A New Age for Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall, 1964 July 27

Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall, 1964 July 27 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH MAXINE ALBRO HALL AND PARKER HALL CONDUCTED JULY 27, 1964, BY MARY MCCHESNEY, IN CARMEL, CALIF. Interview MARY McCHENSNEY: First, I'd like to ask you a few questions about where you had your art school training. According to this little brochure that you have from your last exhibition, which was in January this year, did you say you studied in San Francisco? MAXINE ALBRO: Well -- first I began at the California School of Fine Arts and then I went for one winter to the Art Students League in New York. Then the next year I went to the Ecole de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris and then after coming home, I decided to go to Mexico and study with Diego Rivera. I did get down to Mexico and I did study fresco painting with Diego's assistant but I never studied with Diego, himself. I watched him (Diego) as he worked and got acquainted with him and we talked a little bit, a little bit in Spanish, a little bit in English. I enjoyed talking and watching him but I never studied with Diego. Although watching Diego was very beneficial to me. MS. McCHESNEY: What was the name of the man you studied with, Diego's assistant? MS. ALBRO: Paul O'Higgins was his assistant. He was an American young man and helped Diego in many ways. -

Fort Mason Extension SPUR Preso 101911

Extending Success: Streetcars to Ft. Mason Rick Laubscher, Doug Wright, Rich Hillis SPUR, October 19, 2011 Historic Streetcars: Huge SF Success ! “Trolley Festival” started Trolley Festival, 1983 momentum 28 years ago ! Used Market St. surface track ! Chamber-City joint project ! Mayor Feinstein was champion ! Community support led to: ⊕" 5-summer run ⊕" Adoption of permanent F-line F-line, Pier 39, 2000 ! F-line open 1995; to Wharf 2000 ! Today: 23,000+ daily riders ⊕" Most popular vintage line in U.S. ⊕" Service increased to meet demand ⊕" Still more service needed Rail’s Role: Commerce, Commuters, Defense Ferry Bldg. 1927 ! Waterfront rail – 1900-c.1960s ⊕" State Belt freight RR served piers ⊕" Supplies, troops carried to Fort Mason & Presidio on Army track ⊕" 25 streetcar lines served waterfront ♦"World’s 2nd busiest transit hub ! Maritime & defense evolved ⊕" Waterfront’s face changed forever ⊕" Today: recreation, visitor oriented Troop Train at Crissy Field 1941 Fort Mason Streetcar History ! Muni’s H-line served Fort Mason 1914-1948 Fort Mason Streetcar Revival ! Historic waterfront streetcar line repeatedly proposed ⊕" 1970: San Francisco Tomorrow suggests waterfront route ⊕" 1979: First Muni Embarcadero streetcar proposal included in plan ⊕" 1980: GGNRA General Management Plan proposes historic streetcar shuttle from Aquatic Park to Crissy Field ⊕" 1985: I-280 Transfer Study evaluates Caltrain-Fort Mason route ⊕" 2000: F-line extension opens to Wharf ⊕" 2001: Fort Mason Center, Fisherman’s Wharf Merchants, Market Street Railway -

San Francisco Museum & Historical Society Complete List of Argonaut Articles

San Francisco Museum & Historical Society Complete List of Argonaut Articles Vol. 1, No. 1 Spring, 1990 Great San Francisco Fire and Earthquake of 1906: Arthur C. Poore My Experiences and Impressions Vol. 1, No. 1 Spring, 1990 Provincial Italian Cuisines - San Francisco’s Role Deanna Paoli Gumina as Conservator of the Italian Heritage Vol. 2, No. 1 Fall, 1991 1906 Afterquakes: Unsung Heroes and Political Mae Silver Scandal Vol. 2, No. 1 Fall, 1991 What Really Happened to Police Chief Biggy? Kevin Mullen Vol. 3, No. 1 Winter, 1992 Lone Mountain & Laurel Hill Cemeteries Deanna L. Kastler Vol. 3, No. 1 Winter, 1992 Vigilante Rebirth: The Civil War Union League Dr. Robert J. Chandler Vol. 4, No. 1 Summer, 1993 Histories and Mysteries Don Herron Vol. 4, No. 1 Summer, 1993 Call Building: San Francisco’s Forgotten Ellen Klages Skyscraper Vol. 4, No. 1 Summer, 1993 History of Union Square Gregory J. Nuno Vol. 5, No. 1 Spring, 1994 Pictures of an Exposition: Isaiah W. Taber and the Rodger C. Birt San Francisco Midwinter Fair Vol. 5, No. 1 Spring, 1994 San Francisco’s Fallen Starr: The Death and Richard H. Peterson Legacy of Thomas Starr King in Calif.1860-64 Vol. 5, No. 1 Spring, 1994 Limantour Claims Michael Griffith Vol. 5, No. 1 Spring, 1994 Love Book, the Counterculture, and the Catholic Jeffrey M. Burns City Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall, 1994 Crissy Field: The Last Word in Airfields Stephen A. Haller Vol. 5, No. 2 Fall, 1994 Pedro Benito Cambon, OFM: Mission Builder Par Frank J. Portman Excellence Vol. -

