Significant Learning: Effectively Using Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs in A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reservoir Dogs 1992

04 programação da cinubiteca www.labcom.ubi.pt/cinubiteca universidade da beira interior licenciatura em cinema 23 | março | 04 ciclo { filmes de culto }* reservoir dogs 1992 . EUA . 99’ realização Quentin Tarantino argumento Quentin Tarantino Roger Avary fotografia Andrzej Sekula supervisão musical Karyn Rachtman montagem Sally Menke com Harvey Keitel Tim Roth Michael Madsen Chris Penn Steve Buscemi > Engenho narrativo. Tarantino gosta de contar histórias. Percebemos isso logo neste primeiro filme. E nos filmes seguintes. Ou em qualquer entrevista com o realizador. A arte de narrar não é algo simples, não é uma faculdade democrática. Será um privilégio, > Pop. O filme começa com a exegese de um uma vocação. Tarantino, cinéfilo de hino pop: “Like a Vigin”. Há no filme muito de videoclube, sabe bem que parte da força cultura popular. Tarantino não é um erudito, histórica do cinema lhe vem da sua capacidade não pretende sê-lo. Mas lida com inegável para engendrar ilusões, manipular destreza com imagens, figuras, factos do vasto expectativas, surpreender ou desconcertar (as caldeirão de cores, narrativas, sensações que dedicatórias a Corman ou Godard são, de a cultura urbana do século XX cozinhou. A modo diverso, ilustrativas disso mesmo). vibração é funky, a atitude é cool, alheia à Intrínsecos a toda a boa ficção estão o artifício gravidade do mundo, ao mesmo tempo e o engano: a verdade da mentira. Tarantino próxima da convicção e da presunção. Com a sabe que mais que o conforto, o espectador música dos anos 70 desenha o tom e o ritmo premeia a provocação. “Reservoir Dogs” é um exibição do filme. -

Festival Centerpiece Films

50 Years! Since 1965, the Chicago International Film Festival has brought you thousands of groundbreaking, highly acclaimed and thought-provoking films from around the globe. In 2014, our mission remains the same: to bring Chicago the unique opportunity to see world- class cinema, from new discoveries to international prizewinners, and hear directly from the talented people who’ve brought them to us. This year is no different, with filmmakers from Scandinavia to Mexico and Hollywood to our backyard, joining us for what is Chicago’s most thrilling movie event of the year. And watch out for this year’s festival guests, including Oliver Stone, Isabelle Huppert, Michael Moore, Taylor Hackford, Denys Arcand, Liv Ullmann, Kathleen Turner, Margarethe von Trotta, Krzysztof Zanussi and many others you will be excited to discover. To all of our guests, past, present and future—we thank you for your continued support, excitement, and most importantly, your love for movies! Happy Anniversary to us! Michael Kutza, Founder & Artistic Director When OCTOBEr 9 – 23, 2014 Now in our 50th year, the Chicago International Film Festival is North America’s oldest What competitive international film festival. Where AMC RIVER EaST 21* (322 E. Illinois St.) *unless otherwise noted Easy access via public transportation! CTA Red Line: Grand Ave. station, walk five blocks east to the theater. CTA Buses: #29 (State St. to Navy Pier), #66 (Chicago Red Line to Navy Pier), #65 (Grand Red Line to Navy Pier). For CTA information, visit transitchicago.com or call 1-888-YOUR-CTA. Festival Parking: Discounted parking available at River East Center Self Park (lower level of AMC River East 21, 300 E. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Beer Blood and Ashes by Michael Madsen Mr Blonde's Ambition

