Christianity in Latvia in the Twentieth Century Liva Fokrote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

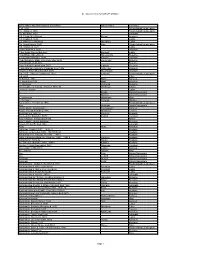

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations His Holiness Patriarch Kirill meets with President of the Latvian Republic Valdis Zatlers On 20 December 2010, the Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church met with the President of the Latvian Republic, Valdis Zatlers. The meeting took place at the Patriarch's working residence in Chisty sidestreet, Moscow. The Latvian President was accompanied by his wife Ms. Lilita Zatlers; Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Latvian Republic to the Russian Federation Edgars Skuja; head of the President's Chancery Edgars Rinkevichs; state secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Andris Teikmanis; Riga Mayor Nil Ushakov; foreign relations advisor to the President, Andris Pelsh; and advisor to the President, Vasily Melnik. Taking part in the meeting were also Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate's Department for External Church Relations; Metropolitan Alexander of Riga and All Lat via; and Bishop Alexander of Daugavpils. Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Russian Federation to the Latvian Republic A. Veshnyakov and the third secretary of the Second European Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs S. Abramkin represented the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia cordially greeted the President of Latvia and his suite, expressing his hope for the first visit of Valdis Zatlers to Moscow to serve to the strengthening of friendly relations between people of the two countries. His Holiness noted with appreciation the high level of relations between the Latvian Republic and the Russian Orthodox Church. "It is an encouraging fact that the Law on the Latvian Orthodox Church has come into force in Latvia in 2008. -

A Statement on Religious Freedom in Eastern Europe an the Soviet Union

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 9 Issue 4 Article 2 7-1989 A Word of Solidarity, A Call for Justice: A Statement on Religious Freedom in Eastern Europe an the Soviet Union Unknown Authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Authors, Unknown (1989) "A Word of Solidarity, A Call for Justice: A Statement on Religious Freedom in Eastern Europe an the Soviet Union," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 9 : Iss. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol9/iss4/2 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A WORD OF SOLIDARITY, A CALL FOR JUSTICE: A STATEMENT ON RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN EASTERN EUROPE AND THE SOVIET UNION United States Catholic Conference November 17, 1988 The Church in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union today is a church of many realities. There is the particularly tragic memory of Bishop Ernest Coba of Albania, murdered by prison authorities for celebrating a Mass with a few other inmates in his cell in contravention of prison regulations on Easter Day, 1979. In Czechoslovakia in 1988 there is the case of Augustin Navratil, a Catholic layman and father of nine, who has been involuntarily committed to a psychiatric clinic for responding to newspaper criticisms of his widely supported 31-point petition for religious rights. -

The Chronicle Henry of Livonia

THE CHRONICLE of HENRY OF LIVONIA HENRICUS LETTUS TRANSLATED WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY James A. Brundage � COLUMBIA UNIVERSI'IY PRESS NEW YORK Columbia University Press RECORDS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION is a series published under the aus Publishers Since 1893 pices of the InterdepartmentalCommittee on Medieval and Renaissance New York Chichester,West Sussex Studies of the Columbia University Graduate School. The Western Records are, in fact, a new incarnation of a venerable series, the Co Copyright© University ofWisconsin Press, 1961 lumbia Records of Civilization, which, for more than half a century, New introduction,notes, and bibliography© 2003 Columbia University Press published sources and studies concerning great literary and historical All rights reserved landmarks. Many of the volumes of that series retain value, especially for their translations into English of primary sources, and the Medieval and Renaissance Studies Committee is pleased to cooperate with Co Library of Congress Cataloging-in-PublicationData lumbia University Press in reissuing a selection of those works in pa Henricus, de Lettis, ca. II 87-ca. 12 59. perback editions, especially suited for classroom use, and in limited [Origines Livoniae sacrae et civilis. English] clothbound editions. The chronicle of Henry of Livonia / Henricus Lettus ; translatedwith a new introduction and notes by James A. Brundage. Committee for the Records of Western Civilization p. cm. - (Records of Western civilization) Originally published: Madison : University of Wisconsin Press, 1961. Caroline Walker Bynum With new introd. Joan M. Ferrante Includes bibliographical references and index. CarmelaVircillo Franklin Robert Hanning ISBN 978-0-231-12888-9 (cloth: alk. paper)---ISBN 978-0-231-12889-6 (pbk.: alk. -

The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 "An Instrument for Awakening": The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission Scott Edward Atwood College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Atwood, Scott Edward, ""An Instrument for Awakening": The Moravian Church and the White River Indian Mission" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625693. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5mtt-7p05 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "AN INSTRUMENT FOR AWAKENING": THE MORAVIAN CHURCH AND THE WHITE RIVER INDIAN MISSION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements-for the Degree of Master of Arts by Scott Edward Atwood 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 1991 <^4*«9_^x .UU James Axtell Michael McGiffert Thaddeus W. Tate, Jr. i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................. -

