Chronic Food Poverty in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follow the Money: the Philippines

A Rapid Assessment of Gold and Financial Flows linked to Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in the Philippines FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES October 2017 PB FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES i ii FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES iii A Rapid Assessment of Gold and Financial Flows linked to Artis- anal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in the Philippines FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES October 2017 ii FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES iii © UNIDO 2017. All rights reserved. This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” or “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. Unless otherwise mentioned, all references to sums of money are given in United States dollars. References to “tons” are to metric tons, unless otherwise stated. All photos © UNIDO unless otherwise stated iv FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES FOLLOW THE MONEY: THE PHILIPPINES v Acknowledgments This report was authored by Marcena Hunter and Laura Adal of the Global Initiative against Transnational Orga- nized Crime. -

Hiv/Aids & Art Registry of the Philippines

Department of Health | Epidemiology Bureau HIV/AIDS & ART REGISTRY OF THE PHILIPPINES AUGUST 2018 Average number of people newly diagnosed with HIV per day, selected years 2009 2011 2013 2015 2018 2 7 13 22 31 NEWLY DIAGNOSED HIV CASES In August 2018, there were 1,047 new HIV antibody Table 1. Summary of HIV diagnoses and deaths seropositive individuals reported to the HIV/AIDS & ART Demographic Data Aug 2018 Jan - Aug Jan 2013– Jan 1984 Registry of the Philippines (HARP) [Table 1]. Seventeen 2018 Aug 2018 -Aug 2018 percent (176) had clinical manifestations of advanced HIV Total reported cases 1,047 7,579 46,509 58,181 infection (WHO clinical stage 3 or 4) at the time of diagnosis. With advanced infectiona 176 1,341 5,244 6,409 Ninety-five percent (998) of the newly diagnosed were male. Male 998 7,168 44,380 54,421b The median age was 28 years old (age range: 15 - 61 years old). More than half of the cases (51%, 537) were 25-34 years Female 49 411 2,129 3,749b old and 30% (309) were 15-24 years old at the time of Age Range (Median) 15-61 (28) 1-73 (28) 1-82 (28) 1-82 (28)c testing. c Age groups: <15 y/o 0 13 100 162 One third (31%, 328) were from the National Capital Region 15-24 y/o 309 2,234 13,571 16,383c (NCR). Region 4A (17%, 173 cases), Region 3 (11%, 119), 25-34 y/o 537 3,852 24,177 29,740c Region 7 (10%, 108), and Region 6 (6%, 58), round off the 35-49 y/o 179 1,292 7,592 10,285c top five regions with the most number of newly diagnosed cases for the month, together accounting for 75% of the total 50 y/o & above 22 188 1,069 1,538c [Figure 2]. -

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines November 2005 Republika ng Pilipinas PAMBANSANG LUPON SA UGNAYANG PANG-ESTADISTIKA (NATIONAL STATISTICAL COORDINATION BOARD) http://www.nscb.gov.ph in cooperation with The WORLD BANK Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines FOREWORD This report is part of the output of the Poverty Mapping Project implemented by the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) with funding assistance from the World Bank ASEM Trust Fund. The methodology employed in the project combined the 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES), 2000 Labor Force Survey (LFS) and 2000 Census of Population and Housing (CPH) to estimate poverty incidence, poverty gap, and poverty severity for the provincial and municipal levels. We acknowledge with thanks the valuable assistance provided by the Project Consultants, Dr. Stephen Haslett and Dr. Geoffrey Jones of the Statistics Research and Consulting Centre, Massey University, New Zealand. Ms. Caridad Araujo, for the assistance in the preliminary preparations for the project; and Dr. Peter Lanjouw of the World Bank for the continued support. The Project Consultants prepared Chapters 1 to 8 of the report with Mr. Joseph M. Addawe, Rey Angelo Millendez, and Amando Patio, Jr. of the NSCB Poverty Team, assisting in the data preparation and modeling. Chapters 9 to 11 were prepared mainly by the NSCB Project Staff after conducting validation workshops in selected provinces of the country and the project’s national dissemination forum. It is hoped that the results of this project will help local communities and policy makers in the formulation of appropriate programs and improvements in the targeting schemes aimed at reducing poverty. -

