Teresa L. Ebert: "Left of Desire"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexandra Kollontai and Marxist Feminism Author(S): Jinee Lokaneeta Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol

Alexandra Kollontai and Marxist Feminism Author(s): Jinee Lokaneeta Source: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 36, No. 17 (Apr. 28 - May 4, 2001), pp. 1405- 1412 Published by: Economic and Political Weekly Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4410544 Accessed: 08-04-2020 19:08 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Economic and Political Weekly This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Wed, 08 Apr 2020 19:08:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Alexandra Kollontai and Marxist Feminism To record the contradictions within the life and writings of Alexandra Kollontai is to reclaim a largely unidentified part of Marxist feminist history that attempted to extend Engel's and Bebel's analysis of women's oppression but eventually went further to expose the inadequacy of prevalent Marxist feminist history and practice in analysing the woman's question. This essay is not an effort to reclaim that history uncritically, but to give recognition to Kollontai's efforts and -

Alexandra Kollontai: an Extraordinary Person

Alexandra Kollontai: An Extraordinary Person Mavis Robertson After leaving her second husband, Pavel By any standards, Alexandra Kollontai Dybenko, she commented publicly that he was an extraordinary person. had regarded her as a wife and not as an She was the only woman member of the individual, that she was not what he needed highest body of the Russian Bolshevik Party because “I am a person before I am a in the crucial year of 1917. She was woman” . In my view, there is no single appointed Minister for Social Welfare in the statement which better sums up a key first socialist government. As such, she ingredient of Kollontai’s life and theoretical became the first woman executive in any work. government. She inspired and developed far Many of her ideas are those that are sighted legislation in areas affecting women discussed today in the modern women’s and, after she resigned her Ministry because- movement. Sometimes she writes in what of differences with the majority of her seems to be unnecessarily coy language but comrades, her work in women’s affairs was she was writing sixty, even seventy years reflected in the Communist Internationale. ago before we had invented such words as ‘sexism’. She sought to solve the dilemmas of She was an outstanding publicist and women within the framework of marxism. public speaker, a revolutionary organiser While she openly chided her male comrades and writer. Several of her pamphlets were for their lack of appreciation of and concern produced in millions of copies. Most of them, for the specifics of women’s oppression, she as well as her stories and novels, were the had little patience for women who refused to subjects of controversy. -

Salgado Munoz, Manuel (2019) Origins of Permanent Revolution Theory: the Formation of Marxism As a Tradition (1865-1895) and 'The First Trotsky'

Salgado Munoz, Manuel (2019) Origins of permanent revolution theory: the formation of Marxism as a tradition (1865-1895) and 'the first Trotsky'. Introductory dimensions. MRes thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/74328/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Origins of permanent revolution theory: the formation of Marxism as a tradition (1865-1895) and 'the first Trotsky'. Introductory dimensions Full name of Author: Manuel Salgado Munoz Any qualifications: Sociologist Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Research School of Social & Political Sciences, Sociology Supervisor: Neil Davidson University of Glasgow March-April 2019 Abstract Investigating the period of emergence of Marxism as a tradition between 1865 and 1895, this work examines some key questions elucidating Trotsky's theoretical developments during the first decade of the XXth century. Emphasizing the role of such authors like Plekhanov, Johann Baptists von Schweitzer, Lenin and Zetkin in the developing of a 'Classical Marxism' that served as the foundation of the first formulation of Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution, it treats three introductory dimensions of this larger problematic: primitive communism and its feminist implications, the debate on the relations between the productive forces and the relations of production, and the first apprehensions of Marx's economic mature works. -

“The Scourge of the Bourgeois Feminist”: Alexandra Kollontai's

AWE (A Woman’s Experience) Volume 4 Article 17 5-1-2017 “The courS ge of the Bourgeois Feminist”: Alexandra Kollontai’s Strategic Repudiation and Espousing of Female Essentialism in The oS cial Basis of the Woman Question Hannah Pugh Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/awe Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pugh, Hannah (2017) "“The cS ourge of the Bourgeois Feminist”: Alexandra Kollontai’s Strategic Repudiation and Espousing of Female Essentialism in The ocS ial Basis of the Woman Question," AWE (A Woman’s Experience): Vol. 4 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/awe/vol4/iss1/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in AWE (A Woman’s Experience) by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Author Bio Hannah Pugh is a transfer student from Swarthmore College finishing her second year at BYU. She is pursuing a double major in English and European studies—a combination she enjoys because it allows her to take an eclectic mix of political science, history, and literature courses. She’s planning to attend law school after her graduation next April. Currently, Hannah works as the assistant director of Birch Creek Service Ranch, a nonprofit organization in central Utah that runs a service- oriented, character-building summer program for teens. Her hobbies include backpacking, fly fishing, impromptu trips abroad, and wearing socks and Chacos all winter long. -

