Boris Yeltsin's Foreign Policy Legacy Robert H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Číslo Ke Stažení V

Knihovna města Petřvald Foto Monika Molinková 4 MĚSÍČNÍK PRO KNIHOVNY Cena 40 Kč * * OBSAH MĚSÍČNÍK PRO KNIHOVNY 4 2015 ročník 67 FROM THE CONTENTS 123 ..... * TOPIC: National Digital Library – under the lid Luděk Tichý |123 * INTERVIEW with Vlastimil Vondruška, Czech writer and historian: 1 Pod pokličkou Národní digitální knihovny Vydává: “Books are written to please the readers, not the critics…” * Luděk Tichý Středočeská vědecká knihovna v Kladně, Lenka Šimková, Zuzana Mračková |125 příspěvková organizace Středočeského kraje, ..... * Klára’s cookbook or Ten recipes for library workshops: 125 ul. Generála Klapálka 1641, 272 01 Kladno „Knihy se nepíšou proto, aby se líbily literárním Non-fiction in museum sauce Klára Smolíková |129 * REVIEW: How philosopher Horáček came to Paseka publishers kritikům, ale čtenářům…“ Evid. č. časopisu MK ČR E 485 and what came of it Petr Nagy |131 * Lenka Šimková, Zuzana Mračková ISSN 0011-2321 (Print) ISSN 1805-4064 (Online) * INTERVIEW with PhDr. Dana Kalinová, World of Books Director: Šéfredaktorka: Mgr. Lenka Šimková Choosing from the range will be difficult again… Olga Vašková |133 ..... 129 Redaktorka: Bc. Zuzana Mračková * The future of public libraries in the Czech Republic in terms Grafická úprava a sazba: Kateřina Bobková of changes to the pensions system and social dialogue Poučné knížky v muzejní omáčce * Klára Smolíková Renáta Salátová |135 Sídlo redakce (příjem inzerce a objednávky na předplatné): * FROM ABROAD: The road to Latvia or Observations 131 ..... Středočeská vědecká knihovna v Kladně, from the Di-Xl conference Petr Schink |138 Kterak filozof Horáček k nakladatelství Paseka příspěvková organizace, Gen. Klapálka 1641, 272 01 Kladno * The world seen very slowly by Jan Drda Naděžda Čížková |142 přišel a co z toho vzešlo * Petr Nagy Tel.: 312 813 154 (Lenka Šimková) * FROM THE TREASURES… of the West Bohemian Museum Library Tel.: 312 813 138 (Bc. -

The Russia You Never Met

The Russia You Never Met MATT BIVENS AND JONAS BERNSTEIN fter staggering to reelection in summer 1996, President Boris Yeltsin A announced what had long been obvious: that he had a bad heart and needed surgery. Then he disappeared from view, leaving his prime minister, Viktor Cher- nomyrdin, and his chief of staff, Anatoly Chubais, to mind the Kremlin. For the next few months, Russians would tune in the morning news to learn if the presi- dent was still alive. Evenings they would tune in Chubais and Chernomyrdin to hear about a national emergency—no one was paying their taxes. Summer turned to autumn, but as Yeltsin’s by-pass operation approached, strange things began to happen. Chubais and Chernomyrdin suddenly announced the creation of a new body, the Cheka, to help the government collect taxes. In Lenin’s day, the Cheka was the secret police force—the forerunner of the KGB— that, among other things, forcibly wrested food and money from the peasantry and drove some of them into collective farms or concentration camps. Chubais made no apologies, saying that he had chosen such a historically weighted name to communicate the seriousness of the tax emergency.1 Western governments nod- ded their collective heads in solemn agreement. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both confirmed that Russia was experiencing a tax collec- tion emergency and insisted that serious steps be taken.2 Never mind that the Russian government had been granting enormous tax breaks to the politically connected, including billions to Chernomyrdin’s favorite, Gazprom, the natural gas monopoly,3 and around $1 billion to Chubais’s favorite, Uneximbank,4 never mind the horrendous corruption that had been bleeding the treasury dry for years, or the nihilistic and pointless (and expensive) destruction of Chechnya. -

Russia: CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 to FEBRUARY 1995

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper RUSSIA CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 TO FEBRUARY 1995 July 1995 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures Political Leaders 1. INTRODUCTION 2. CHRONOLOGY 1993 1994 1995 3. APPENDICES TABLE 1: SEAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE STATE DUMA TABLE 2: REPUBLICS AND REGIONS OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION MAP 1: RUSSIA 1 of 58 9/17/2013 9:13 AM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... MAP 2: THE NORTH CAUCASUS NOTES ON SELECTED SOURCES REFERENCES GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures [This glossary is included for easy reference to organizations which either appear more than once in the text of the chronology or which are known to have been formed in the period covered by the chronology. The list is not exhaustive.] All-Russia Democratic Alternative Party. Established in February 1995 by Grigorii Yavlinsky.( OMRI 15 Feb. -

