Unit 6 Carbohydrates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Metal Chlorides on Glucose Mutarotation and Possible Implications on Humin Formation

Reaction Chemistry & Engineering Effect of Metal Chlorides on Glucose Mutarotation and Possible Implications on Humin Formation Journal: Reaction Chemistry & Engineering Manuscript ID RE-COM-10-2018-000233.R1 Article Type: Communication Date Submitted by the 28-Nov-2018 Author: Complete List of Authors: Ramesh, Pranav; Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, Chemical and Biochemical Engineering Kritikos, Athanasios; Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, Chemical and Biochemical Engineering Tsilomelekis, George; Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, Chemical and Biochemical Engineering Page 1 of 5 ReactionPlease doChemistry not adjust & Engineering margins Journal Name COMMUNICATION Effect of Metal Chlorides on Glucose Mutarotation and Possible Implications on Humin Formation a a a Received 00th January 20xx, Pranav Ramesh , Athanasios Kritikos and George Tsilomelekis * Accepted 00th January 20xx DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x www.rsc.org/ An in-situ Raman spectroscopic kinetic study of the glucose suggested that the possible changes in the anomeric mutarotation reaction is presented herein. The effect of metal equilibrium especially via the stabilization of the α-anomer of chlorides on the ease of ring opening process is discussed. It is glucose, might be responsible for improved selectivity towards 7, 8 shown that SnCl4 facilitates the mutarotation process towards the fructose . This also agrees with the concept of anomeric β-anomer extremely fast, while CrCl3 appears to promote the specificity of enzymes; for instance, immobilized D-glucose formation of the α-anomer of glucose. Infrared spectra of humins isomerase has shown ~40% and ~110% higher conversion rates prepared in different Lewis acids underscore the posibility of starting with α–D-glucose as compared to equilibrated glucose multiple reaction pathways. -

Structural Features

1 Structural features As defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry gly- cans are structures of multiple monosaccharides linked through glycosidic bonds. The terms sugar and saccharide are synonyms, depending on your preference for Arabic (“sukkar”) or Greek (“sakkēaron”). Saccharide is the root for monosaccha- rides (a single carbohydrate unit), oligosaccharides (3 to 20 units) and polysac- charides (large polymers of more than 20 units). Carbohydrates follow the basic formula (CH2O)N>2. Glycolaldehyde (CH2O)2 would be the simplest member of the family if molecules of two C-atoms were not excluded from the biochemical repertoire. Glycolaldehyde has been found in space in cosmic dust surrounding star-forming regions of the Milky Way galaxy. Glycolaldehyde is a precursor of several organic molecules. For example, reaction of glycolaldehyde with propenal, another interstellar molecule, yields ribose, a carbohydrate that is also the backbone of nucleic acids. Figure 1 – The Rho Ophiuchi star-forming region is shown in infrared light as captured by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Explorer. Glycolaldehyde was identified in the gas surrounding the star-forming region IRAS 16293-2422, which is is the red object in the centre of the marked square. This star-forming region is 26’000 light-years away from Earth. Glycolaldehyde can react with propenal to form ribose. Image source: www.eso.org/public/images/eso1234a/ Beginning the count at three carbon atoms, glyceraldehyde and dihydroxy- acetone share the common chemical formula (CH2O)3 and represent the smallest carbohydrates. As their names imply, glyceraldehyde has an aldehyde group (at C1) and dihydoxyacetone a carbonyl group (at C2). -

Mutarotation

13 Mutarotation The α and β anomers are diastereomers of each other and usually have different specific rotations. A solution or liquid sample of a pure α anomer will rotate plane polarised light by a different amount and/or in the opposite direction than the pure β anomer of that compound. The optical rotation of the solution depends on the optical rotation of each anomer and their ratio in the solution. For example, if a solution of β-D-glucopyranose is dissolved in water, its specific optical rotation will be +18.7°. Over time, some of the β-D-glucopyranose will undergo mutarotation to become α-D-glucopyranose, which has an optical rotation of +112.2°. Thus the rotation of the solution will increase from +18.7° to an equilibrium value of +52.7° as some of the β form is converted to the α form. The equilibrium mixture is actually about 64% of β-D-glucopyranose and about 36% of α-D-glucopyranose, though there are also traces of the other forms including furanoses and open chained form. The α anomer is the major conformer, although somewhat controversially; this is due to the anomeric effect with the stabilization energy provided by n–σ* hyperconjugation. The observed rotation of the sample is the weighted sum of the optical rotation of each anomer weighted by the amount of that anomer present. 14 Therefore, one can use a polarimeter to measure the rotation of a sample and then calculate the ratio of the two anomers present from the enantiomeric excess, as long as one knows the rotation of each pure anomer. -

