Energy Consumption, Weather Variability, and Gender in the Philippines: a Discrete/Continuous Approach Connie Bayudan-Dacuycuy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hiv/Aids & Art Registry of the Philippines

Department of Health | Epidemiology Bureau HIV/AIDS & ART REGISTRY OF THE PHILIPPINES AUGUST 2018 Average number of people newly diagnosed with HIV per day, selected years 2009 2011 2013 2015 2018 2 7 13 22 31 NEWLY DIAGNOSED HIV CASES In August 2018, there were 1,047 new HIV antibody Table 1. Summary of HIV diagnoses and deaths seropositive individuals reported to the HIV/AIDS & ART Demographic Data Aug 2018 Jan - Aug Jan 2013– Jan 1984 Registry of the Philippines (HARP) [Table 1]. Seventeen 2018 Aug 2018 -Aug 2018 percent (176) had clinical manifestations of advanced HIV Total reported cases 1,047 7,579 46,509 58,181 infection (WHO clinical stage 3 or 4) at the time of diagnosis. With advanced infectiona 176 1,341 5,244 6,409 Ninety-five percent (998) of the newly diagnosed were male. Male 998 7,168 44,380 54,421b The median age was 28 years old (age range: 15 - 61 years old). More than half of the cases (51%, 537) were 25-34 years Female 49 411 2,129 3,749b old and 30% (309) were 15-24 years old at the time of Age Range (Median) 15-61 (28) 1-73 (28) 1-82 (28) 1-82 (28)c testing. c Age groups: <15 y/o 0 13 100 162 One third (31%, 328) were from the National Capital Region 15-24 y/o 309 2,234 13,571 16,383c (NCR). Region 4A (17%, 173 cases), Region 3 (11%, 119), 25-34 y/o 537 3,852 24,177 29,740c Region 7 (10%, 108), and Region 6 (6%, 58), round off the 35-49 y/o 179 1,292 7,592 10,285c top five regions with the most number of newly diagnosed cases for the month, together accounting for 75% of the total 50 y/o & above 22 188 1,069 1,538c [Figure 2]. -

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018 Head Office Project Contractor Amount of Project Date of NOA Date of Contract Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 27-Nov-19 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of JARZOE Builders, Inc./ DALEBO Construction and General. 328,013,357.76 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Estancia, Iloilo; Culasi, Roxas City; and Dumaguit, New Washington, Aklan Merchandise/JV Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of Lipata, Goldridge Construction & Development Corporation / JARZOE 200,000,842.41 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Culasi, Antique; San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Sibunag, Guimaras Builders, Inc/JV Consultancy Services for the Conduct of Feasibility Studies and Formulation of Master Plans at Science & Vision for Technology, Inc./ Syconsult, INC./JV 26,046,800.00 12-Nov-19 16-Dec-19 Selected Ports Davila Port Development Project, Port of Davila, Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte RCE Global Construction, Inc. 103,511,759.47 24-Oct-19 09-Dec-19 Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Rehabilitation of Existing RC Pier, Port of Baybay, Leyte A. -

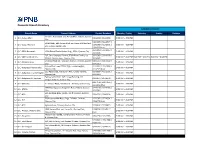

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE Branch Name Present Address Contact Numbers Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday Holidays cor Gen. Araneta St. and Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon 1 Q.C.-Cubao Main 911-2916 / 912-1938 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 912-3070 / 912-2577 / SRMC Bldg., 901 Aurora Blvd. cor Harvard & Stanford 2 Q.C.-Cubao-Harvard 913-1068 / 912-2571 / 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Sts., Cubao, Quezon City 913-4503 (fax) 332-3014 / 332-3067 / 3 Q.C.-EDSA Roosevelt 1024 Global Trade Center Bldg., EDSA, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 332-4446 G/F, One Cyberpod Centris, EDSA Eton Centris, cor. 332-5368 / 332-6258 / 4 Q.C.-EDSA-Eton Centris 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM EDSA & Quezon Ave., Quezon City 332-6665 Elliptical Road cor. Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon 920-3353 / 924-2660 / 5 Q.C.-Elliptical Road 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 924-2663 Aurora Blvd., near PSBA, Brgy. Loyola Heights, 421-2331 / 421-2330 / 6 Q.C.-Katipunan-Aurora Blvd. 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 421-2329 (fax) 335 Agcor Bldg., Katipunan Ave., Loyola Heights, 929-8814 / 433-2021 / 7 Q.C.-Katipunan-Loyola Heights 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 433-2022 February 07, 2014 : G/F, Linear Building, 142 8 Q.C.-Katipunan-St. Ignatius 912-8077 / 912-8078 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Katipunan Road, Quezon City 920-7158 / 920-7165 / 9 Q.C.-Matalino 21 Tempus Bldg., Matalino St., Diliman, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 924-8919 (fax) MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon 927-5443 / 922-3765 / 10 Q.C.-MWSS 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 922-3764 SRA Building, Brgy. -

