POEMS of THOMAS HARDY a New Selection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Hardy

Published on Great Writers Inspire (http://writersinspire.org) Home > Thomas Hardy Thomas Hardy Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), novelist and poet, was born on 2 June 1840, in Higher Bockhampton, Dorset. The eldest child of Thomas Hardy and Jemima Hand, Hardy had three younger siblings: Mary, Henry, and Katharine. Hardy learned to read at a very young age, and developed a fascination with the services he regular attended at Stinsford church. He also grew to love the music that accompanied church ritual. His father had once been a member of the Stinsford church musicians - the group Hardy later memorialised in Under the Greenwood Tree - and taught him to play the violin, with the pair occasionally performing together at local dance parties. Whilst attending the church services, Hardy developed a fascination for a skull which formed part of the Grey family monument. He memorised the accompanying inscription (containing the name 'Angel', which he would later use in his novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles [1]) so intently that he was still able to recite it well into old age. [2] Thomas Hardy By Bain News Service [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Adulthood Between the years of 1856-1862, Hardy worked as a trainee architect. He formed an important friendship with Horace Moule. Moule - eight years Hardy's senior and a Cambridge graduate - became Hardy's intellectual mentor. Horace Moule appears to have suffered from depression, and he committed suicide in 1873. Several of Hardy's poems are dedicated to him, and it is thought some of the characters in Hardy's fiction were likely to have been modeled on Moule. -

Prelims- 1..26

THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO THOMAS HARDY EDITED BY DALE KRAMER published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb21rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, United Kingdom http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia # Cambridge University Press 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Sabon 10/13 pt. [ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data The Cambridge companion to Thomas Hardy / edited by Dale Kramer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 56202 3 ± isbn 0 521 56692 4 (paperback) 1. Hardy, Thomas, 1840±1928 ± Criticism and interpretation. I. Kramer, Dale, 1936± . pr4754.c23 1999 823'.8±dc21 98±38088 cip isbn 0 521 56202 3 hardback isbn 0 521 56692 4 paperback CONTENTS Notes on contributors page xi Preface xv A chronology of Hardy's life and Publications xviii List of abbreviations and texts xxiii 1 Thomas Hardy: the biographical sources 1 MICHAEL MILLGATE 2 Wessex 19 SIMON GATRELL 3 Art and aesthetics 38 NORMAN PAGE 4 The in¯uence of religion, science, and philosophy on Hardy's writings 54 ROBERT SCHWEIK 5 Hardy and critical theory 73 PETER WIDDOWSON 6 Thomas Hardy and matters of gender 93 KRISTIN BRADY 7 Variants on genre: The Return of the Native, The Mayor of Casterbridge, The Hand of Ethelberta 112 JAKOB LOTHE 8 The patriarchy of class: Under the Greenwood Tree, Far from the Madding Crowd, The Woodlanders 130 PENNY BOUMELHA ix contents 9 The radical aesthetic of Tess of the d'Urbervilles 145 LINDA M. -

A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY

A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY By the same author THE MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE (Macmillan Critical Commentaries) A HARDY COMPANION ONE RARE FAIR WOMAN Thomas Hardy's Letters to Florence Henniker, 1893-1922 (edited, with Evelyn Hardy) A JANE AUSTEN COMPANION A BRONTE COMPANION THOMAS HARDY AND THE MODERN WORLD (edited,for the Thomas Hardy Society) A Commentary on the Poems of THOMAS HARDY F. B. Pinion ISBN 978-1-349-02511-4 ISBN 978-1-349-02509-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-02509-1 © F. B. Pinion 1976 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 15t edition 1976 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1976 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Associated companies in New York Dublin Melbourne Johannesburg and Madras SBN 333 17918 8 This book is sold subject to the standard conditions of the Net Book Agreement Quid quod idem in poesi quoque eo evaslt ut hoc solo scribendi genere ..• immortalem famam assequi possit? From A. D. Godley's public oration at Oxford in I920 when the degree of Doctor of Letters was conferred on Thomas Hardy: 'Why now, is not the excellence of his poems such that, by this type of writing alone, he can achieve immortal fame ...? (The Life of Thomas Hardy, 397-8) 'The Temporary the AU' (Hardy's design for the sundial at Max Gate) Contents List of Drawings and Maps IX List of Plates X Preface xi Reference Abbreviations xiv Chronology xvi COMMENTS AND NOTES I Wessex Poems (1898) 3 2 Poems of the Past and the Present (1901) 29 War Poems 30 Poems of Pilgrimage 34 Miscellaneous Poems 38 Imitations, etc. -

