Subjective (Re)Positioning in Musical Improvisation: Analyzing the Work of Five Female Improvisers *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Improvisation in the Baroque Era

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE MUSicAL IMPROVISATION IN THE BAROQUE ERA Lucca, Complesso Monumentale di San Micheletto 19-21 May 2017 CENTRO STUDI OPERA OMNIA LUIGI BOccHERINI www.luigiboccherini.org INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE MUSicAL IMPROVISATION IN THE BAROQUE ERA Organized by CENTRO STUDI OPERA OMNIA LUIGI BOCCHERINI, LUCCA in collaboration with Ad Parnassum. A Journal of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Instrumental Music Lucca, Complesso Monumentale di San Micheletto 19-21 May 2017 ef PROGRAmmE COmmiTTEE SIMONE CIOLFI (Saint Mary’s College, Rome-Notre-Dame, IN) ROBERTO ILLIANO (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini) FULVIA MORABITO (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini) MASSIMILIANO SALA (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini) ROHAN H. STEWART-MACDONALD (Warwickshire, UK) ef KEYNOTE SPEAKERS GUIDO OLIVIERI (University of Texas at Austin, TX) GIOrgIO SANGUINETTI (Università Tor Vergata, Rome) NEAL ZASLAW (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) FRIDAY 19 MAY 10.00-10.40: Registration and Welcome Opening 10.40-10.50 • FULVIA MORABITO (President Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini) Improvisation in Vocal Music 11.00-12.30 (Chair: Simone Ciolfi, Saint Mary’s College, Rome-Notre-Dame, IN) • Valentina anzani (Università di Bologna), Il mito della competizione tra virtuosi: quando Farinelli sfidò Bernacchi (Bologna 1727) • Hama Jino Biglari (Uppsala University), Reapproaching Italian Baroque Singing • antHony Pryer (Goldsmiths College, University of London), Writing the Un-writable: Caccini, Monteverdi and the Freedoms of the Performer ef 13.00 Lunch 15.30-16.30 – Keynote Speaker 1 • giorgio Sanguinetti (Università Tor Vergata, Rome), On the Origin of Partimento: A Recently Discovered Manuscript of Toccate (1695) by Francesco Mancini The Art of Partimento 17.00-18.00 (Chair: Giorgio Sanguinetti, Università Tor Vergata, Roma) Peter m. -

A Non-Idiomatic Improvisation Course for the Undergraduate Music Curriculum DMA Document Presented In

Improvisation Methods: A Non-Idiomatic Improvisation Course for the Undergraduate Music Curriculum D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Colin A. Wood Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Scott A. Jones, Advisor Mr. Shawn Wallace Dr. David Bruenger Dr. Thomas Wells Dr. Michael Rene Torres 1 Copyrighted by Colin A. Wood 2019 2 Abstract National standards in music education from elementary through the university level dictate that students should receive instruction in musical improvisation. However, most university music curricula do not include coursework devoted to the subject. This document first examines the calls for reform in collegiate music education as well as the challenges and barriers to change. Then, a review of literature illuminates motivations for incorporating improvisation in music education, the benefits of improvisation training, research on assessment in improvisation, and methods for teaching improvisation. A comprehensive semester-long course for teaching non-idiomatic improvisation at the undergraduate level to musicians of all instruments and backgrounds follows. The course design, assignments, and activities are all detailed to facilitate potential adoption by collegiate institutions. The document concludes with avenues for further research on the topic. It is the hope of this author that this document inspires the creation and adoption of courses in improvisation at colleges and universities. ii Vita 2010 ……………………….. B.M. Jazz Studies, West Virginia University 2016 ……………………….. M.M. Saxophone Performance, The Ohio State University 2015 to present ……………. -

132 New on Maybe Monday

New on INTAKT RECORDS www.intaktrec.ch One marker of bassist Michael Formanek's creativity and versatility is the range of distinguished musicians of several generations he's worked with. While still a teenager in the 1970s he toured with drummer Tony Williams and saxophonist Joe Henderson. Starting in the '80s he played long stints with Stan Getz, Fred Hersch and Freddie Hubbard. Formanek is also a composer and leader of various bands. One of his principal recording and international touring vehicles has been his acclaimed quartet with Tim Berne, Craig Taborn and Gerald Cleaver. His occasional groups include the 18-piece all-star Ensemble Kolos- sus, roping in many New York improvisers he works with. Currently his primary focus is the Michael Formanek Elusion Quartet with Tony Malaby, Kris Davis, and Ches Smith. In putting together the Elusion Quartet, interpreting his music with these specific musicians, Michael Formanek says he sought “a more direct connection to emotions: mine, theirs and the listener’s.” Hank Shteamer writes in the liner notes: "As one zeroes in on the details of Time Like This, it's clear that this sort of emotional immediacy permeates the album. You hear it in Kris Davis’ flowing, balletic solo on “A Fine Mess”; in Tony Malaby's ululating tenor cries on “The Soul Goodbye”; in Ches Smith’s raucous grooves on “That Was Then”; or the leader’s poised, sinewy lines on “Culture of None.” Elusive? MicHaeL FOrManek Certainly. But as this album proves, under the right conditions, with the eLusiOn QuarTeT right personnel, it’s still out there." Der New Yorker Bassist und Komponist Michael Formanek präsen- TIME LIKE THIS tiert mit seinem Elusion Quartett ein neues, wegweisendes Projekt. -

