PGSCA Bernard Zakheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall

Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall AAA.albro64 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall Identifier: AAA.albro64 Date: 1964 July 27 Creator: Albro, Maxine, 1903-1966 (Interviewee) Hall, Parker (Interviewee) McChesney, -

Schwartz, Ellen (1987). Historical Essay

VOLUME 1 The Nahl Family tTVt a c ^ _____^ 2 — / * 3 7 ? Z ^ ^ y r f T ^ - l f ------ p c r ^ ----- - /^ V - ---- - ^ 5Y 4 / *y!— ^y*i / L.^ / ^ y p - y v i r ^ ------ 4 0001 California Art Research Edited by Gene Hailey Originally published by the Works Progress Administration San Francisco, California 1936-1937 A MICROFICHE EDITION fssay a/M? ^iMiograp/uca/ iwprov^w^^ts Ellen Schwartz MICROFICHE CARDS 1-12 Laurence McGilvery La Jolla, California 1987 0002 California Art Research Edited by Gene Hailey Originally published by the Works Progress Administration San Francisco, California 1936-1937 A MICROFICHE EDITION uzz'r^ a?? ^z'sfon'ca/ Msay awtf ^zMognip^zca/ ZTMprov^zM^Mfs Ellen Schwartz MICROFICHE CARD 1: CONTENTS Handbook 0003-0038 Volume 1 0039-0168 Table of contents 0041-0044 Prefatory note 0046 Introduction 0047-0058 The Nahl Family 0060-0066 Charles Christian Heinrich Nahl 0066-0104 "Rape of the Sabines" 0045 "Rape of the Sabines" 0059 "Rape of the Sabines" 0092 Hugo Wilhelm Arthur Nahl 0105-0122 Virgil Theodore Nahl 0123-0125 Perham Wilhelm Nahl 0126-0131 Arthur Charles Nahl 0132 Margery Nahl 0133-0140 Tabulated information on the Nahl Family 0141-0151 Newly added material on the Nahl Family 0152-0166 Note on personnel 0167-0168 Volume 2 0169-0318 Table of contents 0171-0172 William Keith 0173-0245 "Autumn oaks and sycamores" 0173 Newly added material 0240-0245 Thomas Hill 0246-0281 "Driving the last spike" 0246 Newly added material 0278-0281 Albert Bierstadt 0282-0318 "Mt. Corcoran" 0282 Newly added material 0315-0318 Newly -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

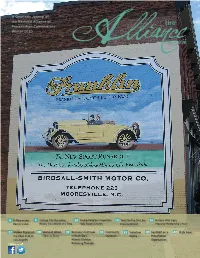

Winter 2020 Issue

A Quarterly Journal of the National Alliance of Preservation Commissions Winter 2020 4 In Memoriam: 6 Salvage City: Recycling 10 Saving Religious Properties: 15 Tools for the On-Line 16 Historic Wall Signs Bernie Callan History One Object at a Time Holy Rosary Church Preservationist Preserve Mooresville’s Past 22 Hidden Murals of 28 World of Wood, 32 Recovery Continues 35 Community 37 Volunteer 40 Spotlight on a 42 State News the Ebell Club of Clear as Glass in Nashville’s Outreach Profi le Preservation Los Angeles Historic Districts Organization Follow us on Following Tornado COVER IMAGE Although not a restoration, the Franklin Automobile Company 2020 BOARD OF DIRECTORS: sign adds to the commercial heritage of downtown The National Alliance of Preservation Commissions (NAPC) is governed by a Mooresville, North Carolina. Credit: Town of Mooresville board of directors composed of current and former members and staff of local preservation commissions and Main Street organizations, state historic preserva- tion office staff, and other preservation and planning professionals, with the Chair, Vice Chair, Secretary, Treasurer, and Chairs of the board committees serving as the Updated: 4.27.20 Board’s Executive Committee. the OFFICERS CORY KEGERISE WALTER GALLAS A quarterly journal with Pennsylvania Historical and Museum City of Baltimore news, technical assistance, Commission Maryland | Secretary and case studies relevant to Pennsylvania | Chair local historic preservation commissions and their staff. COLLETTE KINANE PAULA MOHR Raleigh Historic -

Ethnicity and Faith in American Judaism: Reconstructionism As Ideology and Institution, 1935-1959

