Chapter 7 Uday Shankar Style of Creative Dance – The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Chapter 1 Uday Shankar and Locating Modernity

CHAPTER 1 UDAY SHANKAR AND LOCATING MODERNITY In 1920, a twenty year old, handsome Indian student arrived in London to study painting at the Royal College of Art. Three years later, he made his debut at Covent Garden alongside the legendary Russian ballet dancer, Anna Pavlova, although—quite remarkably—until a few months earlier, he had little to no dance experience. His audiences in England, France, and the United States nevertheless thought he was very talented at what he did. The dancer invented a new style of dance, which purportedly represented Indian culture; his dance looked “foreign” enough that nobody doubted his claim. In the late 1920s, the dancer returned to India, and demonstrated his new style to his fellow compatriots. Most of his compatriots did not care for this new style, but a few prominent figures encouraged him to continue with what he was doing. His family and friends also supported him; some of them even joined his dance troupe as dancers and musicians, including his youngest brother, twenty years his junior. The troupe then returned to Paris. Meanwhile, India was nearing the end of its dramatic transition from a British imperial colony to a newly independent nation. When the dancer returned to settle in India in the late 1930s, he immersed himself in the current debates over India’s future identity and culture. Most people, who believed the essence of Indian culture could be found in its ancient traditions, were looking to the past for the “real” definition of national culture and identity. The dancer, however, proposed that his invented style and eclectic approach to art defined India’s culture instead. -

Chapter 1 Uday Shankar: an Overview of the Period

CHAPTER 1 UDAY SHANKAR: AN OVERVIEW OF THE PERIOD BETWEEN 1900 – 1960 Given that the focus of the thesis is the period from 1960 to 1977, this overview of Uday Shankar’s life from 1900 – 1960 is primarily based on Mohan Khokar’s book, His Dance His Life – A Portrait of Uday Shankar1, the write up published in the name of Uday Shankar in the Souvenir of Shankarscope in 1970, titled My Love for Dance ,2 and a televised interview of Uday Shankar with Shambhu Mitra on DD Bharati3. The researcher is well aware of the limitations that this might present. The two most evident ones being – the biography of Uday Shankar by Mohan Khokar is in many instances incorrect, inaccurate and inadequate for the period 1960 – 1977, therefore the veracity of the biography of Shankar’s early life also remains suspect, all the more so as Khokar does not use any citations, nor does he state the sources of his information in many a case. Nonetheless, this appears to be the most comprehensive book written on Uday Shankar’s life and works till date, and therefore the researcher has used this as a base for the period between 1900 – 1960. The second limitation arises from the usage of the write-up published in the souvenir, and Uday Shankar’s interview as the researcher is well aware that the content of this write-up and interview is what Uday Shankar wanted in terms of information dissemination to his audience and therefore is more 1 Mohan Khokar, His Dance His Life – A Portrait of Uday Shankar (New Delhi: Himalayan Books, 1983) 2 Uday Shankar, “My Love for Dance,” Souvenir of Shankarscope (1970) 3 An interview of Uday Shankar by Shambhu Mitra on DD Bharati, accessed April 28, 2019, url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JHq-uBio5vE&t=14s for purposes of publicity. -

India Dance Brochure

About the Mamata Shankar Ballet Troupe: Florence High School’s Creative Writing Program teaches students to write for The Group follows the style evolved by Uday Shankar, which has the inherent grammar of Classical Indian dance and yet is innovative, contemporary and not shackled with the moors of rigid classicism. publication. Students write poems, short stories, essays, and one-act plays which The graceful body movements are blended with the idiom of vibrant folk dances of India to attain a are entered into local, state, and national writing competitions. Creative Writing statuesque quality of lyricism. The group believes that dance inculcates the feeling of love & compassion, students also write, edit, design, and publish Signatures, Florence High School’s gives a meaningful dimension to human emotions, and binds the mind and heart of the youth to the award-winning literary-arts magazine. cultural heritage and tradition. About Mamata Shankar: The mission of the Bengali Association of Huntsville is to educate the communi- Mamata Shankar is the Principal of the institution. She is an accomplished dancer, choreographer, and an ty about the culture and heritage of Bengal and its neighboring regions through actress. She has trained in Bharatanatyam, Manipuri, Kathakali, and the Uday Shankar style of dance. She educational, cultural, and recreational activities. is the daughter of Uday and Amala Shankar, wife of Chandrodoy Ghosh, niece of Pt. Ravi Shankar and sister of Ananda Shankar. Shoals India & South Asian Association (SISAA) is a non-profit organization About Chandrodoy Ghosh: based in the Shoals. SISAA’s primary mission is to enhance awareness about Chandrodoy Ghose is the Founder-Director of MAMATA SHANKAR BALLET TROUPE. -

