Testing the TOEIC: Practicality, Reliability and Validity in the Test of English for International Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Requirements for CEMS MIM Page 1 of 7

Appendix No. 1. Language requirements for CEMS MIM Page 1 of 7 APPENDIX No. 1 to the CEMS MIM Selection Rules & Regulations LANGUAGE REQUIREMENTS FOR CEMS MIM (last update 2 October 2019) 1. According to the CEMS MIM requirements, all candidates must present one of the following certificates of their proficiency in English, which automatically is their first foreign language (FL 1): a) TOEFL (PBT/CBT/iBT) with the result of 600/250/100 or higher, b) IELTS at 7.0 level or higher, c) CAE at „B” level or higher d) CPE (Grade A, B, C, or C1 Certificate) e) BEC Higher (Grade “A” only) f) GCSE (A-Level) exam issued in Singapore 2. Exemption from the above rule is granted to: a) graduates of undergraduate or graduate level study programmes (with English as the language of instruction) at CEMS member universities/schools, or universities/schools that are EQUIS or AACSB International accredited, or issued in an English-speaking country; b) students who successfully completed CEMS Accredited Course in English at C1 or C2 level (both written and oral). 3. Proof of proficiency in the second foreign language (FL2) is optional and verified on the basis of: a) SGH Language Competence Tests (since September 2017 conducted in a form of control test organised during the 1st semester of MA studies) passed with minimum score 60 points (taken in the calendar year calculated according to the following formula: x-2, where “x” stands for the calendar year in which the selection takes place), b) CNJO certificate on completing SGH tutorials in foreign language for economics (zaświadczenie o ukończeniu lektoratu z języka obcego ekonomicznego) at minimum level of B1, c) commercial tests’ certificates listed in the Table 1 passed at B2 or B1 minimum level, provided they fulfil validity periods, as stipulated in clause 4. -

A List of Certificates Confirming the Knowledge of a Modern Foreign Language at the Level of at Least B2, Recognized by the Doctoral School in the Recruitment Process

Appendix no 4 to the Admission Rules to the Doctoral School of the Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music in Gdańsk in the academic year 2020/2021 A list of certificates confirming the knowledge of a modern foreign language at the level of at least B2, recognized by the Doctoral School in the recruitment process. Persons who do not have any of the certificates listed below before matriculation will have to pass an exam in a modern foreign language at B2 level, organized by the Foreign Languages Unit of the Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music in Gdańsk. This exam will be held in September 20..... Certificates confirming at least B2 level of global language proficiency according to the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)": 1. Certificate confirming the knowledge of a foreign language, issued by the National School of Public Administration as a result of a linguistic verification procedure. 2. Certificates confirming at least B2 level of global language proficiency according to the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)": 1) certificates issued by institutions associated in the Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) - ALTE Level 3 (B2), ALTE Level 4 (C1), ALTE Level 5 (C2), in particular the certificates: a) First Certificate in English (FCE), Certificate in Advanced English (CAE), Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE), Business English Certificate (BEC) Vantage — at least Pass, Business English Certificate (BEC) -

Language Requirements

Language Policy NB: This Language Policy applies to applicants of the 20J and 20D MBA Classes. For all other MBA Classes, please use this document as a reference only and be sure to contact the MBA Admissions Office for confirmation. Last revised in October 2018. Please note that this Language Policy document is subject to change regularly and without prior notice. 1 Contents Page 3 INSEAD Language Proficiency Measurement Scale Page 4 Summary of INSEAD Language Requirements Page 5 English Proficiency Certification Page 6 Entry Language Requirement Page 7 Exit Language Requirement Page 8 FL&C contact details Page 9 FL&C Language courses available Page 12 FL&C Language tests available Page 13 Language Tuition Prior to starting the MBA Programme Page 15 List of Official Language Tests recognised by INSEAD Page 22 Frequently Asked Questions 2 INSEAD Language Proficiency Measurement Scale INSEAD uses a four-level scale which measures language competency. This is in line with the Common European Framework of Reference for language levels (CEFR). Below is a table which indicates the proficiency needed to fulfil INSEAD language requirement. To be admitted to the MBA Programme, a candidate must be fluent level in English and have at least a practical level of knowledge of a second language. These two languages are referred to as your “Entry languages”. A candidate must also have at least a basic level of understanding of a third language. This will be referred to as “Exit language”. LEVEL DESCRIPTION INSEAD REQUIREMENTS Ability to communicate spontaneously, very fluently and precisely in more complex situations. -

