 INTRODUCTION Policies on media development have ranged from over-regulation to complete liberali- sation. Media legislation has changed frequently, mainly in response to the developments and emergence of media actors on the ground, rather than as a result of a deliberate and carefully thought-out vision and strategy. Th e implementation of the legislation was ham- pered by political struggles, weak rule of law and interplays of various interests, but some- times the reason was the incompetence of the regulatory bodies themselves. Th e Albanian media market is small, but the media landscape is thriving, with high number of media outlets surviving. Th e media market suff ers from severe lack of trans- parency. It also seems that diversifi cation of sources of revenues is not satisfactory. Media are increasingly dependent on corporate advertising, on the funds arising from other busi- nesses of their owners, and to some extent, on state advertising. In this context, the price of survival is a loss of independence and direct or indirect infl uence on media content. Th e lack of transparency in media ratings, advertising practices, and business practices in gen- eral seems to facilitate even more the infl uences on media content exerted by other actors. In this context, the chances of achieving quality and public-oriented journalism are slim. Th e absence of a strong public broadcaster does not help either. Th is research report will seek to analyze the main aspects of the media system and the way they aff ect media integrity.