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018 Head Office Project Contractor Amount of Project Date of NOA Date of Contract Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 27-Nov-19 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of JARZOE Builders, Inc./ DALEBO Construction and General. 328,013,357.76 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Estancia, Iloilo; Culasi, Roxas City; and Dumaguit, New Washington, Aklan Merchandise/JV Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of Lipata, Goldridge Construction & Development Corporation / JARZOE 200,000,842.41 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Culasi, Antique; San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Sibunag, Guimaras Builders, Inc/JV Consultancy Services for the Conduct of Feasibility Studies and Formulation of Master Plans at Science & Vision for Technology, Inc./ Syconsult, INC./JV 26,046,800.00 12-Nov-19 16-Dec-19 Selected Ports Davila Port Development Project, Port of Davila, Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte RCE Global Construction, Inc. 103,511,759.47 24-Oct-19 09-Dec-19 Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Rehabilitation of Existing RC Pier, Port of Baybay, Leyte A. -

Rapid Market Appraisal for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao Del Sur (Brackishwater Areas)

Rapid Market Appraisal for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) AMC MINI PROJECT: TEAM TILAPIA Acuna, Thaddeus R., UP Mindanao Almazan, Cynthia V., DOST-PCAARRD Castillo, Monica, DOST-PCAARRD Romo, Glory Dee A., UP Mindanao Rosetes, Mercy A., Foodlink Advocacy Co-operative (FAC) RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) OBJECTIVE To conduct a market assessment of expanding areas for tilapia culture production in costal and brackishwater areas in the province of Davao del Sur. RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) RESEARCH QUESTIONS 1. Does consumption level of Tilapia a key contributing factor for potential expansion of Tilapia production in Davao del Sur? 2. Is the market potential of competitiveness of Tilapia substantial enough to revitalize tilapia production in Davao del Sur? RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) METHODOLOGY RAPID APPRAISAL APPROACH Secondary data Encoding Market Areas for gathering Constraints Intervention Primary data Market gathering Competitiveness * KIs Market * Market Mapping Opportunities * Market Visits A Step-by step approach of Rapid Market Appraisal (Adapted from the RMA proposal for underutilized fruits) RMA for Expanding Tilapia Culture Areas in Davao del Sur (brackishwater areas) INDUSTRY SITUATION ✓ Tilapia is a major aquaculture product in the Philippines that is considered important to the country’s food security and nutrition (Perez, 2017) ✓ Most -

Energy Consumption, Weather Variability, and Gender in the Philippines: a Discrete/Continuous Approach Connie Bayudan-Dacuycuy

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Energy Consumption, Weather Variability, and Gender in the Philippines: A Discrete/Continuous Approach Connie Bayudan-Dacuycuy DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2017-06 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are being circulated in a limited number of copies only for purposes of soliciting comments and suggestions for further refinements. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. March 2017 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 18th Floor, Three Cyberpod Centris – North Tower, EDSA corner Quezon Avenue, 1100 Quezon City, Philippines Tel Nos: (63-2) 3721291 and 3721292; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph Energy consumption, weather variability and gender in the Philippines: A discrete/continuous approach Connie Bayudan-Dacuycuy1 Using a discrete/continuous modeling approach, this paper analyzes energy use and consumption in the Philippines within the context of weather variability and gender. Consistent with energy stacking strategy where households use a combination of traditional and modern energy sources, this paper finds that households use multiple energy sources in different weather fluctuation scenarios. It also finds that weather variability has the highest effects on the electricity consumption of balanced and female-majority households that are female headed and in rural areas. -

PHL-OCHA-R11 Profile-A3

Philippines: Region XI (Davao) Profile Region XI (Davao) is located in the southeastern POPULATION POVERTY portion of the island of Mindanao surrounding the Davao Gulf. Source: PSA 2010 Census Source: PSA 2016 It is bordered to the north by the provinces of Surigao del Sur, 5 6 43 1,162 Region XI population Region XI households 2.39M Poverty incidence among population (%) Agusan del Sur, and Bukidnon, on the east by the Philippine PROVINCES CITIES MUNICIPALITIES BARANGAYS Sea, and on the west by the Central Mindanao provinces. 4.89 1.18 48.9% 60% million million 40% 30.7% Female 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 30.6% 31.4% + 6 5 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 9 4 - Population statistics trend - - - - - - - - - - 20% - - 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 6 6 5 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 22.0% Male 0 2006 2009 2012 2015 51.1% 4.89M 4.47M 2015 Census 2010 Census 2.50M % Poverty incidence 0 - 14 15 - 26 27 - 39 40 - 56 57 - 84 DAVAO DEL NORTE NATURAL DISASTERS HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Nabunturan 4,300 Source: OCD/NDRRMC Conditional cash transfer Source: DSWD 117 Number of disaster beneficiaries (children) incidents per year 562,200 272,024 Tagum Affected population 451,700 31 (in thousands) 21 21 24 427,500 219,637 Notable incidents Typhoon 209,688 COMPOSTELA 300,500 Girls Flooding 290,158 232,085 119,200 VALLEY 147,666 248 No affected population 217,764 107,200 2 94 27 due to tropical cyclones in 2015 and 2016 DAVAO ORIENTAL 152,871 Boys Davao City 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2011 2012 2013 2014 Mati DAVAO DEL SUR NUTRITION WATER AND SANITATION HEALTH Source: FNRI 2012 Source: PSA 2010 -

