A Defense of Jiang Rong's Wolf Totem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Green Leaves of China. Sociopolitical Imaginaries in Chinese Environmental Nonfiction

The green leaves of China. Sociopolitical imaginaries in Chinese environmental nonfiction. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Institut für Sinologie Vorgelegt von Matthias Liehr April 2013 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rudolf G. Wagner Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Barbara Mittler Table of contents Table of contents 1 Acknowledgements 2 List of abbreviated book titles 4 I. Introduction 5 I.1 Thesis outline 9 II. Looking for environmentalism with Chinese characteristics 13 II.1 Theoretical considerations: In search for a ‘green public sphere’ in China. 13 II.2 Bringing culture back in: traditional repertoires of public contention within Chinese environmentalism 28 II.3 A cosmopolitan perspective on Chinese environmentalism 38 III. “Woodcutter, wake up”: Governance in Chinese ecological reportage literature 62 III.1 Background: Economic Reform and Environmental Destruction in the 1980s 64 III.2 The narrative: Woodcutter, wake up! – A tale of two mountains, and one problem 68 III.3 The form: Literary reportage, and its role within the Chinese social imaginary 74 III.4 The subject matter: Naturescape and governance 86 IV. Tang Xiyang and the creation of China’s green avant-garde 98 IV.1 Beginnings: What nature? What man? 100 IV.2 A Green World Tour 105 IV.3 Back in China: Green Camp, and China’s new green elite 130 V. Back to the future? Ecological Civilization, and the search for Chinese modernity 144 V.1 What is “Ecological Civilization”? 146 V.2 Mr. Science or Mr. Culture to the rescue? 152 VI. The allure of the periphery: Cultural counter-narratives and social nonconformism 182 VI.1 The rugged individual in the wilderness: Yang Xin 184 VI.2 Counter-narratives and ethnicity discourse in 1980s China 193 VI.3 A land for heroes 199 VI.4 A land of spirituality 217 VII. -

Arts & Culture

ARTS & CULTURE ART P42 ART P48 IN PRINT P52 CINEMA P56 STAGE that’smags www.thebeijinger.com Novemberwww. 200 thatsbj.com8 / the Beijinger Sept. 200541 Hovering Child by American artist Fran Forman. See Preview, p46; photo courtesy of Common Ground All event listings are accurate at time of press and subject to change For venue details, see directories, p43 Send events to [email protected] by Nov 10 Nov 8-30 its over 150 art pieces of contem- porary art around the world from Wang Jie the 1960s to the present day. The By eliminating human figures in curatorial approach of the show is rt his paintings, Wang Jie’s emphasis basically chronological, showing is on clothes – our “second skin.” the historical development of the New Age Gallery (5978 9282) world of contemporary art that A Nov 8-Dec 21 parallels the trajectory of the Swiss Chinese Contemporary Art Awards bank’s tastes throughout the dec- ades. Expect big names including ART 2008 Founded in 1997 by Uli Siggs, CCAA Damien Hirst, Andy Warhol, Lucien has awarded Liu Wei this year as Freud, Jasper Johns, as well as its pick for “Best Artist” and Tseng emerging Chinese artists including Yu-chin as “Best Young Artist” (see Cao Fei, Qiu Anxiong and Xu Zhen. Feature, p44). Ai Weiwei has also National Art Museum of China been given a lifetime achievement (6401 2252/7076) award. The works of these three Until Nov 12 artists will be exhibited at the larg- Coats! est art space in 798. Ullens Center Until Jan 10: Edward Burtynsky’s China Beijing is the third stop – after for Contemporary Art (6438 6576) Berlin and Tokyo – for this exhibi- A fresh take on manufacturing art. -

The Role of Translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature : a Case Study of Howard Goldblatt's Translations of Mo Yan's Works

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Translation 3-9-2016 The role of translation in the Nobel Prize in literature : a case study of Howard Goldblatt's translations of Mo Yan's works Yau Wun YIM Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Yim, Y. W. (2016). The role of translation in the Nobel Prize in literature: A case study of Howard Goldblatt's translations of Mo Yan's works (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/tran_etd/16/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Translation at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. THE ROLE OF TRANSLATION IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE: A CASE STUDY OF HOWARD GOLDBLATT’S TRANSLATIONS OF MO YAN’S WORKS YIM YAU WUN MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 THE ROLE OF TRANSLATION IN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE: A CASE STUDY OF HOWARD GOLDBLATT’S TRANSLATIONS OF MO YAN’S WORKS by YIM Yau Wun 嚴柔媛 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Translation LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2016 ABSTRACT The Role of Translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature: A Case Study of Howard Goldblatt’s Translations of Mo Yan’s Works by YIM Yau Wun Master of Philosophy The purpose of this thesis is to explore the role of the translator and translation in the Nobel Prize in Literature through an illustration of the case of Howard Goldblatt’s translations of Mo Yan’s works. -

