Transcriptome Analysis of Genes and Pathways Associated with Metabolism in Scylla Paramamosain Under Different Light Intensities During Indoor Overwintering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sarcosine and Other Metabolites Along the Choline Oxidation Pathway in Relation to Prostate Cancer—A Large Nested Case–Control Study Within the JANUS Cohort in Norway

IJC International Journal of Cancer Sarcosine and other metabolites along the choline oxidation pathway in relation to prostate cancer—A large nested case–control study within the JANUS cohort in Norway Stefan de Vogel1, Arve Ulvik2, Klaus Meyer2, Per Magne Ueland3,4, Ottar Nyga˚rd5,6, Stein Emil Vollset1,7, Grethe S. Tell1, Jesse F. Gregory III8, Steinar Tretli9 and Tone Bjïrge1,7 1 Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 2 BEVITAL AS, Bergen, Norway 3 Section for Pharmacology, Institute of Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 4 Laboratory of Clinical Biochemistry, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway 5 Section for Cardiology, Institute of Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 6 Department of Heart Disease, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway 7 Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bergen, Norway 8 Food Science and Human Nutrition Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 9 The Cancer Registry of Norway, Oslo, Norway Methyl group donors and intermediates of one-carbon metabolism affect DNA synthesis and DNA methylation, and may thereby affect prostate carcinogenesis. Choline, the precursor of betaine, and the one-carbon metabolite sarcosine have been associated with increased prostate cancer risk. Within JANUS, a prospective cohort in Norway (n 5 317,000) with baseline serum samples, we conducted a nested case–control study among 3,000 prostate cancer cases and 3,000 controls. Using conditional logistic regression, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for prostate cancer risk were estimated according to quintiles of circulating betaine, dimethylglycine (DMG), sarcosine, glycine and serine. High sarcosine and glycine concentrations were associated with reduced prostate cancer risk of borderline significance (sarcosine: highest vs. -

Proton NMR Spectroscopic Analysis of Multiple Acyl-Coa Dehydrogenase Deficiencyðcapacity of the Choline Oxidation Pathway for Methylation in Vivo

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1406Ž. 1998 274±282 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Proton NMR spectroscopic analysis of multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiencyÐcapacity of the choline oxidation pathway for methylation in vivo Shamus P. Burns a, Heather C. Holmes a, Ronald A. Chalmers c, Andrew Johnson b, Richard A. Iles a,) a Medical Unit, Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Research Group, St. Bartholomew's and The Royal London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Whitechapel, London E1 1BB, UK b Biochemistry Unit, Institute of Child Health, London WC1N 1EH, UK c Paediatric Metabolism Unit, Department of Child Health, St. George's Hospital Medical School, London SW17 ORE, UK Received 20 January 1998; accepted 16 February 1998 Abstract Proton NMR spectra of urine from subjects with multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, caused by defects in either the electron transport flavoprotein or electron transport flavoprotein ubiquinone oxidoreductase, provide a characteris- tic and possibly diagnostic metabolite profile. The detection of dimethylglycine and sarcosine, intermediates in the oxidative degradation of choline, should discriminate between multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency and related disorders involving fatty acid oxidation. The excretion rates of betaine, dimethylglycineŽ. and sarcosine in these subjects give an estimate of the minimum rates of both choline oxidation and methyl group release from betaine and reveal that the latter is comparable with the calculated total body methyl requirement in the human infant even when choline intake is very low. Our results provide a new insight into the rates of in vivo methylation in early human development. -

Phylogeny and Evolution of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase-Homologous Folate Enzymes