Talking Heads Musician Biographies: Pauline Oliveros

PERFORMANCE: (Not Just) Talking Heads Musician Biographies: Pauline Oliveros (1932) is an internationally acclaimed composer, performer, humanitarian, and pioneer in American music. For five decades she has explored sound and forged new ground for herself and others. Through improvisation, electronic music, teaching, ritual, and meditation she has created a body of work with such breadth of vision that it profoundly affects those who experience it. Oliveros was born and raised in Houston, Texas to a musical family. In 1985 she started the Pauline Oliveros Foundation, a non- profit organization in New York, to “support all aspects of the creative process for a worldwide community of artists." Currently she serves as Distinguished Research Professor of Music at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., and as Darius Milhaud Composer-in-residence at Mills College in Oakland, Calif. More information is available atwww.deeplistening.org/pauline. Roger Dean is an Australian sound and multimedia artist, and researcher in music computation and cognition. He is a participant in the Canadian SSHRC MCRI project on Improvisation, Community and Social Practice. He has performed in more than 30 countries, and his compositions include computer and chamber music, and commissions for many ensembles. His music is available on more than 30 commercial recordings originating in Australia, UK, US, and in several publications. He is particularly involved in computerinteractive sound and intermedia work. He has published five research books and many articles on improvisation, particularly in music. He is the founder and director of austraLYSIS, the international creative ensemble making sound and intermedia, and also formed the Sonic Communications Research Group at the University of Canberra. -

The Decline of Improvisation in Western Art Music

The Decline of Improvisation in Western Art Music: An Interpretation of Change Author(s): Robin Moore Source: International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, Vol. 23, No. 1, (Jun., 1992), pp. 61-84 Published by: Croatian Musicological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/836956 Accessed: 23/07/2008 16:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=croat. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org R. MOORE,THE DECLINEOF IMPROVISATION...,IRASM 23 (1992)1, 61-84 61 THE DECLINEOF IMPROVISATIONIN WESTERNART MUSIC: AN INTERPRETATIONOF CHANGE ROBINMOORE UDC: 781.65 OriginalScientific Paper University of Texas, Izvorniznanstveni rad AUSTIN, Texas, USA Received:March 28, 1992 Primljeno:28. -

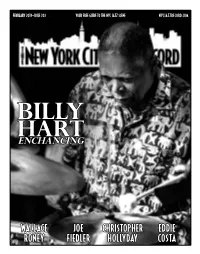

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

Kris Davislooks to Discover the Piano's Full Potential

Outerto the Kris Davis looks to discover the piano’s full potential. ReachesBY TED PANKEN t 7 a.m., 90 minutes before our scheduled morning, after which, Davis told me later, she treated herself interview on Christmas Eve morning, Kris to a rare “day off” that entailed practice, exercise and hanging Davis sent an email: “bad night of sleep — out with her son. call you when I’m up — around 9:30.” We Between our conversations, Davis had pursued her were supposed to speak the previous night, customarily industrious schedule, which included a commute but she emailed me before the appointed from her Ossining, New York, home to Manhattan to teach time to say that a second consecutive day of recording piano and guide the Herbie Hancock Ensemble at the New an orchestral album with saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock at School; a two-hours-each-way drive to teach jazz piano at Manhattan’s Power Station left her too punchy “to do you Princeton; and two long rehearsals with Laubrock. The day much good.” When we finally connected at 9:30 sharp, Davis after our second talk, she led a new trio with Eric Revis and explained that she’d been up most of the night soothing her Johnathan Blake at a John Zorn-produced evening at the New A4-year-old son through serial nightmares. School’s Tishman Auditorium, then worked three consecutive It was our second rescheduling moment of the week. Six nights as a sidewoman, first in saxophonist Jure Pukl’s quintet days earlier, we postponed our first scheduled interview when at the Cornelia Street Café in Greenwich Village, then in a Davis awoke in the morning with a stomach virus her son had quintet assembled by Revis to play a newly commissioned suite picked up at school. -

