Massimiliano Trentin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 548.22 Kb

NEPAL’S NEW ALLIANCE: THE MAINSTREAM PARTIES AND THE MAOISTS Asia Report N°106 – 28 November 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. THE PARTIES................................................................................................................ 3 A. OUTLOOK .............................................................................................................................3 B. IMPERATIVES ........................................................................................................................4 C. INTERNAL TENSIONS AND CONSTRAINTS ..............................................................................5 D. PREPARATION FOR TALKS .....................................................................................................7 III. THE MAOISTS .............................................................................................................. 8 A. OUTLOOK .............................................................................................................................8 B. IMPERATIVES ........................................................................................................................9 C. INTERNAL TENSIONS AND CONSTRAINTS ............................................................................10 D. PREPARATION FOR TALKS -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

The Communist Party Sweden

INTERNATIONAL GUESTS GREETING MESSAGES 18 TH CONGRESS OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY SWEDEN Guests and Greetings from Costa Rica, Cuba, Czech Republik, Denmark, El Salvador, France, Guatemala, Honduras, DPR Korea, Lao PDR, Norway, Palestine, Philippines, Poland, Schwitzerland, Spain, Sri Lanka, Syria, US, Venezuela, Vietnam and WFTU All international guests were welcome on stage at the first day of the congress. International guests and greeting messages The Communist Party, Sweden, has friends Cuba: Embassy of Cuba all over the world. It was clearly visible on Denmark : Danish Communist Party at the 18 th congress 5-7 th of January 2017 El Salvador : Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) with many international guests present and France : Pole of Communist Revival in France, many greeting messages sent to the con - PRCF gress. DPR Korea: Embassy of DPR Korea 13 international delegations attended the congress in Laos : Embassy of Lao PDR Göteborg. They were representing organizations in Palestine : Popular Front for the Liberation of twelve countries in Europe, Middle East, Asia and Palestine (PFLP) South and Central America. Philippines : National Democratic Front (NDF) Among the guests were Communists, anti-imperi - Sri Lanka : People's Liberation Front (JVP) alists and other forces that play a progressive role in Syria: Syrian Communist Party (United) their countries. Like British Trade Unionists Against UK : Trade Unionists Against the EU the EU which for decades has worked for Britain to Venezuela: Embassy of Bolivarian republic of leave the EU and in the referendum in June last year Venezuelan was on the winning side. In addition to organizations that the guests represent, The following international guests were present in the Communist Party received greetings from seve - the congress premises in Göteborg: ral organizations from all over the world. -

From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund

7/2019 From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS | UI.SE Abstract The Russian-Syrian relationship turns 75 in 2019. The Soviet Union had already emerged as Syria’s main military backer in the 1950s, well before the Baath Party coup of 1963, and it maintained a close if sometimes tense partnership with President Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000). However, ties loosened fast once the Cold War ended. It was only when both Moscow and Damascus separately began to drift back into conflict with the United States in the mid-00s that the relationship was revived. Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Russia has stood by Bashar al-Assad’s embattled regime against a host of foreign and domestic enemies, most notably through its aerial intervention of 2015. Buoyed by Russian and Iranian support, the Syrian president and his supporters now control most of the population and all the major cities, although the government struggles to keep afloat economically. About one-third of the country remains under the control of Turkish-backed Sunni factions or US-backed Kurds, but deals imposed by external actors, chief among them Russia, prevent either side from moving against the other. Unless or until the foreign actors pull out, Syria is likely to remain as a half-active, half-frozen conflict, with Russia operating as the chief arbiter of its internal tensions – or trying to. This report is a companion piece to UI Paper 2/2019, Russia in the Middle East, which looks at Russia’s involvement with the Middle East more generally and discusses the regional impact of the Syria intervention.1 The present paper seeks to focus on the Russian-Syrian relationship itself through a largely chronological description of its evolution up to the present day, with additional thematically organised material on Russia’s current role in Syria. -