Emma Hardy's Late Writings Restored Jon Singleton Harding University, [email protected]

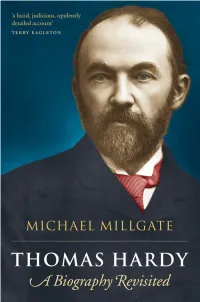

Harding University Scholar Works at Harding English Faculty Research and Publications English Fall 2015 Spaces, Alleys, and Other Lacunae: Emma Hardy's Late Writings Restored Jon Singleton Harding University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/english-facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Singleton, J. (2015). Spaces, Alleys, and Other Lacunae: Emma Hardy's Late Writings Restored. Thomas Hardy Journal, 31, 48-62. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.harding.edu/english-facpub/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Scholar Works at Harding. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Research and Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at Harding. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPACES, ALLEYS, AND OTHER LACUNAE: EMMA HARDY’S LATE WRITINGS RESTORED JON SINGLETON Emma Hardy’s writings have often been misrepresented by Hardy scholars as naïve, incoherent, or insane. Her case has not been helped by the fact that Thomas Hardy, along with his second wife Florence Dugdale, burned reams of Emma’s papers in the months and years following her death. But the most blatant misrepresentation has been the actual corruption of the text of Spaces (1912), her last published work. Two full pages – the recto and verso of the same leaf – were left out when J. O. Bailey and J. Stevens Cox republished it in 1966, along with Emma’s Alleys (1911), under the title Poems and Religious Effusions. All subsequent scholarship, from Michael Millgate’s magisterial Biography Revisited on down, has relied upon this corrupted version to assess Emma’s literary merits and even to diagnose her mental health. -

Life and Biography of Hardy

IASET: Journal of Linguistics and Literature (IASET: JLL) ISSN(P): Applied; ISSN(E): Applied Vol. 1, Issue 1, Jan - Jun 2016, 11-16 © IASET LIFE AND BIOAGRPHY OF THOMAS HARDY M. ASHA Assistant Professor, Department of English, Hosur Institute of Technology and Science, Tamil Nadu, India. ABSTRACT The topic has taken up for the study of the life and biography of Thomas Hardy and which made him to analyze the emerging self-conscious women. KEYWORDS: Feminism, Self-Conscious, Women INTRODUCTION It deals with the life and biographical sketch of Thomas Hardy. It gives an introductory note on feminism, interpreting the thematic concerns. It is really ironic to note that it was the male British writer who were experimented in exposing the patriarchal prejudice of our culture, following him feminist critics have subjected the novels of the old writers, where the heroines suffer the pressure of patriarchy. As a weaker sex of the class how their psychological prospect is portrayed in the social is clear scrutinized by the writer. Though the writer belong to the Patriarchal Society portrays the emergences of women. To study in detail is the aim of this topic. Life of Thomas Hardy Hardy was born on June 2, in 1840 to Thomas and Jemima Hardy at Higher Bockhampton, Dorset. His father was a mason master and builder. Hardy gained an appreciation of music from his father and from his mother, an appetite for learning the delights of the countryside about his rural home. In 1848, at the age of eight though he was delicate Hardy entered his first school at the Stinsford Parish, where he learned Mathematics and Geography. -