HDO 191 Redux

HDO 191 Redux El contrabajista y compositor Pablo Martín Caminero pasará por HDO para presentar Salto al vacío, su nueva grabación que presentará el 11 de noviembre en el Festival de Jazz de Madrid. En la entrega 191 de HDO se podrá escuchar la voz de este músico, y también música de esta nueva grabación. En HDO 191 Redux está disponible un adelanto del programa, en menos de seis minutos, que estará disponible próximamente en Tomajazz. HDO 190. En concierto con… René Marie [Podcast] La cantante René Marie va a actuar en nuestro país en el IV San Miguel Jamboree Jazz Club Festival en Barcelona (sábado 5 de noviembre de 2016), el Festival Internacional de Jazz de Madrid (miércoles 9), y el Festival de Jazz de Palencia (viernes 11). Esta veterana (nació en 1955), decidió dedicarse por entero al jazz a una edad muy poco habitual: 42 años y tras un ultimátum de su marido, que le planteó elegir entre él o el jazz… y eligió el jazz. Gran cantante, que se mueve con mucha comodidad por distintos registros, y compositora, deja buena muestra de ello tanto en sus conciertos, como en sus grabaciones. En HDO 190 revisamos sus tres últimas grabaciones: Sound of Red (que ya sonó en HDO 149), I wanna be Evil, y Black Lace Freudian Sleep. © Pachi Tapiz, 2016 HDO es un podcast editado, producido y presentado por Pachi Tapiz. HDO 189. Ingrid Laubrock: her voice and her musics… interview by Pachi Tapiz [Podcast] Ingrid Laubrock will play in Spain. Her Anti-House 4 (Laubrock herself, Mary Halvorson, Kris Davis, Tom Rainey) will play at Jamboree (Barcelona), Bogui Jazz (Jazz Con Sabor a Club – Festival Internacional de Jazz de Madrid), and Campus Jazz Festival in Cádiz.Pachi Tapiz interviews her in the HDO Tomajazz podcast. -

The Extradition Series Leaven Community Center, Portland

The Extradition Series THE PIECES Jurg Frey, Glafsered I Glafsered II Glafsered IV (2002). Swiss composer Leaven Community Center, Portland Jurg Frey, a mainstay of the Wandelweiser group, has long pursued a flexible January 21, 2017 approach to the canon form, often obscuring its strict musical structure by building it from silences and non-specific sounds. This performance links three of his earliest canons: Glafsered I for crotales and tuned flagstones, Glafsered II for piano and bass clarinet, and Glafsered IV for bass clarinet, crotales, and tuned flagstones. The titles refer to the village of Glafsered in Jurg Frey, southeastern Sweden, home to curator and canon enthusiast Björn Nilsson. Glafsered I Glafsered II Glafsered IV For this performance, the three pieces will be played sequentially, with short silences between. We ask that audience members also remain quiet during Loren Chasse & Matt Hannafin (percussion), these silences. Dana Reason (piano), Jonathan Sielaff (bass clarinet) Dana Reason, Proxemics (2017). Taking its cue from the discipline of proxemics — which studies how people convey cultural, behavioral, and Dana Reason, Proxemics sociological messages through the amount of personal space they keep between themselves and others — Proxemics is a kind of modular-action Lee Elderton (B♭ clarinet), Matt Hannafin (percussion), music that explores various sonic and personal spaces. Scored for any Catherine Lee (oboe), Dana Reason (piano), number and variety of instruments and comprising different “sections” of Andre St. James (double bass) generative materials (text instructions, templates, written melodies, concepts) that can be played in any order, the piece requires performers to oscillate between personal and public space, generating new sound patterns Vanessa Tomlinson, Still and Moving Paper and experiences as they reify the generative materials, and sounding them against the articulations of the rest of the ensemble. -