Read the Full PDF

en Books published to date in the continuing series o .:: -m -I J> SOVIET ADVANCES IN THE MIDDLE EAST, George Lenczowski, 1971. 176 C pages, $4.00 ;; Explores and analyzes recent Soviet policies in the Middle East in terms of their historical background, ideological foundations and pragmatic application in the 2 political, economic and military sectors. n PRIVATE ENTERPRISE AND SOCIALISM IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Howard S. Ellis, m 1970. 123 pages, $3.00 en Summarizes recent economic developments in the Middle East. Discusses the 2- significance of Soviet economic relations with countries in the area and suggests new approaches for American economic assistance. -I :::I: TRADE PATTERNS IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Lee E. Preston in association with m Karim A. Nashashibi, 1970. 93 pages, $3.00 3: Analyzes trade flows within the Middle East and between that area and other areas of the world. Describes special trade relationships between individual -C Middle Eastern countries and certain others, such as Lebanon-France, U.S .S.R. C Egypt, and U.S.-Israel. r m THE DILEMMA OF ISRAEL, Harry B. Ellis, 1970. 107 pages, $3.00 m Traces the history of modern Israel. Analyzes Israel 's internal political, eco J> nomic, and social structure and its relationships with the Arabs, the United en Nations, and the United States. -I JERUSALEM: KEYSTONE OF AN ARAB-ISRAELI SETTLEMENT, Richard H. Pfaff, 1969. 54 pages, $2.00 Suggests and analyzes seven policy choices for the United States. Discusses the religious significance of Jerusalem to Christians, Jews, and Moslems, and points out the cultural gulf between the Arabs of the Old City and the Western r oriented Israelis of West Jerusalem. -

Nepal's Constitution (Ii): the Expanding

NEPAL’S CONSTITUTION (II): THE EXPANDING POLITICAL MATRIX Asia Report N°234 – 27 August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE REVOLUTIONARY SPLIT ................................................................................... 3 A. GROWING APART ......................................................................................................................... 5 B. THE END OF THE MAOIST ARMY .................................................................................................. 7 C. THE NEW MAOIST PARTY ............................................................................................................ 8 1. Short-term strategy ....................................................................................................................... 8 2. Organisation and strength .......................................................................................................... 10 3. The new party’s players ............................................................................................................. 11 D. REBUILDING THE ESTABLISHMENT PARTY ................................................................................. 12 1. Strategy and organisation .......................................................................................................... -

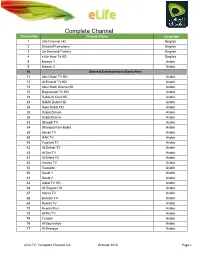

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

United Arab Republic 1 United Arab Republic

United Arab Republic 1 United Arab Republic ةدحتملا ةيبرعلا ةيروهمجلا Al-Gumhuriyah al-Arabiyah al-Muttahidah Al-Jumhuriyah al-Arabiyah al-MuttahidahUnited Arab Republic ← → 1958–1961 ← (1971) → ← → Flag Coat of arms Anthem Oh My Weapon[1] Capital Cairo Language(s) Arabic [2] Religion Secular (1958–1962) Islam (1962–1971) Government Confederation President - 1958–1970 Gamal Abdel Nasser United Arab Republic 2 Historical era Cold War - Established February 22, 1958 - Secession of Syria September 28, 1961 - Renamed to Egypt 1971 Area - 1961 1166049 km2 (450214 sq mi) Population - 1961 est. 32203000 Density 27.6 /km2 (71.5 /sq mi) Currency United Arab Republic pound Calling code +20 Al-Gumhuriyah al-Arabiyahةدحتملا ةيبرعلا ةيروهمجلا :The United Arab Republic (Arabic al-Muttahidah/Al-Jumhuriyah al-Arabiyah al-Muttahidah), often abbreviated as the U.A.R., was a sovereign union between Egypt and Syria. The union began in 1958 and existed until 1961, when Syria seceded from the union. Egypt continued to be known officially as the "United Arab Republic" until 1971. The President was Gamal Abdel Nasser. During most of its existence (1958–1961) it was a member of the United Arab States, a confederation with North Yemen. The UAR adopted a flag based on the Arab Liberation Flag of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, but with two stars to represent the two parts. This continues to be the flag of Syria. In 1963, Iraq adopted a flag that was similar but with three stars, representing the hope that Iraq would join the UAR. The current flags of Egypt, Sudan, and Yemen are also based on Arab Liberation Flag of horizontal red, white, and black bands. -

Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections 2008 Elections Parliamentary of Chronicle Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections Volume 42