THE CHILD UNDER SOVIET LAW John N

THE CHILD UNDER SOVIET LAW JoHN N. HAzARD* MPHASIZING the importance of the family unit, Soviet legal circles are now centering their attention on laws preserving the home. Gone are the years when theoreticians argued that the family was a superannuated form of social organization, and that the child in a socialist society should be maintained and educated in mass institutions. Although political considerations may have called for such a policy in the early period of the Russian revolution due to the need of quickly overcoming the conservative influence of parents long steeped in discarded traditions, no longer does any one broach such a proposition. Today's policy of child protection and the prevention of juvenile crime is directed towards the strengthening of those organizations best fitted for the care of children. Emphasis is being laid upon the family unit, guardianship, the school, and manual labor for those children not fitted to continue in the schoolroom after the early stages. The comparatively few children who do not react to these methods of approach and become delinquents may now be held accountable under the criminal codes which have been recently revised to conform with the policy of today. Statistics studied by the Institute of Criminal Politics in Moscow, have pointed up the situation so that all may see the need for the reforms of 1935 and 1936 in the field of family and criminal law. Of the i,ooi juve- nile delinquents studied in Leningrad in 1934 and 1935, 90% spent their leisure time in an unorganized way outside the family, while only 7% of the offenders spent their recreation hours within the family circle. -

Chapter 3 Chapter 3 James April James April from Cape

Chapter 3 Chapter 3 James April James April from Cape Town, became active in the Coloured People's Congress in 1961. April underwent a brief spell of military training at Mamre in 1962, and was detained, together with Basil February in 1962 for painting political slogans, and redetained and chargedfor attending the Mamre training camp in 1963. He subsequently left the country with February for military training. April participated in the Wankie Campaign. I was born in a place called Bokmakeri, a suburb of Cape Town. It was part of a greater suburb, and it was mostly Coloureds that were living there. It was one of the units run by the city council, the housing schemes. I was born there in 1940 and I am the last of a family of seven; we were five brothers and two sisters. My father and mother migrated from elsewhere to Cape Town. My mother was from Greytown. My father left school early to work, although his mother was a teacher. My father was a labourer, working in various jobs in the production side, you know. He didn't have a lot of education, like most people from the surrounding countryside - he grew up on a farm. At that time very few people had skills. The family went through hard times during the Depression. My mother had a very English background. Her maiden name was Brian. I took the name when I was in MK - "George Brian". In those days the father was usually the breadwinner. The mother stayed at home. I grew up as an Anglican. -

The New Woman and the New Bytx Women and Consumer Politics In

The New Woman and the New Bytx Women and Consumer Politics in Soviet Russia Natasha Tolstikova, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Linda Scott, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Feminist theory first appeared in the Journal of Consumer disadvantages were carried into the post-Revolutionary world, just Researchin 1993 (Hirschman 1993, BristorandFischer 1993, Stern as they were carried through industrialization into modernity in the 1993). These three articles held in common that a feminist theoreti- West. cal and methodological orientation would have benefits for re- The last days of the monarchy in Russia were a struggle among search on consumer behavior, but did not focus upon the phenom- factions with different ideas about how the society needed to enon of consumption itself as a site of gender politics. In other change. One faction was a group of feminists who, in an alliance venues within consumer behavior, however, such examination did with intellectuals, actually won the first stage of the revolution, occur. For instance, a biannual ACR conference on gender and which occurred in February 1917. However, in the more famous consumer behavior, first held in 1991, has become a regular event, moment of October 1917, the Bolsheviks came to power, displacing stimulating research and resulting in several books and articles, in their rivals in revolution, including the feminists. The Bolsheviks the marketing literature and beyond (Costa 1994; Stern 1999; adamantly insisted that the path of freedom for women laid through Catterall, McLaran, and Stevens, 2000). This literature borrows alliance with the workers. They were scrupulous in avoiding any much from late twentieth century feminist criticism, including a notion that might suggest women organize in their own behalf or tendency to focus upon the American or western European experi- that women'soppression was peculiarly their own. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 055 500 FL 002 601 the Language Learner