Freier Download BA 104 Als

BAD 104 ALCHEMY Gone, gone, gone... [31 May 2019] Roky Erickson (The 13th Floor Elevators), 71 [01 Jun 2019] Michel Serres (Philosoph der Parasiten, Gemenge und Gemische), 88 [06 Jun 2019] Dr. John Mac Rebennack (the Night Tripper w/ New Orleans R&B), 77 [22 July 2019] Brigitte Kronauer (Teufelsbrück, Zwei schwarze Jäger), 78 [11 Sep 2019] Daniel Johnston (American singer-songwriter), 58 [30 Sep 2019] Gianni Lenoci (italienischer NowJazz-Pianist), 56 [06 Oct 2019] Ginger Baker (Trommelfeuerkopf bei Cream, Air Force...), 80 [03 Nov 2019] Katagiri Nobukazu (der Drummer von Ryorchestra) Hirnschlag BA's Top Ten 2019 Arashi - Jikan (PNL) d.o.o.r - Songs from a Darkness (poise) Fire! Orchestra - Arrival (Rune Grammofon) Kamilya Jubran & Werner Hasler - Wa (Everest) Land of Kush - Sand Enigma (Constellation) Les Comptes De Korsakoff - Nos Amers (Puzzle) MoE & Pinquins - Vi som elsket kaos (ConradSound) Stephanie Pan - Have Robot Dog, Will Travel (Arteksounds) Andrew Poppy - Hoarse Songs (Field Radio) La STPO - L'Empreinte (The Legacy) (Azafran Media) Die Macht eines Buches, ganz gleich welchen Buches, ... liegt darin, daß es eine offenstehende Tür ist, durch die man abhauen kann. Ich unterstreiche abhauen. Julien Green ...ein Kraut Schmerzenlos, einen Tropfen Todvorbei, einen Löffel Barmherzigkeit. Alles auf des Messers Schneide: Lachen, Weinen, Worte. Ernst Wiechert Honoré de Balzac - Verlorene Illusionen Karl Heinz Bohrer - Granatsplitter Charlotte Brontë - Erzählungen aus Angria Albert Camus - Der Fall ... Das Exil und das Reich Joseph Conrad - Taifun Jean-Pierre Gibrat - Mattéo: August 1936 André Gide - Die Verliese des Vatikan Julien Green - Der Geisterseher; Tagebücher 1996 bis 1998 Ernst Jünger - Eumeswil [nochmal] Daniel Kehlmann - Tyll Esther Kinsky - Hain Sibylle Lewitscharoff - Blumenberg Henry de Montherlant - Das Chaos und die Nacht [noch besser als beim ersten Mal] Walter Muschg - Tragische Literaturgeschichte Raymond Queneau - Mein Freund Pierrot Hugo Pratt - Corto Maltese: Das Goldene Haus von Samarkand .. -

The Allure of Chaotic Synergy in Grateful Dead Improvisation and Musical Dialogue

“It All Rolls into One:” The Allure of Chaotic Synergy in Grateful Dead Improvisation and Musical Dialogue Jim Tuedio Grateful Dead music is renowned for its improvisational qualities. The “psychedelic synergy” characteristic of Grateful Dead improvisation was a hallmark of thirty years of constant touring, and the rapturous allure of the musical space sustained by the band’s live performances produced a veritable culture of “tour heads” in love with the sound. Deadheads will swear the Grateful Dead improvised in a style all their own. Indeed, Grateful Dead concerts became something of a fountainhead for richly attuned, mind- altering experiences. Yet mainstream discussions of musical improvisation offer only passing references to this phenomenon to suggest anything extraordinary might have been going on. In what follows, I will attempt a discussion of Grateful Dead improvisation from the standpoint of the listener immersed in musical synergy. My goal is to explore the allure of “chaotic synergy” in Grateful Dead improvisation from a standpoint of musical embodiment. While the best access to this synergistic immersion would be through the portal of a live concert, one can attempt a careful analysis of the productive tensions operating in the musical dialogue itself. To open a conceptual space for this analysis, we need a figurative portal to musical embodiment. To reveal this point of access, we will explore facets of a listener’s engagement in Grateful Dead “phase space.” As such, this analysis will constitute something more like a phenomenology than a musicology of group improvisation. The principle focus of my analysis will be the performative “plane of immanence” characteristic of Grateful Dead music. -

Thumbscrew-Never Is Enough PR

Bio information: THUMBSCREW Title: NEVER IS ENOUGH (Cuneiform Rune 478) Format: CD / VINYL (DOUBLE) / DIGITAL www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ How much is too much when it comes to THUMBSCREW? The All-Star Collective Trio Delivers a Decisive Answer with Their Sixth Album NEVER IS ENOUGH a Riveting Program of Originals by Tomas Fujiwara, Mary Halvorson and Michael Formanek A funny thing happened while Thumbscrew was hunkered down at City of Asylum, the Pittsburgh arts organization that has served as a creative hotbed for the collective trio via a series of residencies. Late in the summer of 2019 the immediate plan was for drummer Tomas Fujiwara, guitarist Mary Halvorson and bassist Michael Formanek to rehearse and record a disparate program of Anthony Braxton compositions they’d gleaned from his Tri-Centric Foundation archives, pieces released last year on The Anthony Braxton Project, a Cuneiform album celebrating his 75th birthday. At the same time, the triumvirate brought in a batch of original compositions that they also spent time refining and recording, resulting in Never Is Enough, a brilliant program of originals slated for release on Cuneiform. There’s a precedent for twined projects by the trio serving as fascinating foils for each other. In June 2018, Cuneiform simultaneously released an album of Thumbscrew originals, Ours, and Theirs, a disparate but cohesive session exploring music by the likes of Brazilian choro master Jacob do Bandolim, pianist Herbie Nichols, and Argentine tango master Julio de Caro. Those albums were also honed and recorded during a City of Asylum residency. While not intended as the same kind of dialogue, The Anthony Braxton Project and Never Is Enough do seem to speak eloquently (if cryptically) to each other.