Chemico-Biological Interactions 191 (2011) 122–128 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemico-Biological Interactions journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chembioint Phylogeny and evolution of aldehyde dehydrogenase-homologous folate enzymes Kyle C. Strickland a, Roger S. Holmes b, Natalia V. Oleinik a, Natalia I. Krupenko a, Sergey A. Krupenko a,∗ a Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC 29425 USA b School of Biomolecular and Physical Sciences, Griffith University, Nathan 4111 Brisbane, Queensland, Australia article info abstract Article history: Folate coenzymes function as one-carbon group carriers in intracellular metabolic pathways. Folate- Available online 6 January 2011 dependent reactions are compartmentalized within the cell and are catalyzed by two distinct groups of enzymes, cytosolic and mitochondrial. Some folate enzymes are present in both compartments Keywords: and are likely the products of gene duplications. A well-characterized cytosolic folate enzyme, FDH Folate metabolism (10-formyltetrahydro-folate dehydrogenase, ALDH1L1), contains a domain with significant sequence Mitochondria similarity to aldehyde dehydrogenases. This domain enables FDH to catalyze the NADP+-dependent 10-Formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase conversion of short-chain aldehydes to corresponding acids in vitro. The aldehyde dehydrogenase-like Aldehyde dehydrogenase Domain structure reaction is the final step in the overall FDH mechanism, by which a tetrahydrofolate-bound formyl group + Evolution is oxidized to CO2 in an NADP -dependent fashion. We have recently cloned and characterized another folate enzyme containing an ALDH domain, a mitochondrial FDH. Here the biological roles of the two enzymes, a comparison of the respective genes, and some potential evolutionary implications are dis- cussed. -

The Effect of Tetrahydrofolate on the Reduction of Electron Transfer Flavoprotein by Sarcosine and Dimethylglycine Dehydrogenases

Biochem. J. (1982) 203, 707-715 707 Printed in Great Britain The effect of tetrahydrofolate on the reduction of electron transfer flavoprotein by sarcosine and dimethylglycine dehydrogenases Daniel J. STEENKAMP and Mazhar HUSAIN Molecular Biology Division, Veterans Administration Medical Centre, San Francisco, CA 94121 and Department ofBiochemistry and Biophysics, University ofCalifornia, San Francisce, CA 94143, U.S.A. (Received 7 December 1981/Accepted 23 February 1982) Pig liver electron transfer flavoprotein (ETF) is rapidly reduced by sarcosine and dimethylglycine dehydrogenases to the anionic semiquinone form, the subsequent formation of the flavoquinol form being a much slower process. In the presence of tetrahydrofolate the yield of anionic semiquinone at the end of the rapid phase of reduction of ETF is only about 10% less than without tetrahydrofolate, as judged by e.p.r. spectroscopy. Tetrahydrofolate does not alter the rate of reduction of ETF by either sarcosine or dimethylglycine dehydrogenase. Nevertheless, it was clearly demon- strated that tetrahydrofolate is a substrate for both sarcosine and dimethylglycine dehydrogenases and is converted to N',10-methylenetetrahydrofolate. Sarcosine and dimethylglycine dehydrogenases creased incorporation of radioactivity from the (EC 1.5.99.1 and 1.5.99.2) are flavoproteins which N-methyl group of sarcosine into serine, sarcosine catalyse the oxidative N-demethylation of sarcosine oxidase activity was unaffected (Dac & Wriston, and dimethylglycine (MacKenzie & Abeles, 1956; 1958), -

Identification of Folate Binding Protein of Mitochondria As Dimethylglycine Dehydrogenase (Flavoprotein/Sarcosine Dehydrogenase/Tetrahydrofolate) ARTHUR J

