Lowland Native Grasslands of Tasmania Ecological Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folklore & History of the Heritage Highway

Folklore & History of the Heritage Highway Keep an eye out between Tunbridge and Kemton for sixteen silhouettes. Some are quite close to road, some are high on the hilltops. What stories can they tell us about the history of this intriguing region. Page 2 Two hundred years on there’s still plenty of ways to get held up on the Heritage Highway The Silhouette sculpture trail along the Southern half of the Midland Highway is completed, nine years after it was started by locals Folko Kooper and Maureen Craig. The trail between Tunbridge and Kempton, has become an enjoyable feature of the journey along the highway. Installation of four coaching-related sculptures at Kempton earlier this year marked completion of a trail which now has 16 pieces. Page 3 Leaving Oatlands towards the North, on the right side of the Heritage Highway. Troop Of Soldiers—St Peters Pass Van Diemen’s Land was first and foremost a British military outpost. Soldiers accompanied the convicts on the transport ships, supervised the rationing of supplies, and guarded the chain gangs, They also supervised construction of bridges public and private buildings– as well as watching out for the French! Most didn’t stay long. There were other British interests around the world to defend. Many of the convicts they guarded had also been soldiers, but were reduced to committing crime once the wars they were fighting ended and they were out of a job. Chain Gang—North off York Plains Turn-off There was a lot to do to build the colony of Van Diemen’s Land. -

Tracing History

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911 Tracing History Phylogenetic, Taxonomic, and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family BY ANNIKA VINNERSTEN ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2003 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lindahlsalen, EBC, Uppsala, Friday, December 12, 2003 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Vinnersten, A. 2003. Tracing History. Phylogenetic, Taxonomic and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911. 33 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-5814-9 This thesis concerns the history and the intrafamilial delimitations of the plant family Colchicaceae. A phylogeny of 73 taxa representing all genera of Colchicaceae, except the monotypic Kuntheria, is presented. The molecular analysis based on three plastid regions—the rps16 intron, the atpB- rbcL intergenic spacer, and the trnL-F region—reveal the intrafamilial classification to be in need of revision. The two tribes Iphigenieae and Uvularieae are demonstrated to be paraphyletic. The well-known genus Colchicum is shown to be nested within Androcymbium, Onixotis constitutes a grade between Neodregea and Wurmbea, and Gloriosa is intermixed with species of Littonia. Two new tribes are described, Burchardieae and Tripladenieae, and the two tribes Colchiceae and Uvularieae are emended, leaving four tribes in the family. At generic level new combinations are made in Wurmbea and Gloriosa in order to render them monophyletic. The genus Androcymbium is paraphyletic in relation to Colchicum and the latter genus is therefore expanded. -

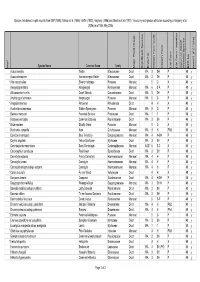

BFS048 Site Species List

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Welcome to the Southern Midlands

Welcome to the Southern Midlands SOUTHERN MIDLANDS COUNCIL Page 1 of 30 New Residents Information As Mayor of the Southern Midlands Council and on behalf of my fellow Councillors, I wish to extend a warm welcome and thank you for choosing to live in the Southern Midlands. Kind Regards Alex Green MAYOR SOUTHERN MIDLANDS COUNCIL Page 2 of 30 New Residents Information Contents About our Council ............................................................................................................. 4 Council Offices .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Municipal Map ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Councillors............................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Council Meetings ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Services ............................................................................................................................. 10 Development & Environmental Services ................................................................................................................... 10 Community & Corporate Development -

Exploring Our Frogs (Years 7–8)