Oral History Interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall

Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall AAA.albro64 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Maxine Albro and Parker Hall Identifier: AAA.albro64 Date: 1964 July 27 Creator: Albro, Maxine, 1903-1966 (Interviewee) Hall, Parker (Interviewee) McChesney, -

Armchair Travel Destination - United States of America San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers

Armchair Travel _ Destination - United States of America _ San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers The Conservatory of Flowers at Golden Gate Park opened in Golden Gate Park in 1879. A powerful storm destroyed the glass and wood greenhouse in 1998, causing the conservatory to temporarily close. In 2003, the conservatory reopened after extensive reconstruction. The Conservatory features more than 1,700 varieties of tropical plants, from palms to cycads to cacao. In its five galleries, this modern horticultural museum displays many endangered species from over 50 countries and focuses on conservation education. © Copyright [email protected] 2017. All Rights Reserved 1 Armchair Travel _ Destination - United States of America _ San Francisco City Hall Designed by Arthur Brown Jr. as a civic center, the San Francisco City Hall was part of the American Renaissance movement—a period when the United States experienced a rebirth in literature, art, architecture, and music. It was built to replace the previous city hall, which was destroyed in an earthquake in 1906. The current city hall, which occupies two city blocks, opened its doors in 1915. © Copyright [email protected] 2017. All Rights Reserved 2 Armchair Travel _ Destination - United States of America _ San Francisco Alcatraz The U.S. government built a lighthouse on Alcatraz Island in 1854. Beginning in 1859, Alcatraz, otherwise known as the Rock, served as a fortress and military prison to defend San Francisco Bay. Due to high operating costs, the government turned Alcatraz over to the Federal Bureau of Prisons in 1934. The Rock was a federal penitentiary until 1963. -

Schwartz, Ellen (1987). Historical Essay

VOLUME 1 The Nahl Family tTVt a c ^ _____^ 2 — / * 3 7 ? Z ^ ^ y r f T ^ - l f ------ p c r ^ ----- - /^ V - ---- - ^ 5Y 4 / *y!— ^y*i / L.^ / ^ y p - y v i r ^ ------ 4 0001 California Art Research Edited by Gene Hailey Originally published by the Works Progress Administration San Francisco, California 1936-1937 A MICROFICHE EDITION fssay a/M? ^iMiograp/uca/ iwprov^w^^ts Ellen Schwartz MICROFICHE CARDS 1-12 Laurence McGilvery La Jolla, California 1987 0002 California Art Research Edited by Gene Hailey Originally published by the Works Progress Administration San Francisco, California 1936-1937 A MICROFICHE EDITION uzz'r^ a?? ^z'sfon'ca/ Msay awtf ^zMognip^zca/ ZTMprov^zM^Mfs Ellen Schwartz MICROFICHE CARD 1: CONTENTS Handbook 0003-0038 Volume 1 0039-0168 Table of contents 0041-0044 Prefatory note 0046 Introduction 0047-0058 The Nahl Family 0060-0066 Charles Christian Heinrich Nahl 0066-0104 "Rape of the Sabines" 0045 "Rape of the Sabines" 0059 "Rape of the Sabines" 0092 Hugo Wilhelm Arthur Nahl 0105-0122 Virgil Theodore Nahl 0123-0125 Perham Wilhelm Nahl 0126-0131 Arthur Charles Nahl 0132 Margery Nahl 0133-0140 Tabulated information on the Nahl Family 0141-0151 Newly added material on the Nahl Family 0152-0166 Note on personnel 0167-0168 Volume 2 0169-0318 Table of contents 0171-0172 William Keith 0173-0245 "Autumn oaks and sycamores" 0173 Newly added material 0240-0245 Thomas Hill 0246-0281 "Driving the last spike" 0246 Newly added material 0278-0281 Albert Bierstadt 0282-0318 "Mt. Corcoran" 0282 Newly added material 0315-0318 Newly -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