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 77, No. 8, pp. 4484-4488, August 1980 Biochemistry Identification of folate binding protein of mitochondria as dimethylglycine dehydrogenase (flavoprotein/sarcosine dehydrogenase/tetrahydrofolate) ARTHUR J. WITTWER* AND CONRAD WAGNERt Department of Biochemistry, Vanderbilt University and Veterans Administration Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee 37203 Communicated by Sidney P. Colowick, April 24,1980 ABSTRACT The folate-binding protein of rat liver mito- Preparation of Tetrahydro[3H]folic Acid (H4[3HJPteGIu). chondria [Zamierowski, M. & Wagner, C. (1977) J. BioL Chem. [3',5',7,9-3H]PteGlu, potassium salt (20 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 3.7 252,933-9381 has been purified to homogeneity by a combina- tion of gel filtration, DEAE-cellulose, and affinity chromatog- X 101' becquerels) was obtained from Amersham. Unlabeled raphy. This protein was assayed by its ability to bind tetrahv- PteGlu (Sigma) was added to adjust the specific activity to 20 dro[3H folic acid in vitro. The purified protein contains tightly ,uCi/Amol. H4[3',5',7,9-3H]PteGlu was synthesized by chemical bound flavin and has a molecular weight of about 90,000 as reduction with NaBH4 (2). To 0.70 ml of 0.066 M Tris-HCI at determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate electrophoresis. This pH 7.8 was added 0.30 ml of a solution containing 0.40 protein also displays dimethylglycine deh drogenase [NN- ,gmol dimethylglycine: (acceptor) oxidoreductase (deme ylating), EC (8 ,Ci) of [3H]PteGlu. This solution was stirred in the dark 1.5.99.21 activity which copurifies with the folatebinding ac- under nitrogen at room temperature, and 0.25 ml of NaBH4 tivity. -

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

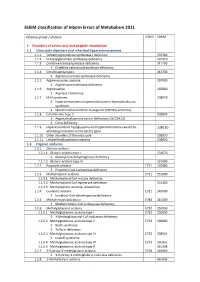

SSIEM Classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011

SSIEM classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011 Disease group / disease ICD10 OMIM 1. Disorders of amino acid and peptide metabolism 1.1. Urea cycle disorders and inherited hyperammonaemias 1.1.1. Carbamoylphosphate synthetase I deficiency 237300 1.1.2. N-Acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency 237310 1.1.3. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency 311250 S Ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency 1.1.4. Citrullinaemia type1 215700 S Argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency 1.1.5. Argininosuccinic aciduria 207900 S Argininosuccinate lyase deficiency 1.1.6. Argininaemia 207800 S Arginase I deficiency 1.1.7. HHH syndrome 238970 S Hyperammonaemia-hyperornithinaemia-homocitrullinuria syndrome S Mitochondrial ornithine transporter (ORNT1) deficiency 1.1.8. Citrullinemia Type 2 603859 S Aspartate glutamate carrier deficiency ( SLC25A13) S Citrin deficiency 1.1.9. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia and hyperammonemia caused by 138130 activating mutations in the GLUD1 gene 1.1.10. Other disorders of the urea cycle 238970 1.1.11. Unspecified hyperammonaemia 238970 1.2. Organic acidurias 1.2.1. Glutaric aciduria 1.2.1.1. Glutaric aciduria type I 231670 S Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.1.2. Glutaric aciduria type III 231690 1.2.2. Propionic aciduria E711 232000 S Propionyl-CoA-Carboxylase deficiency 1.2.3. Methylmalonic aciduria E711 251000 1.2.3.1. Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency 1.2.3.2. Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase deficiency 251120 1.2.3.3. Methylmalonic aciduria, unspecified 1.2.4. Isovaleric aciduria E711 243500 S Isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.5. Methylcrotonylglycinuria E744 210200 S Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency 1.2.6. Methylglutaconic aciduria E712 250950 1.2.6.1. Methylglutaconic aciduria type I E712 250950 S 3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency 1.2.6.2. -

