Salazar David 2017 Masterinfi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Angel of Ferrara

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Goldsmiths Research Online The Angel of Ferrara Benjamin Woolley Goldsmith’s College, University of London Submitted for the degree of PhD I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own Benjamin Woolley Date: 1st October, 2014 Abstract This thesis comprises two parts: an extract of The Angel of Ferrara, a historical novel, and a critical component entitled What is history doing in Fiction? The novel is set in Ferrara in February, 1579, an Italian city at the height of its powers but deep in debt. Amid the aristocratic pomp and popular festivities surrounding the duke’s wedding to his third wife, the secret child of the city’s most celebrated singer goes missing. A street-smart debt collector and lovelorn bureaucrat are drawn into her increasingly desperate attempts to find her son, their efforts uncovering the brutal instruments of ostentation and domination that gave rise to what we now know as the Renaissance. In the critical component, I draw on the experience of writing The Angel of Ferrara and nonfiction works to explore the relationship between history and fiction. Beginning with a survey of the development of historical fiction since the inception of the genre’s modern form with the Walter Scott’s Waverley, I analyse the various paratextual interventions—prefaces, authors’ notes, acknowledgements—authors have used to explore and explain the use of factual research in their works. I draw on this to reflect in more detail at how research shaped the writing of the Angel of Ferrara and other recent historical novels, in particular Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. -

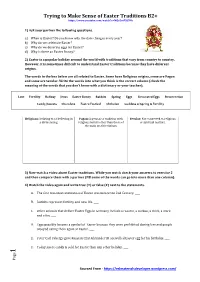

Trying to Make Sense of Easter Traditions B2+

Trying to Make Sense of Easter Traditions B2+ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQz2mF3jDMc 1) Ask your partner the following questions. a) When is Easter? Do you know why the date changes every year? b) Why do we celebrate Easter? c) Why do we decorate eggs for Easter? d) Why is there an Easter Bunny? 2) Easter is a popular holiday around the world with traditions that vary from country to country. However, it is sometimes difficult to understand Easter traditions because they have different origins. The words in the box below are all related to Easter. Some have Religious origins, some are Pagan and some are Secular. Write the words into what you think is the correct column (check the meaning of the words that you don’t know with a dictionary or your teacher). Lent Fertility Holiday Jesus Easter Bunny Rabbits Spring Eggs Decorated Eggs Resurrection Candy/Sweets Chocolate Eostre Festival Christian Goddess of Spring & Fertility Religious: Relating to or believing in Pagan: A person or tradition with Secular: Not connected to religious a divine being. religious beliefs other than those of or spiritual matters. the main world religions. 3) Now watch a video about Easter traditions. While you watch check your answers to exercise 2 and then compare them with a partner (NB some of the words can go into more than one column). 4) Watch the video again and write true (T) or false (F) next to the statements. A. The first recorded celebration of Easter was before the 2nd Century. ____ B. Rabbits represent fertility and new life. -

Wednesday Reflection: Rabbits

Wednesday Reflection: Rabbits Over the past few weeks I have been reflecting on visitors to the manse garden, including hedgehogs, butterflies, bats and fairies. Towards evening, we are blessed with an occasional visit from rabbits. Quietly, they sneak under the fence and stand motionless, poised in the middle of the lawn. The moment the spot me watching them they dart out of sight with immense speed. What might we say of rabbits in the Christian tradition? Dating from the Mediaeval period, many churches have rabbits carved into the stonework. Rabbits and hares were often depicted interchangeably. Three hares sharing ears between them artistically represent the Holy Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. There is an excellent example of this in Paderborn Cathedral in Germany. In his painting Agony in the Garden, the Italian artist, Andrea Mantegna, portrays the suffering of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. The disciples lie asleep while Christ prays on an elevated rock. The imposing walls of the city of Jerusalem can be seen in the background. Under the night sky, three rabbits conspicuously sit on the path which meanders through the garden. A symbol of the Trinity, one of the rabbits makes its way to be with Jesus; this is the Second Person of the Trinity. Elsewhere in Christianity, rabbits are a symbol of sin. In Wimborne Minster in Dorset, there are two ornate stone corbels. In the first, a rabbit is in the mouth of a hound and, in the second, a rabbit is being hunted by a hawk. In both cases, these images represent Christ hunting sin. -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

