Petitioner, V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2002 Opinions

ERIE COUNTY LEGAL JOURNAL (Published by the Committee on Publications of the Erie County Legal Journal and the Erie County Bar Association) Reports of Cases Decided in the Several Courts of Erie County for the Year 2002 LXXXV ERIE, PA JUDGES of the Courts of Erie County during the period covered by this volume of reports COURTS OF COMMON PLEAS HONORABLE WILLIAM R. CUNNINGHAM -------- President Judge HONORABLE GEORGE LEVIN ---------------------------- Senior Judge HONORABLE ROGER M. FISCHER ----------------------- Senior Judge HONORABLE FRED P. ANTHONY --------------------------------- Judge HONORABLE SHAD A. CONNELLY ------------------------------- Judge HONORABLE JOHN A. BOZZA ------------------------------------ Judge HONORABLE STEPHANIE DOMITROVICH --------------------- Judge HONORABLE ERNEST J. DISANTIS, JR. ------------------------- Judge HONORABLE MICHAEL E. DUNLAVEY -------------------------- Judge HONORABLE ELIZABETH K. KELLY ----------------------------- Judge HONORABLE JOHN J. TRUCILLA --------------------------------- Judge Volume 85 TABLE OF CASES -A- Ager, et al. v. Steris Corporation ------------------------------------------------ 54 Alessi, et al. v. Millcreek Township Zoning Hearing Bd. and Sheetz, et al. 77 Altadonna; Commonwealth v. --------------------------------------------------- 90 American Manufacturers Mutual Insurance Co.; Odom v. ----------------- 232 Azzarello; Washam v. ------------------------------------------------------------ 181 -B- Beaton, et. al.; Brown v. ------------------------------------------------------------ -

United States of America First Circuit Court of Appeals

United States of America First Circuit Court of Appeals NO. 08-2300 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. CIRINO GONZALEZ, Defendant/Appellant BRIEF OF DEFENDANT - APPELLANT By: Joshua L. Gordon, Esq. N.H. Bar No. 9046, Mass. Bar No. 566630 Law Office of Joshua L. Gordon 26 S. Main St., #175 Concord, NH 03301 (603) 226-4225 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......................................... iii STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION....................................1 STATEMENT OF ISSUES...........................................2 STATEMENT OF FACTS AND STATEMENT OF THE CASE.............4 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........................................6 ARGUMENT......................................................8 Convictions I. Mr. Gonzalez Was Convicted of Accessory and Conspiracy to Accessory, but not Conspiracy to Impede Officers..............8 A. Indictment.........................................8 B. Jury Instructions...................................11 C. Special Verdict....................................12 D. Sentencing for Dual-Object Conspiracy.................14 II. Mr. Gonzalez is Not Guilty of Count II Conspiracy............15 A. Government Did Not Prove All Elements of Conspiracy...15 B. Precedents Involving Conjunctive Indictments and Disjunctive Instructions Do Not Apply to Mr. Gonzalez’s Case...................................18 III. Count III Accessory after the Fact Indictment Failed to State an Element...............................................21 IV. No Evidence to Prove Mr. Gonzalez Knew the Elements of the Browns’ -

Historical and Clinical Study of Criminality with Special Reference to Theft, an Fred Brown

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 21 Article 7 Issue 3 November Fall 1930 Historical and Clinical Study of Criminality with Special Reference to Theft, An Fred Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Fred Brown, Historical and Clinical Study of Criminality with Special Reference to Theft, An, 21 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 400 (1930-1931) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. AN HISTORICAL AND CLINICAL STUDY OF CRIMINALITY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THEFT1 FRED BROWN TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. Introduction Chapter II. Theft and the Offender in Primitive Society. Chapter III. Crime and the Offender in Ancient Times Chapter IV. Theories of Crime in the Middle Ages Chapter V. Attitudes and Theories from the Beginning of the Eighteenth to the End of the Nineteenth Cen- tury Chapter VI. Contemporary Theories and -Studies of Crim- inality Bibliography AN HISTORICAL AND CLINICAL STUDY OF CRIMINALITY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THEFT "Enemy" shall ye say but not "Villain," "Invalid" shall ye say but not "Wretch," "Fool" shall ye say but not "Sinner." "Hearken, ye judges! There is another madness besides, and it is before the deed. Ah! ye have not gone deep enough into this soul." -Thus Spake Zarathustra. -