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Beer Blood and Ashes by Michael Madsen Mr Blonde's ambition. A fortnight before the American release of Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill Vol 2, its star, Michael Madsen, sits on the upper deck of his Malibu beach home, smoking Chesterfields and watching the dolphins. There are four in the distance, jumping happy arcs through the waves. This morning, though, they're the only ones leaping for joy. 'It's hard, man. I got a big overhead,' says the actor, shaking his head. 'I'm taking care of three different families at the moment. There's my ex- wife, then my mom and my niece. And then there's all this.' He indicates the four-bedroom house behind him where he lives with his third wife and his five sons. It's a great place - bright, white and tall, every wall filled with old movie posters, lovingly framed. He bought it from Ted Danson, who bought it from Walt Disney's daughter, who bought it from the man who built it - Keith Moon of The Who. Since the boys are at school (the eldest is 16) the house is relatively quiet. Besides the whoosh of the Pacific on to his private beach below, all you can hear is his beautiful wife Deanna on the phone in the kitchen, his parrot Marlon squawking merrily downstairs, and Madsen's own quiet, whisky rasp, bemoaning his hard times. 'I'm trying to downscale,' he says. 'I already let two of my motorcycles go and I sold three of my cars - a Corvette, a little Porsche that I had and a '57 Chevy.' He sighs and shrugs. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Reservoir Dogs

RESERVOIR DOGS RESERVOIR DOGS una película de QUENTIN TARANTINO una película de QUENTIN TARANTINO EL DIRECTOR QUENTIN TARANTINO, director, guionista, productor y actor, ha ganado un Oscar y una Palma de Oro. Debutó en 1992 con Reservoir Dogs. Dos años después estrenó una de sus películas más celebradas, Pulp Fiction. Sus siguientes títulos son Asesinos natos, un capítulo de Four Rooms, Jackie Brown, Kill Bill (I y II), Grindhouse: Death Proof, Malditos bastardos, Django desencadenado, Los odiosos ocho., Érase una vez en... Holywood… RESEÑAS DE PRENSA (Crítica publicada en The Guardian el 7 de enero de 1993. Por Dereck Malcolm) Aquí hay un momento en RESERVOIR DOGS en el que es difícil no tomar postura contra la violencia y marcharse. Es cuando Mr. Blonde (Michael Madsen), uno de los ladrones fugitivos que se conocen solo por códigos de colores, tortura a un policía al ritmo de la canción pop Stuck In The Middle With You. Amenaza con echarle gasolina y prenderle fuego. Ya le ha cortado la oreja. Menciono esto porque los críticos, quizás anestesiados por los horrores actuales, a veces no advierten a los posibles espectadores de lo que están a punto de ver en el cine. El thriller de Quentin Tarantino es un primer largometraje violento y sangriento que no le desearía a la tía soltera o al tío susceptible de nadie. Pero también es un debut extraordinariamente impresionante, ya comparado con Mean Streets de Martin Scorsese, pero también con sus posteriores Goodfellas o The Killing de Stanley Kubrick y posi- blemente con el primer gángster de Godard. -

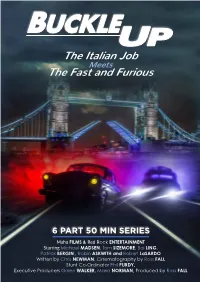

Brochures, Props, Advertising Material and Scripts

BUCKLE UP The Italian Job Meets The Fast and Furious 6 PART 50 MIN SERIES Maha FILMS & Red Rock ENTERTAINMENT Starring Michael MADSEN, Tom SIZEMORE, Bai LING, Patrick BERGIN , Robin ASKWITH and Robert LaSARDO Written by Chris NEWMAN, Cinematography by Ross FALL Stunt Co-Ordinator Phil PURDY, Executive Producers Galen WALKER, Maria NORMAN, Produced by Ross FALL Buckle Up 1 DISCLAIMER: Red Rock Entertainment Ltd is not authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The content of this promotion is not authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA). Reliance on the promotion for the purpose of engaging in any investment activity may expose an individual to a significant risk of losing all of the investment. UK residents wishing to participate in this promotion must fall into the category of sophisticated investor or high net worth individual as outlined by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). BUCKLE UP CONTENTS 4 Concept 5 Synopsis 6 | 7 Series Bible 8 | 15 Cast 16 Director 17 Production 18 | 19 Executive Producers 21 | 22 Perks & Benefits 22 Equity THE CONCEPT The idea came about when brother arranges to buy the Star Like the film The Warriors, Elgar the writer Chris Newman was of Africa on the black market has to make it back from where watching the 1979 film The from an Arab Prince. He sends a he steals the diamond to the Warriors where a New York courier to pick up the diamond younger brother but this time gang had to make it back to necklace. Unknown to him his it’s Cornwall and the destination Coney Island from Manhattan brother has also learned about is London and it’s got to be after a charismatic gang leader the diamond but he doesn’t done in 8 hours. -