Replace This with the Actual Title Using All Caps

INVENTING A WOLFISH CHINA - ON JIANG RONG’S WOLF TOTEM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Dongming Shen August 2012 © 2012 Dongming Shen ABSTRACT The Wolf Totem by Jiang Rong has won great success both in and out of China. Jiang Rong criticizes Han Chinese and embraces the culture of the northern ethnic minority group, the Mongols, because of its stronger sense of competition and domination. In the epilogue of this novel, Jiang argues that the wolf totem was the most ancient totem for all Chinese people and retells Chinese history using this framework. This paper explores the background of the novel and its author, as well as supporting materials the author uses in his proposal concerning the wolf totem, and suggests that the wolf totem is a purely ideological invention of Jiang Rong. This invention reflects Jiang’s own philosophy and caters to the cultural needs of modern Chinese people. In inventing the wolf totem, the author uses historical documents, archeological findings, as well as a far-fetched bodily metaphor. However, none of this evidence is validated by scholarly research. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Dongming Shen is currently a graduate student in the Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University. Her field is East Asian Studies. Her research interests include Chinese mythology and Christianity in late imperial China. She received her undergraduate degree in English Literature and Social Science Studies at Nanjing University and her Master of Public Administration at Cornell University. -

Annu a L Repo R T 20 17–1 8

ANNUAL REPORT 2017–18 From the Director he Lieberthal Rogel Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan was established in 1961 when diplomatic relations Tbetween the PRC and the United States did not exist. With private foundation grants from the Mellon and Ford Foundations and support from the US Department of Education, the Center was part of a pioneering effort at Michigan to develop interdisciplinary centers focused on area expertise. From that time, scholars from different disciplinary backgrounds have congregated at the Center to learn from each other, to collaborate on research, and to teach students who share the same desire to acquire deep knowledge about China. More than half a century has passed, but the need for expertise and education on China is no less crucial now than it was then. The early initiatives to support Chinese Studies were motivated by Cold War concerns—conflict in Southeast Asia, the Taiwan Straits, balancing against the Soviet Union. In today’s world, China is no longer closed; its influence and global presence have expanded immensely. The US and China have learned to cooperate on many issues of global concern. However, in recent years, the competitive and conflictual side of the relationship has grown more prominent. We hear and read constantly of the trade war, the potential for a “new cold war”, and the looming University of Michigan Lieberthal-Rogel University “Thucydides Trap” when a hegemonic power is challenged by a rising upstart. In other words, what happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object. In an age that is no less anxious than the Cold War, our role in the University continues to be one that complements Michigan’s strong foundations in its schools and colleges and its impressive breadth of teaching and research. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents The Role of Library Public Art Education in Cultivating the Innovation and 1 Entrepreneurship Ability of College Students Beibei Li Research on the Cultivation of Innovative Ability of Students 5 Jian Huang Application of Apriori Association Rules Algorithm and Big Data Technology in 8 Transportation Field Zhiqi Guo, Yi Guan, Jiacong Zhao Craftsman Spirit and Jiangsu Tourism Culture Products 12 Yan Gu, Qing Zeng, Tingxuan Chen and Ximei Wei Observe Curative Effect of Functional Rehabilitation Training on Patients with Poor 16 Pulmonary Function in Different Concentrations of Negative Oxygen Ions Siqing Zhang and Yanru Zhang The Impact of Establishing Electronic Archives of Academic Integrity on Researchers' 22 Scientific Research Behavior Gang Chen and Shuping Wang Research on Negotiated Interaction in EFL Classroom Teaching 27 Xiumei Guan and Fenggang Gao Exploration and Practice of Constructing the Teaching System of Electromechanical 32 Major in Higher Vocational Education with Vocational Qualification Certificate Chen Guiyin Exploration of Production Management Practice in Civil Engineering Major 39 Yao Xu and Yinghui Lv Research on Japanese Blended Teaching Mode Based on MOOCs and Micro-lecture 43 Xuemei Zhang -I- Analysis of the Constraints of the Construction of E-Government on the Construction of 47 Service-oriented Government in China Chuanli Wei Engineering Survey Course Reform of Applied Civil Engineering Professional Talents 51 Training System Jie Liu and Feng Shan Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education Reform for Nursing Undergraduates in 55 Double Creation Era Zhe Shao Determination of Indicators and Weights of College Teaching Evaluation System Based 60 on KANO Model Xianping Gao, Xufeng Guo and Kunpeng Hu A Study on the Origin and Present Situation of Shaman Dance of Fishing and Hunting 66 Nationality Lei Ma Research on the Relationship between Debt Arrangement Structure and Corporate Value 72 Yue Geng On Studies of Burton D. -

