Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers t was 1946 and film noir was everywhere, counter, The Jolson Story, Notorious, The and into the 70s and 80s, including King of from low budget quickies to major studio Spiral Stair-case, Anna and the King of Kings, El Cid, Sodom and Gomorrah, The Ireleases. Of course, the studios didn’t re - Siam , and more, so it’s no wonder that The V.I.P.s, The Power, The Private Life of Sher - alize they were making films noir, since that Strange Love of Martha Ivers got lost in the lock Holmes (for Wilder again), The Golden term had just been coined in 1946 by shuffle. It did manage to sneak in one Acad - Voyage of Sinbad, Providence, Fedora French film critic, Nino Frank. The noirs of emy Award nomination for John Patrick (Wilder again), Last Embrace, Time after 1946 included: The Killers, The Blue Dahlia, (Best Writing, Original Story), but he lost to Time, Eye of the Needle , Dead Men Don’t The Big Sleep, Gilda, The Postman Always Clemence Dane for Vacation from Marriage Wear Plaid and more. It’s one of the most Rings Twice, The Stranger, The Dark Mirror, (anyone heard of that one since?). impressive filmographies of any film com - The Black Angel , and The Strange Love of poser in history, and along the way he gar - Martha Ivers. When Martha Ivers, young, orphaned nered an additional six Oscar nominations heiress to a steel mill, is caught running and another two wins. The Strange Love of Martha Ivers was an away with her friend, she’s returned home “A” picture from Paramount, produced by to her aunt, whom she hates. -

Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood

Katherine Kinney Cold Wars: Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood n 1982 Louis Gossett, Jr was awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Gunnery Sergeant Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman, becoming theI first African American actor to win an Oscar since Sidney Poitier. In 1989, Denzel Washington became the second to win, again in a supporting role, for Glory. It is perhaps more than coincidental that both award winning roles were soldiers. At once assimilationist and militant, the black soldier apparently escapes the Hollywood history Donald Bogle has named, “Coons, Toms, Bucks, and Mammies” or the more recent litany of cops and criminals. From the liberal consensus of WWII, to the ideological ruptures of Vietnam, and the reconstruction of the image of the military in the Reagan-Bush era, the black soldier has assumed an increasingly prominent role, ironically maintaining Hollywood’s liberal credentials and its preeminence in producing a national mythos. This largely static evolution can be traced from landmark films of WWII and post-War liberal Hollywood: Bataan (1943) and Home of the Brave (1949), through the career of actor James Edwards in the 1950’s, and to the more politically contested Vietnam War films of the 1980’s. Since WWII, the black soldier has held a crucial, but little noted, position in the battles over Hollywood representations of African American men.1 The soldier’s role is conspicuous in the way it places African American men explicitly within a nationalist and a nationaliz- ing context: U.S. history and Hollywood’s narrative of assimilation, the combat film. -

December 2016 Calendar

December Calendar Exhibits In the Karen and Ed Adler Gallery 7 Wednesday 13 Tuesday 19 Monday 27 Tuesday TIMNA TARR. Contemporary quilting. A BOB DYLAN SOUNDSWAP. An eve- HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free AFTERNOON ON BROADWAY. Guys and “THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY” (2015- December 1 through January 2. ning of clips of Nobel laureate Bob blood pressure screening conducted Dolls (1950) remains one of the great- 108 min.). Writer/director Matt Brown Dylan. 7:30 p.m. by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. est musical comedies. Frank Loesser’s adapted Robert Kanigel’s book about music and lyrics find a perfect match pioneering Indian mathematician Registrations “THE DRIFTLESS AREA” (2015-96 min.). in Damon Runyon-esque characters Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel) and Bartender Pierre (Anton Yelchin) re- and a New York City that only exists in his friendship with his mentor, Profes- In progress turns to his hometown after his parents fantasy. Professor James Kolb discusses sor G.H. Hardy (Jeremy Irons). Stephen 8 Thursday die, and finds himself in a dangerous the show and plays such unforgettable Fry co-stars as Sir Francis Spring, and Resume Workshop................December 3 situation involving mysterious Stella songs as “A Bushel and a Peck,” “Luck Be Jeremy Northam portrays Bertrand DIRECTOR’S CUT. Film expert John Bos- Entrepreneurs Workshop...December 3 (Zoe Deschanel) and violent crimi- a Lady” and “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ Russell. 7:30 p.m. co will screen and discuss Woody Al- Financial Checklist.............December 12 nal Shane (John Hawkes). Directed by the Boat.” 3 p.m. -