Exploring our frogs (Years 7–8) Lesson plan Victorian Curriculum F–101 links: Introduction Science Investigating the frogs of your local area provides a great context for developing student Levels 7 and 8 understanding about biological classification, Science Understanding ecosystem processes and the impact that humans have on the natural environment. It is Science as a Human Endeavour also a great way to encourage students to Science and technology contribute to finding explore, develop their observational skills and to solutions to a range of contemporary issues; enjoy the natural world around them. these solutions may impact on other areas of society and involve ethical considerations These activities use digital applications such as (VCSSU090) Melbourne Water’s Frog Census and the Atlas Biological sciences of Living Australia (ALA) to develop students’ ICT skills. There are differences within and between groups of organisms; classification helps The Frog Census app is a powerful citizen organise this diversity (VCSSU091) science tool that enables students, their families and the wider community to improve our Interactions between organisms can be understanding of the biology and distribution of described in terms of food chains and food webs and can be affected by human activity frog species in Melbourne; information that will (VCSSU093) help to develop effective policy and management strategies to conserve and Digital technologies enhance these populations. Data and information Activity 1: Finding our frogs Analyse and visualise data using a range of software to create information, and use Students explore local frogs using the Atlas of structured data to model objects or events Living Australia and learn about how frogs are (VCDTDI038) named and classified by biologists. -

Act Native Woodland Conservation Strategy and Action Plans

ACT NATIVE WOODLAND CONSERVATION STRATEGY AND ACTION PLANS PART A 1 Produced by the Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development © Australian Capital Territory, Canberra 2019 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from: Director-General, Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate, ACT Government, GPO Box 158, Canberra ACT 2601. Telephone: 02 6207 1923 Website: www.planning.act.gov.au Acknowledgment to Country We wish to acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land we are meeting on, the Ngunnawal people. We wish to acknowledge and respect their continuing culture and the contribution they make to the life of this city and this region. Accessibility The ACT Government is committed to making its information, services, events and venues as accessible as possible. If you have difficulty reading a standard printed document and would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, such as large print, please phone Access Canberra on 13 22 81 or email the Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate at [email protected] If English is not your first language and you require a translating and interpreting service, please phone 13 14 50. If you are deaf, or have a speech or hearing impairment, and need the teletypewriter service, please phone 13 36 77 and ask for Access Canberra on 13 22 81. For speak and listen users, please phone 1300 555 727 and ask for Canberra Connect on 13 22 81. For more information on these services visit http://www.relayservice.com.au PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER CONTENTS VISION ........................................................................................................... -

Intravenous Alfaxalone Anaesthesia in Two Squamate Species: Eublepharis Macularius and Morelia Spilota Cheynei

INTRAVENOUS ALFAXALONE ANAESTHESIA IN TWO SQUAMATE SPECIES: EUBLEPHARIS MACULARIUS AND MORELIA SPILOTA CHEYNEI Tesi per il XXIX Ciclo del Dottorato in Scienze Veterinarie, Curriculum Scienze Cliniche Veterinarie Dipartimento di Scienze Veterinarie, Universita’ degli Studi di Messina Tutor: Prof. Filippo Spadola Cotutor: Prof. Zdenek Knotek Dr. Manuel Morici Sommario L’anestesia negli Squamati è una costante sfida della medicina e chirurgia dei rettili. Le differenze morfo-fisiologiche di questi taxa, rendono difficilmente applicabile i comuni concetti di anestesiologia veterinaria usati con successo negli altri animali da compagnia. Diversi protocolli anestetici sono stati utilizzati, sia per l’induzione che per il mantenimento, sia negli ofidi che nei sauri, ma con risultati variabili. Di fatti la maggior parte dei protocolli risultano in induzione o recuperi troppo brevi o troppo lunghi. L’obbiettivo di questa tesi dottorale è di valutare l’efficacia di un anestetico steroideo (alfaxalone), somministrato per via endovenosa in due specie di squamati usati come modello: il geco leopardo (Eublepharis macularius) e il pitone tappeto (Morelia spilota cheynei). Due metodi di somministrazione endovenosa (vena giugulare nei gechi e vena caudale nei serpenti) sono stati analizzati e descritti, usando un dosaggio di anestetico di 5 mg/kg in 20 gechi leopardo, e di 10 mg/kg in 10 pitoni tappeto. Nei gechi il tempo di induzione, il tempo di perdita del tono mandibolare, l’intervallo di anestesia chirurgica e il recupero completo sono stati rispettivamente di 27.5 ± 30.7 secondi, 1.3 ± 1.4 minuti, 12.5 ± 2.2 minuti and 18.8 ± 12.1 minuti. Nei pitoni tappeto, il tempo di induzione, la perdita di sensazione, il tempo di inserimento del tubo endotracheale, l’intervallo di anestesia chirurgica e il recupero sono stati rispettivamente di 3.1±0.8 minuti, 5.6±0.7 minuti, 6.9±0.9 minuti, 18.8±4.7 minuti, e 36.7±11.4 minuti. -