The Evolution of Landscape in Venetian Painting, 1475-1525

THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 by James Reynolds Jewitt BA in Art History, Hartwick College, 2006 BA in English, Hartwick College, 2006 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by James Reynolds Jewitt It was defended on April 7, 2014 and approved by C. Drew Armstrong, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture Kirk Savage, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Ann Sutherland Harris, Professor Emerita, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by James Reynolds Jewitt 2014 iii THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 James R. Jewitt, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 Landscape painting assumed a new prominence in Venetian painting between the late fifteenth to early sixteenth century: this study aims to understand why and how this happened. It begins by redefining the conception of landscape in Renaissance Italy and then examines several ambitious easel paintings produced by major Venetian painters, beginning with Giovanni Bellini’s (c.1431- 36-1516) St. Francis in the Desert (c.1475), that give landscape a far more significant role than previously seen in comparable commissions by their peers, or even in their own work. After an introductory chapter reconsidering all previous hypotheses regarding Venetian painters’ reputations as accomplished landscape painters, it is divided into four chronologically arranged case study chapters. -

Integration of Visual Art for Small Worshipping Communities

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theology Conference Papers School of Theology 2011 Integration of Visual Art for Small Worshipping Communities Angela M. McCarthy University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_conference Part of the Religion Commons This conference paper was originally published as: McCarthy, A. M. (2011). Integration of Visual Art for Small Worshipping Communities. Worship in Small Congregations. This conference paper is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_conference/9. For more information, please contact [email protected]. National Conference January 2011 Abstract Integration of visual art for small worshipping communities A difficulty for small worshipping communities is having the resources and personnel to provide suitable enervating opportunities for reflection on the Word during worship that enriches and enlivens their community action. Research has shown that interaction with visual imagery assists contemplation and integration of text and will therefore assist those gathered to consider the Scripture of the day. Visual imagery in art has been neglected as a source of theology and hence the vocabulary needed to ‘read’ the artworks relevant to Scripture will have to be re-learnt. This paper will provide an understanding of how visual arts can augment Scriptural understanding and the interaction within a small community. A list of symbols, attributes and emblems will be provided with visual examples so that this technique can be explored. Images are readily available through online sources and this augments the capacity of the small worshipping community to develop their resources. -

Pellucid Paper by Adam Wickberg

PELLUCID PAPER BY ADAM WICKBERG Pellucid Paper Bureaucratic Media And Poetry In Early Modern Spain Technographies Series Editors: Steven Connor, David Trotter and James Purdon How was it that technology and writing came to inform each other so exten- sively that today there is only information? Technographies seeks to answer that question by putting the emphasis on writing as an answer to the large question of ‘through what?’. Writing about technographies in history, our con- tributors will themselves write technographically. Pellucid Paper Bureaucratic Media And Poetry In Early Modern Spain Adam Wickberg OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS London 2018 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2018 Copyright © 2018 Adam Wickberg This is an open access book, licensed under Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy their work so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or simi- lar license. No permission is required from the authors or the publisher. Statutory fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Read more about the license at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 Freely available at: http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/pellucid-paper/ Cover Art, figures, and other media included with this book may be under different copyright restrictions. Cover Illustration © 2018 Navine G. Khan-Dossos Print ISBN 978-1-78542-054-2 PDF ISBN 978-1-78542-055-9 OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS Open Humanities Press is an international, scholar-led open access publishing collective whose mission is to make leading works of contemporary critical thought freely available worldwide. -

