Moon Prism Power!: Censorship As Adaptation in the Case of Sailor Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

The Walking Dead

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1080950 Filing date: 09/10/2020 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91217941 Party Plaintiff Robert Kirkman, LLC Correspondence JAMES D WEINBERGER Address FROSS ZELNICK LEHRMAN & ZISSU PC 151 WEST 42ND STREET, 17TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10036 UNITED STATES Primary Email: [email protected] 212-813-5900 Submission Plaintiff's Notice of Reliance Filer's Name James D. Weinberger Filer's email [email protected] Signature /s/ James D. Weinberger Date 09/10/2020 Attachments F3676523.PDF(42071 bytes ) F3678658.PDF(2906955 bytes ) F3678659.PDF(5795279 bytes ) F3678660.PDF(4906991 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD ROBERT KIRKMAN, LLC, Cons. Opp. and Canc. Nos. 91217941 (parent), 91217992, 91218267, 91222005, Opposer, 91222719, 91227277, 91233571, 91233806, 91240356, 92068261 and 92068613 -against- PHILLIP THEODOROU and ANNA THEODOROU, Applicants. ROBERT KIRKMAN, LLC, Opposer, -against- STEVEN THEODOROU and PHILLIP THEODOROU, Applicants. OPPOSER’S NOTICE OF RELIANCE ON INTERNET DOCUMENTS Opposer Robert Kirkman, LLC (“Opposer”) hereby makes of record and notifies Applicant- Registrant of its reliance on the following internet documents submitted pursuant to Rule 2.122(e) of the Trademark Rules of Practice, 37 C.F.R. § 2.122(e), TBMP § 704.08(b), and Fed. R. Evid. 401, and authenticated pursuant to Fed. -

El Cine De Animación Estadounidense

El cine de animación estadounidense Jaume Duran Director de la colección: Lluís Pastor Diseño de la colección: Editorial UOC Diseño del libro y de la cubierta: Natàlia Serrano Primera edición en lengua castellana: marzo 2016 Primera edición en formato digital: marzo 2016 © Jaume Duran, del texto © Editorial UOC (Oberta UOC Publishing, SL) de esta edición, 2016 Rambla del Poblenou, 156, 08018 Barcelona http://www.editorialuoc.com Realización editorial: Oberta UOC Publishing, SL ISBN: 978-84-9116-131-8 Ninguna parte de esta publicación, incluido el diseño general y la cubierta, puede ser copiada, reproducida, almacenada o transmitida de ninguna forma, ni por ningún medio, sea éste eléctrico, químico, mecánico, óptico, grabación, fotocopia, o cualquier otro, sin la previa autorización escrita de los titulares del copyright. Autor Jaume Duran Profesor de Análisis y Crítica de Films y de Narrativa Audiovi- sual en la Universitat de Barcelona y profesor de Historia del cine de Animación en la Escuela Superior de Cine y Audiovi- suales de Cataluña. QUÉ QUIERO SABER Lectora, lector, este libro le interesará si usted quiere saber: • Cómo fueron los orígenes del cine de animación en los Estados Unidos. • Cuáles fueron los principales pioneros. • Cómo se desarrollaron los dibujos animados. • Cuáles han sido los principales estudios, autores y obras de este tipo de cine. • Qué otras propuestas de animación se han llevado a cabo en los Estados Unidos. • Qué relación ha habido entre el cine de animación y la tira cómica o los cuentos populares. Índice -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma De Puebla

BENEMÉRITA UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE PUEBLA INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y HUMANIDADES “ALFONSO VÉLEZ PLIEGO” MAESTRÍA EN SOCIOLOGÍA EXPERIENCIA Y CULTURA JAPONESA EN IMÁGENES HISTÓRICAS MERCANTILES DEL ANIME EN MÉXICO TESIS PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE MAESTRO EN SOCIOLOGÍA PRESENTA: LIC. ALAN EUGENIO GONZÁLEZ DIRECTOR: DR. FERNANDO T. MATAMOROS PONCE PUEBLA, PUE., DICIEMBRE 2020 1 Índice Portada……………………………………………………………………………………... 1 Agradecimientos………………………………………………............................................ 4 Introducción………………………………………………………………………………... 9 Capítulo I Revisión conceptual sobre las dimensiones culturales japonesas en la conformación de identidades………………………………………………………………………………. 17 1.1 La cultura y la vida cotidiana en una sociedad………………………………………. 18 1.2 Una sociedad dominada……………………………………………………………… 38 1.3 Impulsos y deseos de los sujetos en una sociedad…………………………………… 49 Capítulo II Una puerta al pasado: Lo japonés en México como antecedente participativo en la llegada del anime………………………………………………………………………... 57 2.1 Un encuentro, antes de un México. La misión Hasekura……………………………. 59 2.2 La comisión astronómica y las migraciones japonesas……………………………… 62 2.2.1 La comisión astronómica y sus consecuencias…………………………….. 62 2.2.2 Las migraciones japonesas………………………........................................ 67 2.3 La vida durante y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial………………………….. 82 2.4 La literatura japonesa………………………………………………………………... 93 2.5 El karate en México………………………………………………………………….. 96 2.5.1 Koichi Choda Watanabe y el Karate-do -