English Language Testing in US Colleges and Universities

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 331 284 FL 019 122 AUTHOR Douglas, Dan, Ed. TITLE English Language Testing in U.S. Colleges and Universities. INSTITUTION National Association for Foreign Student Affairs, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY United States information Agency, Washington, DC. Advisory, Teaching, and Specialized Programs Div. REPORT NO /SBN-0-912207-56-6 PUB DATE 90 NOTE 106p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Admission Criteria; College Admission; *English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Foreign Students; Higher Education; *Language Tests; Questionnaires; Second Language Programs; Standardized Tests; Surveys; *Teaching Assistants; *Test Interpretation; Test Results; Writing (Composition); Writing Tests IDENTIFIERS United Kingdom ABSTRACT A collection of essays and research reports addresses issues in the testing of English as a Second Language (ESL) among foreign students in United States colleges and universities. They include the following: "Overview of ESL Testing" (Ralph Pat Barrett); "English Language Testing: The View from the Admissions Office" (G. James Haas); "English Language Testing: The View from the English Teaching Program" (Paul J. Angelis); "Standardized ESL Tests Used in U.S. Colleges and Universities" (Harold S. Madsen); "British Tests of English as a Foreign Language" (J. Charles Alderson); "ESL Composition Testing" (Jane Hughey); "The Testing and Evaluation of International Teaching Assistants" (Barbara S. Plakans, Roberta G. Abraham); and "Interpreting Test Scores" (Grant Henning). Appended materials include addresses for use in obtaining information about English language testing, and the questionnaire used in a survey of higher education institutions, reported in one of the articles. (ME) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Fremdsprachenzertifikate in Der Schule

FREMDSPRACHENZERTIFIKATE IN DER SCHULE Handreichung März 2014 Referat 522 Fremdsprachen, Bilingualer Unterricht und Internationale Abschlüsse Redaktion: Henny Rönneper 2 Vorwort Fremdsprachenzertifikate in den Schulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen Sprachen öffnen Türen, diese Botschaft des Europäischen Jahres der Sprachen gilt ganz besonders für junge Menschen. Das Zusammenwachsen Europas und die In- ternationalisierung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft verlangen die Fähigkeit, sich in mehreren Sprachen auszukennen. Fremdsprachenkenntnisse und interkulturelle Er- fahrungen werden in der Ausbildung und im Studium zunehmend vorausgesetzt. Sie bieten die Gewähr dafür, dass Jugendliche die Chancen nutzen können, die ihnen das vereinte Europa für Mobilität, Begegnungen, Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung bietet. Um die fremdsprachliche Bildung in den allgemein- und berufsbildenden Schulen in Nordrhein-Westfalen weiter zu stärken, finden in Nordrhein-Westfalen internationale Zertifikatsprüfungen in vielen Sprachen statt, an denen jährlich mehrere tausend Schülerinnen und Schüler teilnehmen. Sie erwerben internationale Fremdsprachen- zertifikate als Ergänzung zu schulischen Abschlusszeugnissen und zum Europäi- schen Portfolio der Sprachen und erreichen damit eine wichtige Zusatzqualifikation für Berufsausbildungen und Studium im In- und Ausland. Die vorliegende Informationsschrift soll Lernende und Lehrende zu fremdsprachli- chen Zertifikatsprüfungen ermutigen und ihnen angesichts der wachsenden Zahl an- gebotener Zertifikate eine Orientierungshilfe geben. -