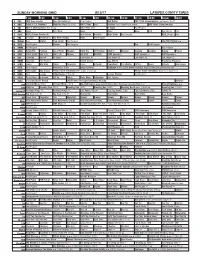

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

WEEK's MPLETE TELEVISION PROGRAMS N RTH JERSEY's ONLY WEEKLY Pictaria MAGAZINE

WEEK'S MPLETE TELEVISION PROGRAMS THE SUNDAY N RTH JERSEY'S ONLY WEEKLY PICTaRIA MAGAZINE i •on st Paterson Fair Lawn Garfield Ha;•don 1 Hawthorne Lodi , Little Falls Mou:dtain View NorEi Haledon Paterson Passaic Pompton Lakes Pro.specf Park Sincjac Tofowa Wuyne We•f Paterson DECEMBER 5, 1959 SANTA IN TOWN AGAIN VOL. XXXI, No. 4:8 .1, WHITE and SHAUGER, A Good Name to Remember for FURNITURE I! Living Room - Bed Room Dining Room RUGS AND' CARPETS A SPECIAL'n' Quality and Low Price 39 Years Serving the .Public 435 STRAIGI•T STI•ET (Corner 20th' Ave•) PA•I,I•ON, N.J. ß"The Place with the Clock" -- MUlberry 4-qSM Headqus,rters for En•ged Couples - L THE IDEAL PLACETO' DINE AND WINE . KITCHEH -•. • ß SEAFOOD BROILEDLOBSTER FROGS' I,EGS - DFT SHELL CRAB• - BLUEFISH - RAINBOW TROUT - HALIBUT- SALMON - SHRIMPS- SCALLOPS- YSTERS• CLAM - COD FISH - SWORDFISH - DAILYDINNERS/• TOP-HAT TALENT- Frankie Vaughan, British variety artist whose top hat and cane have become a familiar trade mark with --audiences here and abroad, will be a guest star on the NBC-TV I. PARRILLO - Network colorcast of the Dinah Shore program on Sunday, ...... Dec. 20. Vaughan is a top TV, recording, music hall and film --..:- favorite in England, and also has won applause for his American night club and TV performances. TheMan from'Equitable-asksii'. Youwant your child to ha've a better placein the sun, don't you? OFCOURSE YOU DO. But like someparents you •g- me,"there's still plenty oœ thne." Then, before you knowit, they'reall grownup and need your help to givethem that important start toward a proœession, L careeror business,or in settingup a home.Make surenow that your "helpinghand"' will be there whenit is needed.Equitable offers you a varietyoœ policiesfor youryoungster at low rates.For more information call.. -

Learning with Anne: Jason Nolan � 8/14/09 4:13 PM Deleted: Chapter Seven Early Childhood Education Looks at New Media for Young Girls

Learning with Anne: Jason Nolan ! 8/14/09 4:13 PM Deleted: Chapter Seven Early Childhood Education Looks at New Media for Young Girls Forthcoming in: Gammel, I. and Lefebvre, B. (Eds.) Anne of Green Gables: New Directions at 100. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Jason Nolan, PhD School of Early Childhood Education Ryerson University Here, too, the ethical responsibility of the school on the social side must be interpreted in the broadest and freest spirit; it is equivalent to that training of the child which will give him such possession of himself that he may take charge of himself; may not only adapt himself to the changes that are going on, but have power to shape and direct them. -- John Dewey1 In L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Avonlea (1909), sixteen-year-old Anne Shirley articulates a progressive pedagogical attitude that seems to coincide with Dewey’s Moral Principles in Education, published the same year: ‘No, if I can’t get along without whipping I shall not try to teach school. There are better ways of managing. I shall try to win my pupils’ affections and then they will want to do what I tell them.’2 Drawing from her own childhood experience depicted in Anne of Green Gables, fledgling teacher Anne describes a schooling experience that would treat the student as she once wished to be treated. As a child, Anne embodied the model of a self-directed learner who actively engaged with her physical and social environment, making meaning and constructing her own identity and understanding of the world, indeed creating a world in which she could live. -