Naoko Takeuchi

Naoko Takeuchi After going to the post-recording parties, I realized that Sailor Moon has come to life! I mean they really exist - Bunny and her friends!! I felt like a goddess who created mankind. It was so exciting. “ — Sailor Moon, Volume 3 Biography Naoko Takeuchi is best known as the creator of Sailor Moon, and her forte is in writing girls’ romance manga. Manga is the Japanese” word for Quick Facts “comic,” but in English it means “Japanese comics.” Naoko Takeuchi was born to Ikuko and Kenji Takeuchi on March 15, 1967 in the city * Born in 1967 of Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan. She has one sibling: a younger brother named Shingo. Takeuchi loved drawing from a very young age, * Japanese so drawing comics came naturally to her. She was in the Astronomy manga (comic and Drawing clubs at her high school. At the age of eighteen, Takeuchi book) author debuted in the manga world while still in high school with the short story and song writer “Yume ja Nai no ne.” It received the 2nd Nakayoshi Comic Prize for * Creator of Newcomers. After high school, she attended Kyoritsu Yakka University. Sailor Moon While in the university, she published “Love Call.” “Love Call” received the Nakayoshi New Mangaka Award for new manga artists and was published in the September 1986 issue of the manga magazine Nakayo- shi Deluxe. Takeuchi graduated from Kyoritsu Yakka University with a degree in Chemistry specializing in ultrasound and medical electronics. Her senior thesis was entitled “Heightened Effects of Thrombolytic Ac- This page was researched by Em- tions Due to Ultrasound.” Takeuchi worked as a licensed pharmacist at ily Fox, Nadia Makousky, Amanda Polvi, and Taylor Sorensen for Keio Hospital after graduating. -

Exploring the Magical Girl Transformation Sequence with Flash Animation

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design 5-10-2014 Releasing The Power Within: Exploring The Magical Girl Transformation Sequence With Flash Animation Danielle Z. Yarbrough Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Yarbrough, Danielle Z., "Releasing The Power Within: Exploring The Magical Girl Transformation Sequence With Flash Animation." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELEASING THE POWER WITHIN: EXPLORING THE MAGICAL GIRL TRANSFORMATION SEQUENCE WITH FLASH ANIMATION by DANIELLE Z. YARBROUGH Under the Direction of Dr. Melanie Davenport ABSTRACT This studio-based thesis explores the universal theme of transformation within the Magical Girl genre of Animation. My research incorporates the viewing and analysis of Japanese animations and discusses the symbolism behind transformation sequences. In addition, this study discusses how this theme can be created using Flash software for animation and discusses its value as a teaching resource in the art classroom. INDEX WORDS: Adobe Flash, Tradigital Animation, Thematic Instruction, Magical Girl Genre, Transformation Sequence RELEASING THE POWER WITHIN: EXPLORING THE MAGICAL GIRL TRANSFORMATION SEQUENCE WITH FLASH ANIMATION by DANIELLE Z. YARBROUGH A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art Education In the College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University 2014 Copyright by Danielle Z. -

![[Company Name]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0400/company-name-960400.webp)

[Company Name]