Genre, Justice & Quentin Tarantino

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-6-2015 Genre, Justice & Quentin Tarantino Eric Michael Blake University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Scholar Commons Citation Blake, Eric Michael, "Genre, Justice & Quentin Tarantino" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5911 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genre, Justice, & Quentin Tarantino by Eric M. Blake A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies With a concentration in Film Studies College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Andrew Berish, Ph.D. Amy Rust, Ph.D. Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 23, 2015 Keywords: Cinema, Film, Film Studies, Realism, Postmodernism, Crime Film Copyright © 2015, Eric M. Blake TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................1 -

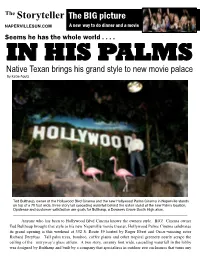

Storyteller the BIG Picture NAPERVILLESUN.COM a New Way to Do Dinner and a Movie Seems He Has the Whole World

The Storyteller The BIG picture NAPERVILLESUN.COM A new way to do dinner and a movie Seems he has the whole world . IN HIS PALMS Native Texan brings his grand style to new movie palace By Katie Foutz Ted Bulthaup, owner of the Hollywood Blvd Cinema and the new Hollywood Palms Cinema in Naperville stands on top of a 70 foot wide, three story tall cascading waterfall behind the usher stand at the new Palms location. Opulence and customer satisfaction are goals for Bulthaup, a Downers Grove South High alum. _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Anyone who has been to Hollywood Blvd Cinema knows the owners style. BIG! Cinema owner Ted Bulthaup brought that style to his new Naperville movie theater, Hollywood Palms Cinema celebrates its grand opening is this weekend at 352 S. Route 59 hosted by Roger Ebert and Oscar-winning actor Richard Dreyfuss. Tall palm trees, bamboo, coffee plants and other tropical greenery nearly scrape the ceiling of the entryway’s glass atrium. A two story, seventy foot wide, cascading waterfall in the lobby was designed by Bulthaup and built by a company that specializes in outdoor zoo enclosures that turns any conversation up to a shouting match over the rush of Hedren, Roger Ebert and more to call or write letters falling water. An art deco pair of gold winged men in support of “The Wizard of Oz” Munchkins re- flanking the screen in one auditorium stand 17 feet ceiving their star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. tall and were movie props in the 20th Century Fox He’s known the famous Little People for years and warehouse. -

The Careers of Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas As Referenced in Literature a Study in Film Perception

The Careers of Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas as Referenced in Literature A Study in Film Perception Henryk Hoffmann Series in Cinema and Culture Copyright © 2020 Henryk Hoffmann. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Cinema and Culture Library of Congress Control Number: 2020942585 ISBN: 978-1-64889-036-9 Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by Freepik and PublicDomainPictures from Pixabay. Selections from Getting Garbo: A Novel of Hollywood Noir , copyright 2004 by Jerry Ludwig, used by permission of Sourcebooks. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. To the youngest members of the family— Zuzanna Maria, Ella Louise, Tymon Oskar and Graham Joseph— with utmost admiration, unconditional love, great expectations and best wishes Table of contents List of Figures vii Introduction ix PART ONE. -