Types of Documents Confirming the Knowledge of a Foreign Language by Foreigners

TYPES OF DOCUMENTS CONFIRMING THE KNOWLEDGE OF A FOREIGN LANGUAGE BY FOREIGNERS 1. Diplomas of completion of: 1) studies in the field of foreign languages or applied linguistics; 2) a foreign language teacher training college 3) the National School of Public Administration (KSAP). 2. A document issued abroad confirming a degree or a scientific title – certifies the knowledge of the language of instruction 3. A document confirming the completion of higher or postgraduate studies conducted abroad or in Poland - certifies the knowledge of the language only if the language of instruction was exclusively a foreign language. 4. A document issued abroad that is considered equivalent to the secondary school-leaving examination certificate - certifies the knowledge of the language of instruction 5. International Baccalaureate Diploma. 6. European Baccalaureate Diploma. 7. A certificate of passing a language exam organized by the following Ministries: 1) the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; 2) the ministry serving the minister competent for economic affairs, the Ministry of Cooperation with Foreign Countries, the Ministry of Foreign Trade and the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Marine Economy; 3) the Ministry of National Defense - level 3333, level 4444 according to the STANAG 6001. 8. A certificate confirming the knowledge of a foreign language, issued by the KSAP as a result of linguistic verification proceedings. 9. A certificate issued by the KSAP confirming qualifications to work on high-rank state administration positions. 10. A document confirming -

An Overview of the Issues on Incorporating the TOEIC Test Into the University English Curricula in Japan TOEIC テストを大学英語カリキュラムに取り込む問題点について

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE 127 An Overview of the Issues on Incorporating the TOEIC test into the University English Curricula in Japan TOEIC テストを大学英語カリキュラムに取り込む問題点について Junko Takahashi Abstract: The TOEIC test, which was initially developed for measuring general English ability of corporate workers, has come into wide use in educational institutions in Japan including universities, high schools and junior high schools. The present paper overviews how this external test was incorporated into the university English curriculum, and then examines the impact and influence that the test has on the teaching and learning of English in university. Among various uses of the test, two cases of the utilization will be discussed; one case where the test score is used for placement of newly enrolled students, and the other case where the test score is used as requirements for a part or the whole of the English curriculum. The discussion focuses on the content and vocabulary of the test, motivation, and the effectiveness of test preparation, and points out certain difficulties and problems associated with the incorporation of the external test into the university English education. Keywords: TOEIC, university English curriculum, proficiency test, placement test 要約:企業が海外の職場で働く社員の一般的英語力を測定するために開発された TOEIC テストが、大学や中学、高校の学校教育でも採用されるようになった。本稿は、 TOEIC という外部標準テストが大学内に取り込まれるに至る経緯を概観し、テストが 大学の英語教育全般に及ぼす影響および問題点を考察する。大学での TOEIC テストの 利用法は多岐に及ぶが、その中で特にクラス分けテストとしての利用と単位認定や成 績評価にこのテストのスコアを利用する 2 種類の場合を取り上げ、テストの内容・語 彙、動機づけ、受験対策の効果などの観点から、外部標準テストの利用に伴う困難点 を論じる。 キーワード:TOEIC、大学英語教育カリキュラム、実力テスト、クラス分けテスト 1. Background of the TOEIC Test 1. 1 Socio-economic pressure on English education The TOEIC (Test of English for International Communication) test is an English proficiency test for the speakers of English as a second or foreign language developed by the Educational Testing Service (ETS), the same organization which creates the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) test. -