Town of St. Joseph

TOWN OF ST. JOSEPH INVESTIGATIVE AUDIT ISSUED MARCH 1, 2016 LOUISIANA LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR 1600 NORTH THIRD STREET POST OFFICE BOX 94397 BATON ROUGE, LOUISIANA 70804-9397 LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR DARYL G. PURPERA, CPA, CFE DIRECTOR OF INVESTIGATIVE AUDIT ROGER W. HARRIS, J.D., CCEP Under the provisions of state law, this report is a public document. A copy of this report has been submitted to the Governor, to the Attorney General, and to other public officials as required by state law. A copy of this report is available for public inspection at the Baton Rouge office of the Louisiana Legislative Auditor and at the office of the parish clerk of court. This document is produced by the Louisiana Legislative Auditor, State of Louisiana, Post Office Box 94397, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70804-9397 in accordance with Louisiana Revised Statute 24:513. Eight copies of this public document were produced at an approximate cost of $31.20. This material was produced in accordance with the standards for state agencies established pursuant to R.S. 43:31. This report is available on the Legislative Auditor’s website at www.lla.la.gov. When contacting the office, you may refer to Agency ID No. 2321 or Report ID No. 50140032 for additional information. In compliance with the Americans With Disabilities Act, if you need special assistance relative to this document, or any documents of the Legislative Auditor, please contact Elizabeth Coxe, Chief Administrative Officer, at 225-339-3800. LOUISIANA LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR DARYL G. PURPERA, CPA, CFE March 1, 2016 THE HONORABLE EDWARD BROWN, MAYOR, AND MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF ALDERMEN TOWN OF ST. -

United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit

Case: 10-1081 Document: 00116320473 Page: 1 Date Filed: 01/19/2012 Entry ID: 5611724 United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit No. 09-2402 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. ELAINE BROWN, Defendant, Appellant, No. 10-1081 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. EDWARD BROWN, Defendant, Appellant. APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE [Hon. George Z. Singal, U.S. District Judge] Before Lynch, Chief Judge, Lipez and Thompson, Circuit Judges. Case: 10-1081 Document: 00116320473 Page: 2 Date Filed: 01/19/2012 Entry ID: 5611724 Leslie Feldman-Rumpler for appellant Elaine Brown. Dean Stowers, with whom Stowers Law Firm was on brief, for appellant Edward Brown. Seth R. Aframe, Assistant United States Attorney, with whom John P. Kacavas, United States Attorney was on brief, for appellee. January 19, 2012 Case: 10-1081 Document: 00116320473 Page: 3 Date Filed: 01/19/2012 Entry ID: 5611724 THOMPSON, Circuit Judge. A nine-month long stand-off between United States Marshals (the "Marshals") and husband and wife team, Edward and Elaine Brown, resulted in the Browns' criminal convictions. Edward and Elaine1 each appealed and we consolidated. Both claim that the district court committed a myriad of errors justifying reversal. After careful consideration, we reject each argument and affirm. BACKGROUND2 A. The Tax Evasion Trial To put this appeal in context, we begin with another criminal matter involving the Browns. In April 2006, Edward and Elaine were indicted by a federal grand jury on charges relating to their failure to pay federal income tax - an omission that stemmed from the Browns' belief that they were not legally obligated to do so. -