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Studies of Glucose Mutarotation by Using a Portable Personal Blood Glucose Meter Carlos Eduardo Perles* and Pedro Luiz Onófrio Volpe

Acta Chim. Slov. 2009, 56, 209–214 209 Short communication Thermodynamic and Kinetic Studies of Glucose Mutarotation by Using a Portable Personal Blood Glucose Meter Carlos Eduardo Perles* and Pedro Luiz Onófrio Volpe Instituto de Química, Universidade Estadual de Campinas – UNICAMP, CP. 6154 CEP. 13084-971, Campinas, SP – Brazil * Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +55 (19) 3521-3091 Received: 28-08-2008 Dedicated to Professor Josef Barthel on the occasion of his 80th birthday Abstract A thermodynamic and kinetic study of the mutarotation reaction of D-glucose in aqueous solution was carried out using a portable personal blood glucose meter. This physical chemical experiment is proposed as an alternative to classical po- larimetry. The glucose meter allows the indirect monitoring of the mutarotation process in water, by using an enzymatic redox reaction. The test strips of the glucose meter contain glucose dehydrogenase which converts β-D-glucose into D- glucolactone. This reaction selectively converts glucose and generates an electrical current in the glucose meter which is proportional to the glucose concentration. This experiment allows the teacher to explore the kinetics and thermodynamics of the mutarotation of D-glucose and, moreover, the stereospecificity of enzymatic reactions. Keywords: Glucose, mutarotation, blood glucose meter 1. Introduction are present in a cyclic form in solution, with a very small amount of the acyclic form (∼0.01%)2, 3. The mutarotation Glucose is a polyhydroxy aldehyde belonging to the is a dynamic process resulting from a chemical reaction chemical class of carbohydrates. It is the most abundant that promotes the change between the forms α- and β-D- and most important carbohydrate in nature, since the me- glucose in solution, which has a pseudo-first order reac- tabolism of a majority of living species is based on the tion kinetics in aqueous solutions. -

Quantitation of Carbohydrate Monomers and Dimers by Liquid Chromatography Coupled with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry T

Carbohydrate Research 468 (2018) 30–35 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Carbohydrate Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/carres Quantitation of carbohydrate monomers and dimers by liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry T ∗ Krista A. Barzen-Hanson1,2, Rebecca A. Wilkes2, Ludmilla Aristilde Department of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 14853, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: As remnants of plant wastes or plant secretions, carbohydrates are widely found in various environmental Liquid chromatography matrices. Carbohydrate-containing feedstocks represent important carbon sources for engineered bioproduction Mass spectrometry of commodity compounds. Routine monitoring and quantitation of heterogenous carbohydrate mixtures requires Glucose fast, accurate, and precise analytical methods. Here we present two methods to quantify carbohydrates mixtures Monosaccharides by coupling hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization high-resolution mass Disaccharides spectrometry. Method 1 was optimized for eleven different carbohydrates: three pentoses (ribose, arabinose, xylose), three hexoses (glucose, fructose, mannose), and five dimers (sucrose, cellobiose, maltose, trehalose, lactose). Method 1 can monitor these carbohydrates simultaneously, except in the case of co-elution of xylose/ arabinose and lactose/maltose/cellobiose peaks. Using the same stationary and mobile phases as in Method 1, Method 2 was developed to separate glucose and galactose, which were indistinguishable in Method 1. Both methods have low limits of detection (0.019–0.40 μM) and quantification (0.090–1.3 μM), good precision (2.4–13%) except sucrose (18%), and low mass error (0.0–2.4 ppm). Method 1 was robust at analyzing high ionic strength solutions, but a moderate matrix effect was observed. -