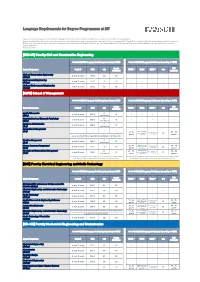

Language Requirements for Degree Programmes at DIT

Language Requirements for Degree Programmes at DIT Applicants must provide proof of the relevant language skills for the respective degree programme in order to be admitted to the programme. Unless provided otherwise by the study and examination regulations of the respective programme, the proof of German language skills at level B1 (or higher) for Bachelor programmes conducted purely in English and at level A2 (or higher) for Master programmes conducted purely in English (levels as per the Common European Framework of Reference) should additionally be provided by the end of the degree programme. Exceptions: see * [BIW-UT] Faculty Civil and Construction Engineering Proof of GERMAN Language Proficiency (according to CEFR) Proof of ENGLISH Language Proficiency (according to CEFR) Goethe PTE Degree Programme TestDaF DSH telc TOEFL * TOEIC IELTS * telc Certificate Academic Civil and Construction Engineering at least 12 pointsDSH 2B2B2----- (B.Eng.) Environmental Engineering at least 12 pointsDSH 2B2B2----- (B.Eng.) Civil and Environmental Engineering at least 12 pointsDSH 2B2B2----- (M.Eng.) [AWW] School of Management Proof of GERMAN Language Proficiency (according to CEFR) Proof of ENGLISH Language Proficiency (according to CEFR) Goethe PTE Degree Programme TestDaF DSH telc TOEFL * TOEIC IELTS * telc Certificate Academic Applied Economics C1 at least 15 points DSH 2 C1----- (B.Sc.) Hochschule Organisational and Economic Psychology C1 at least 15 points DSH 2 C1----- (B.Sc.) Hochschule Business Administration C1 at least 15 points DSH 2 C1----- (B.A.) Hochschule International Management ---- (B.A.) listening 400-485 72 - 94 5.5 - 6.5 points in 59 - 75 points, reading 385- each section B2 points 450 points * As part of "Foreign Language I to III" one language must be completed at least with level A1. -

Mapping English Language Proficiency Test Scores

Mapping English Language Proficiency Test Scores Onto the Common European Framework Mapping English Language Proficiency Test Scores Onto the Common European Framework Richard J. Tannenbaum and E. Caroline Wylie ETS, Princeton, NJ RR-05-18 ETS is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer. As part of its educational and social mission and in fulfilling the organization's non-profit Charter and Bylaws, ETS has and continues to learn from and also to lead research that furthers educational and measurement research to advance quality and equity in education and assessment for all users of the organization's products and services. Copyright © 2005 by ETS. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Violators will be prosecuted in accordance with both U.S. and international copyright laws. EDUCATIONAL TESTING SERVICE, ETS, the ETS logos, Graduate Record Examinations, GRE, TOEFL, the TOEFL logo, TOEIC, TSE, and TWE are registered trademarks of Educational Testing Service. Test of English as a Foreign Language, Test of Spoken English, Test of Written English, and Test of English for International Communication are trademarks of Educational Testing Service. College Board is a registered trademark of the College Entrance Examination Board. Graduate Management Admission Test and GMAT are registered trademarks of the Graduate Management Admission Council. Abstract The Common European Framework describes language proficiency in reading, writing, speaking, and listening on a six-level scale. The Framework provides a common language with which to discuss students’ progress. -

English-As-A-Second-Language Programs for Matriculated Students in the United States: an Exploratory Survey and Some Issues

Research Report ETS RR–14-11 English-as-a-Second-Language Programs for Matriculated Students in the United States: An Exploratory Survey and Some Issues Guangming Ling Mikyung Kim Wolf Yeonsuk Cho Yuan Wang December 2014 ETS Research Report Series EIGNOR EXECUTIVE EDITOR James Carlson Principal Psychometrician ASSOCIATE EDITORS Beata Beigman Klebanov Donald Powers Research Scientist ManagingPrincipalResearchScientist Heather Buzick Gautam Puhan Research Scientist Senior Psychometrician Brent Bridgeman John Sabatini Distinguished Presidential Appointee ManagingPrincipalResearchScientist Keelan Evanini Matthias von Davier Managing Research Scientist Senior Research Director Marna Golub-Smith Rebecca Zwick Principal Psychometrician Distinguished Presidential Appointee Shelby Haberman Distinguished Presidential Appointee PRODUCTION EDITORS Kim Fryer Ayleen Stellhorn Manager, Editing Services Editor Since its 1947 founding, ETS has conducted and disseminated scientific research to support its products and services, and to advance the measurement and education fields. In keeping with these goals, ETS is committed to making its research freely available to the professional community and to the general public. Published accounts of ETS research, including papers in the ETS Research Report series, undergo a formal peer-review process by ETS staff to ensure that they meet established scientific and professional standards. All such ETS-conducted peer reviews are in addition to any reviews that outside organizations may provide as part of their own publication processes. Peer review notwithstanding, the positions expressed in the ETS Research Report series and other published accounts of ETS research are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Officers and Trustees of Educational Testing Service. The Daniel Eignor Editorship is named in honor of Dr. -