Clyde Wahrhaftig Collection

Clyde Wahrhaftig Collection GOGA 35329 Golden Gate National Recreation Area Park Archives and Records Center ATTN: Park Archives and Records Center Presidio of San Francisco Building 201, Fort Mason Building 667 McDowell Ave. San Francisco, CA 94123 San Francisco, CA 94129 [Mailing Address] [Physical Address] go.nps.gov/gogacollections Phone: 415-561-2807 Fax: 415-441-1618 Introduction Golden Gate National Recreation Area Park Description Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), a unit of the National Park Service, was established by an Act of Congress on October 27, 1972. The 80,000-acre park encompasses a great diversity of cultural and natural resources in and around the Bay Area of San Francisco, California. It includes Muir Woods National Monument and Fort Point National Historic Site. The park holds almost five million three-dimensional and documentary artifacts dating from the time before European contact to the present. They are preserved and maintained for the public by the Division of Cultural Resources and Museum Management, which includes the Park Archives and Records Center (PARC). Park Archives and Records Center (PARC) Historical Note GGNRA and the sites within it have been collecting records since their inception. The PARC was established in 1994 to receive records and archival collections from the U.S. Army and the Presidio Army Museum after the closure of the Presidio of San Francisco as an Army base. The collections continue to grow through the donation of materials by private individuals, transfer of inactive park records by staff, and acquisition of relevant documentary materials. Scope of Collections The archival collections in the custody of the GGNRA document the history and activity of the various sites and groups associated with the park, described in the park’s Scope of Collection Statement (2009). -

An Art-Lovers Guide to the Exposition

An Art−Lovers guide to the Exposition Shelden Cheney An Art−Lovers guide to the Exposition Table of Contents An Art−Lovers guide to the Exposition..................................................................................................................1 Shelden Cheney..............................................................................................................................................1 Foreword........................................................................................................................................................2 The Architecture and Art as a Whole.............................................................................................................2 The Court of Abundance................................................................................................................................5 Court of the Universe.....................................................................................................................................9 Court of the Four Seasons............................................................................................................................14 The Court of Palms and the Court of Flowers.............................................................................................17 The Tower of Jewels, and the Fountain of Energy......................................................................................19 Palaces Facing the Avenue of Palms...........................................................................................................22 -

Winter 2020 Issue

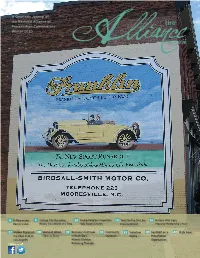

A Quarterly Journal of the National Alliance of Preservation Commissions Winter 2020 4 In Memoriam: 6 Salvage City: Recycling 10 Saving Religious Properties: 15 Tools for the On-Line 16 Historic Wall Signs Bernie Callan History One Object at a Time Holy Rosary Church Preservationist Preserve Mooresville’s Past 22 Hidden Murals of 28 World of Wood, 32 Recovery Continues 35 Community 37 Volunteer 40 Spotlight on a 42 State News the Ebell Club of Clear as Glass in Nashville’s Outreach Profi le Preservation Los Angeles Historic Districts Organization Follow us on Following Tornado COVER IMAGE Although not a restoration, the Franklin Automobile Company 2020 BOARD OF DIRECTORS: sign adds to the commercial heritage of downtown The National Alliance of Preservation Commissions (NAPC) is governed by a Mooresville, North Carolina. Credit: Town of Mooresville board of directors composed of current and former members and staff of local preservation commissions and Main Street organizations, state historic preserva- tion office staff, and other preservation and planning professionals, with the Chair, Vice Chair, Secretary, Treasurer, and Chairs of the board committees serving as the Updated: 4.27.20 Board’s Executive Committee. the OFFICERS CORY KEGERISE WALTER GALLAS A quarterly journal with Pennsylvania Historical and Museum City of Baltimore news, technical assistance, Commission Maryland | Secretary and case studies relevant to Pennsylvania | Chair local historic preservation commissions and their staff. COLLETTE KINANE PAULA MOHR Raleigh Historic -