Department of Public Relations, Chandigarh Administration Press Note

Department of Public Relations, Chandigarh Administration www.chandigarh.gov.in Press Note Chandigarh February 24: Department of Cultural Affairs, UT, Chandigarh is going to organize Chandigarh Dance Festival from 25 to 28 February at Tagore Theater at 7 pm daily. The following groups will perform:- 25th February 2013 Performance by Ganesa Natyalaya of Guru Saroj Vaidyanathan from Delhi. SAROJ VAIDYANATHAN Shrimati Saroj Vaidyanathan took her initial training in Bharatanayan under Shrimati Lalitha at the Saraswati Gana Nilayam in Chennai. She was later a student of the well known guru Kattumannar Muthukumaran Pillai of Thanjavur. She also studied Camatic music under Professor P. Sambamoorthy at Madras University and obtained a D.Litt in dance from the Indira Kala Sangeet Viswavidyalaya, khairagarh. Shrimati Saroj Vaidyanathan is well established today among the leading Bharatanayam teachers of the country. She is the founder director of Ganesa Natyalaya, a dance institution in Delhi where she has trained a large number of young dancers. Some of her students are among the leading artists of the younger generation. She is the recipient of seven honours including the Padma Shri given by the government of India in 2002 and recently she has been conerred with Padam Bhushan Award by Government of India. 26th February 2013 Performance by Gunjan Dance Academy of Ms. Meera Dass from Cuttack MEERA DASS At a tender age of eight, Meera had started training with Bandha Nata, an extremely acrobatic dance form in Anandapur, Keonjhar, Orissa. Meera Das was mesmerized and her eyes filled a with new future, when she saw the Odissi dance performance of Smt. -

Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016

All Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016 Yea Sub Artist Name Field Category r Category Prabhakar Karekar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Padma Talwalkar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Koushik Aithal - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Yuva Puraskar 6 Yashasvi 201 Sirpotkar - Yuva Music Hindustani Vocal 6 Puraskar Arvind Mulgaonkar - 201 Music Hindustani Tabla Akademi 6 Awardee Yashwant 201 Vaishnav - Yuva Music Hindustani Tabla 6 Puraskar Arvind Parikh - 201 Music Hindustani Sitar Akademi Fellow 6 Abir hussain - 201 Music Hindustani Sarod Yuva Puraskar 6 Kala Ramnath - 201 Akademi Music Hindustani Violin 6 Awardee R. Vedavalli - 201 Music Carnatic Vocal Akademi Fellow 6 K. Omanakutty - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Neela Ramgopal - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Srikrishna Mohan & Ram Mohan 201 (Joint Award) Music Carnatic Vocal 6 (Trichur Brothers) - Yuva Puraskar Ashwin Anand - 201 Music Carnatic Veena Yuva Puraskar 6 Mysore M Manjunath - 201 Music Carnatic Violin Akademi 6 Awardee J. Vaidyanathan - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee Sai Giridhar - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee B Shree Sundar 201 Kumar - Yuva Music Carnatic Kanjeera 6 Puraskar Ningthoujam Nata Shyamchand 201 Other Major Music Sankirtana Singh - Akademi 6 Traditions of Music of Manipur Awardee Ahmed Hussain & Mohd. Hussain (Joint Award) 201 Other Major Sugam (Hussain Music 6 Traditions of Music Sangeet Brothers) - Akademi Awardee Ratnamala Prakash - 201 Other Major Sugam Music Akademi -