Republic of the Philippines Province of Antique PROVINCIAL BIDS and AWARDS COMMITTEE for HEALTH San Jose De Buenavista 1 1 Job S

Republic of the Philippines Province of Antique PROVINCIAL BIDS AND AWARDS COMMITTEE FOR HEALTH San Jose de Buenavista NEGOTIATED PROCUREMENT (SMALL VALUE PROCUREMENT ) Standard Form No. SF-GOOD-60 Date: March 31, 2021 Revised on May 24, 2004 RFQ No. DD-2021-03-007 Various Suppliers/Contractors San Jose, Antique/Iloilo City Please quote your lowest price on the item/s listed below, subject to the General Conditions stated herein the shortest time of delivery and submit your quotation duly signed by your representative not later than April 07, 2021 at the Room 2, Second Floor, Provincial Health Office Atabay, San Jose, Antique at 2: 00 o' clock p.m. in the return envelope attached herewith. RIC NOEL A. NACIONGAYO, MD, MPA, FPSMS Provincial Health Officer II/BAC Chairman (Procurement Officer) ITEM BRAND BID QTY UNIT DESCRIPTION UNIT COST TOTAL ABC/UNIT TOTAL BID PRICE NO OFFERED PRICE/UNIT 1 1 job Supply of Labor for Sanitary Clean Up of 150,050.00 150,050.00 various set of septic tank vault of ASMGH. GRAND TOTAL ABC: 150,050.00 TOTAL AMOUNT IN WORDS: GRAND TOTAL BID P TERMS/CONDITIONS AND REQUIREMENTS: 1. WARRANTY SHALL BE FOR A PERIOD OF SIX (6) MONTHS FOR SUPPLIES AND MATERIALS, ONE (1) YEAR FOR EQUIPMENT, FROM DATE OF ACCEPTANCE BY THE PROCURING ENTITY 2. MAYOR'S PERMIT. 3. PhilGEPS REGISTRATION CERTIFICATE SHALL BE ATTACHED UPON SUBMISSION OF THE QUOTATION. 4. BIDDERS SHALL SUBMIT ORIGINAL BROCHURES SHOWING CERTIFICATION OF THE PRODUCT BEING OFFERED 5. OMNIBUS SWORN STATEMENT (COA Circular No. 2012-001 (9.2)) 6. -

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

2017 Aklan Provincial Athletic Meet Calendar of Activities Enclosure No

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Region VI - Western Visayas DIVISION OF AKLAN Kalibo, Aklan September 25,201 DIVISION MEMORANDUM No. .21-7 ' s. 2017 2017 AKLAN PROVINCIAL ATHLETICMEET To: Chief Education Supervisors Education Program Supervisors/Coordinators Public Schools District Supervisors Principals/Head Teacher In-Charge of the District Senior/Education Program Specialists Heads of Public/Private Elementary/Secondary and Integrated Scho 1. Thisisto announce to the field that the schedule of the 2017Aklan Pro incial Athletic Meet will be on November 2 - 6, 2017 at the Aklan Sports Co plex. Calangcang, Makato, Aklan with the theme: "School Sports: Developin Skills, Promoting Peace, Uniting Local and ASEANCommunities." 2. The objectives of the Provincial Meet are to: a. promote physical education and sports as an integral part of the Basic Education for holistic development of the youth to become responsible and globally competitive citizens of the country; b. inculcate the spirit of discipline, teamwork, excellence, fair play, solidarity, sportsmanship, and other values inherent in sports; c. promote and achieve peace through sports; d. widen the base talent identification, selection, recruitment trai ing and exposure of elementary pupils and secondary students as well as Paralympic athletes to seNe as athletes' roster to the Nati nal sports Associations for international competitions; and e. provide a database that will serve as basis to further improve' the school sports development programs. 3. There are six (6) competing units in this year's meet. The competing units are the following: Unit I - Altavas, Batan and New Washington Unit 11 - Bongo, Balete, Libacao and Madalag Unit III - Lezo.Malinao, Makato and Numancia Unit IV- Buruanga, Malay, Nabas and Tangalan Unit V - Kalibo I and Kalibo 11 Unit VI - Ibajay Eastand Ibajay West 4. -

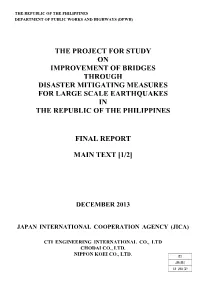

The Project for Study on Improvement of Bridges Through Disaster Mitigating Measures for Large Scale Earthquakes in the Republic of the Philippines

THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS (DPWH) THE PROJECT FOR STUDY ON IMPROVEMENT OF BRIDGES THROUGH DISASTER MITIGATING MEASURES FOR LARGE SCALE EARTHQUAKES IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT MAIN TEXT [1/2] DECEMBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD CHODAI CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. EI JR(先) 13-261(2) Exchange Rate used in the Report is: PHP 1.00 = JPY 2.222 US$ 1.00 = JPY 97.229 = PHP 43.756 (Average Value in August 2013, Central Bank of the Philippines) LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE B : WITHIN METRO MANILA) i LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE C : OUTSIDE METRO MANILA) ii B01 Delpan Bridge B02 Jones Bridge B03 Mc Arthur Bridge B04 Quezon Bridge B05 Ayala Bridge B06 Nagtahan Bridge B07 Pandacan Bridge B08 Lambingan Bridge B09 Makati-Mandaluyong Bridge B10 Guadalupe Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (1/2) iii B11 C-5 Bridge B12 Bambang Bridge B13-1 Vargas Bridge (1 & 2) B14 Rosario Bridge B15 Marcos Bridge B16 Marikina Bridge B17 San Jose Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (2/2) iv C01 Badiwan Bridge C02 Buntun Bridge C03 Lucban Bridge C04 Magapit Bridge C05 Sicsican Bridge C06 Bamban Bridge C07 1st Mandaue-Mactan Bridge C08 Marcelo Fernan Bridge C09 Palanit Bridge C10 Jibatang Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (1/2) v C11 Mawo Bridge C12 Biliran Bridge C13 San Juanico Bridge C14 Lilo-an Bridge C15 Wawa Bridge C16 2nd Magsaysay Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (2/2) vi vii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (1/2) viii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (2/2) ix Perspective View of Guadalupe Bridge x Perspective View of Palanit Bridge xi Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (1/2) xii Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (2/2) xiii Perspective View of Wawa Bridge TABLE OF CONTENTS Location Map Photos Perspective View Table of Contents List of Figures & Tables Abbreviations Main Text Appendices MAIN TEXT PART 1 GENERAL CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... -

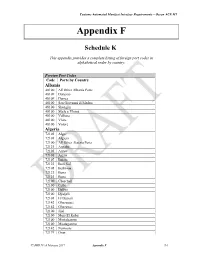

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto. -

Resignations and Appointments

N. 180214b Wednesday 14.02.2018 Resignations and Appointments Resignation of metropolitan archbishop of Jaro, Philippines, and appointment of successor The Holy Father Francis has accepted the resignation from the pastoral care of the metropolitan archdiocese of Jaro, Philippines, presented by H.E. Msgr. Angel N. Lagdameo. The Pope has appointed as metropolitan archbishop of Jaro,Philippines, H.E. Msgr. Jose Romeo Orquejo Lazo, transferring him from the see of San Jose de Antique. H.E. Msgr. Jose Romeo Orquejo Lazo H.E. Msgr. Jose Romeo Orquejo Lazo was born in San Jose de Buenavista Antique, in the diocese of San Jose de Antique, Philippines, on 23 January 1949. He carried out his secondary studies at the Saint Joseph Academy in San Jose, his studies in philosophy at the Saint Peter’s seminary, and finally theology courses at the Saint Vincent Ferrer Major Seminary in Jaro. He then completed further studies at the East Asian Pastoral Institute and the Institute of Pastoral theology in Berkeley, USA. He was ordained a priest for the diocese of San Jose de Antique on 1 April 1975. After some years as a parish priest in Dao, he served as spiritual director between 1978 and 1985, and then rector of the Saint Peter seminary in San Jose de Buenavista. In 1985 he became parish priest of Bugason and, in 1989, vicar general of the diocese of San Jose de Antique and rector of the Cathedral. In 1997 he became a member of the Assist program team organized by the Philippine Episcopate for the ongoing formation of local clergy. -

6. Identification of the Candidate RRTS Routes

THE FEASIBILITY STUDY ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF ROAD RO-RO TERMINAL SYSTEM FOR MOBILITY ENHANCEMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES - FINAL REPORT - 6. Identification of the Candidate RRTS Routes 6.1 Objective of RRTS Development The concept of the nautical highway aims to reduce the transport cost between Mindanao and Luzon and to promote shipping service by establishing an alternative shipping service in addition to traditional shipping service. However, it is generally recognized that, the longer the travel distance, the more advantageous it is to use ships rather than trucks. For long distance shipping, larger ships are being increasingly employed throughout the world to take advantage of the scale of merit. The improvement of the cargo handling productivity is well exhibited at General Santos Port where the long-distance RoRo ferries are the principal carriers of the domestic cargoes. Playing the principal roles domestic cargoes. Figure 6-1 shows the annual variation of the average ship size (GRT), total number of ship calls and cargo volumes loaded and unloaded per ship, while Figure 6-2 shows the average LOA, service time per ship and cargo handling productivity (number of containers handled per hour). Gen. Santos Shipping Statistics 10,000 8,000 GRT Load/Ship 6,000 Shipcalls 4,000 2,000 0 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Source: ITDP, 2006, Vol. III Part III Figure 6-1 Average GRT, Load per ship and annual number of ship calls Gen. Santos Shipping Statistics 160 140 LOA 120 Service Time 100 Productivity 80 60 40 20 0 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Source: ITDP, 2006, Vol. -