Couverture_Ang:Mise en page 1 22.04.09 17:27 Page1 Print ISSN: 1994-0963 Electronic ISSN: 1994-098X INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CHRONICLE OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 2008 CHRONICLE OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS VOLUME 42 Published annually in English and French since 1967, the Chronicle of Parliamen tary Elections reports on all national legislative elections held throughout the world during a given year. It includes information on the electoral system, the background and outcome of each election as well as statistics on the results, distribution of votes and distribution of seats according to political group, sex and age. The information contained in the Chronicle can also be found in the IPU’s database on national parliaments, PARLINE. PARLINE is accessible on the IPU web site (http://www.ipu.org) and is continually updated. Inter-Parliamentary Union VOLUME 42 5, chemin du Pommier Case postale 330 CH-1218 Le Grand-Saconnex Geneva – Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 919 41 50 Fax: +41 22 919 41 60 2008 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.ipu.org 2008 Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections VOLUME 42 1 January - 31 December 2008 © Inter-Parliamentary Union 2009 Print ISSN: 1994-0963 Electronic ISSN: 1994-098X Photo credits Front cover: Photo AFP/Pascal Pavani Back cover: Photo AFP/Tugela Ridley Inter-Parliamentary Union Office of the Permanent Observer of 5, chemin du Pommier the IPU to the United Nations Case postale 330 220 East 42nd Street CH-1218 Le Grand-Saconnex Suite 3002 Geneva — Switzerland New York, N.Y. 10017 USA Tel.: + 41 22 919 -

MDE120602013 We Cannot Live Here Anymore, Refugees From

17 October 2013 Index: MDE 12/060/2013 ‘WE CANNOT LIVE HERE ANY MORE’ REFUGEES FROM SYRIA IN EGYPT “We don’t feel any more but we are alive, we live without hope as the days go past… All I want is to have my husband back. We want to be settled in any country where we can be safe… When we first came [to Egypt] everything was fine, but just before Eid [following Ramadan, in August], everything changed… We want a legal way to leave Egypt so that we don’t have to use the sea. We cannot live here any more.” A refugee whose husband was arrested from a boat trying to reach Italy and detained in the 2 nd Montaza police station in Alexandria. In the early hours of 17 September, a boat carrying at least 200 people left the Egyptian port city of Alexandria. It was heading to Italy when it was intercepted and pulled back to shore by the Egyptian Navy. Most of those on board the boat were refugees from Syria. When Amnesty International later interviewed some of the refugees, they described how, as they saw the Egyptian Navy ship approaching their boat, people started pleading with the Navy not to shoot, telling them that there were children on board. The Navy approached the boat and, according to witnesses, fired several shots into the hull of the boat. As far as Amnesty International is aware no shots were fired from the boat carrying the refugees. The incident resulted in the death of two people who were shot: Fadwa Taha , a 50-year-old Palestinian refugee woman from Syria, and Amr Dailool, a 30-year-old Syrian refugee. -

Nepal: Identity Politics and Federalism

NEPAL: IDENTITY POLITICS AND FEDERALISM Asia Report N°199 – 13 January 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. IDENTITY POLITICS IN NEPAL ................................................................................. 3 A. ETHNIC ACTIVISM: PAST AND PRESENT ....................................................................................... 3 1. Before 1990 .................................................................................................................................. 3 2. After 1990 .................................................................................................................................... 4 B. ETHNIC DEMANDS AND THE “PEOPLE’S WAR” ............................................................................. 5 C. FEDERALISM AFTER THE PEACE DEAL .......................................................................................... 7 III. THE POLITICS OF FEDERALISM .............................................................................. 9 A. THE MAOISTS .............................................................................................................................. 9 B. THE MAINSTREAM PARTIES ....................................................................................................... 10 1. The UML: if you can’t convince them, -

January 31, 1958 Report of the Hungarian Ambassador in Cairo on the Establishment of the United Arab Republic and the Syrian Public Opinion in 1958 (Exceprts)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified January 31, 1958 Report of the Hungarian Ambassador in Cairo on the establishment of the United Arab Republic and the Syrian public opinion in 1958 (exceprts) Citation: “Report of the Hungarian Ambassador in Cairo on the establishment of the United Arab Republic and the Syrian public opinion in 1958 (exceprts),” January 31, 1958, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, MOL-M-KS 288 f.32/1958. 8.ő.e. Translated by András Bocz. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122511 Summary: This report by the Hungarian ambassador in Cairo states that the Syrian people are wary toward President Nasser’s creation of the United Arab Republic, fearing he will enforce a dictatorship, however the Syrian communist party is in full support of the union. Original Language: Hungarian Contents: English Translation Strictly confidential! Reactions to and the aftermath of the events The events took the Syrian public totally unprepared. In the first few days the crowd, heated by nationalism, was cheering the idea of the union enthusiastically. However, it lasted only for a few days. Many of the people began to look at the likely political events from the point of view of their own personal fate. I tried to meet as many people I could and listen to many different views during these days. Low- and middle-ranking foreign affairs officials were extremely embittered, saying that that they would be the first to be dismissed. For example, the deputy head of the protocol department said that he would resign if he were to be transferred to Cairo.