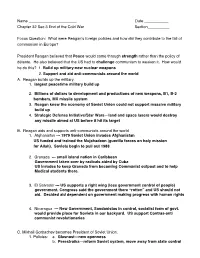

Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section___Focus Question

Name ______________________ Date ___________ Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section__________ Focus Question: What were Reaganʼs foreign policies and how did they contribute to the fall of communism in Europe? President Reagan believed that Peace would come through strength rather than the policy of détente. He also believed that the US had to challenge communism to weaken it. How would he do this? 1. Build up military-new nuclear weapons 2. Support and aid anti-communists around the world A. Reagan builds up the military. 1. largest peacetime military build up 2. Billions of dollars to development and productions of new weapons, B1, B-2 bombers, MX missile system 3. Reagan knew the economy of Soviet Union could not support massive military build up 4. Strategic Defense Initiative/Star Wars—land and space lasers would destroy any missile aimed at US before it hit its target B. Reagan aids and supports anti-communists around the world 1. Afghanistan --- 1979 Soviet Union invades Afghanistan US funded and trained the Mujahadeen (guerilla forces on holy mission for Allah). Soviets begin to pull out 1988 2. Grenada --- small island nation in Caribbean Government taken over by radicals aided by Cuba US invades to keep Granada from becoming Communist outpost and to help Medical students there. 3. El Salvador --- US supports a right wing (less government control of people) government. Congress said the government there “rotten” and US should not aid. Decided aid dependent on government making progress with human rights 4. Nicaragua --- New Government, Sandanistas in control, socialist form of govt. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Russian Conventional Armed Forces: on the Verge of Collapse?

Order Code 97-820 F CRS Issue Brief for Congress Received through the CRS Web Russian Conventional Armed Forces: On the Verge of Collapse? September 4, 1997 (name redacted) Specialist in Russian Affairs Foreign Affairs and National Defense Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Russian Conventional Armed Forces: On the Verge of Collapse? Summary All quantitative indicators show a sharp, and in most cases an accelerating, decline in the size of the Russian armed forces. Since 1986, Russian military manpower has decreased by over 70 percent; tanks and other armored vehicles by two-thirds; and artillery, combat aircraft, and surface warships by one-third. Weapons procurement has been plummeting for over a decade. In some key categories, such as aircraft, tanks, and surface warships, procurement has virtually stopped. This has led not only to a decline in present inventory, but implies a long-term crisis of bloc obsolescence in the future. Russian Government decisions and the budget deficit crisis have hit the Ministry of Defense very hard, cutting defense spending drastically and transforming the Defense Ministry into a residual claimant on scarce resources. Many experts believe that if these budgetary constraints continue for 2-3 more years, they must lead either to more drastic force reductions or to military collapse. Military capabilities are also in decline. Reportedly, few, if any, of Russia’s army divisions are combat-ready. Field exercises, flight training, and out-of-area naval deployments have been sharply reduced. Morale is low, partly because of non-payment of servicemen’s salaries. Draft evasion and desertion are rising. -

Yeltsin's Winning Campaigns

7 Yeltsin’s Winning Campaigns Down with Privileges and Out of the USSR, 1989–91 The heresthetical maneuver that launched Yeltsin to the apex of power in Russia is a classic representation of Riker’s argument. Yeltsin reformulated Russia’s central problem, offered a radically new solution through a unique combination of issues, and engaged in an uncompro- mising, negative campaign against his political opponents. This allowed Yeltsin to form an unusual coalition of different stripes and ideologies that resulted in his election as Russia’s ‹rst president. His rise to power, while certainly facilitated by favorable timing, should also be credited to his own political skill and strategic choices. In addition to the institutional reforms introduced at the June party conference, the summer of 1988 was marked by two other signi‹cant developments in Soviet politics. In August, Gorbachev presented a draft plan for the radical reorganization of the Secretariat, which was to be replaced by six commissions, each dealing with a speci‹c policy area. The Politburo’s adoption of this plan in September was a major politi- cal blow for Ligachev, who had used the Secretariat as his principal power base. Once viewed as the second most powerful man in the party, Ligachev now found himself chairman of the CC commission on agriculture, a position with little real in›uence.1 His ideological portfo- lio was transferred to Gorbachev’s ally, Vadim Medvedev, who 225 226 The Strategy of Campaigning belonged to the new group of soft-line reformers. His colleague Alexan- der Yakovlev assumed responsibility for foreign policy. -

The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Michael P

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 28 Article 2 Issue 1 Winter 1995 Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Michael P. Scharf Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Scharf, Michael P. (1995) "Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol28/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Michael P. Scharf * Musical Chairs: The Dissolution of States and Membership in the United Nations Introduction .................................................... 30 1. Background .............................................. 31 A. The U.N. Charter .................................... 31 B. Historical Precedent .................................. 33 C. Legal Doctrine ....................................... 41 I. When Russia Came Knocking- Succession to the Soviet Seat ..................................................... 43 A. History: The Empire Crumbles ....................... 43 B. Russia Assumes the Soviet Seat ........................ 46 C. Political Backdrop .................................... 47 D. -

Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia's Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 64 Number 1 Internationalism and Sovereignty Article 3 (Fall 2019) 4-23-2020 Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine. Igor Gretskiy [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Igor Gretskiy, Lukyanov Doctrine: Conceptual Origins of Russia’s Hybrid Foreign Policy—The Case of Ukraine., 64 St. Louis U. L.J. (2020). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol64/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW LUKYANOV DOCTRINE: CONCEPTUAL ORIGINS OF RUSSIA’S HYBRID FOREIGN POLICY—THE CASE OF UKRAINE. IGOR GRETSKIY* Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kremlin’s assertiveness and unpredictability on the international arena has always provoked enormous attention to its foreign policy tools and tactics. Although there was no shortage of publications on topics related to different aspects of Moscow’s foreign policy varying from non-proliferation of nuclear weapons to soft power diplomacy, Russian studies as a discipline found itself deadlocked within the limited number of old dichotomies, (e.g., West/non-West, authoritarianism/democracy, Europe/non-Europe), initially proposed to understand the logic of Russia’s domestic and foreign policy transformations.1 Furthermore, as the decision- making process in Moscow was getting further from being transparent due to the increasingly centralized character of its political system, the emergence of new theoretical frameworks with greater explanatory power was an even more difficult task. -

The Russian Vertikal: the Tandem, Power and the Elections

Russia and Eurasia Programme Paper REP 2011/01 The Russian Vertikal: the Tandem, Power and the Elections Andrew Monaghan Nato Defence College June 2011 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/ speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication. REP Programme Paper. The Russian Vertikal: the Tandem, Power and the Elections Introduction From among many important potential questions about developments in Russian politics and in Russia more broadly, one has emerged to dominate public policy and media discussion: who will be Russian president in 2012? This is the central point from which a series of other questions and debates cascade – the extent of differences between President Dmitry Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin and how long their ‘Tandem’ can last, whether the presidential election campaign has already begun and whether they will run against each other being only the most prominent. Such questions are typically debated against a wider conceptual canvas – the prospects for change in Russia. Some believe that 2012 offers a potential turning point for Russia and its relations with the international community: leading to either the return of a more ‘reactionary’ Putin to the Kremlin, and the maintenance of ‘stability’, or another term for the more ‘modernizing’ and ‘liberal’ Medvedev. -

Democratizing Communist Militaries

Democratizing Communist Militaries Democratizing Communist Militaries The Cases of the Czech and Russian Armed Forces Marybeth Peterson Ulrich Ann Arbor To Mark, Erin, and Benjamin Copyright © by the University of Michigan 1999 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America V∞ Printed on acid-free paper 2002 2001 2000 1999 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ulrich, Marybeth Peterson. Democratizing Communist militaries : the cases of the Czech and Russian armed forces / Marybeth Peterson Ulrich. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-472-10969-3 (acid-free paper) 1. Civil-military relations—Russia (Federation) 2. Civil-military relations—Former Soviet republics. 3. Civil-military relations—Czech Republic. 4. Russia (Federation)—Armed Forces—Political activity. 5. Former Soviet republics—Armed Forces—Political activity. 6. Czech Republic—Armed Forces—Political activity. 7. Military assistance, American—Russia (Federation) 8. Military assistance, American—Former Soviet republics. 9. Military assistance, American—Czech Republic. I. Title. JN6520.C58 U45 1999 3229.5909437109049—dc21 99-6461 CIP Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgments ix List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1. A Theory of Democratic Civil-Military Relations in Postcommunist States 5 Chapter 2. A Survey of Overall U.S. -

The City of Moscow in Russia's Foreign and Security Policy: Role

Eidgenössische “Regionalization of Russian Foreign and Security Policy” Technische Hochschule Zürich Project organized by The Russian Study Group at the Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research Andreas Wenger, Jeronim Perovic,´ Andrei Makarychev, Oleg Alexandrov WORKING PAPER NO.7 APRIL 2001 The City of Moscow in Russia’s Foreign and Security Policy: Role, Aims and Motivations DESIGN : SUSANA PERROTTET RIOS Moscow enjoys an exceptional position among the Russian regions. Due to its huge By Oleg B. Alexandrov economic and financial potential, the city of Moscow largely shapes the country’s economic and political processes. This study provides an overall insight into the complex international network that the city of Moscow is tied into. It also assesses the role, aims and motivations of the main regional actors that are involved. These include the political authorities, the media tycoons and the major financial-industrial groups. Special attention is paid to the problem of institutional and non-institutional interaction between the Moscow city authorities and the federal center in the foreign and security policy sector, with an emphasis on the impact of Putin’s federal reforms. Contact: Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research ETH Zentrum / SEI CH-8092 Zürich Switzerland Andreas Wenger, head of project [email protected] Jeronim Perovic´ , project coordinator [email protected] Oleg Alexandrov [email protected]; [email protected] Andrei Makarychev [email protected]; [email protected] Order of copies: Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research ETH Zentrum / SEI CH-8092 Zürich Switzerland [email protected] Papers available in full-text format at: http://www.fsk.ethz.ch/ Layout by Marco Zanoli The City of Moscow in Russia’s Foreign and Security Policy: Role, Aims and Motivations By Oleg B.