The Chinese Film Industry: Features and Trends, 2010-2016

THE CHINESE FILM INDUSTRY: FEATURES AND TRENDS, 2010-2016 Jinuo Diao A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2020 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/19497 This item is protected by original copyright The Chinese Film Industry: Features and Trends, 2010-2016 Jinuo Diao This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at the University of St Andrews December 2019 Candidate's declaration I, Jinuo Diao, do hereby certify that this thesis, submitted for the degree of PhD, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for any degree. I was admitted as a research student at the University of St Andrews in September 2015. I received funding from an organisation or institution and have acknowledged the funder(s) in the full text of my thesis. Date 18 December 2019 Signature of candidate Supervisor's declaration I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

A Study on Translation Strategies of Culture-Loaded Words in Wolf Totem from the Perspective of Skopos Theory

Journal of Frontiers in Art Research DOI: 10.23977/jfar.2021.010313 Clausius Scientific Press, Canada Volume 1, Number 3, 2021 A Study on Translation Strategies of Culture-Loaded Words in Wolf Totem from the Perspective of Skopos Theory Fu Xinmeng Inner Mongolia University, Hohhot, 010000, China Keywords: Skopos theory, Wolf totem, Chinese culture-loaded words, Translation strategies Abstract: Skopos theory holds that translation is a complicated, arduous and purposeful human activity, and the criterion of judging it should be whether the translator has used the appropriate translation strategies to accomplish the translation skopos accurately. Therefore, due to different skopos of the translator himself, there may be multiple versions of the same source text exist for different skopos. Based on the skopos theory, this thesis aims to find a more suitable translation method for Chinese culture-loaded words by analysing the translation strategies and specific translation methods adopted by Goldblatt in the English version Wolf Totem. Through a comparative study, the author found that the two translation strategies of foreignization and domestication are often used by Goldblatt in Wolf Totem. Through the analysis of a large number of examples, the author believes that this two translation strategies can help readers to understand the source text better, to achieve the translators’ translation skopos. This discovery may provide some references for the translation of Chinese excellent literary works in the future. 1. Introduction With the rapid development of the global economy and political communication, cultural exchange as one of the aspects is becoming increasingly crucial in our everyday life. Due to different cultural backgrounds that people have, their ways of thinking, standards of conduct and values also vary from each other, and this significant difference can be reflected directly and prominently in the use of the language. -

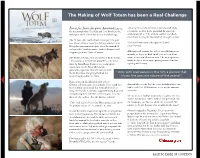

The Making of Wolf Totem Has Been a Real Challenge

The Making of Wolf Totem has been a Real Challenge Even for Jean Jacques Annaud, known following 18 months the team experienced all kinds for his animal ilms The Bear and Two Brothers, the of extreme weather in the grassland. In winter the making of Wolf Totem has been a real challenge. temperature fell to 30 C, while in summer everybody wore masks to keep the thousands of mosquitoes away. The 71-year-old French director has spent the past four years in China, mostly in Beijing and the Inner “I should have made a Mosquitoes Totem,” Mongolia autonomous region, where he trained 35 jokes Annaud. wolves with Canadian trainer Andrew Simpson and longtime producer Xavier Castano. Although well trained, the wolves are still dangerous animals, so the crew built small zoos to keep them The wolves are important characters in Wolf Totem, inside fences and electronic nets. The crew spent six a ilm based on the Chinese bestseller of the same weeks to ilm a six minute opening scene of wolves name by Jiang Rong. It traces two young men’s ighting with horses. experiences on the Inner Mongolian grasslands, especially their interactions with the wolves there. Penguin published the “Only with real wolves is this film a picture that book’s English edition in 2008. shows the genuine nature of the animal.” Many scenes in the ilm deal with wolves ighting with men and other animals. They could have Annaud also reveals that the team, including him, once been computergenerated, but Annaud insisted on had to walk 8 to 10 kilometers to set up the cameras using real wolves. -