Plasma Methylation Profile RESOURCE GUIDE

Plasma Methylation Profile RESOURCE GUIDE Science + Insight doctorsdata.com Methionine SAMe DNA SHMT THF RNA 5, 10 Methyltransferases MethyleneTHF Protein Thymidine DMG Lipids synthesis B12 BHMT SAH dUMP MTRR MTR TMG adenosine AHCY MTHFR Homocysteine 5 Methyl THF CBS Cystathionine Cysteine Sulte SUOX Sulfate Introduction The Plasma Methylation Profile is a functional assessment of the enzymes involved in methionine metabolism and the trans-sulfuration pathway (commonly called the “Methylation Pathway”). The genomics revolution has made it possible to assess genetic information stored in the DNA code. An awareness of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) has made genetic testing for certain SNPs part of diagnostic patient assessment. While the identification of SNPs in a patient’s genome is important, it is vital to remember that functional testing of enzymes should determine treatment decisions. There are many layers of translation between the genome and the enzyme. Enzyme function may be compromised not only by inheritance, but also by acquired epigenetic factors such as nutritional status, oxidative stress, autoimmunity or environmental exposures. There is mounting evidence that, especially within the folate and methylation pathways, multiple SNPs in multiple genes (haplotypes) may be necessary to alter metabolism or change health outcomes. Gastrointestinal functions may influence absorption, physiology, metabolism and immunity; nutrient maldigestion or malabsorption may inhibit normal enzyme functions, and may have greater effects on enzymes with SNPs. © 2016 Doctor’s Data, Inc. All rights reserved. doctorsdata.com Doctor’s Data, Inc. Plasma Methylation Enzyme and Nutrition Guide 2 Methionine High Methionine may be elevated for a variety of reasons. Several enzymes involved in the metabolism of methionine require magnesium and other nutritional cofactors. -

Folate Network Genetic Variation, Plasma Homocysteine, and Global

Chromosome LINE-1 elements elements LINE-1 Global genomic DNA methylation – methylation DNA genomic Global Alu elements Chromosome Global genomic DNA methylation – methylation DNA genomic Global Chromosome Plasma total homocysteine homocysteine total Plasma 10 P value value P log - Folate network genetic variation, plasma homocysteine, and global genomic methylation content: a genetic association study Wernimont et al. Wernimont et al. BMC Medical Genetics 2011, 12:150 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/12/150 (21 November 2011) Wernimont et al. BMC Medical Genetics 2011, 12:150 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/12/150 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Folate network genetic variation, plasma homocysteine, and global genomic methylation content: a genetic association study Susan M Wernimont1, Andrew G Clark2, Patrick J Stover1, Martin T Wells3, Augusto A Litonjua4, Scott T Weiss4, J Michael Gaziano5, Katherine L Tucker6, Andrea Baccarelli7,8, Joel Schwartz7, Valentina Bollati8 and Patricia A Cassano9* Abstract Background: Sequence variants in genes functioning in folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism are hypothesized to lead to changes in levels of homocysteine and DNA methylation, which, in turn, are associated with risk of cardiovascular disease. Methods: 330 SNPs in 52 genes were studied in relation to plasma homocysteine and global genomic DNA methylation. SNPs were selected based on functional effects and gene coverage, and assays were completed on the Illumina Goldengate platform. Age-, smoking-, and nutrient-adjusted genotype–phenotype associations were estimated in regression models. Results: Using a nominal P ≤ 0.005 threshold for statistical significance, 20 SNPs were associated with plasma homocysteine, 8 with Alu methylation, and 1 with LINE-1 methylation. -

Supplemental Figures 04 12 2017

Jung et al. 1 SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES 2 3 Supplemental Figure 1. Clinical relevance of natural product methyltransferases (NPMTs) in brain disorders. (A) 4 Table summarizing characteristics of 11 NPMTs using data derived from the TCGA GBM and Rembrandt datasets for 5 relative expression levels and survival. In addition, published studies of the 11 NPMTs are summarized. (B) The 1 Jung et al. 6 expression levels of 10 NPMTs in glioblastoma versus non‐tumor brain are displayed in a heatmap, ranked by 7 significance and expression levels. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. 8 2 Jung et al. 9 10 Supplemental Figure 2. Anatomical distribution of methyltransferase and metabolic signatures within 11 glioblastomas. The Ivy GAP dataset was downloaded and interrogated by histological structure for NNMT, NAMPT, 12 DNMT mRNA expression and selected gene expression signatures. The results are displayed on a heatmap. The 13 sample size of each histological region as indicated on the figure. 14 3 Jung et al. 15 16 Supplemental Figure 3. Altered expression of nicotinamide and nicotinate metabolism‐related enzymes in 17 glioblastoma. (A) Heatmap (fold change of expression) of whole 25 enzymes in the KEGG nicotinate and 18 nicotinamide metabolism gene set were analyzed in indicated glioblastoma expression datasets with Oncomine. 4 Jung et al. 19 Color bar intensity indicates percentile of fold change in glioblastoma relative to normal brain. (B) Nicotinamide and 20 nicotinate and methionine salvage pathways are displayed with the relative expression levels in glioblastoma 21 specimens in the TCGA GBM dataset indicated. 22 5 Jung et al. 23 24 Supplementary Figure 4. -