Tess of the D'urbervilles

oxford world’ s classics TESS OF THE D’URBERVILLES Thomas Hardy was born in Higher Bockhampton, Dorset, on 2 June 1840; his father was a builder in a small way of business, and he was educated locally and in Dorchester before being articled to an architect. After sixteen years in that profession and the publica- tion of his earliest novel Desperate Remedies (1871), he determined to make his career in literature; not, however, before his work as an architect had led to his meeting, at St Juliot in Cornwall, Emma Gifford, who became his first wife in 1874. In the 1860s Hardy had written a substantial amount of unpublished verse, but during the next twenty years almost all his creative effort went into novels and short stories. Jude the Obscure, the last written of his novels, came out in 1895, closing a sequence of fiction that includes Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), The Return of the Native (1878), Two on a Tower (1882), The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), and Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891). Hardy maintained in later life that only in poetry could he truly express his ideas; and the more than nine hundred poems in his collected verse (almost all published after 1898) possess great individuality and power. In 1910 Hardy was awarded the Order of Merit; in 1912 Emma died and two years later he married Florence Dugdale. Thomas Hardy died in January 1928; the work he left behind––the novels, the poetry, and the epic drama The Dynasts––forms one of the supreme achievements in English imaginative literature. -

Thomas-Hardy-A-Biography-Revisited-Pdfdrivecom-45251581745719.Pdf

THOMAS HARDY This page intentionally left blank THOMAS HARDY MICHAEL MILLGATE 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 2 6 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Michael Millgate 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 First published in paperback 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data applied for Typeset by Regent Typesetting, London Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Antony Rowe, Chippenham ISBN 0–19–927565–3 978–0–19–927565–6 ISBN 0–19–927566–1 (Pbk.) 978–0–19–927566–3 (Pbk.) 13579108642 To R.L.P. -

The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6Th Edition

H Habbakkuk Hilding, the name given to *Fielding in a in this century it has been much imitated in Western scurrilous pamphlet of 1752, possibly by *Smollett. literature. HABINGTON, William (1605-54), of an old Catholic Hajji Baba of Ispahan, The Adventures of, see family, educated at St Omer and Paris. He married Lucy MORIER. Herbert, daughter of the first Baron Powis, and cele HAKLUYT (pron. Haklit), Richard (1552-1616), of a brated her in Castara (1634, anon.), a collection of love Herefordshire family, educated at Westminster and poems. A later edition (1635) contained in addition Christ Church, Oxford. He was chaplain to Sir Edward some elegies on a friend, and the edition of 1640 a Stafford, ambassador at Paris, 1583-8. Here he learnt number of sacred poems. He also wrote a tragicomedy, much of the maritime enterprises of other nations, and The Queene ofArragon (1640). His poems were edited found that the English were reputed for 'their sluggish by Kenneth Allott (1948), with a life. security'. He accordingly decided to devote himself to HAFIZ, Shams ud-din Muhammad (d. c.1390), a fam collecting and publishing the accounts of English ous Persian poet and philosopher, born at Shiraz, explorations, and to this purpose he gave the remain whose poems sing of love and flowers and wine and der of his life. He had already been amassing material, nightingales. His principal work is the Divan, a col for in 1582 he published Divers Voyages Touching the lection of short lyrics called ghazals, or ghasels, in Discoverie of America. In 1587 he published in Paris a which some commentators see a mystical meaning. -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY And Yet to Every Bad There is a Worse: Tragic Themes in Selected Novels of Thomas Hardy Diplomová Práce Autor: Bc. Tringa Gjurgjeala Vedoucí práce: Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou prací na téma “And Yet to Every Bad There is a Worse: Tragic Themes in Selected Novels of Thomas Hardy” vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne ……………… Podpis……………. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph. D. for his support, his patience and motivation. I take this opportunity to express gratitude to all of the Department faculty members, especially Ing. Kamila Večeřová, for their help and support. I also thank my family for encouragement, support and consideration. Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………6 1. Thomas Hardy’s Biography……………………………………………….8 2. Historical Background……………………………………………………15 3. Society and Class Issues in Hardy’s Selected Novels………………… 23 3.1 Social Class Issues in Tess of the D’Urbervilles……………………24 3.2 Social Class Issues in Jude the Obscure…………………………….26 3.3 Social Class Issues in The Return of the Native……………………..29 4. Hardy and Marriage……………………………………………………....31 4.1. Marriage in Tess of the D’Urbervilles……………………………....31 4.2. Marriage in Jude the Obscure……………………………………... 33 4.3. Marriage in The Return of the Native……………………………… 35 5. Hardy and Divorce……………………………………………………… 37 5.1. Divorce in Tess of the D’Urbervilles……………………………… 38 5.2. Divorce in Jude the Obscure………………………………………. 39 5.3. -