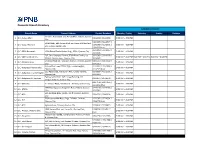

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE Branch Name Present Address Contact Numbers Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday Holidays cor Gen. Araneta St. and Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon 1 Q.C.-Cubao Main 911-2916 / 912-1938 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 912-3070 / 912-2577 / SRMC Bldg., 901 Aurora Blvd. cor Harvard & Stanford 2 Q.C.-Cubao-Harvard 913-1068 / 912-2571 / 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Sts., Cubao, Quezon City 913-4503 (fax) 332-3014 / 332-3067 / 3 Q.C.-EDSA Roosevelt 1024 Global Trade Center Bldg., EDSA, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 332-4446 G/F, One Cyberpod Centris, EDSA Eton Centris, cor. 332-5368 / 332-6258 / 4 Q.C.-EDSA-Eton Centris 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM EDSA & Quezon Ave., Quezon City 332-6665 Elliptical Road cor. Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon 920-3353 / 924-2660 / 5 Q.C.-Elliptical Road 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 924-2663 Aurora Blvd., near PSBA, Brgy. Loyola Heights, 421-2331 / 421-2330 / 6 Q.C.-Katipunan-Aurora Blvd. 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 421-2329 (fax) 335 Agcor Bldg., Katipunan Ave., Loyola Heights, 929-8814 / 433-2021 / 7 Q.C.-Katipunan-Loyola Heights 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 433-2022 February 07, 2014 : G/F, Linear Building, 142 8 Q.C.-Katipunan-St. Ignatius 912-8077 / 912-8078 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Katipunan Road, Quezon City 920-7158 / 920-7165 / 9 Q.C.-Matalino 21 Tempus Bldg., Matalino St., Diliman, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 924-8919 (fax) MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon 927-5443 / 922-3765 / 10 Q.C.-MWSS 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 922-3764 SRA Building, Brgy. -

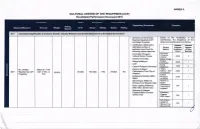

(CCP) Revalidated Performance Scorecard 201 6

ANNEX A GULTURAL CENTER OF THE PHTLTPPTNES (CCP) Revalidated Performance Scorecard 201 6 Component Target Submission GCG Validation Supporting Documents Remarks Rating Objective/Measure Formula Weight 2016 Rating System Actual Rating Actual so1 Contributed Significantly to lnclusive Growth, lndustry Relevant and Socially Responsive to the Global Environment o Summary of 2016 Areas Based on the revalidation of the Reached Quarterly CCP submissions, the breakdown of the Exchange Programs actual accomplishment is as follows: o Certification attesting the Attested Attested estimated number of Partner Estimate Number audience count from the Agency Audience of Sites following partner agencies: Count Reached Koronadal Hinugyaw Koronadal - Hinugyaw 4,500 2 Cultural Dance Troupe, Cultural - Kanami Koronadal, Bulakenyo, - Sining 9,000 1 Koronadal E, - CCP, lu o - Central Philippine University 7,000 2 oJ I - Harana sa Bayan Teatro uJ No. of Sites Below 21 = 0o/o Y '143 Performance Tour (City of Obrero/ CCP 4,500 1 SM1 Reached by CCP (>21x1Oo/o)x 10.00% 30 sites sites 10o/o 24 sites 8o/o oF Programs 100 Angeles) - Kabataang Gitarista (MSU- Philippine 3,100 ,| lligan) - Gift of Music NAMCYA SA Winners Tour (Bacolod City) Bayan Performance Basic Lighting Workshop 350 1 - Tour (City of (MSU-Gen. Santos City) Angeles) - Opening of Kalingan Fesetival (MSU-General Santos City) Gitarista 260 1 (MSU-lligan) NAMCYA 300 1 Winners Tour Bacolod \ cULTURAL CENTER OF THE PHTLTPPTNES (CCP) Validated Performance Scorecard 2016 Basic Lighting Workshop 28 Kalingan 1 Fesetival (MSU- 7000 General o Summary of 2016 Tanghalang 570 3 Accomplishments (Cultural Pilipino Exchange Department) . National Park & . Certification attesting the Developmen estimated number of t Commiftee audience count from the o Philippine following partner agencies: Coast Guard - Koronadal Hinugyaw . -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