China's Ethnic Frontiers in the Literary

HARMONY & HETEROTOPIAS: CHINA’S ETHNIC FRONTIERS IN THE LITERARY IMAGINATION by YUQING YANG A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2013 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Yuqing Yang Title: Harmony & Heterotopias: China’s Ethnic Frontiers in the Literary Imagination This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Alison Groppe Chairperson Maram Epstein Core Member Tze-Lan Sang Core Member Ina Asim Institutional Representative and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii © 2013 Yuqing Yang iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Yuqing Yang Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures June 2013 Title: Harmony & Heterotopias: China’s Ethnic Frontiers in the Literary Imagination My dissertation looks at the depiction of China’s ethnic frontiers in contemporary Chinese literature in order to examine a range of responses to the state-envisioned ideals of Harmony propagated throughout PRC history. The Confucian texts of Datong, or Great Harmony, are embedded in Maoist utopian visions for moulding the natural and human worlds in anticipation of socialist modernity; the contemporary revival of the Datong ideal expresses China’s desire to build a harmonious (hexie) society in the 21st century. In the world of fiction, China’s borderlands, home to ethnic minorities, are often conceived of as idyllic lands brimming with the type of harmony that is absent in the imperfect actuality of the political center. -

The Ecological Perspective of Chinese Eco-Film Xiaolu Wang1,*

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 515 Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2020) The Ecological Perspective of Chinese Eco-film Xiaolu Wang1,* 1Communication University of China, Beijing 100024, China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper takes Chinese eco-film as the research text, from the cultural psychology of "unity of man and nature", the attitude of "reverence for life", and the ecological appeal of "home consciousness", to observe Chinese eco-film from these three ecological perspectives. As an art style to reflect the real life, the film visualizes the ecological problems in real life into images, and transforms the conceptualized and abstract "relationship between man and nature" in human thinking into clear and perceptible life scenes. Chinese eco-film not only re-examines the relationship between man and nature from the ecological level, it also goes deep into the level of individuation to discuss the multi-faceted and complex nature of human nature, confronting people's survival and spiritual predicaments, and expressing human beings reflection and awareness in internal and external troubles. Keywords: Chinese eco-film, unity of man and nature, reverence for life, home consciousness rapid development of science and technology in the I. INTRODUCTION new century has led to new changes in the relationship From the perspective of ecology, we should first between humans and the media. The different understand what Chinese eco-film is. Chinese eco-film ecological meanings and results formed also affect our emerged in the 1980s. The research scope of eco-film in understanding of eco-film (and even the film and this paper is the feature film with ecological television form itself). -

China Perspectives, 2009/2 | 2009 Jiang Rong, Le Totem Du Loup, (Wolf Totem) Translated by Yan Hansheng and Lis

China Perspectives 2009/2 | 2009 1989, a Watershed in Chinese History? Jiang Rong, Le Totem du loup, (Wolf Totem) translated by Yan Hansheng and Lisa Carducci Paris, Bourin Editeur, 2007, 576 pp. Noël Dutrait Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4825 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4825 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2009 Number of pages: 125-127 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Noël Dutrait, « Jiang Rong, Le Totem du loup, (Wolf Totem) translated by Yan Hansheng and Lisa Carducci », China Perspectives [Online], 2009/2 | 2009, Online since 01 June 2009, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4825 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4825 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © All rights reserved Jiang Rong, Le Totem du loup, (Wolf Totem) translated by Yan Hansheng and Lis... 1 Jiang Rong, Le Totem du loup, (Wolf Totem) translated by Yan Hansheng and Lisa Carducci Paris, Bourin Editeur, 2007, 576 pp. Noël Dutrait 1 Published in China in 2004 by Changjiang wenyi chubanshe, Jiang Rong’s novel Lang tuteng (Wolf Totem) was immediately a phenomenal success. I myself witnessed this success while in China, where bookshops displayed multiple stacks of the book. Its author, Jiang Rong, the pseudonym of Lu Jiamin, was an activist in the Tiananmen Square movement in 1989; now a researcher in social sciences and the husband of Zhang Kangkang, a well-known writer, Jiang Rong maintained a mystery surrounding his identity, refusing to give interviews for several months.