Banpresto Collector Items Product Catalog February 2015 Product Catalog February 2015 1. Purchase Orders are due October 8, 2014 2. Product will be shipped February 1, 2015 • There will be no opportunity for reorders. All orders are one and done. • Orders must be placed in case pack increments. • Every month Bandai will introduce a new line of products. For example, next month’s catalog will feature items available March 2015. Product Image Distribution Guidelines You may begin selling to your direct accounts and consumers immediately. Images are available upon request. • This 6.3” figure of Sailor Moon (Rei Hino in Japan) is part of the “Girls Memory” series of th 6.3” figures celebrating the 20 anniversary of Sailor Moon! • Collect and display with Sailor Moon & Sailor Mercury!! (Launch in January 2015) • Base included “Sailor Moon Crystal” airs on neoalley.com every 1st & 3rd Saturday of the month, the same time as Japan! ©Naoko Takeuchi / PNP, TOEI ANIMATION Product Ord # #31626 Name “Girls Memory” Figure Series – SAILOR MARS Assortment Info Age Grade 8+ Item # Item UPC Item Description Unit / Case Cost $16.00 31627 0-45557-31627-3 SAILOR MARS 32 SRP $28.00 Packaging Master Carton H W D H W D ITF-14 7.1 4.7 3.5 18.7 27.0 13.4 0-0045557-31626-6 Type Closed Box Weight 18.9 Total Case Pack 32 2” “Sailor Moon Crystal” airs on neoalley.com every 1st & 3rd Saturday of the month, the same time as Japan! ©Naoko Takeuchi / PNP, TOEI ANIMATION Product Ord # #31628 Name SAILOR MOON Collectable Figure for Girls Vol. -

Desenhos Animados: Questões De Ética E Comportamento Animal

Universidade Federal Fluminense Pós - graduação em Bioética, Ética Aplicada e Saúde Coletiva Associação ampla - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Universidade Federal Fluminense Juliana Clemente Machado O GATO DOMÉSTICO NOS DESENHOS ANIMADOS: QUESTÕES DE ÉTICA E COMPORTAMENTO ANIMAL Niterói 2015 Juliana Clemente Machado O gato doméstico nos desenhos animados: questões de ética e comportamento animal Tese apresentada Programa de Pós-Graduação em Bioética, Ética Aplicada e Saúde Coletiva, da Universidade Federal Fluminense como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Doutora. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Rita Leal Paixão Niterói 2015 M149 Machado, Juliana Clemente O gato doméstico nos desenhos animados: questões de ética e comportamento animal / Juliana Clemente Machado.- Niterói, 2015. 182 f. Orientador: Rita Leal Paixão Tese (Doutorado em Bioética, Ética Aplicada e Saúde Coletiva)– Universidade Federal Fluminense, Faculdade de Medicina, 2015. 1. Bioética. 2. Gatos. 3. Desenhos animados. 4. Mídia audiovisual. I. Titulo. CDD 174.90616 Juliana Clemente Machado O gato doméstico nos desenhos animados: questões de ética e comportamento animal Tese apresentada Programa de Pós-Graduação em Bioética, Ética Aplicada e Saúde Coletiva, da Universidade Federal Fluminense como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Doutora. BANCA EXAMINADORA Profª. Drª. Rita Leal Paixão (Orientadora) Universidade Federal Fluminense Prof. Dr. José Mario D’Almeida Universidade Federal Fluminense Prof. Dr. Daniel Braga Lourenço Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Profª. Drª Andrea Barbosa Osorio Sarandy Universidade Federal Fluminense Prof. Dr. Ricardo Tadeu Santori Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a Deus, por estar sempre comigo me ajudando a ser forte e otimista. -