Peter Bruegel the Elder

PETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER Pieter Bruegel the Elder 1525–1530) was the most significant artist of Dutch and Flemish Renaiss- ance painting, a painter and printmaker, known for his landscapes and peasant scenes; he was a pioneer in making both types of subject the focus in large paintings. He was a formative influence on Dutch Golden Age painting and later painting in general in his innovative choices of subject matter, as one of the first generation of artists to grow up when religious subjects had ceased to be the natural subject matter of painting. He also painted no portraits, the other mainstay of Netherlandish art. After his training and travels to Italy, he returned in 1555 to settle in Antwerp, where he worked mainly as a prolific designer of prints for the leading publisher of the day. Only towards the end of the decade did he switch to make painting his main medium, and all his famous paintings come from the following period of little more than a decade before his early death, when he was probably in his early forties, and at the height of his powers. As well as looking forwards, his art reinvigorates medieval subjects such as marginal drolleries of ordinary life in illuminated manu- scripts, and the calendar scenes of agricultural labours set in land- scape backgrounds, and puts these on a much larger scale than before, and in the expensive medium of oil painting. He does the same with the fantastic and anarchic world developed in Renaissance prints and book illustrations. Pieter Bruegel specialized in genre paintings populated by peasants, often with a landscape element, though he also painted religious works. -

Pastor's Meanderings 4 – 5 May 2019 Third Sunday Of

PASTOR’S MEANDERINGS 4 – 5 MAY 2019 THIRD SUNDAY OF EASTER (C) SUNDAY REFLECTION Just as the risen Jesus prepared a meal for His disciples on the shore of the Lake of Tiberias, so He feeds us in a special way, in Word and in Sacrament in this Mass. We are the members of His family, we share His interests and, above all, His mission to show God’s love for all men and women throughout the world. STEWARDSHIP: In today’s Gospel, Jesus tells Peter again and again, “If you love Me, feed My sheep.” He says the same to each of us, “If you love Me, use the gifts I have given you to serve your brothers and sisters.” Nicholas Murray Butler “I divide the world in three classes: The few who make things happen, the many who watch things happen, the overwhelming majority who have no notion of what happens.” READINGS FOR THE FOURTH SUNDAY OF EASTER 11 MAY ‘19 Acts 13:14, 43-52: We hear today about the missionary activity of Paul and Barnabas, as the Gospel spreads beyond Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Rev. 7:9, 14-17: John gives an account of his vision of the vast crowd worshipping in the court of heaven. Jn. 10:27-30: Jesus, the Model Shepherd, gives eternal life to His disciples, the members of His flock. St. Augustine of Hippo “Christ is not valued at all unless He be valued above all.” EASTER SYMBOLS LILIES: There are a number of legends surrounding the plant that we refer to as the Easter Lily. -

Bartolomeo Maranta's 'Discourse' on Titian's Annunciation in Naples: Introduction1

Bartolomeo Maranta’s ‘Discourse’ on Titian’s Annunciation in Naples: introduction1 Luba Freedman Figure 1 Titian, The Annunciation, c. 1562. Oil on canvas, 280 x 193.5 cm. Naples: Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte (on temporary loan). Scala/Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali/Art Resource. Overview The ‘Discourse’ on Titian’s Annunciation is the first known text of considerable length whose subject is a painting by a then-living artist.2 The only manuscript of 1 The author must acknowledge with gratitude the several scholars who contributed to this project: Barbara De Marco, Christiane J. Hessler, Peter Humfrey, Francesco S. Minervini, Angela M. Nuovo, Pietro D. Omodeo, Ulrich Pfisterer, Gavriel Shapiro, Graziella Travaglini, Raymond B. Waddington, Kathleen M. Ward and Richard Woodfield. 2 Angelo Borzelli, Bartolommeo Maranta. Difensore del Tiziano, Naples: Gennaro, 1902; Giuseppe Solimene, Un umanista venosino (Bartolomeo Maranta) giudica Tiziano, Naples: Società aspetti letterari, 1952; and Paola Barocchi, ed., Scritti d’arte del Cinquecento, Milan- Naples: Einaudi, 1971, 3 vols, 1:863-900. For the translation click here. Journal of Art Historiography Number 13 December 2015 Luba Freedman Bartolomeo Maranta’s ‘Discourse’ on Titian’s Annunciation in Naples: introduction this text is held in the Biblioteca Nazionale of Naples. The translated title is: ‘A Discourse of Bartolomeo Maranta to the most ill. Sig. Ferrante Carrafa, Marquis of Santo Lucido, on the subject of painting. In which the picture, made by Titian for the chapel of Sig. Cosmo Pinelli, is defended against some opposing comments made by some persons’.3 Maranta wrote the discourse to argue against groundless opinions about Titian’s Annunciation he overheard in the Pinelli chapel. -