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 055 500 FL 002 601 TITLE The Language Learner: Reaching His Heartand Mind. Proceedings sr the Second International Conference. INSTITUTION New York State Association ofForeign Language Teachers.; Ontario Modern LanguageTeachers' AssociatIon. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 298p.; Conference held in Toronto,Ontario, March 25-27, 1971 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS Articulation (Program); AudiolingualMethods; Basic Skills; Career Planning; *Conference Reports;English (Second Language); *Instructional ProgramDivisions; Language Laboratories; Latin; *LearningMotivation; Low Ability Students; *ModernLanguages; Relevance (Education); *Second Language Learning;Student Interests; Student Motivation; TeacherEducation; Textbook Preparation ABSTRACT More than 20 groups of commentaries andarticles which focus on the needs and interestsof the second-language learner are presented in this work. Thewide scope of the study ranges from curriculum planning to theoretical aspects ofsecond-language acquisition. Topics covered include: (1) textbook writing, (2) teacher education,(3) career longevity, (4) programarticulation, (5) trends in testing speaking skills, (6) writing and composition, (7) language laboratories,(8) French-Canadian civilization materials,(9) television and the classics, (10)Spanish and student attitudes, (11) relevance and Italianstudies, (12) German and the Nuffield materials, (13) Russian and "Dr.Zhivago," (14) teaching English as a second language, (15)extra-curricular activities, and (16) instructional materials for theless-able student. (RL) a a CONTENTS KEYNOTE ADDRESS: DR. WILGA RIVERS 1 - 11 HOW CAN STUDENTS BE INVOLVED IN PLANNING THE LANGUAGE CURRICULUM 12 - 24 TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF A LANGUAGE TEXTBOOK WRITER 25 - 38 PREPARING FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHERS: NEW EMPHASIS IN THE 70'S 39 - 52 STAMINA AND THE LANGUAGE TEACHER: WAYS IN WHICH TO ACHIEVE LONGEVITY 53 - 64 A SEQUENTIAL LANGUAGE CURRICULUM IN HIGHER EDUCATION 65 - 81 NEW TRENDS IN TESTING THE SPEAKING SKILL IN ELEM AND SEC. -

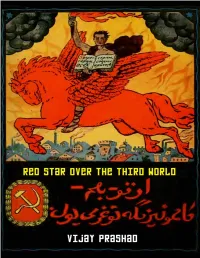

“Red Star Over the Third World” by Vijay Prashad

ALSO BY VIJAY PRASHAD FROM LEFTWORD BOOKS No Free Left: The Futures of Indian Communism 2015 The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South. 2013 Arab Spring, Libyan Winter. 2012 The Darker Nations: A Biography of the Short-Lived Third World. 2009 Namaste Sharon: Hindutva and Sharonism Under US Hegemony. 2003 War Against the Planet: The Fifth Afghan War, Imperialism and Other Assorted Fundamentalisms. 2002 Enron Blowout: Corporate Capitalism and Theft of the Global Commons, co-authored with Prabir Purkayastha. 2002 Dispatches from the Arab Spring: Understanding the New Middle East, co-edited with Paul Amar. 2013 Dispatches from Pakistan, co-edited with Madiha R. Tahir and Qalandar Bux Memon. 2012 Dispatches from Latin America: Experiments Against Neoliberalism, co-edited with Teo Balvé. 2006 OTHER TITLES BY VIJAY PRASHAD Uncle Swami: South Asians in America Today. 2012 Keeping Up with the Dow Joneses: Stocks, Jails, Welfare. 2003 The American Scheme: Three Essays. 2002 Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity. 2002 Fat Cats and Running Dogs: The Enron Stage of Capitalism. 2002 The Karma of Brown Folk. 2000 Untouchable Freedom: A Social History of a Dalit Community. 1999 First published in November 2017 E-book published in December 2017 LeftWord Books 2254/2A Shadi Khampur New Ranjit Nagar New Delhi 110008 INDIA LeftWord Books is the publishing division of Naya Rasta Publishers Pvt. Ltd. leftword.com © Vijay Prashad, 2017 Front cover: Bolshevik Poster in Russian and Arabic Characters for the Peoples of the East: ‘Proletarians of All Countries, Unite!’, reproduced from Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution, New York: Boni and Liveright Publishers, 1921 Sources for images, as well as references for any part of this book are available upon request. -