PHI-OCHA Logistics Map 04Dec2012

Philippines: TY Bopha (Pablo) Road Matrix l Mindanao Tubay Madrid Cortes 9°10'N Carmen Mindanao Cabadbaran City Lanuza Southern Philippines Tandag City l Region XIII Remedios T. Romualdez (Caraga) Magallanes Region X Region IX 9°N Tago ARMM Sibagat Region XI Carmen (Davao) l Bayabas Nasipit San Miguel l Butuan City Surigao Cagwait Region XII Magsaysay del Sur Buenavista l 8°50'N Agusan del Norte Marihatag Gingoog City l Bayugan City Misamis DAVAO CITY- BUTUAN ROAD Oriental Las Nieves San Agustin DAVAO CITY TAGUM CITY NABUNTURAN MONTEVISTA MONKAYO TRENTO SAN FRANS BUTUAN DAVAO CITY 60km/1hr Prosperidad TAGUM CITY 90km/2hr 30km/1hr NABUNTURAN MONTEVISTA 102km/2.5hr 42km/1.5hr 12km/15mns 8°40'N 120km/2.45hr 60km/1hr 30km/45mns. 18kms/15mns Claveria Lianga MONKAYO 142km/3hr 82km/2.5hr 52km/1.5hr 40km/1hr 22km/30mns Esperanza TRENTO SAN FRANCISCO 200km/4hr 140km/3 hr 110km/2.5hr 98km/2.hr 80km/1.45hr 58km/1.5hr BUTUAN 314km/6hr 254km/5hr 224km/4hr 212km/3.5hr 194km/3hr 172km/2.45hr 114km/2hr l Barobo l 8°30'N San Luis Hinatuan Agusan Tagbina del Sur San Francisco Talacogon Impasug-Ong Rosario 8°20'N La Paz l Malaybalay City l Bislig City Bunawan Loreto 8°10'N l DAVAO CITY TO - LORETO, AGUSAN DEL SUR ROAD DAVAO CITY TAGUM CITY NABUNTURAN TRENTO STA. JOSEFA VERUELA LORETO DAVAO CITY 60km/1hr Lingig TAGUM CITY Cabanglasan Trento 90km/2hr 30km/1hr NABUNTURAN Veruela Santa Josefa TRENTO 142km/3hr 82km/2.5hr 52km/1.5hr STA. -

Republic of the Philippines Province of Antique PROVINCIAL BIDS and AWARDS COMMITTEE for HEALTH San Jose De Buenavista 1 1 Job S

Republic of the Philippines Province of Antique PROVINCIAL BIDS AND AWARDS COMMITTEE FOR HEALTH San Jose de Buenavista NEGOTIATED PROCUREMENT (SMALL VALUE PROCUREMENT ) Standard Form No. SF-GOOD-60 Date: March 31, 2021 Revised on May 24, 2004 RFQ No. DD-2021-03-007 Various Suppliers/Contractors San Jose, Antique/Iloilo City Please quote your lowest price on the item/s listed below, subject to the General Conditions stated herein the shortest time of delivery and submit your quotation duly signed by your representative not later than April 07, 2021 at the Room 2, Second Floor, Provincial Health Office Atabay, San Jose, Antique at 2: 00 o' clock p.m. in the return envelope attached herewith. RIC NOEL A. NACIONGAYO, MD, MPA, FPSMS Provincial Health Officer II/BAC Chairman (Procurement Officer) ITEM BRAND BID QTY UNIT DESCRIPTION UNIT COST TOTAL ABC/UNIT TOTAL BID PRICE NO OFFERED PRICE/UNIT 1 1 job Supply of Labor for Sanitary Clean Up of 150,050.00 150,050.00 various set of septic tank vault of ASMGH. GRAND TOTAL ABC: 150,050.00 TOTAL AMOUNT IN WORDS: GRAND TOTAL BID P TERMS/CONDITIONS AND REQUIREMENTS: 1. WARRANTY SHALL BE FOR A PERIOD OF SIX (6) MONTHS FOR SUPPLIES AND MATERIALS, ONE (1) YEAR FOR EQUIPMENT, FROM DATE OF ACCEPTANCE BY THE PROCURING ENTITY 2. MAYOR'S PERMIT. 3. PhilGEPS REGISTRATION CERTIFICATE SHALL BE ATTACHED UPON SUBMISSION OF THE QUOTATION. 4. BIDDERS SHALL SUBMIT ORIGINAL BROCHURES SHOWING CERTIFICATION OF THE PRODUCT BEING OFFERED 5. OMNIBUS SWORN STATEMENT (COA Circular No. 2012-001 (9.2)) 6.