Components of the Choline Oxidation Pathway in Relation to Acute Myocardial Infarction, Type 2 Diabetes and Mortality

&RPSRQHQWVRIWKHFKROLQHR[LGDWLRQ SDWKZD\LQUHODWLRQWRDFXWHP\RFDUGLDO LQIDUFWLRQW\SHGLDEHWHV and mortality 3URVSHFWLYHREVHUYDWLRQDOVWXGLHVDPRQJSDWLHQWVZLWKVXVSHFWHGRU YHULILHGFRURQDU\KHDUWGLVHDVHLQ1RUZD\ *DUG)URGDKO7YHLWHYnJ6YLQJHQ Dissertation for the degree of philosophiae doctor (PhD) at the University of Bergen Dissertation date: $SULO © Copyright Gard Frodahl Tveitevåg Svingen The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Year: 2016 Title: Components of the choline oxidation pathway in relation to acute myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes and mortality. Prospective observational studies among patients with suspected or verified coronary heart disease in Norway Author: Gard Frodahl Tveitevåg Svingen Print: AiT Bjerch AS / University of Bergen ISBN 978-82-308-3360-5 Bergen, Norway 2016 2 LIST OF SELECTED ABBREVIATIONS ACE – Angiotensin converting enzyme ACS – Acute coronary syndrome ACVD– Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease AMI – Acute myocardial infarction Apo – Apolipoprotein BADH – Betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase BHMT – Betaine-homocysteine S-methyl transferase BMI – Body mass index CABG – Coronary artery bypass graft CAD – Coronary artery disease CHDH – Choline dehydrogenase CBS – Cystathionine-β-synthase CI – Confidence interval CoR – Coefficient of reliability CRP – C-reactive protein CVD – Cardiovascular disease DMG – Dimethylglycine DDH – Dimethylglycine dehydrogenase GAM – Generalized additive model GFR – Glomerular filtration rate GNMT – Glycine-N-methyltransferase HDL-C – High density lipoprotein cholesterol -

Riboflavin Deficiency—Implications for General Human Health and Inborn

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Riboflavin Deficiency—Implications for General Human Health and Inborn Errors of Metabolism 1, 1,2, 1 1 1 Signe Mosegaard y, Graziana Dipace y , Peter Bross , Jasper Carlsen , Niels Gregersen and Rikke Katrine Jentoft Olsen 1,* 1 Research Unit for Molecular Medicine, Department for Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University and Aarhus University Hospital, 8200 Aarhus N, Denmark; [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (G.D.); [email protected] (P.B.); [email protected] (J.C.); [email protected] (N.G.) 2 Department of Biosciences, Biotechnology and Biopharmaceutics, University of Bari ‘Aldo Moro’, 70121 Bari, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-78455412 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 30 April 2020; Accepted: 26 May 2020; Published: 28 May 2020 Abstract: As an essential vitamin, the role of riboflavin in human diet and health is increasingly being highlighted. Insufficient dietary intake of riboflavin is often reported in nutritional surveys and population studies, even in non-developing countries with abundant sources of riboflavin-rich dietary products. A latent subclinical riboflavin deficiency can result in a significant clinical phenotype when combined with inborn genetic disturbances or environmental and physiological factors like infections, exercise, diet, aging and pregnancy. Riboflavin, and more importantly its derivatives, flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), play a crucial role in essential cellular processes including mitochondrial energy metabolism, stress responses, vitamin and cofactor biogenesis, where they function as cofactors to ensure the catalytic activity and folding/stability of flavoenzymes. Numerous inborn errors of flavin metabolism and flavoenzyme function have been described, and supplementation with riboflavin has in many cases been shown to be lifesaving or to mitigate symptoms.