Citizen Kane

A N I L L U M I N E D I L L U S I O N S E S S A Y B Y I A N C . B L O O M CC II TT II ZZ EE NN KK AA NN EE Directed by Orson Welles Produced by Orson Welles Distributed by RKO Radio Pictures Released in 1941 n any year, the film that wins the Academy Award for Best Picture reflects the Academy ' s I preferences for that year. Even if its members look back and suffer anxious regret at their choice of How Green Was My Valley , that doesn ' t mean they were wrong. They can ' t be wrong . It ' s not everyone else ' s opinion that matters, but the Academy ' s. Mulling over the movies of 1941, the Acade my rejected Citizen Kane . Perhaps they resented Orson Welles ' s arrogant ways and unprecedented creative power. Maybe they thought the film too experimental. Maybe the vote was split between Citizen Kane and The Maltese Falcon , both pioneering in their F ilm Noir flavor. Or they may not have seen the film at all since it was granted such limited release as a result of newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst ' s threats to RKO. Nobody knows, and it doesn ' t matter. Academy members can ' t be forced to vote for the film they like best. Their biases and political calculations can ' t be dissected. To subject the Academy to such scrutiny would be impossible and unfair. It ' s the Academy ' s awards, not ours. -

Snatcher Is Arrested Vittek Tosses Hat Into UAP Ring;

I ech : NEWSPAPER OF THE UNDERGRADUATES OF THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY I-I I VOL. LXXX No. 3 CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS, dI FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 19, 1960 5 Cents I- aivrse Snatcher A; Is Arrested Vittek Tosses Hat Into UAP Ring; 7 ByM [IT Poice Sergeant ID Soph, Junior, Senior Now Running -AL %--ll Last Monday evening shortly before least 75 counts of larceny, and then 7P.M., Sgt. James Olivieri and three he took us on a tour of the places in Soph Prexy Enters Race Wednesday XCambridge detectives, James Fitz- the Institute where he did his steal- igerald, William Meagher, and William ing" Jaffe's Platform Joe Vittek, President of the Class of 'G62, becamne the third person to an- 'Doucette, arrested 23-year-old James Admits To Twelve Thefts nounce his candidacy for the UAP. Entering the race last Wedn'esday, Vittek oArthur Joseph (alias James James) Olivieri said that Joseph's "mode of Presents Issues stated he had been urlged to do so by several campus leaders and had been think- ~on suspicion of stealing pocketbooks operation" was to go into a secretary's ing of the move for some time. from Vittek stated his v-iew-s MIT secretaries. office, ask the secretary to retrieve Ira Jaffe, '61, first to toss his hat in the following statement: "The position of UAP After his arrest Joseph admitted what his wife had left in the ladies' into the ring in the race for UAP, requires a person who has had much Tonmnitting 75 to 100 larcenies at room, and when she had gone, to gave The Tech the following state- experience in the processes and prob- IIT, Harvarld, BU, Simmons, Boston steal her money." According to the ment of his platforlm: lems of student government at MIIT. -

A Third Wave Feminist Re-Reading of Anne of Green Gables Maria Virokannas University of Tampere English

The Complex Anne-Grrrl: A Third Wave Feminist Re-reading of Anne of Green Gables Maria Virokannas University of Tampere English Philology School of Modern Languages and Translation Studies Tampereen yliopisto Englantilainen filologia Kieli- ja käännöstieteenlaitos Virokannas, Maria: The Complex Anne-Grrrl: A Third Wave Feminist Re-reading of Anne of Green Gables Pro gradu -tutkielma, 66 sivua + lähdeluettelo Syksy 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Tämän pro gradu -tutkielman tavoitteena oli selvittää voidaanko Lucy Maud Montgomeryn 1908 ilmestyneestä romaanista Anne of Green Gables löytää kolmannen aallon feminismin piirteitä. Erityisesti tutkin löytyykö romaanista piirteitä ristiriitaisuudesta ja sen omaksumisesta ja individualismin ideologiasta, feministisestä ja positiivisesta äitiydestä sekä konventionaalisen naisellisuuden etuoikeuttamisesta. Tutkielmani teoreettinen kehys muodostuu feministisestä kirjallisuuden tutkimuksesta, painottuen kolmannen aallon feministiseen teoriaan. Erityisesti feminististä äitiyttä tutkittaessa tutkielman kulmakivenä on Adrienne Richin teoria äitiydestä, jota Andrea O'Reilly on kehittänyt. Tämän teorian mukaan äitiys on toisaalta miesten määrittelemä ja kontrolloima, naista alistava instituutio patriarkaalisessa yhteiskunnassa, toisaalta naisten määrittelemä ja naiskeskeinen positiivinen elämys, joka potentiaalisesti voimauttaa naisia. Kolmannen aallon feminismi korostaa eroja naisten välillä ja naisissa itsessään, -