Jackson, Me: “Swedish Panel ” and “Queen $47, Are Being Rapidly Picked Up

The Clinton Independent. ST. JOHNS, MICH., THURSDAY MORNING, MAY 5, 1892. VOL. XXVI.—NO. 32! WHOLE NO-1333 THE PROMISE OF SPRING. !OUR SPRING OPENING SALE —The new Sunday morning train from —The Racine (Wis.) Daily Times says MARRIED. Special Good Bargains in Millinery. CONTINUES THIS WEEK. the west now ’ brings the Sunday morn that Madame Fry’s Concert Co. is the O, day of God, thou brlngest back HEMMINGWAY—PENNINGTON—At8t John ’s A cyclone in prices brought crowds of ing Grand Rapids Democrat to our best of the best. The Bluffing of the birds, rectory by Rev. R. D. Stearns, April 30, appreciative patrons to our Special EXCEPTIONAL BARGAINS ON village. —Walter Davies, of Riley, recently With music for the hearts that lack, 18W, Goo. JF. Hcmralngway, of Westphalia, Trimmed Hat Sale last week. More musical than words! to Miss Katha T. Pennington, of Eagle. SATURDAY ! —Fildew & Millman, druggists, have purchased of It. G. Steel, of this village, On Friday and Satuiday of this week Thou meltest now the frozen deep we place on sale, at the same price. just added a new and handsome revolv a Victor bicycle, model C. Where dreaming love lay bound; BUSINESS LOCALS Trimmed Hats of equal, if not better ggr*To all new subscribers, ut well u to ing perfumery case and a novel cigar Thou wakest life in buds asleep. value. The best goods for the money —Reserved seat sale for Madam Fry’s And Joy in skies that frowned. This Means You. those who will pay up all arrearages, we case to their store furniture. -

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES 156 Ptfth AVENUE * NEW YORK 163, N

an OCEANA PUBLICATION . AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES 156 PtFTH AVENUE * NEW YORK 163, N. Y. 42nd ANNUAL REPORT July 1, 1961 To June 30, 1962 FREEDOM THROUGH DISSENT AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION 156 Fifth Avenue New York 10, N. Y. Published for the American Civil Liberties Union by Oceana Publications, Inc. Board of Directors ChuirmullcEmest Angell Vice Chui rmen-Ralph S. Brown, Jr., Mrs. Sophia Yamall Jacobs General CounseGEdward J. Em& Osmond K. Fraenkel Secretary-Dorothy Kenyon TTewTer-B. W. Huebsch Directors Emeritus-Morris L. Ernst, John F. Finerty, John Holmes, Norman Thomas Robert Bierstedt John Paul Jones ~g~ti~gshker Robert L. Crowell Dan Lacy Walter Frank Will Maslow George Soll Lewis Galantiere Harry C. Meserve Stephen C. Vladeck Walter Gellhom Edward 0. Miller gy=g=inr: Louis M. Hacker Walter Millis August Heckscher Gerard Pie1 Howard Whiteside Frank S. Home Mrs. Harriet Pilpel Edward Bennett Williams National Committee ChuirmalcFrancis Biddle Vice-Chairmen--Pearl S. Buck, Howard F. Bums, Albert Sprague Coolidge, J. Frank Dobie, Lloyd K. Garrison, Frank P. Graham, Palmer Hoyt, Karl Memringer, Loren Miller, Morris Rubin, Lillian E. Smith Mrs. Sadie Alexander Prof. Thomas H. Eliot Dr. Millicent C. McIntosh 1. Garner Anthony Victor Fischer Dr. Alexander Meiklejohn Thurman Arnold Walter T. Fisher Sylvan Meyer Clarence E. A es James Lawrence Fly Donald R. Murphy ~BLl$d cr.wm Dr. Erich Fromm Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer Prof. Ral h F. Fuchs John B. Orr, Jr. Dr. Sarah Gibson Blanding Prof. W it ard E. Godin Bishon G. Bromlev Oxnam Catherine Drinker Bowen Prof. Mark Dew. Howe Jamei G. -