Jan Brueghel the Elder: the Entry of the Animals Into Noah's

GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART JAN BRUEGHEL THE ELDER The Entry of the Animals into Noah's Ark Arianne Faber Kolb THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES © 2005 J. Paul Getty Trust Library of Congress Cover and frontispiece: Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jan Brueghel the Elder (Flemish, Getty Publications 1568-1625), The Entry of the Animals 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Kolb, Arianne Faber into Noah's Ark, 1613 [full painting Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 Jan Brueghel the Elder : The entry and detail]. Oil on panel, 54.6 x www.getty.edu of the animals into Noah's ark / 83.8 cm (21/2 x 33 in.). Los Angeles, Arianne Faber Kolb. J. Paul Getty Museum, 92.PB.82. Christopher Hudson, Publisher p. cm. — (Getty Museum Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief studies on art) Page i: Includes bibliographical references Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, Mollie Holtman, Series Editor and index. 1599-1641) and an unknown Abby Sider, Copy Editor ISBN 0-89236-770-9 (pbk.) engraver, Portrait of Jan Brueghel Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 1. Brueghel, Jan 1568—1625. Noah's the Elder, before 1621. Etching and Suzanne Watson, Production ark (J. Paul Getty Museum) engraving, second state, 24.9 x Coordinator 2. Noah's ark in art. 3. Painting— 15.8 cm (9% x 6/4 in.). Amsterdam, Christopher Foster, Lou Meluso, California—Los Angeles. Rijksmuseum, Rijksprentenkabinet, Charles Passela, Jack Ross, 4. J. Paul Getty Museum. I. Title. RP-P-OP-II.II3. Photographers II. Series. ND673.B72A7 2004 Typesetting by Diane Franco 759.9493 dc22 Printed in China by Imago 2005014758 All photographs are copyrighted by the issuing institutions, unless other- wise indicated. -

Exhibition Museum Der Bildenden Künste Leipzig April 18

Exhibition Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig April 18 – August 15, 2010 Neo Rauch Paintings Foreword travelers yet to be identified, or supporters, but they could an evolution in the artist’s work that was formulated with Rauch supported the exhibition and publication with great also be less identifiable feelings, positive or negative, guard- great mastery. We are sincerely grateful to all of them. Such sensitivity from the outset. His personal contribution of ian angels, or recurring nightmares of a life-path that, in the an exhibition project could not be realized without the publishing two lithographs especially for the exhibition Born in Leipzig in 1960, Neo Rauch is undoubtedly the meantime, has covered fifty years. help of third parties. In this case, we have to thank, above venues deserves our utmost appreciation. We are therefore most internationally significant and most discussed German A total of 120 paintings are on view in Leipzig and Munich. all, the Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe: for the support of the extremely grateful to the artist and his wife Rosa Loy. painter of his generation. His paintings are like a theatrum Selected in close cooperation with Neo Rauch, the works exhibition in Leipzig, we are grateful to the Ostdeutsche mundi, overlapping scenes that gradually lend a sur real are taken from a period that began around twenty years Sparkassenstiftung together with the Sparkasse Leipzig; for aura to their formal verism and their narrative. Following ago. Many of the paintings, some of which are large-format the sponsorship of the exhibition in Munich, we are in- Hans-Werner Schmidt the political changes of 1989 and the ensuing great socio- works, have never been shown before in Germany.