Adobe Photoshop

MARCH 2021 Vol 45, Issue No. 1111 womansera.com BUILDS HAPPY HOMES 5 Articles 618 27 INTIMACY ISSUES CURD: THE MIRACLE FOOD! DATE OF MARRY VIRTUAL REALITY OR RAMA CH0UHAN RAMZI NIDHI JAIN CYBERSEX A. KARTIKEYAN 36 THE DISTINCTLY 53 EMPATHY IN MAJESTIC MAYFAIR HOLISTIC SPECIAL HOTELS AND RESORTS EDUCATION RAMA 40 LOVE IS NOT ENOUGH 55 GREEN AND ZERO DR. SANJAY TEOTIA WASTE : PUSH FOR 14 SUSTAINABLE BEAUTY SELF-MADE FEMALE 44 NAAD WELLNESS- SONAL BHATIA BEAUTY MOGUL AYURVEDA, NATUROPATHY, YOGA 64 26TH KIFF IN 2021 KHUSHBOO JAIN SUDIPTO MULLICK 48 DEAL WITH 66 WHAT’S YOUR IMPERFECTIONS! SEXUAL SIDE? BUSHRA HUSSAIN KHAN DEEPSHIKHA PANDEY 51 FISH SPA THE 68 “LEARNED HARMFUL EFFECTS OF OPTIMISM” NEW FAMILY FAVORITE! SUJATHA RAO THIS PEDICURE ● New family favorite ● Chicken taco soup Cookery MANEKA SANJAY GANDHI 72 YOUNG LOVE OR ● Caribbean style steamed fish INFATUATION? ● Vgrilled vegetable chicken kebabs HIMSHIKHA SHUKLA ● Slow cooked chicken stew ● Mexican style stuffed peppers 80 HOMELESS TEENS! ● Zucchini pizza RAMA ● Gluten-free tomato pasta 34 ● Brussels sprouts with honey musard chicken TAKE IT HIGH 90 MEDITATION ● DISHA SHARMA One-pot chicken soup with M. VINAYAK kale and white beans ● Bell pepper zucchini 94 FOOD HABITS FOR chicken stir-fry YOUNG TEENS HIMSHIKHA SHUKLA 96 WHY SHOULD BOYS HAVE ALL THE FUN! HIMSHIKHA SHUKLA 84 100 BEEKEEPING IN INDIA MANEKA SANJAY GANDHI 104 STAY YOUNG SUJATHA RAO 32 TODDLER TRENDS 43 PERSONAL PROBLEMS 50 BEAUTY QUERIES 71 TEENACHE 75 HE DIDN’T SPARE ME (POEM) 83 I AM PREGNANT 99 YOUR BODY 8 103 CHILD CHALLENGES Fiction 111 KITCHEN QUERIES CINEPLEX 60 JUST AN EXPERIENCE 92 TRICKING A TEA LOVER! BINAY PATHAK MUNIZA TARIQ 76 SONGS OF SPRING 108 TIME PAYS Features SOMEETA DAS NAUSHAD VALIYAKATH Editor, Printer & Publisher OFFICES DIVESH NATH Mumbai: 1704, Lodha Supremus, Dr E Moses Marg, Worli Naka, Published on behalf of Delhi Printing & Worli, Geeta Talkies Building, Publishing Co. -

Answered On:09.08.2000 Increase in Indian Cultural Centres P.D

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA EXTERNAL AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:2685 ANSWERED ON:09.08.2000 INCREASE IN INDIAN CULTURAL CENTRES P.D. ELANGOVAN Will the Minister of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government have any plan to increase the cultural Centres abroad from the present 14; (b) if so, the details thereof; (c) the details of their role in the promotion of India`s cultural Heritage; (d) the details of the programmes conducted last year by the ICCR within and outside India and the scholars/artists who visited abroad during the last three years till dated; and (e) the details of the future events on anvil and the tentative itinerary of such events that will promote and propagate Indian Heritage abroad? Answer MINISTER OF STATE FOR EXTERNAL AFFAIRS (SHRI AJIT KUMAR PANJA) (a) Yes Sir, (b) The Government has decided to open a Cultural Centre in Washington (USA). There are in addition several other proposals from various Indian Missions abroad which are currently under examination. (c) The activities of the 14 Indian Cultural Centres currently in existence reflects the needs of the local population. Their activities include the organisation of talks, lectures, exhibitions of visual arts, essay competitions, performances of dance & music, staging of plays, screening of Indian films, publication of news bulletins etc. Additionally, in most of the Cultural Centres classes in various aspects of Indian culture such as music, dance, Hindi language and yoga are being conducted. The Centres also maintain libraries, reading rooms and audio-video facilities for visitors. Apart from organising their own activities, the Indian Cultural Centres provide support to the respective Indian Missions for coordinating various cultural activities.T hese Centres develop and maintain contacts with local citizens particularly students, teachers, academicians, opinion makers and cultural personalities to project a holistic picture of India`s rich and diverse cultural heritage. -