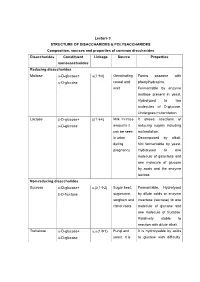

Lecture 3 STRUCTURE of DISACCHARIDES

Lecture 3 STRUCTURE OF DISACCHARIDES & POLYSACCHARIDES Composition, sources and properties of common disccharides Disaccharides Constituent Linkage Source Properties monosaccharides Reducing disaccharides Maltose -D-glucose+ (14) Germinating Forms osazone with -D-glucose cereal and phenylhydrazine. malt Fermentable by enzyme maltase present in yeast. Hydrolysed to two molecules of D-glucose. Undergoes mutarotation. Lactose -D-glucose+ (14) Milk. In trace It shows reactions of -D-glucose amounts it reducing sugars including can be seen mutarotation. in urine Decomposed by alkali. during Not fermentable by yeast. pregnancy Hydrolysed to one molecule of galactose and one molecule of glucose by acids and the enzyme lactase. Non-reducing disaccharides Sucrose -D-glucose+ ,(12) Sugar beet, Fermentable. Hydrolysed -D-fructose sugarcane, by dilute acids or enzyme sorghum and invertase (sucrase) to one carrot roots molecule of glucose and one molecule of fructose. Relatively stable to reaction with dilute alkali. Trehalose -D-glucose+ ,(11) Fungi and It is hydrolysable by acids -D-glucose yeast. It is to glucose with difficulty. stored as a Not hydrolysed by reserve food enzymes. supply in insect's hemolymph The oligosaccharides commonly encountered in nature belong to disaccharides. The physiologically important disaccharides are maltose, lactose, trehalose and sucrose. Disaccharides consist of two monosaccharides joined covalently by an O- glycosidic bond. The hydroxyl group formed as a result of hemiacetal formation is highly reactive when compared to other hydroxyl groups. This hydroxyl group present in one monosaccharide reacts with any one of the hydroxyl groups attached to C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, or C-6 of another monosaccharide to produce 1→1, 1→2, 1→3, 1→4, and 1→6 linked disaccharides. -

Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins

Examples of oligosaccharides https://quizlet.com/7700478/biochem3-carbsglycobio-flash-cards/ https://quizlet.com/86700718/biochemistry-exam-3-carbs-flash-cards/ https://quizlet.com/101806993/biochemistry-exam-3-carbs-pt-2-flash-cards/ Disaccharides Contain a Glycosidic Bond Disaccharides (such as maltose, lactose, and sucrose) consist of two monosaccharides joined covalently by an O-glycosidic bond, which is formed by dehydration (removal of H2O), a hydroxyl group of one sugar and hydrogen from OH of other sugar. This reaction form an acetal from a hemiacetal. Glycosidic bonds are readily hydrolyzed by acid but resist cleavage by base. Thus, disaccharides can be hydrolyzed to yield their free monosaccharide components by boiling with dilute acid. Maltose It is also called maltobiose or malt sugar. The disaccharide maltose contains two D-glucose residues joined by a O-glycosidic linkage between C-1 (the anomeric carbon) of one glucose residue and C-4 of the other. Because the disaccharide retains ONE free anomeric carbon maltose is a reducing sugar. The configuration of the anomeric carbon atom in the glycosidic linkage is α-(14). The glucose residue with the free anomeric carbon is capable of existing in α- and β–pyranose forms. Non-reducing reducing Lactose It is also called milk sugar. It is composed of galactose and glucose linked by is β-(14) glycosidic bond. So, galactose lose its reducing ability because the hemiacetal is converted to acetal bond, while the anomeric carbon of the glucose residue is available for oxidation and retains its reducing potential. Thus lactose is a reducing disaccharide. Its abbreviated name is Gal(14)Glc. -

Mutarotation Rates and Equilibrium of Simple Carbohydrates On-Line Number 133 Sukanya Srisa-Nga and Adrian E