Official Announcement - January 26 - February 1 - 1941

Prairie View A&M University Digital Commons @PVAMU PV Week Academic Affairs Collections 1-26-1941 Official Announcement - January 26 - February 1 - 1941 Prairie View State College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-announcement Recommended Citation Prairie View State College, "Official Announcement - January 26 - February 1 - 1941" (1941). PV Week. 636. https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-announcement/636 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Affairs Collections at Digital Commons @PVAMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in PV Week by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @PVAMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ************************************************************* **************-<**¥*x***************************************** ******** PRAIRIE VIEW STATE COLLEGE ******** ******* ******* ****** "0L Q WEEKLY CALENDAR NO 17 ****** ******* ******* ******** January 26 - February 1, 1941 ******** ***********>.*-:<>,;****************************** **************** *************************** ************* *****************>.*** SUNDAY. JANUARY 26 9;00 A - Sunday School 11:00 A M - Morning Worship: PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY - College Chaplain 7:00 P M - Vesper - Faculty Debate - RESOLVED: THAT TEXAS SHOULD IN CREASE THE TAX ON NATURAL RESOURCES Affirmative Negative R W Hilliard J 0 Hopson H E Wright R A Smith Mrs M A Sanders Miss A L Sheffield Miss T. L Cunningham, Librarian Miss C Bradley, Librarian MONDAY. JANUARY 27 -

Exploring Movie Construction & Production

SUNY Geneseo KnightScholar Milne Open Textbooks Open Educational Resources 2017 Exploring Movie Construction & Production: What’s So Exciting about Movies? John Reich SUNY Genesee Community College Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Reich, John, "Exploring Movie Construction & Production: What’s So Exciting about Movies?" (2017). Milne Open Textbooks. 2. https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Milne Open Textbooks by an authorized administrator of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exploring Movie Construction and Production Exploring Movie Construction and Production What's so exciting about movies? John Reich Open SUNY Textbooks © 2017 John Reich ISBN: 978-1-942341-46-8 ebook This publication was made possible by a SUNY Innovative Instruction Technology Grant (IITG). IITG is a competitive grants program open to SUNY faculty and support staff across all disciplines. IITG encourages development of innovations that meet the Power of SUNY’s transformative vision. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks Milne Library State University of New York at Geneseo Geneseo, NY 14454 This book was produced using Pressbooks.com, and PDF rendering was done by PrinceXML. Exploring Movie Construction and Production by John Reich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Dedication For my wife, Suzie, for a lifetime of beautiful memories, each one a movie in itself. -

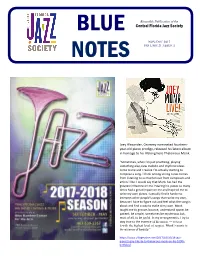

Nov/Dec 2017 Volume 21, Issue 5

Bimonthly Publication of the Central Florida Jazz Society BLUE NOV/DEC 2017 VOLUME 21, ISSUE 5 NOTES Joey Alexander, Grammy-nominated fourteen- year-old piano prodigy, released his latest album in homage to his lifelong hero Thelonious Monk. “Sometimes, when I’m just practicing, playing something else, new melodic and rhythmic ideas come to me and I realize I’m actually starting to compose a song. I think writing strong tunes comes from listening to so much music from composers and artists I like. I would say that Monk has had the greatest influence on me. Hearing his pieces so many times had a great impact on me and inspired me to write my own pieces. I actually find it harder to interpret other people’s songs than write my own, because I have to figure out and feel what the song is about and find a way to make it my own. Monk taught me to groove, bounce, understand space, be patient, be simple, sometimes be mysterious but, most of all, to be joyful. In my arrangements, I try to stay true to the essence of his music — to treat it with the highest level of respect. Monk’s music is the essence of beauty.” https://www.villagevoice.com/2017/10/10/18-jazz- pianists-pay-tribute-to-thelonious-monk-on-his-100th- birthday/ CFJS 3208 W. Lake Mary Blvd., Suite 1720 President’s Lake Mary, FL 32746-3467 [email protected] Improv http://centralfloridajazzsociety.com By Carla Page Executive Committee The very first thing I want to do is apologize for our last Blue Carla Page Notes.