ACT, Australian Capital Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Frogs & Reptiles NE Vic 2018 Online

Reptiles and Frogs of North East Victoria An Identication and Conservation Guide Victorian Conservation Status (DELWP Advisory List) cr critically endangered en endangered Reptiles & Frogs vu vulnerable nt near threatened dd data deficient L Listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (FFG, 1988) Size: of North East Victoria Lizards, Dragons & Skinks: Snout-vent length (cm) Snakes, Goannas: Total length (cm) An Identification and Conservation Guide Lowland Copperhead Highland Copperhead Carpet Python Gray's Blind Snake Nobbi Dragon Bearded Dragon Ragged Snake-eyed Skink Large Striped Skink Frogs: Snout-vent length male - M (mm) Snout-vent length female - F (mm) Austrelaps superbus 170 (NC) Austrelaps ramsayi 115 (PR) Morelia spilota metcalfei – en L 240 (DM) Ramphotyphlops nigrescens 38 (PR) Diporiphora nobbi 8.4 (PR) Pogona barbata – vu 25 (DM) Cryptoblepharus pannosus Snout-Vent 3.5 (DM) Ctenotus robustus Snout-Vent 12 (DM) Guide to symbols Venomous Lifeform F Fossorial (burrows underground) T Terrestrial Reptiles & Frogs SA Semi Arboreal R Rock-dwelling Habitat Type Alpine Bog Montane Forests Alpine Grassland/Woodland Lowland Grassland/Woodland White-lipped Snake Tiger Snake Woodland Blind Snake Olive Legless Lizard Mountain Dragon Marbled Gecko Copper-tailed Skink Alpine She-oak Skink Drysdalia coronoides 40 (PR) Notechis scutatus 200 (NC) Ramphotyphlops proximus – nt 50 (DM) Delma inornata 13 (DM) Rankinia diemensis Snout-Vent 7.5 (NC) Christinus marmoratus Snout-Vent 7 (PR) Ctenotus taeniolatus Snout-Vent 8 (DM) Cyclodomorphus praealtus -

Chicago Academy of Sciences, Vol. 7, No. 2

BULLETIN OF THE CHICAGO ACADEMY OF SCIENCES A SYNOPSIS OF THE AMERICAN FORMS OF AGKISTRODON (COPPERHEADS AND MOCCASINS) BY HOWARD K. GLOYD Chicago Academy of Sciences AND ROGER CONANT Philadelphia Zoological Society CHICAGO Published by the Academy 1943 The Bulletin of the Chicago Academy of Sciences was initiated in 1883 and volumes 1 to 4 were published prior to June, 1913. During the following twenty-year period it was not issued. Volumes 1, 2, and 4 contain technical or semi-technical papers on various subjects in the natural sciences. Volume 3 contains museum reports, descriptions of museum exhibits, and announcements. Publication of the Bulletin was resumed in 1934 with volume 5 in the present format. It is now regarded as an outlet for short to moderate-sized original papers on natural history, in its broad sense, by members of the museum staff, members of the Academy, and for papers by other authors which are based in considerable part upon the collections of the Academy. It is edited by the Director of the Museum with the assistance of a committee from the Board of Scientific. Governors.. The separate numbers are issued at irregular intervals and distributed to libraries and scientific organizations, and to specialists with whom the Academy maintains exchanges. A reserve is set aside for future need as exchanges and the remainder of the edition offered for sale at a nominal price. When a suffi- cient number of pages have been printed to form a volume of convenient size, a title page, table of contents, and index are supplied to libraries and institutions which receive the entire series. -