ETHNICITY AND FAITH IN AMERICAN JUDAISM: RECONSTRUCTIONISM AS IDEOLOGY AND INSTITUTION, 1935-1959 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Deborah Waxman May, 2010 Examining Committee Members: Lila Corwin Berman, Advisory Chair, History David Harrington Watt, History Rebecca Trachtenberg Alpert, Religion Deborah Dash Moore, External Member, University of Michigan ii ABSTRACT Title: Ethnicity and Faith in American Judaism: Reconstructionism as Ideology and Institution, 1935-1959 Candidate's Name: Deborah Waxman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2010 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Lila Corwin Berman This dissertation addresses the development of the movement of Reconstructionist Judaism in the period between 1935 and 1959 through an examination of ideological writings and institution-building efforts. It focuses on Reconstructionist rhetorical strategies, their efforts to establish a liberal basis of religious authority, and theories of cultural production. It argues that Reconstructionist ideologues helped to create a concept of ethnicity for Jews and non-Jews alike that was distinct both from earlier ―racial‖ constructions or strictly religious understandings of modern Jewish identity. iii DEDICATION To Christina, who loves being Jewish, With gratitude and abundant love iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is the product of ten years of doctoral studies, so I type these words of grateful acknowledgment with a combination of astonishment and excitement that I have reached this point. I have been inspired by extraordinary teachers throughout my studies. As an undergraduate at Columbia, Randall Balmer introduced me to the study of American religious history and Holland Hendrix encouraged me to take seriously the prospect of graduate studies. -

Coit Tower Brochure V4 16 9 032016.Indd

SCULPTURE COIT TOWER PIONEER PARK Above the main entrance to the tower is a cast con- Coit Tower, a fluted, reinforced concrete column, rises The green summit of Telegraph Hill is called Pioneer crete, high-relief plaque of the phoenix with out- THE STORY OF 212 feet above Telegraph Hill and offers magnificent Park, so named for the group of public spirited cit- stretched wings, sculpted by Robert B. Howard. This views of the Bay Area from an observation gallery izens who bought the land and gave it to the city mythical bird, reborn in fire, is a symbol of San Francis- at its top. Its architect was Henry Howard, working in 1876. Because of its commanding views, the hill co, whose history is punctuated by many catastrophic COIT for the firm of Arthur Brown, Jr., which created San housed a signal station in 1849 to relay news of ships blazes. In the center of the parking plaza stands a 12’ TOWER bronze statue of Christopher Columbus by Vitorio Di Francisco’s City Hall and Opera House. Contrary entering the Bay to the business community along Colvertaldo. It was given to the city by its Italian com- to popular belief, it was never intended to resemble Montgomery Street, hence the name Telegraph Hill. munity in 1957. And Its Art a firehose nozzle. Howard’s simple, vertical design San Francisco’s contact with the world then was by Frescoes depicting“Life in California...1934.” was selected because it best created a monumental sea, and all arrivals were important events. In the SOCIAL REALISM AND statement within the small site and small budget of 1880s, the site briefly contained an observatory and A legacy of 25 Artists of Social Realism and their Assistants. -

A New Age for Artists

A NEW AGE FOR ARTISTS: THE BIRTH OF THE NEW DEAL ART MOVEMENT AND THE POLITICAL CONNOTATIONS OF THE COlT TOWER MURALS Timothy Rottenberg Prior to 1934, public art did not exist in the United States ofAmerica. Occasionally, paintings by individual artists would achieve success and break out of the art gallery and private commission sphere into the public eye, but visibility was not widespread. With the construction of Coit Tower in San Francisco, the creation of the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) in ‘934, and the unemployment of artists due to the Great Depression, a unique synchronistic moment came about when the birth of public art in America was forged. For the first time in American history, the PWAP gave artists the opportunity to reflect local and national politics through their own political lens using a medium that was meant for mass consumption by the public.i In January of there was nothing exciting about the San Fran cisco skyline. The city’s two tallest buildings stood at a stout 435 feet, and lay inconspicuously in the valley of the financial district, dwarfed even by the seven natural hills of San Francisco that surrounded them. With the Golden Gate and Bay bridges only in the earliest stages of construction, San Francisco lacked architectural individuality. Appropriately, Lillie Hitchcock Coit, a wealthy and eccentric San Francisco resident, desired beautification for the city she so admired. Despite having been born in Maryland and living in France for a number of years, the allure of the I believe this thesis to be wholly original in the field of historical study on the Public Works Administration as it related to the field of public art in America. -

Fffl'i2 MUSEUM of MODERN

I fffl'i2 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ;t1 WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK TELEPHONE! CIRCLE 7-7470 FOR RELEASE Saturday or Sun day, September 12 or 13,1936 The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, announces th irst exhibition of its 1936-37 season, Hew Horizons in American Art, which fell open to the public Wednesday, September 16 and will remain on view through Monday, October 12. The exhibition will consist of out standing work done since August 1935 by artists throughout the country on the Federal Art Project in the fields of mural painting, oils, viatercolors, sculpture, prints, posters, photographs, drawings and s ovor al hundr od watercolor plates. It will include / .. objects and will fill three and one-half floors of the Museum. The exhibition has been directed by Miss Dorothy C. Miller, Assistant Curator of .Painting and Sculpture of the Museum of Modern Art. The selections have been made without regard to regional representation, although many projects throughout the country will be included. Holger Cahill, Director of the Federal Art Project, believes that the support and stimulation of an interested public is as ne- cessar;/ to the artist as is a responsive audience to the actor. In his foreword to the catalog of Hew Horizons in American Art, he makes this clear. "An attempt to bridge the gap between the American artist and the American public has governed the entire program of the Federal Art Project," Mr. Cahill states. "For the first time in American art history a direct and sound relationship has been established between the American public and the artist. -