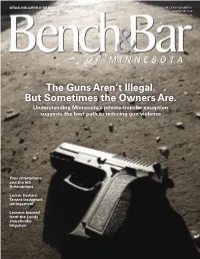

The Guns Aren't Illegal. but Sometimes the Owners Are

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE MINNESOTA STATE BAR ASSOCIATION VOLUME LXXVI NUMBER V MAY/JUNE 2019 www.mnbar.org The Guns Aren’t Illegal. But Sometimes the Owners Are. Understanding Minnesota’s private-transfer exception suggests the best path to reducing gun violence Your smartphone and the 5th Amendment Lessor beware: Tenant trademark infringement Lessons learned from the Lunds shareholder litigation Only 2019 MSBA CONVENTION $125 June 27 & 28, 2019 • Mystic Lake Center • www.msbaconvention.org for MSBA Members EXPERIENCE THE BEST 12:15 – 12:30 p.m. 4:00 – 5:00 p.m. 9:40 – 10:40 a.m. THURSDAY, JUNE 27 Remarks by American Bar Association President ED TALKS BREAKOUT SESSION D OF THE BAR Bob Carlson 7:30 – 8:30 a.m. • Making the Case for Sleep 401) Someone Like Me Can Do This – CHECK-IN & CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST 12:30 – 12:45 p.m. Dr. John Parker; Sleep Performance Institute; Minneapolis Stories of Latino Lawyers and Judges What do lawyers, judges, academics, activists, technologists and business leaders in Minnesota Passing of the Gavel Ceremony have in common? They will all be at the 2019 MSBA Convention engaging in a rich, 7:45 – 8:30 a.m. • Transformational Metaphors 1.0 elimination of bias credit applied for Paul Godfrey, MSBA President Madge S. Thorsen; Law Offices of Madge S. Thorsen; rewarding educational experience. Aleida O. Conners; Cargill, Inc.; Wayzata SUNRISE SESSIONS Tom Nelson, Incoming MSBA President Minneapolis Roger A. Maldonado; Faegre Baker Daniels LLP; This year’s convention combines thoughtful presentations on the legal profession Minneapolis and “critical conversations” about timely issues with important legal updates and • Cheers and Jeers: Expert Reviews of 12:45 – 1:15 p.m. -

![State V. Brown, 2021-Ohio-1249.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1941/state-v-brown-2021-ohio-1249-3551941.webp)

State V. Brown, 2021-Ohio-1249.]

[Cite as State v. Brown, 2021-Ohio-1249.] COURT OF APPEALS RICHLAND COUNTY, OHIO FIFTH APPELLATE DISTRICT STATE OF OHIO JUDGES: Hon. Craig R. Baldwin, P. J. Plaintiff-Appellee Hon. John W. Wise, J. Hon. Patricia A. Delaney, J. -vs- Case No. 2020 CA 0054 EDWARD BROWN Defendant-Appellant O P I N I O N CHARACTER OF PROCEEDING: Criminal Appeal from the Court of Common Pleas, Case No. 2019 CR 0933 JUDGMENT: Affirmed DATE OF JUDGMENT ENTRY: April 9, 2021 APPEARANCES: For Plaintiff-Appellee For Defendant-Appellant GARY BISHOP TODD W. BARSTOW PROSECUTING ATTORNEY 261 West Johnstown Road JOSEPH C. SNYDER Suite 204 ASSISTANT PROSECUTOR Columbus, Ohio 43230 38 South Park Street Mansfield, Ohio 44902 Richland County, Case No. 2020 CA 0054 2 Wise, J. {¶1} Defendant-Appellant Edward Brown (“Appellant”) appeals his conviction in the Richland County Court of Common Pleas for one count of Escape, in violation of R.C. 2921.34. Appellee is the State of Ohio. The relevant facts leading to this appeal are as follows. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS AND CASE {¶2} On March 10, 2017, Appellant entered a plea of guilty to Robbery, a felony of the second degree, in the Richland County Court of Common Pleas and was sentenced to two years in prison. {¶3} On October 15, 2018, Appellant was released from prison. The next day Officer Mayer went over the rules Appellant must follow while on post release control. The rules included that Appellant must participate in the Reentry Court Program in Richland County. Officer Mayer warned Appellant that if he left the EXIT program without approval, it could result in criminal charges. -