Mutarotation Rates and Equilibrium of Simple Carbohydrates On-line Number 133 Sukanya Srisa-nga and Adrian E. Flood School of Chemical Engineering, Suranaree University of Technology, 111 University Avenue, Muang, Nakhon Ratchasima, 30000, Thailand, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Crystalline sugars are significant commodities in the world market, however the crystallization behaviour of many sugars is still not well known. Recently it has been shown that the mutarotation reaction of reducing sugars plays a significant role in determining the crystallization rate of these sugars, and thus it is beneficial to be able to model and predict mutarotation rates for common sugars. The mutarotation rate and equilibrium of simple carbohydrates; D-glucose, D-galactose, D-cellobiose, D-maltose, and D-turanose, in aqueous solutions were measured between 7 and 35°C, using 13C-NMR. The effects of sugar concentration and temperature on the rate of mutarotation and mutarotation equilibrium were observed. It has been found that the rate of mutarotation slightly decreases as the sugar concentration increases. The rate constant of the studied sugars follows an Arrhenius relationship with respect to temperature, and activation energies for the reactions were found from an Arrhenius plot. There are no clear correlations between the equilibrium constant and the sugar concentration or the temperature. Finally, it is quite clear that the mutarotation rate of ketose sugars is higher than the mutarotation rate of aldose sugars, and the number of rings in the structure (i.e. monosaccharide and disaccharide) does not have a significant effect on the rate of mutarotation. KEYWORDS Mutarotation, D-glucose, 13C-NMR, equilibrium composition INTRODUCTION Carbohydrates occur in all plants and animals and are the main source of energy supply in most cells. -

Fundamentals of Glycan Structure 2

Fundamentals of Glycan Structure 1 Learning Objectives How are glycans named? What are the different constituents of a glycan? How are these represented? What conformations do sugar residues adopt in solution Why do glycan conformations matter? 2 Fundamentals of Glycan Structure Carbohydrate Nomenclature Monosaccharides Structure Fisher Representation Cyclic Form Chair Form Mutarotation Monosaccharide Derivatives Reducing Sugars Uronic Acids Other Derivatives Monosaccharide Conformation Inter‐Glycosidic Bond Normal Sucrose Lactose Sequence Specificity and Recognition Branching 3 Carbohydrate Nomenclature The word ‘carbohydrate’ implies “hydrate of carbon” … Cn(H2O)m Glucose (a monosaccharide) C6H12O6 … C6(H2O)6 Sucrose (a disaccharide) C12H22O11 … C12(H2O)11 Cellulose (a polysaccharide) (C6H12O6)n… (C6(H2O)6)n Not all carbohydrates have this formula … some have nitrogen Glucosamine (glucose + amine) …. C6H13O5N… ‐NH2 at the 2‐position of glucose N‐acetyl galactosamine (galactose + amine + acetyl group) …. C8H15O6N … ‐ NHCOCH3 at the 2‐position of galactose Typical prefixes and suffixes used in naming carbohydrates Suffix = ‘‐ose’ & prefix = ‘tri‐’, ‘tetr‐’, ‘pent‐’, ‘hex‐’ Pentose (a five carbon monosaccharide) or hexose (a six carbon monosaccharide) Functional group types Monosaccharides with an aldehyde group are called aldoses … e.g., glyceraldehyde Those with a keto group are called ketoses … e.g., dihydroxyacetone 4 Monosaccharides Structure Have a general formula CnH2nOn and contain a carbonyl -

Mechanisms for the Mutarotation and Hydrolysis of the Glycosylamines and the Mutarotation of the Sugars

Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards Vol. 46 No. 2, February 1951 Research Paper 2186 Mechanisms for the Mutarotation and Hydrolysis of the Glycosylamines and the Mutarotation of the Sugars Horace S. Isbell and Harriet L. Frush A study has been made of t he kinetics of t he mutarot ation and hydrolysis reactions of L-arabinosylamine, and a m echanism has been devised to accoun t for the striking sensit ivity of t he glycosylamines to hydrolysis in a limited pH range. The concepts presented seem applicable for the interpretation of the reactions of other compounds of t he aldehyde ammonia type. 1. Introduction In the development of methods for the preparation of the amides of uronic acids [1] 1 it became necessary to determine conditions whereby the amino group II. of a l-amino-uronic amide could be hydrolyzed without alteration of the amide group. It was L-Arabinosylamine found that the rate of hydrolysis of the amino group of 1-aminomannuronic amide (I ) is extraordinarily OAc OAc H sensitive to the acidity of the reaction medium. Thus, when the compound is mixed quickly with R 2 c - 6 - 6 --6 - C H.NH.Ac one equivalent of a strong acid, hydrolysis requires I ~ 11 I I a period of many hours, but when the acid is added ~O OAc drop wise to the compound in solution, hydrolysis is III. complete in 15 min or less. Further study showed that 1-aminomannuronic amide is surprisin gly T et raacetyl-L- a rabinosylamine stable both to strong acid and to alkali, and that OR OR H hydrolysis can be effected rapidly only in the pH I I I range 4 to 7. -

Rare Sugars: Recent Advances and Their Potential Role in Sustainable Crop Protection

molecules Review Rare Sugars: Recent Advances and Their Potential Role in Sustainable Crop Protection Nikola Mijailovic 1,2, Andrea Nesler 2 , Michele Perazzolli 3,4 , Essaid Aït Barka 1 and Aziz Aziz 1,* 1 Induced Resistance and Plant Bioprotection, USC RIBP 1488, University of Reims, UFR Sciences, CEDEX 02, 51687 Reims, France; [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (E.A.B.) 2 Bi-PA nv, Londerzee l1840, Belgium; [email protected] 3 Department of Sustainable Agro-Ecosystems and Bioresources, Research and Innovation Centre, Fondazione Edmund Mach, 38010 San Michele all’Adige, Italy; [email protected] 4 Center Agriculture Food Environment (C3A), University of Trento, 38098 San Michele all’Adige, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-326-918-525 Abstract: Rare sugars are monosaccharides with a limited availability in the nature and almost unknown biological functions. The use of industrial enzymatic and microbial processes greatly reduced their production costs, making research on these molecules more accessible. Since then, the number of studies on their medical/clinical applications grew and rare sugars emerged as potential candidates to replace conventional sugars in human nutrition thanks to their beneficial health effects. More recently, the potential use of rare sugars in agriculture was also highlighted. However, overviews and critical evaluations on this topic are missing. This review aims to provide the current knowledge about the effects of rare sugars on the organisms of the farming ecosystem, with an emphasis on their mode of action and practical use as an innovative tool for sustainable agriculture. -

Unit: 4 (Carbohydrate) (Lecture-Part 3)

Course Code: CHEM3014 Course Name: Organic Chemistry V Unit: 4 (Carbohydrate) (Lecture-Part 3) For B.Sc. (Honours) Semester: VI By Dr. Abhijeet Kumar Department of Chemistry Mahatma Gandhi Central University Conversion of Open-Chain to Cyclic structure of Monosaccharide The open chain form has been found to be in equilibrium with the cyclized hemiacetal forms in case of monosaccharide. Example of cyclization of glucose has been shown below. Figure 1: Example of cyclization of glucose (Picture adapted from Chapter No. 22, ‘Organic Chemistry’ (10th edition) by T. W. G. Solomons and C. B. Fryhle.) Anomer Formation During Cyclization As it can be seen in previous slide, that during cyclization, the -OH group present at C-5 could approach to the CHO group which is planar from two different faces. After this nucleophilic addition step, a new chiral centre generates. Overall it results into the formation of two diastereomers α-D-(+)-glucopyranose and β-D-(+)- glucopyranose which differ only at one carbon centre. Anomer: These diastereomers differing only at the hemiacetal or acetal carbon are called anomers, and the hemiacetal or acetal carbon atom is called the anomeric carbon atom. Therefore after cyclization two anomers generated which are α and β anomers depending on the orientation of OH group at C1 carbon. Before we move to the next part, in first point term ‘pyranose’ was used so let’s have a look at it. O O Pyran Furan Figure 2: Structure of pyran and furan ring Pyranose: If the monosaccharide ring is six membered similar to pyran, the compound is called a pyranose.