The Philippines Are a Chain of More Than 7,000 Tropical Islands with a Fast Growing Economy, an Educated Population and a Strong Attachment to Democracy

1 Philippines Media and telecoms landscape guide August 2012 1 2 Index Page Introduction..................................................................................................... 3 Media overview................................................................................................13 Radio overview................................................................................................22 Radio networks..........……………………..........................................................32 List of radio stations by province................……………………………………42 List of internet radio stations........................................................................138 Television overview........................................................................................141 Television networks………………………………………………………………..149 List of TV stations by region..........................................................................155 Print overview..................................................................................................168 Newspapers………………………………………………………………………….174 News agencies.................................................................................................183 Online media…….............................................................................................188 Traditional and informal channels of communication.................................193 Media resources..............................................................................................195 Telecoms overview.........................................................................................209 -

FBM Page Lists of Sites Opened

LUZON ABUCAY, BATAAN BINGOZONIC BINGO Alyss's Commercial Hub, Brgy. Capitangan, Abucay, Bataan BATANGAS LEMERY BINGO BOUTIQUE Victory Town Center, Atienza St. corner Rizal St., Lemery, Batangas BINGO PARADISE Xentro Mall-Lemery Ilustre Avenue, Brgy. Malinis Lemery, Batangas MYTRON BINGO Alcalanes Bowling Center, Ilustre Ave., Brgy. Palanas, Lemery, Batangas LIPA BINGO TSUNAMI LIPA General Luna Cor., H. Latorre St., Barangay Diez, Lipa City NASUGBU BINGO BOUTIQUE J.P Laurel St. Brgy 9 Nasugbu, Batangas BULACAN BALIUAG BINGO BOUTIQUE PLM Bldg., DRT Highway cor. Benigno Aquino Ave., Bagong Nayon, Baliuag, Bulacan BINGO BOUTIQUE Golf RPC Building, DRT Highway, Brgy. Sta. Barbara, Baliuag, Bulacan BINGO TRONIC St. Agustine Building, Cagayan Valley Road, Poblacion, Baliwag, Bulacan MARKET BINGO G/F SM City Baliuag, DRT Highway, Pagala, Baliuag, Bulacan CALUMPIT BINGO BOUTIQUE Unit 1 KM 46 McArthur Hi-way, Brgy. Pio Cruzcosa Calumpit, Bulacan EBINGO G/F Villa de Calumpit Resort, 279 Pio CruzCosa, Calumpit, BulaCan LANDMARK: LARISIDENCIA GUIGUINTO BINGO BOUTIQUE DG Plaza Guiguinto,#8002 McArthur Highway, Brgy. Ilang-Ilang, Guiguinto, Bulacan /AIFAMART GUIGUIGUINTO MARILAO BINGO BOUTIQUE G/F Hollywood Suites and Resort, McArthur Highway, Ibayo, Marilao, Bulacan BINGO CLUB #311 MCarthur Highway, Abangan Sur, Marilao, BulaCan MARKET BINGO SM City Marilao, Brgy. Ibayo, Marilao, Bulacan LANDMARK SM CITY MEYCAUAYAN BINGO BOUTIQUE LP Plaza Building, MeyCauayan-Camalig Road, Brgy. Iba, MeyCauayan City, BulaCan MUZON E-BINGO MASJ Building Carriedo Street, Brgy. Muzon, San Jose Del Monte City, Bulacan LANDMARK: MERCURY SAN JOSE DEL MONTE BINGO BOUTIQUE V. Casas Bldg. Brgy. Tungkong Mangga, San Jose del Monte City, BulaCan KINGCHAMP BINGO 2/ F SM- San Jose Tungkong Mangga, Quirino Highway, Tungkong Mangga, San Jose Del Monte City, BulaCan LANDMARK SM,SAN JOSE METRO BINGO G/F Starmall San Jose Del Monte BulaCan SAN MIGUEL BINGO BOUTIQE 2/F HBC Building, Norberto St., PoblaCion, San Jose San Miguel, BulaCan LANDMARK HONDA & NOBERTO MARKET" STA.