2015-011315Fed

National Register Nomination Case Report HEARING DATE: OCTOBER 21, 2015 Date: October 21, 2015 Case No.: 2015-011315FED Project Address: 800 Chestnut Street (San Francisco Art Institute) Zoning: RH-3 (Residential House, Three-Family) 40-X Height and Bulk District Block/Lot: 0049/001 Project Sponsor: Carol Roland-Nawi, Ph.D., State Historic Preservation Officer California Office of Historic Preservation 1725 23rd Street, Suite 100 Sacramento, CA 95816 Staff Contact: Shannon Ferguson – (415) 575-9074 [email protected] Reviewed By: Timothy Frye – (415) 575-6822 [email protected] Recommendation: Send resolution of findings recommending that, subject to revisions, OHP approve nomination of the subject property to the National Register BACKGROUND In its capacity as a Certified Local Government (CLG), the City and County of San Francisco is given the opportunity to comment on nominations to the National Register of Historic Places (National Register). Listing on the National Register of Historic Places provides recognition by the federal government of a building’s or district’s architectural and historical significance. The nomination materials for the individual listing of the San Francisco Art Institute at 800 Chestnut Street were prepared by Page & Turnbull. PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 800 Chestnut Street, also known as the San Francisco Art Institute, is located in San Francisco’s Russian Hill neighborhood on the northwest corner of Chestnut and Jones streets. The property comprises two buildings: the 1926 Spanish Colonial Revival style original building designed by Bakewell & Brown (original building) and the 1969 Brutalist addition designed by Paffard Keatinge-Clay (addition). Constructed of board formed concrete with red tile roofs, the original building is composed of small interconnected multi-level volumes that step up from Chestnut Street to Jones Street and range from one to two stories and features a five-story campanile, Churrigueresque entranceway and courtyard with tiled fountain. -

SERVICES for OPERATORS Group Rates/Discounts | Meal Voucher Program | Tour Planning PIER 39 Savings Fun Pack | FAM Tours

THIS IS YOUR OFFICIAL PIER 39 REFERENCE GUIDE, A TOOL CREATED TO ASSIST YOU AND YOUR CLIENTS WHEN PLANNING A VISIT TO PIER 39. For more information, please contact the PIER 39 Tourism Development Department. SERVICES FOR OPERATORS Group Rates/Discounts | Meal Voucher Program | Tour Planning PIER 39 Savings Fun Pack | FAM Tours PIER 39 Tourism Development Department Jodi Cumming | Director of Tourism Development | [email protected] | 415.705.5526 Rand Hardy | Tourism Development Manager | [email protected] | 415.705.5530 P.O. Box 193730 | San Francisco, CA 94119-3730 | PIER39.COM | 415.705.5500 WELCOME TO THE SAN FRANCISCO WATERFRONT From amazing views and a sea of sea lions to chowder bread bowls and California wines, a visit to San Francisco starts at PIER 39. Kick off your visit by exploring two levels of dining, entertainment, shopping and attractions, all surrounded by unbeatable views of the city and the bay. Take it from the world famous sea lions: a visit to San Francisco starts at The PIER. DISCOUNTED SHOPPING The PIER 39 Savings Fun Pack contains discounts and special offers from participating PIER 39 restaurants, shops and attractions. The Savings Fun Pack is a fantastic added-value for your clients visiting PIER 39. They are always free and can be shipped to you at no additional cost. We can also create a customized voucher for your clients that are redeemable for a Savings Fun Pack at the California Welcome Center. This voucher is also available in a variety of languages. To order a supply of Savings Fun Packs, please email [email protected] or call 415.705.5530.