List of Certificates Documenting Language Fluency Level to the Recruitment Process for the Erasmus Program at SUM for OUTGOING STUDENTS (Academic Year 2019/2020)

List of certificates documenting language fluency level to the recruitment process for the Erasmus program at SUM for OUTGOING STUDENTS (academic year 2019/2020) List of certificates documenting English language fluency level 1. First Certificate in English (FCE), 2. Certificate in Advanced English (CAE), 3. Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE), 4. Business English Certificate (BEC) Vantage – at least Pass, 5. Business English Certificate (BEC) Higher, 6. Certificate in English for International Business and Trade (CEIBT) – certificates issued by the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate and the University of Cambridge ESOL Examinations, 7. International English Language Testing System IELTS – above 6 points – certificates issued by the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate, the British Council and Education Australia, 8. Certificate in English Language Skills (CELS) – levels “Vantage” (B2) and “Higher” (C1), 9. Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) – at least 510 points obtained on the test (in electronic system at least 180 points) and at least 3,5 points in written part TWE – issued by Educational Testing Service, Princeton, USA, 10. English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) - First Class Pass at Intermediate Level, Higher Intermediate Level, Advanced Level – issued by City & Guilds Pitman Qualifications (Pitman Qualifications Institute), 11. International English for Speakers of Other Languages (IESOL) – “Communicator” level, “Expert” level, “Mastery” level – issued by City & Guilds (City & Guilds Pitman Qualifications), 12. City & Guilds Level 1 Certificate in ESOL International (reading, writing and listening) Communicator (B2) 500/1765/2; City & Guilds Level 2 Certificate in ESOL International (reading, writing and listening), Expert (C1) 500/1766/4; City & Guilds Level 3 Certificate in ESOL International (reading, writing and listening) Mastery (C2) 500/1767/6 – issued by City & Guilds, 13. -

Correspondència Entre Els Nivells Comuns De Referència Per A

Correspondència entre els nivells comuns de referència per a les llengües del Consell d’Europa i els Certificats d’idiomes reconeguts a efectes de la convocatòria d’ajuts a la mobilitat internacional de l’estudiantat amb reconeixement acadèmic de les universitats de Catalunya per al curs 2016- 2017 (MOBINT). Correspondència entre els nivells comuns de referència per a les llengües del Consell d’Europa i els Certificats d’idiomes reconeguts a efectes de la convocatòria MOBINT El Marc de referència europeu per a l’aprenentatge, l’ensenyament i l’avaluació de llengües és un document elaborat pel Consell d’Europa que té per objectiu proporcionar unes bases comunes per a la descripció d’objectius, continguts i mètodes per a l’aprenentatge de llengües de manera que els cursos, els programes i les qualificacions descriguin d’una manera exhaustiva el que han d’aprendre a fer els aprenents de llengua a l’hora de comunicar-se i quins coneixements i habilitats han de desenvolupar per ser capaços d’actuar de manera efectiva. Aquest marc de referència s’estructura en 6 nivells: Descripció dels Nivells comuns de referència per a les llengües del consell d'Europa Usuari bàsic A1 L’aprenent / usuari pot comprendre i utilitzar expressions quotidianes i familiars i frases molt senzilles encaminades a satisfer les primeres necessitats. Pot presentar-se i presentar una tercera persona i pot formular i respondre preguntes sobre detalls personals com ara on viu, la gent que coneix i les coses que té. Pot interactuar d’una manera senzilla a condició que l’altra persona parli a poc a poc i amb claredat i que estigui disposada a ajudar.