KOZA-DOCUMENT-2019.Pdf (2.191Mb)

Grove Hall Public Art Project: Impact on Community and Cityscape The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Koza, Anne. 2019. Grove Hall Public Art Project: Impact on Community and Cityscape. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365397 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Grove Hall Public Art Project: Impact on Community and Cityscape Anne Elizabeth Koza A Thesis in the Field of Visual Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2019 Copyright 2019 [Anne Elizabeth Koza] Abstract This thesis examines three murals created through The Grove Hall Public Art Project. This federally funded public arts grant awarded $70,000 from the Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Choice Neighborhoods Implementation (CNI) Grant to transform the cityscape in Grove Hall, Boston. Addressing American murals in a historic context, as socially engaged art, and examining the history of the community of Grove Hall this thesis evaluates the Grove Hall murals in relation to their value to the Grove Hall community as agents for social change. Frontispiece iv Dedication I dedicate this to all those who told me “just write.” So much of this process for me was an internal battle of getting myself to sit down and put proverbial pen to paper. -

The Art of Nation-Building: Two Murals by Charles Comfort (1936-37) Gillian Maccormack

The Art of Nation-Building: Two Murals by Charles Comfort (1936-37) Gillian MacCormack A Thesis in the Department of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Art History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2016 © Gillian MacCormack, 2016 2 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Gillian MacCormack Entitled: The Art of Nation-Building: Two Murals by Charles Comfort (1936-37) and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Art History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: ___________________________________ Chair Dr. Elaine Paterson ___________________________________ Examiner Dr. Elaine Paterson ___________________________________ Examiner Dr. Anne Whitelaw ___________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Nicola Pezolet Approved by: __________________________________ Dr. Kristina Huneault Graduate Program Director ____________ 2016 __________________________________ Rebecca Taylor Duclos Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts iii ABSTRACT The Art of Nation-Building: Two Murals by Charles Comfort (1936-37) Gillian MacCormack In the late 1920s, Canada experienced a new wave of nation-building art as part of a major mural movement sweeping Europe and North America. It reached its zenith in the 1930s, and provides the context – artistically, socially, politically and economically – for the two murals considered in this thesis. Such murals were modern in their focus on contemporary, usually urban issues, industrial subject matter, the image of the blue collar worker and its links to the Art Deco movement – “that vehicle of moderate nationalism” as architectural historian, Michael Windover, put it. -

Oral History Interview with Suzanne Scheuer, 1964 July 29

Oral history interview with Suzanne Scheuer, 1964 July 29 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Suzanne Scheuer on July 29, 1964. The interview took place in Santa Cruz, California, and was conducted by Mary Fuller McChesney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Mrs. McChesney's husband, Robert McChesney, was also present. Suzanne Scheuer and Mary Fuller McChesney have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MARY McCHESNEY: This is Mary Fuller McChesney interviewing Suzanne Scheuer at her home in Santa Cruz, California. The date is July 29, 1964. Miss Scheuer, first I'd like to ask you, where did you get your art training? SUZANNE SCHEUER: I got my art training first at the California school of Arts and Crafts when it was still in Berkeley and graduated with, first, a fine arts major, and then later I went back and got a teacher's credential. Ten years later I went to the California School of Fine Arts and studied mural painting with Ray Boynton. I was there two and a half or three years. MRS. McCHESNEY: That's the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco? MS. SCHEUER: Yes. It now has another name. MRS. McCHESNEY: San Francisco Art Institute, I believe it's called. -

Oral History Interview with Helen and Margaret Bruton, 1964 December 4

Oral history interview with Helen and Margaret Bruton, 1964 December 4 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Helen Bruton and Margaret Bruton on December 4, 1964. The interview was conducted at the Bruton's home at 871 Cass Street, Monterey, California by Lewis Ferbrache for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview LF: Lewis Ferbrache HB: Helen Bruton MB: Margaret Bruton LF: Lewis Ferbrache interviewing Miss Margaret Bruton and Miss Helen Bruton at their home, 871 Cass Street, Monterey, California, December 4, 1964. Miss Margaret Bruton, I believe you told me that you were born in Brooklyn, New York. Could you then tell about your Alameda, California school training in art? MB: Well, I was born in Brooklyn, but I went to school in Alameda, California. All my schooling was in Alameda, except when I went to art school, that was in San Francisco, at what was then the Mark Hopkins. I was there for about a year and then I – LF: Mark Hopkins School of Design, now the San Francisco Art Institute? MB: Yes. I won a scholarship for the Art Students League in New York so I went there and was studying there for quite a while. I studied with Robert Henri at the Art Students League. LF: Do you remember what year this would be, just for the record? MB: Well, it was about 1917, I think, it was just before the war – LF: Who were your teachers at the Mark Hopkins School of Design? That would be interesting.