Catholic N Ewspa Per in Continuous Publication Friday, January 21, 1983 Naming Latvian a Cardinal Called

O OD Inside storal d raft an alysis zpa l statem ents, U .S. draft show consistency, says archbishop o to reducing armaments. NNETH J. DOYLE special committee of U.S. bishops visit to Rome for meetings Jan. 18- statements indicates that on the CO H drafting the document. 19 with Vatican officials and two basic points of the American If anything, the papal thinking -c H •< draft there is a meeting of the seems in certain respects to lean > CO i CITY (NC) — “If anyone thinks that the draft delegations of several European esignate Joseph is off the papal mark, I would hierarchies to discuss the draft minds. toward greater restrictions invite the person to show us document. These two points are: regarding nuclear issues than the CD f Chicago expresses American draft. 3D his work when asked where,” says Archbishop The archbishop’s confidence is • Acceptance of the just war to > can thinks of the U .S. Bernardin when questioned about supported by the text of the draft theory coupled with the belief that The draft of the U.S. bishops fNJ X t pastoral on nuclear criticisms that the U.S. bishops' pastoral which shows a striking the theory virtually negates use of recognizes the validity of the just draft is incompatible with papal consistency with statements by nuclear weapons. war theory, even in today’s an input has been thinking. Pope John Paul II. • The acceptability of nuclear nuclear age. It describes that ositive and suppor- Archbishop Bernardin was A study of the d ra ft in deterrence but only coupled to theory and the moral choice of e man who heads the interviewed by NC News during a juxtaposition with papal strong bilateral efforts at (Continued on page 2) Pennsylvania's P riest dies largest weekly Fr. -

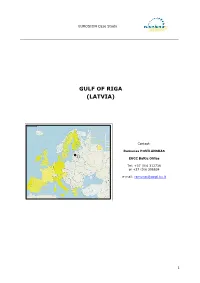

Gulf of Riga (Latvia)

EUROSION Case Study GULF OF RIGA (LATVIA) Contact: Ramunas POVILANSKAS 31 EUCC Baltic Office Tel: +37 (0)6 312739 or +37 (0)6 398834 e-mail: [email protected] 1 EUROSION Case Study 1. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA The length of the Latvian coastline along the Baltic proper and the Gulf of Riga is 496 km. Circa 123 km of the coastline is affected by erosion. The case area ‘Gulf of Riga’ focuses on coastal development within the Riga metropolitan area, which includes the coastal zone of two urban municipalities (pilsetas) – Riga and Jurmala (Figure 1). Riga is the capital city of Latvia. It is located along the lower stream and the mouth of the Daugava river. Its several districts (Bulli, Daugavgriva, Bolderaja, Vecdaugava, Mangali and Vecaki) lie in the deltas of Daugava and Lielupe rivers and on the Gulf of Riga coast. Jurmala municipality is adjacent to Riga from the west. It stretches ca. 30 km along the Gulf of Riga. It is the largest Latvian and Eastern Baltic seaside resort. 1.1 Physical process level 1.1.1 Classification According to the coastal typology adopted for the EUROSION project, the case study area can be described as: 3b. Wave-dominated sediment. Plains. Microtidal river delta. Within this major coastal type several coastal formations and habitats occur, including the river delta and sandy beaches with bare and vegetated sand dunes. Fig. 1: Location of the case study area. 1.1.2 Geology Recent geological history of the case area since the end of the latest Ice Age (ca. -