Alaska Justice Forum 3(1), January 1979

Alaska Justice Forum ; Vol. 3, No. 1 (January 1979) Item Type Journal Authors UAA Criminal Justice Center; Trivette, Samuel H.; Lederman, Sema Citation Alaska Justice Forum 3(1), January 1979 Publisher Criminal Justice Center, University of Alaska Anchorage Download date 29/09/2021 14:40:01 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/10825 IN THIS ISSUE· Ala1sl(;1 • Carlson's Ruling • Parole Guidelines .J11sti�e • Check Program 1� tt 1· 11111 Vol. 3, No. 1 January 1979 Carlson's Ruling on Guns AS 12.15.080 MEANS TO EFFECT RESISTED ARREST. If the person being arrested either flees or forcibly resists after notice of intention to make the arrest, the peace officer may use all the necessary and proper means to effect the arrest. On Nov. 24, Anchorage Superior interpreted by Judge Carlson, the su Constitution, Judge Carlson found it logi Court Judge Victor D. Carlson declared preme court said state statutes require a cal to extent it to a determination of the AS 12.15.080 unconstitutional to the ex finding of necessity before a homicide reasonableness of a seizure (or arrest) as tent that it permits a peace officer to use can be considered justified. A mere show well. deadly force to apprehend a suspect who ing that a suspect has committed a felony Thus, confronted with the necessity to is not a threat to the life of the officer, a is not sufficient to support a finding of determine if the seizure, or arrest in this bystander, a victim or any other person. necessity where deadly force was used case, was unreasonable due to the use of This ruling was in response to a unless a dangerous situation exists. -

United States V. Brown Page 2

RECOMMENDED FOR FULL-TEXT PUBLICATION Pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 206 File Name: 06a0184p.06 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT _________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, X Plaintiff-Appellee, - - - No. 05-5437 v. - > , DOIS EDWARD BROWN, - Defendant-Appellant. - N Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky at Pikeville. No. 04-00009—David L. Bunning, District Judge. Submitted: April 26, 2006 Decided and Filed: May 31, 2006 Before: GUY, DAUGHTREY, and CLAY, Circuit Judges. _________________ COUNSEL ON BRIEF: Stephen W. Owens, STEPHEN W. OWENS LAW OFFICE, Pikeville, Kentucky, for Appellant. Charles P. Wisdom, Jr., ASSISTANT UNITED STATES ATTORNEY, Lexington, Kentucky, for Appellee. _________________ OPINION _________________ RALPH B. GUY, JR., Circuit Judge. Defendant Dois Edward Brown appeals from the denial of his motion to suppress evidence obtained as a result of a warrantless entry into his home by a police officer responding to the reported activation of his home security system. Having preserved the issue by entering a conditional plea of guilty, defendant argues that the district court erred in finding (1) that the officer’s entry into the basement was justified under the exigent circumstances exception to the warrant requirement, and (2) that the officer’s entry into the interior room of the basement did not exceed the scope of the exigency. In that interior room, the officer found approximately 176 marijuana plants in plain view. After review of the record and the arguments presented on appeal, we affirm. 1 No. 05-5437 United States v. Brown Page 2 I. After the marijuana was discovered in defendant’s basement on April 7, 2004, police secured the premises and obtained a search warrant. -

See Superior Court Iop 65.37 Commonwealth Of

J. S71002/15 NON-PRECEDENTIAL DECISION – SEE SUPERIOR COURT I.O.P. 65.37 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA : IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF : PENNSYLVANIA v. : : NATHAN EDWARD BROWN, : No. 885 WDA 2014 : Appellant : Appeal from the Judgment of Sentence, December 16, 2013, in the Court of Common Pleas of Allegheny County Criminal Division at No. CP-02-CR-0000658-2013 BEFORE: FORD ELLIOTT, P.J.E., SHOGAN AND OTT, JJ. MEMORANDUM BY FORD ELLIOTT, P.J.E.: FILED FEBRUARY 19, 2016 Nathan Edward Brown appeals from the judgment of sentence of December 16, 2013, following his conviction of drug charges. We affirm the convictions, but vacate and remand for re-sentencing. On December 12, 2012, the Pennsylvania Bureau of Probation and Parole declared [appellant] delinquent in his parole and placed him on absconder status. On January 8, 2013, a state parole agent and local police went to [appellant]’s registered residence because of his parole status and an active warrant for his arrest.[1] Once at the home, [appellant]’s sister allowed law enforcement inside. The sister said [appellant] was in his bedroom and the agent and the police went to the room. Upon entering the room, [appellant] was placed in handcuffs for officer safety. [Appellant] said a gun 1 The arrest warrant was based on an allegation that in the early morning hours of December 23, 2012, appellant robbed Ashley Munda (“Munda”) and Sandra Leski (“Leski”) at gunpoint. J. S71002/15 was in a book bag under the bed.[2] The police found the bag and inside it a .38 caliber revolver along with 27 stamp bags of heroin.