RÉTROSPECTIVE DU CINÉMA INDIEN POPULAIRE Et

Direction de la communication DOSSIER DE PRESSE VOUS AVEZ DIT BOLLYWOOD ! RÉTROSPECTIVE DU CINÉMA INDIEN POPULAIRE et www.centrepompidou.fr VOUS AVEZ DIT BOLLYWOOD ! RÉTROSPECTIVE DU CINÉMA INDIEN POPULAIRE 4 FEVRIER – 1er MARS 2004 ET 17 MARS – 19 AVRIL 2004 CINEMA 1 (NIVEAU 1), CINEMA 2 (NIVEAU –1) DDirection sommaire de la communication 75 191 Paris cedex 04 responsable du pôle presse I. COMMUNIQUE DE PRESSE page 2 Carole Rio-Latarjet chargée des relations presse Albane Jouis-Maucherat II. VOUS AVEZ DIT « BOLLYWOOD » ! page 4 téléphone par Nadine Tarbouriech 00 33 (0)1 44 78 13 81 télécopie III PROGRAMMATION ET SYNOPSIS DES FILMS page 6 00 33 (0)1 44 78 13 02 mél IV. CALENDRIER DES PROJECTIONS page 29 albane.jouis-maucherat @cnac-gp.fr V. RENCONTRE ORGANISEE PAR LES FORUMS DE SOCIETE La « résistance » de Bollywood ? page 38 VI. EVENEMENTS AUTOUR DE LA MANIFESTATION page 40 VII. LISTE DES PHOTOS DISPONIBLES POUR LA PRESSE page 48 VIII. REMERCIEMENTS page 52 IX. INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES page 53 VOUS AVEZ DIT BOLLYWOOD ! RÉTROSPECTIVE DU CINÉMA INDIEN POPULAIRE 4 FEVRIER – 1er MARS 2004 ET 17 MARS – 19 AVRIL 2004 CINEMA 1 (NIVEAU 1), CINEMA 2 (NIVEAU –1) Direction Pour la première fois en France, une grande rétrospective consacrée à la cinématographie de la communication indienne populaire est proposée par les Cinémas du Centre Pompidou. 75 191 Paris cedex 04 responsable du pôle presse er Carole Rio-Latarjet Pensée en deux temps, la manifestation rend d’abord hommage, du 4 février au 1 mars 2004, chargée des relations presse aux auteurs des grands classiques en noir et blanc des années 50 considérées comme l’âge Albane Jouis-Maucherat d’or des studios indiens : Guru Dutt, Raj Kapoor, Bimal Roy, Mehboob Khan, V. -

GK-Tornado CDS II 2020 & Other Defence Exams

GK-Tornado CDS II 2020 & Other Defence Exams Dear Aspirants, This GK Tornado is a complete docket of important Current Affairs news and events that occurred in last 5 months. This file is important and relevant for all competitive exams like CDS, CAPF and Other Exams. National & International September 1. Mustapha Adib has been appointed as the Prime July 2022. She succeeds Rakesh Asthana (IPS) who was Minister of Lebanon. appointed as the Director-General of Border Security Note: He was Lebanon's ambassador to Germany. Force (BSF) on 17th August 2020. Mustapha Adib was named by four former prime 6. S Krishnan has been appointed as the Managing ministers on the eve of binding consultations between Director (MD) and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the president and parliamentary blocs on their choice Punjab and Sindh Bank for the post. Note: Prior to this appointment, he was an Executive Director at Canara Bank.He will replace S Harishankar, 2. Matthew Hayden has been appointed as the trade the current MD and CEO of Punjab & Sind Bank. envoy to India by Australian government along with 7. Murali Ramakrishnan has been appointed as the Indian-origin politician Lisa Singh for advancing Managing Director and CEO of the South Indian Bank. business ties with India. Note: Ramakrishnan had retired from ICICI Bank as Note: Three new appointments to the board of the Senior General Manager at Strategic Project Group on Australia-India Council were announced. Lisa Singh, May 30, 2020, and joined the South Indian Bank as an former Labor Party Senator from Tasmania, would be advisor on July 1, 2020.He represented the bank in the the Deputy Chair. -

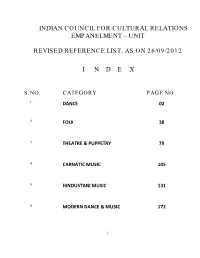

Unit Revised Reference List, As on 26/09/2012 I

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT – UNIT REVISED REFERENCE LIST, AS ON 26/09/2012 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 38 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 79 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 105 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 131 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 172 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 26/09/2012 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 19 4. KATHAKALI 20 – 21 5. KRISHNANATTAM 22 6. KUCHIPUDI 23 – 25 7. KUDIYATTAM 26 8. MANIPURI 27 – 28 9. MOHINIATTAM 29 – 30 10. ODISSI 31 – 35 11. SATTRIYA 36 12. YAKSHAGANA 37 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 26/09/2012 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) (Up) 2007 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 03.05.1998 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 28.10.1994 (Up) August 2005 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi (Up) 28.10.1994 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 03.05.1998 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 03.05.1998 15. Narayanan Kalanidhi 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika (Up) 28.10.1994 20. Sarabhai Mrinalini 21. Saroja M K 22. Sarukkai Malavika 23. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 28.10.94 (Up)3.05.1998 24. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 25. Srinivasan Kanaka 26. Subramanyam Padma 27. -

Dancer Uday Shankar: Integrating

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. DANCER UDAY SHANKAR: INTEGRATING EAST AND WEST by Jayantee Paine submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Science of the American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Performing Arts, Dance Signature of Committee Members: Chair ‘ Nmrna Prevotsr~p y r iA juxJL, Brupe C.