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

The Courlander Experience in Tobago

THE COURLANDER EXPERIENCE IN TOBAGO THE REPUBLIC OF LATVIA: A maritime nation on the Baltic sea with excellent ports, 64.589km2 in area and a population of nearly 2.000.000 inhabitants. There are apx. 1.500.000 Latvians living in Latvia and the rest of the world. 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of Latvia. COURLANDERS: Latvians from the province of Courland (Kurzeme). In the days of the Duchy of Courland and Semgallia, a “Courlander” could also be an inhabitant of the province of Semgallia. “Courlander” is a literal translation of the Latvian kurzemnieks. The academic word for anything pertaining to Courland is Couronian. THE DUCHY OF COURLAND AND SEMGALLIA: A de facto independent nation formed in 1561 and existing until 1795, comprised of 2 modern day provinces of Latvia, and ruled by the German-Baltic dukes of Courland, although officially a part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The flags of Courland consisted of a red and white 2 band flag and the red and black “crab” flag which originated in Tobago, as there are no crabs of this type in Latvia. As such, it can be considered the first flag of Tobago. CHRONOLOGY 1639 Sent by Duke Jacob, probably involuntarily, 212 Courlanders arrive in Tobago. Unprepared for tropical conditions, they eventually perish. 1642 (possibly 1640) Duke Jacob engages a Brazilian, capt. Cornelis Caroon (later, Caron) to lead a colony comprised basically of Dutch Zealanders, that probably establishes itself in the flat, southwestern portion of the island. Under attack by the Caribs, 70 remaining members of the original 310 colonists are evacuated to Pomeron, Guyana, by the Arawaks. -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 76:1-2 Januaryj April 2012 Table of Contents What Would Bach Do Today? Paul J. Grilne ........................................................................................... 3 Standing on the Brink of the J01'dan: Eschatological Intention in Deute1'onomy Geoffrey R. Boyle .................................................................................. 19 Ch1'ist's Coming and the ChUl'ch's Mission in 1 Thessalonians Charles A. Gieschen ............................................................................. 37 Luke and the Foundations of the Chu1'ch Pete1' J. Scaer .......................................................................................... 57 The Refonnation and the Invention of History Korey D. Maas ...................................................................................... 73 The Divine Game: Faith and the Reconciliation of Opposites in Luthe1"s Lectures on Genesis S.J. Munson ............................................................................................ 89 Fides Heroica? Luthe1" s P1'aye1' fo1' Melanchthon's Recovery f1'om Illness in 1540 Albert B. Collver III ............................................................................ 117 The Quest fo1' Luthe1'an Identity in the Russian Empire Darius Petkiinas .................................................................................. 129 The Theology of Stanley Hauerwas Joel D. Lehenbauer ............................................................................. 157 Theological Observer -

Canon Law of Eastern Churches

KB- KBZ Religious Legal Systems KBR-KBX Law of Christian Denominations KBR History of Canon Law KBS Canon Law of Eastern Churches Class here works on Eastern canon law in general, and further, on the law governing the Orthodox Eastern Church, the East Syrian Churches, and the pre- Chalcedonean Churches For canon law of Eastern Rite Churches in Communion with the Holy See of Rome, see KBT Bibliography Including international and national bibliography 3 General bibliography 7 Personal bibliography. Writers on canon law. Canonists (Collective or individual) Periodicals, see KB46-67 (Christian legal periodicals) For periodicals (Collective and general), see BX100 For periodicals of a particular church, see that church in BX, e.g. BX120, Armenian Church For periodicals of the local government of a church, see that church in KBS Annuals. Yearbooks, see BX100 Official gazettes, see the particular church in KBS Official acts. Documents For acts and documents of a particular church, see that church in KBS, e.g. KBS465, Russian Orthodox Church Collections. Compilations. Selections For sources before 1054 (Great Schism), see KBR195+ For sources from ca.1054 on, see KBS270-300 For canonical collections of early councils and synods, both ecumenical/general and provincial, see KBR205+ For document collections of episcopal councils/synods and diocesan councils and synods (Collected and individual), see the church in KBS 30.5 Indexes. Registers. Digests 31 General and comprehensive) Including councils and synods 42 Decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts (Collective) Including related materials For decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts of a particular church, see that church in KBS Encyclopedias. -

Evidence of the Reformation and Confessionalization Period in Livonian Art

Ojārs Spārītis EVIDENCE OF THE REFORMATION AND CONFESSIONALIZATION PerIOD IN LIVONIAN ArT INTRODUCTION The singular transitional period that led from the slowly evolving me- dieval vision of the world to a new perception of life with its dynamic expression in works of history and art history texts has been given labels that reflect its chronological evolution, as well as the epithets referring to its philosophical and aesthetic content. To illustrate the variety of the social and spiritual aspects of European spiritual life in the second half of the 15th and the 16th century, literature in the humanitarian spheres exploited concepts from the Renaissance, the Reformation and Counter- Reformation. Concepts of both humanism and hedonism were used to characterize the domestic cultural content and form. However, they fail to reveal the development of the new historical period and contradic- tion-rich diversity of the material and spiritual life in the 15th and 16th centuries, when the growing dominance of economic expansion and the endeavours to acquire new knowledge along with the awareness of the tangible benefits and spiritual advantages of a university education was so characteristic of European culture. The history of spiritual evolution, with the variations related to the Reformation and confessionalization, is characterised by local regional contexts and forms of expression, but it also has a mandatory syn- chronicity with the processes of European political and intellectual life. Looking forward to the 500th anniversary of the Reformation initi- DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/BJAH.2015.9.03 24 Ojārs Spārītis Reformation and Confessionalization Period in Livonian Art 25 ated by Martin Luther, it is worth examining the Renaissance-marked – the Teutonic Order and the bishops – used both political and spiritual fine arts testimonies from the central part of the Livonian confedera- methods in their battle for economic power in Riga.