FAR from the MADDING CROWD Education Pack

FAR FROM THE MADDING CROWD Education Pack Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 Thomas Hardy ................................................................................................................... 4 Synopsis............................................................................................................................. 5 Hardy and Censorship ....................................................................................................... 6 Rehearsal Diaries .............................................................................................................. 9 Hardy and the Defence of Rural Life ............................................................................... 11 A Visit to Sheepdrove Farm ............................................................................................ 13 A Victorian Agricultural Year ........................................................................................... 14 The Far From The Madding Crowd Timeline .................................................................. 16 The Design Process ......................................................................................................... 21 Credits ............................................................................................................................. 24 This Education Pack was compiled by Beth Flintoff, with contributions from Danielle Pearson, Rosie English and -

A THOMAS HARDY DICTIONARY by the Same Author

A THOMAS HARDY DICTIONARY By the same author ONE RARE FAIR WOMAN Thomas Hardy's letters to Florence Henniker, 1893-1922 (edited with Evelyn Hardy) A COMMENTARY ON THE POEMS OF THOMAS HARDY THOMAS HARDY: ART AND THOUGHT Edited for the New Wessex Edition THOMAS HARDY: TWO ON A TOWER THE STORIES OF THOMAS HARDY (3 vols) Edited for the Thomas Hardy Society THOMAS HARDY AND THE MODERN WORLD BUDMOUTH ESSAYS ON THOMAS HARDY THE THOMAS HARDY SOCIETY REVIEW (annual; editor 1975--84) A HARDY COMPANION A JANE AUSTEN COMPANION A BRONTE COMPANION A GEORGE ELIOT COMPANION A GEORGE ELIOT MISCELLANY A D. H. LAWRENCE COMPANION A WORDSWORTH COMPANION A TENNYSON COMPANION AT. S. ELIOT COMPANION A WORDSWORTH CHRONOLOGY THE COLLECTED SONNETS OF CHARLES (TENNYSON) TURNER (edited with M. Pinion) A Thomas Hardy Dictionary with maps and a chronology F. B. PINION M MACMILLAN PRESS © F. B. Pinion 1989 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1989 978-0-333-42873-3 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended), or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 33-4 Alfred Place, London WC1E 7DP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1989 Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world Typeset by Wessex Typesetters (Division of The Eastern Press Ltd) Frome, Somerset British library Cataloguing in Publication Data A Thomas Hardy dictionary. -

From Thomas Hardy

Colby Quarterly Volume 4 Issue 6 May Article 4 May 1956 Forty Years in a Author's Life: A Dozen Letters (1876-1915) from Thomas Hardy Carl J. Weber Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 4, no.6, May 1956, p.108-117 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Weber: Forty Years in a Author's Life: A Dozen Letters (1876-1915) from 108 Colby Library Quarterly their names would be associated in the establishment of the New York Public Library, so McCutcheon, Wilson, and Gaige had no notion that their common interest in Hardy would, one fine day, thanks to the Bullock benefac tion, find appropriate and united memorialization in the Treasure Room of the Colby College Library. FORTY YEARS IN AN AUTHOR'S LIFE A Dozen Letters* (1876-1915) from Thomas Hardy annotated by CARL J. WEBER URING his lifetime Henry Holt, the American pub D lisher, was very proud of the fact that he had been the one to introduce the Wessex Novels to American readers. "I introduced Hardy here," he boasted. He began by pub lishing Hardy's Under the Greenwood Tree in 1873-without Hardy's knowledge or permission-and he therefore had little just ground for complaint when, on June 20, 1875, the New York Times began the publication of a new Hardy novel about which Holt had received no information.