From Mainland Southeastern Australia, with Ar

© The Authors, 2018. Journal compilation © Australian Museum, Sydney, 2018 Records of the Australian Museum (2018) Vol. 70, issue number 5, pp. 423–433. ISSN 0067-1975 (print), ISSN 2201-4349 (online) https://doi.org/10.3853/j.2201-4349.70.2018.1715 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:62503ED7-0C67-4484-BCE7-E4D81E54A41B Michael F. Braby orcid.org/0000-0002-5438-587X A new subspecies of Neolucia hobartensis (Miskin, 1890) (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) from Mainland Southeastern Australia, with a Review of Butterfly Endemism in Montane Areas in this Region Michael F. Braby1* and Graham E. Wurtz2 1 Division of Ecology and Evolution, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Acton ACT 2601, Australia, and National Research Collections Australia, Australian National Insect Collection, GPO Box 1700, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 2 Thurgoona NSW 2640, Australia [email protected] Abstract. Neolucia hobartensis albolineata ssp. nov. is illustrated, diagnosed, described and compared with the nominate subspecies N. hobartensis hobartensis (Miskin, 1890) from Tasmania and N. hobartensis monticola Waterhouse & Lyell, 1914 from northern New South Wales, Australia. The new subspecies is restricted to montane areas (mainly >1000 m) in subalpine and alpine habitats on the mainland in southeastern Australia (southern NSW, ACT, VIC) where its larvae specialize on Epacris spp. (Ericaceae). It thus belongs to a distinct set of 22 butterfly taxa that are endemic and narrowly restricted to montane areas (>600 m, but mainly >900 m) on the tablelands and plateaus of mainland southeastern Australia. Monitoring of these taxa, including N. hobartensis ssp., is urgently required to assess the extent to which global climate change, particularly temperature rise and large-scale fire regimes, are key threatening processes. -

Edible Native Plants Cheeseberry Leptecophylla Juniperina Coast Beardheath Or Native Currant Coast Daisybush Olearia Axillaris Coastal Wattle Acacia Longifolia Subsp

Copperleaf Snowberry Gaultheria hispida Ants Delight Acrotriche serrulata Barilla or Grey Saltbush Atriplex cinerea Bidgee-widgee Acaena novae-zelandiae Bower Spinach Tetragonia implexicoma Cape Barren Tea Correa alba Copperleaf Snowberry Gaultheria hispida Running Postman Kennedia prostrata Woolly Teatree Leptospermum lanigerum Edible Native Plants Cheeseberry Leptecophylla juniperina Coast Beardheath or Native Currant Coast Daisybush Olearia axillaris Coastal Wattle Acacia longifolia subsp. sophorae Cranberry Heath Astroloma humifusum OF TASMANIA subsp. juniperina Yellow Everlastingbush Ozothamnus obcordatus Key PART OF PLANT USED Underground Leaves/Leaf Bases Flowers Fruit Part Creeping Strawberry Pine Cutting Grass Gahnia grandis Erect Currantbush Leptomeria drupacea Grasstree, yamina or Green Appleberry Billardiera mutabilis Microcachrys tetragona Geebung Persoonia spp. Yacca Xanthorrhoea australis Purple Appleberry Meristem/Bud Exudate/Sap Seeds PREPARATION AND USE Snack Process Cook Eat Raw Tea Sweet Drink Flavouring CAUTION Hazard / Toxin Harvest Kills Plant Heartberry Aristotelia peduncularis Kangaroo Apple Solanum laciniatum Leeklily Bulbine spp. Lemon-leaf Heathmyrtle Baeckea gunniana Macquarie Vine or Blue Flaxlily Dionella spp. River Mint Mentha australis Native Grape Muehlenbeckia spp. Manfern or lakri Dicksonia antarctica or Milkmaids Burchardia umbellata Mountain Pepper Tasmannia lanceolata Native Cherry Exocarpus cupressiformis Native Ivyleaf Violet Viola hederacea Native Raspberry Rubus pavifolius Cyathea ssp. Native Bluebell Wahlenbergia spp. More information Cautionary Notes This poster is only a guide to what’s potentially edible. - sance so be cautious. Consume any new or unfamiliar food in small quantities. Ensure fruits are fully ripe. Note it’s often best not to ingest seeds or pips. cultivation and contemporary use of our edible native plants is still an evolving art and science. Source plants for your garden from native plant nurseries.