Sailor Moon" : Género E Inclusión En Un Producto Cultural Japonés

This is the published version of the bachelor thesis: Albaladejo Pérez, Marina; Lozano Mendez, Artur, dir. Feminismo y LGTB+ en "Sailor Moon" : género e inclusión en un producto cultural japonés. 2019. (0 Estudis d’Àsia Oriental) This version is available at https://ddd.uab.cat/record/213039 under the terms of the license FACULTAD DE TRADUCCIÓN E INTERPRETACIÓN ESTUDIOS DE ASIA ORIENTAL TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO Curso 2018-2019 Feminismo y LGTB+ en Sailor Moon Género e inclusión en un producto cultural japonés Marina Albaladejo Pérez 1388883 TUTOR ARTUR LOZANO MÉNDEZ Barcelona, 3 de junio de 2019 Página de créditos Datos del Trabajo Título: CAST. Feminismo y LGTB+ en Sailor Moon: género e inclusión en un producto cultural japonés CAT. Feminisme i LGTB+ a Sailor Moon: gènere i inclusió en un producte cultural japonès ENG. Feminism and LGTB+ in Sailor Moon: gender and inclusion in a Japanese cultural product Autora: Marina Albaladejo Pérez Tutor: Artur Lozano Méndez Centro: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Estudios: Estudios de Asia Oriental (japonés) Curso académico: 2018/2019 Palabras clave CAST. Sailor Moon. Naoko Takeuchi. Feminismo. LGTB+. Inclusión. Feminidad. Masculinidad. Identidad de género. Vestimenta. Uniforme colegiala. Transgresión. CAT. Sailor Moon. Naoko Takeuchi. Feminisme. LGTB+. Inclusió. Feminitat. Masculinitat. Identitat de gènere. Vestimenta. Uniforme de col·legiala. Transgressió. ENG. Sailor Moon. Naoko Takeuchi. Feminism. LGBT+. Inclusion. Femininity. Masculinity. Gender identity. Clothing. School uniform. Transgression. Resum del TFG CAST. El presente trabajo ofrece un análisis de género e inclusión de la obra Bishōjo Senshi Sailor Moon (美少女戦士 セーラームーン) de Takeuchi Naoko. Se estudia este producto cultural japonés desde una perspectiva feminista, partiendo de la hipótesis que la obra fue subversiva dentro del mundo del manga, anime, y del género mahō shōjo del shōjo manga, al introducir la presencia de elementos feministas, personajes del colectivo LGTB+ y una diversidad amorosa y familiar que se distancia de los patrones hegemónicos. -

Sakura-Con 2017

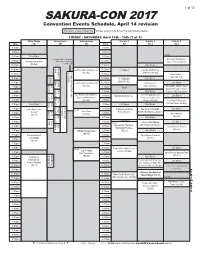

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2017 Convention Events Schedule, April 14 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 14th - 15th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 14th - 15th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 14th - 15th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Panels 9 Workshop Arts & Crafts Model Karaoke Console Gaming Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 Theater 4 Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Mahjong Miniatures Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB Skagit 2 Skagit 3 Time Time Chelan 4 Chelan 2 Building: 214 307-308 606-609 Time 616-617 618-619 615 620 Theater: 6A Center: 305 310 Theater: 309 Time Gaming: 614 613 Gaming: 612 Time 7:00am 7:00am 7:00am 7:00am 7:00am 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 14th - 15th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Mask Making 8:00am Irie, Mignogna, Glass, Crunchyroll Theater Block: Shiki Douji showcase: Someday’s Dreamers II: 8:00am 8:00am (8:45) Workshop Sabat showcase: 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am elDLIVE 1-4 Full Metal Panic! Sora 1-41-6 8:30am 8:30am (SC-ALL) Fullmetal Alchemist: (SC-13, sub) 1-8 (SC-10, sub) Let's Play Meetup (SC-13) Brotherhood 1-81-4 Relic Knights 2.0 Anki Overdrive & Miniatures Freeplay 9:00am 9:00am Setup 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am Open Karaoke 9:00am (SC-13, dub) AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am (SC-13, dub) (9:45) (9:45) (SC-ALL) 9:30am Doors -

Translation Studies: Shifts in Domestication and Foreignisation in Translating Japanese Manga and Anime (Part Four)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE 鹿児島純心女子短期大学研究紀要 第50号,87-97 2020Shifts in Domestication and Foreignisation in Translating Japanese Manga and Anime (Part Four) Translation Studies: Shifts in Domestication and Foreignisation in Translating Japanese Manga and Anime (Part Four) Matthew Watson Abstract: Like manga, there are anime series covering just about anything you can imagine, and after humble beginnings outside of Japan, it is now a booming international industry that rakes in billions of dollars each year. The way anime has been viewed and translated has changed dramatically over the last few decades. Key Words栀[Anime][Censorship][Fan-subs] (Received September 24, 2019) Anime This chapter will seek to examine anime and how it is translated and localised into English. It will look at the evolution and translation techniques of fansubs and their sometimes extreme levels of foreignisation. Then examine official licensed translation, looking at the Subs vs. Dubs debate, the heavy domestication and editing of anime and how the opinions of fans, the changing marketplace and the effect of fansubs have all forced companies to rethink the way they translate. Beginnings Japanese anime started in the early 20th century, where the so called‘3 fathers of anime’ Ōten Shimokawa, Junichi Kōuchi and Seitaro Kitayama began to adapt and experiment with the animation techniques from the West1. Anime continued to evolve through the 1920s and 30s and was actively used during WW2 by the Japanese imperial government and military to produce propaganda films. However, it was the post-war period where the modern idea of anime really began to take shape.