The Rise and Fall of Communism

The Rise and Fall of Communism archie brown To Susan and Alex, Douglas and Tamara and to my grandchildren Isobel and Martha, Nikolas and Alina Contents Maps vii A Note on Names viii Glossary and Abbreviations x Introduction 1 part one: Origins and Development 1. The Idea of Communism 9 2. Communism and Socialism – the Early Years 26 3. The Russian Revolutions and Civil War 40 4. ‘Building Socialism’: Russia and the Soviet Union, 1917–40 56 5. International Communism between the Two World Wars 78 6. What Do We Mean by a Communist System? 101 part two: Communism Ascendant 7. The Appeals of Communism 117 8. Communism and the Second World War 135 9. The Communist Takeovers in Europe – Indigenous Paths 148 10. The Communist Takeovers in Europe – Soviet Impositions 161 11. The Communists Take Power in China 179 12. Post-War Stalinism and the Break with Yugoslavia 194 part three: Surviving without Stalin 13. Khrushchev and the Twentieth Party Congress 227 14. Zig-zags on the Road to ‘communism’ 244 15. Revisionism and Revolution in Eastern Europe 267 16. Cuba: A Caribbean Communist State 293 17. China: From the ‘Hundred Flowers’ to ‘Cultural Revolution’ 313 18. Communism in Asia and Africa 332 19. The ‘Prague Spring’ 368 20. ‘The Era of Stagnation’: The Soviet Union under Brezhnev 398 part four: Pluralizing Pressures 21. The Challenge from Poland: John Paul II, Lech Wałesa, and the Rise of Solidarity 421 22. Reform in China: Deng Xiaoping and After 438 23. The Challenge of the West 459 part five: Interpreting the Fall of Communism 24. -

The Revolutionary Policies and Leninist Results of Bolshevik Feminism, 1917-1921

ABSTRACT The Revolutionary Policies and Leninist Results of Bolshevik Feminism, 1917-1921 Elizabeth Larson Director: Steven Jug, Ph.D. This thesis examines Russian women’s experiences during the Bolshevik Revolution and the Russian Civil War. This work identifies what women expected and what failed to happen during one of the most foundational periods of history for modern Russian women. A central figure in the work is a leading socialist women’s activist, Alexandra Kollontai, who aimed to liberate women by pressing the state to provide women economic independence. Her writings demonstrated forms of self-censorship, which signify the many hopes, which were never fulfilled. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ____________________________________________ Dr. Steven Jug, Department of History APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ____________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: ___________________________ THE REVOLUTIONARY POLICIES AND LENINIST RESULTS OF BOLSHEVIK FEMINISM, 1917-1921 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Elizabeth Larson Waco, Texas May 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . iii Introduction . 1 Chapter One: Criticizing and Theorizing the Path to Liberation . 8 Chapter Two: Mobilizing and Agitating Women Workers Toward Liberation . 21 Chapter Three: Revising and Retrenching the Narrative of Emancipation . 47 Conclusion . 64 Bibliography . 68 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my mentor, Dr. Steven Jug, for offering his wisdom, patience, support, and incredible humor throughout this honors thesis project. I would like to thank Dr. Julie deGraffenried and Ms. Eileen M. Bentsen for their willingness to serve on my panel. This thesis is dedicated to my grandmother, Mrs. -

Joseph Stalin: a Great Leader, Yet a Killer of Millions Noah Berger

1 Joseph Stalin: A Great Leader, Yet a Killer of Millions Noah Berger Junior Division Historical Paper Paper length: 2488 2 Throughout recorded time… there have been three kinds of people in the world, the High, the Middle, and the Low… The aim of the High is to remain where they are. The aim of the Middle is to change places with the High. The aim of the Low… is to… create a society in which all men are equal.1 The quote above by George Orwell examining the wheel of change of power throughout time was broken by Joseph Stalin, because he started as a peasant and eventually became a dictator. Stalin was a great leader, a hard worker, and street smart. Unfortunately, he used these abilities for immoral motives. He utilized his persuasive leadership skills to mobilize his country into the industrial age. However, he did it in a way that killed millions of his people and left a legacy of terror and death throughout Europe and the world. He broke barriers by destroying Orwell’s wheel of power, pulling off the greatest shift in government in human history. Stalin’s early life shaped his aspirations as an adult. Losif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili was born in Gori, Georgia on the eighteenth of December in 1878. He would later become the dictator of Russia. Losif’s father, Besarion Jughashvili, was a cobbler, and his mother was a washerwoman named Ketevan Geladze.2 Both of Losif’s parents gave out tough beatings. His father was an alcoholic3, while his mother swayed from affectionate to abusive regularly.4 Georgian folklore and traditions became his 1 George Orwell, 1984 (Harvill Secker, 1949), 254 2 Biography.com Editors, Joseph Stalin Biography (A&E Television Networks, 2 Apr.