Reservoir Dogs Tarentino En Technicolor Reservoir Dogs, États-Unis 1992, 99 Min

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 23:28 Séquences La revue de cinéma Reservoir Dogs Tarentino en technicolor Reservoir Dogs, États-Unis 1992, 99 min. Olivier Bourque Numéro 261, juillet–août 2009 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1906ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (imprimé) 1923-5100 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Bourque, O. (2009). Compte rendu de [Reservoir Dogs : Tarentino en technicolor / Reservoir Dogs, États-Unis 1992, 99 min.] Séquences, (261), 32–32. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2009 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ ARRÊT SUR IMAGE I FLASH-BACK Reservoir Dogs Tarentino en technicolor Premier film de Quentin Tarantino, Reservoir Dogs n'a pas eu le succès escompté à sa sortie après avoir cartonné lors de la Quinzaine des réalisateurs à Cannes en 1992. Mais le temps fait bien les choses. Après le succès de Pulp Fiction, les spectateurs ont découvert la « coolitude » et l'originalité du premier essai du réalisateur américain au point d'en faire une œuvre culte. -

DP Bording Gate 11/05/07 16:19 Page 2

DP BordingGate11/05/0716:19Page24 Design: Benjamin Seznec • TROÎKA DP Bording Gate 11/05/07 16:19 Page 2 François Margolin presents A thriller by Olivier Assayas MIDNIGHT SCREENING International Press World Sales RICHARD LORMAND MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL France, 2007, 106', World Cinema Publicity 6, Cité Paradis colour, Scope, SRD www.filmpressplus.com Tel: +33 1 53 34 90 20 [email protected] Fax: +33 1 42 47 11 24 In Cannes (May 15-27): 75010 PARIS In Cannes Tel: 06 1585 9198 [email protected] 5, La Croisette (1st Floor) 06 2424 1654 www.memento-films.com 06 06 98 76 32 06 2416 3731 DP Bording Gate 11/05/07 16:19 Page 4 Synopsis Sexy ex-prostitute Sandra (Asia Argento) hooks up again with debt-ridden entrepreneur Miles (Michael Madsen). Mixed signals incite the former lovers to give it another go, but rekindling an old romance isn't on Sandra's agenda. She is forced to flee to Hong Kong to seek out a new life. Attractive young couple Lester (Carl Ng) and Sue (Kelly Lin) promise Sandra papers and money. Nothing turns out as expected for Sandra, whose feelings and intentions remain a mystery till the end. DP Bording Gate 11/05/07 16:19 Page 6 CommentsOlivier from Assayas ORIGIN OF THE PROJECT In March 2006, I scouted locations for BOARDING GATE, followed by Paris A news brief caught my eye about the murder of French financier Edouard pre-production to start shooting in July 2006. We shot for six weeks, three Stern during an S&M session. -

Kill Bill Volumes 1 and 2

Kill Bill Volumes 1 and 2 directed by Quentin Tarantino Miramax Film Corporation, 2004 The Emperor’s new clothes: volumes 1 & 2 by driving a table leg through his heart. blame Robert Redford. It’s all his fault After the two-for-one failure of Jackie Brown really. When he bailed out a small, Utah- and his acting career, Tarrantino disappeared Ibased independent film festival, the and spent a couple of years sulking, licking Sundance Film Festival was born. Under his his wounds and battling writer’s block. But guardianship, Sundance has become one of now he’s back, louder than ever, with his the most influential film festivals in the magnum opus, Kill Bill Volumes 1 & 2, world, championing the best modern based, apparently, on several drunken American and international independent film conversations between Tarrantino and Uma makers, among them the Coen Brothers and Thurman while they were filming Pulp Steven Soderbergh. And Quentin Tarantino. Fiction. Kill Bill is a sprawling martial arts epic charting the globetrotting vengeance A model of low-budget independent cinema, wrought by The Bride (Uma Thurman), a 1992’s Reservoir Dogs was fresh, vibrant, pregnant assassin, who is shot and left for funny and violent; a showcase for Tarantino’s dead on her wedding day on the orders of her pop culture sensibilities, his perverse sense of former lover and employer, Bill. Waking up humour and his cheerfully vulgar dialogue, from a coma 5 years later, The Bride is which amused and offended audiences in understandably a little bit peeved and sets out equal measure.