Media Integrity Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medijska Regulatorna Tela I Govor Mržnje

C M C M Y K Y K MEDIJSKA REGULATORNA CTP do B2 TELA I 011/242 2298 011/242 GOVOR MRŽNJE Cilj ove publikacije je da doprinese širem razumevanju pojma govora mržnje, da ponudi polaznu osnovu za pripremu preporuka i mehanizama za borbu protiv takvog govora, i da u tom smeru, omogući dalje napore i inicijative. Nadamo se da će ova publikacija biti koristan i važan instrument u daljim aktivnostima, ne samo regulatornih tela za medije, već i ostalih društvenihaktera. Savet Evrope želi da izrazi svoju zahvalnost regulatornim telima u oblasti elektronskih medija iz Jugoistočne Evrope na njihovom učešću u pripremi ove publikacije, posvećenosti, inicijativi, odgovornosti i timskom radu koji su rezultirali izradom ove veoma vredne publikacije. SRB MEDIJSKA REGULATORNA TELA IGOVOR MRŽNJE Savet Evrope je vodeća organizacija za ljudska prava Evropska unija je jedinstveno ekonomsko i političko partnerstvo 28 www.coe.int/en/web/freedom-expression na kontinentu. Obuhvata 47 država, od kojih su 28 demokratskih evropskih zemalja. Njeni ciljevi su mir, prosperitet 300 g • 800 ком. • Sjajna 1/0 Plasfikacija: članice Evropske unije. Sve države članice Saveta i sloboda za njenih 500 miliona građana – u pravednijem Evrope potpisale su Evropsku konvenciju o ljudskim i bezbednijem svetu. Kako bi se to ostvarilo, države članice pravima, sporazum čiji je cilj zaštita ljudskih prava, Evropske unije su uspostavile tela koja vode Evropsku uniju demokratije i vladavine prava. Evropski sud za ljudska i usvajaju njene zakone. Najvažniji su Evropski parlament (koji prava nadgleda primenu Konvencije u državama predstavlja narod Evrope), Savet Evropske unije (koji predstavlja članicama. nacionalne vlade) i Evropska komisija (koja predstavlja zajednički interes Evropske unije). -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Summary of the 9Th Session

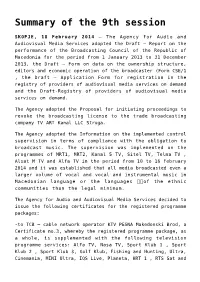

Summary of the 9th session SKOPJE, 18 February 2014 – The Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services adopted the Draft – Report on the performance of the Broadcasting Council of the Republic of Macedonia for the period from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2013, the Draft – Form on data on the ownership structure, editors and economic operation of the broadcaster (Form CSE/1 , the Draft – Application Form for registration in the registry of providers of audiovisual media services on demand and the Draft-Registry of providers of audiovisual media services on demand. The Agency adopted the Proposal for initiating proceedings to revoke the broadcasting license to the trade broadcasting company TV ART Kanal LLC Struga. The Agency adopted the Information on the implemented control supervision in terms of compliance with the obligation to broadcast music. The supervision was implemented on the programmes of MRT1, MRT2, Kanal 5 TV, Sitel TV, Telma TV , Alsat M TV and Alfa TV in the period from 10 to 16 February 2014 and it was established that all media broadcasted even a larger volume of vocal and vocal and instrumental music in Macedonian language or the languages of the ethnic communities than the legal minimum. The Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services decided to issue the following certificates for the registered programme packages: -to TCB – cable network operator KTV PESNA Makedonski Brod, a Certificate no.3, whereby the registered programme package, as a whole, is supplemented with the following television programme services: Alfa TV, Nasa TV, Sport Klub 1 , Sport Klub 2 , Sport Klub 3, Golf Klub, Fishing and Hunting, Ultra, Cinemania, MINI Ultra, IQS Live, Planeta, HRT 1 , RTS Sat and RTCG; – to TCB – cable network operator – KABEL- L- NET, a Certificate no. -

Channel Listล่าสุด2.Xlsx

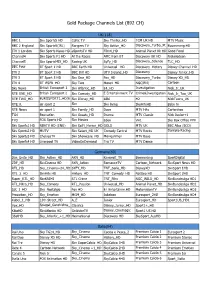

Gold Package Channels List (892 CH) UK(118) BBC 1 Skv Sports5 HD Celtic TV Sky Thriller_HD TCM UK HD MTV Music BBC 2 England Skv Sports5(IRL) Rangers TV Sky Action_HD Discovery_Turbo_Xt Boomerang HD ITV 1 London Skv Sports News HD eSportsTV HD Film4_HD Animal Planet Uk HD Good Food Channel4 Skv Sports F1 HD At the Races AMC from BT Discovery UK HD Nickelodeon Channel5 Skv SportsMIX_HD Racing UK SyFy_HD Discovery_Science TLC_HD BBC Four BT Sport 1 HD BBC Earth HD Universal _HD Discovery_History Disney Channel_HD ITV 2 BT Sport 2 HD BBC Brit HD UTV Ireland_HD Discovery Disney Junior_HD ITV 3 BT Sport 3 HD Skv One_HD Fox_HD Discovery_Turbo Disney XD_HD ITV 4 BT_ESPN_HD Sky Two More4_HD NGC(EN) Cartoon Sky News British Eurosport 1 Skv Atlantic_HD E4_HD Investigation Nick_Jr_UK RTE ONE_HD British Eurosport 2 Skv Comedy_HD E Entertainment TV Crime&Investigation Nick_Jr_Too_UK RTE TWO_HD EUROSPORT1_HD(E Skv Disney_HD Alibi H2 NickToons_UK RTE jr. eir sport 2 Skv Skv living SkyArtsHD Baby tv RTE News eir sport 1 Skv Family_HD Dave MTV Hits Cartonitoo TG4 Boxnation Skv Greats_HD Drama MTV Classic Nick Junior+1 TV3 FOX Sports HD Skv Movies Eden VH1 Sky Box Office PPV Skv Sports1 HD NBATV HD (ENG) Skv SciFi_Horror_HD GOLD MTV UK BBC Alba (SCO) Skv Sports2 HD MUTV Skv Select_HD UK Comedy Central MTV Rocks Dantoto Racing Skv Sports3 HD ChelseaTV Skv Showcase_HD Movies4men MTV Base Skv Sports4 HD Liverpool TV VideoOnDemand Tru TV MTV Dance Germany(69) Das_Erste_HD Sky_Action_HD AXN_HD Kinowelt_TV Boomerang SportDigital ZDF_HD SkvCinema HD AXN_Action -

Media Integrity Matters

a lbania M edia integrity Matters reClaiMing publiC serviCe values in Media and journalisM This book is an Media attempt to address obstacles to a democratic development of media systems in the countries of South East Europe by mapping patterns of corrupt relations and prac bosnia and Herzegovina tices in media policy development, media ownership and financing, public service broadcasting, and journalism as a profession. It introduces the concept of media in tegrity to denote public service values in media and journalism. Five countries were integrity covered by the research presented in this book: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia / MaCedonia / serbia Croatia, Macedonia and Serbia. The research – conducted between July 2013 and February 2014 – was part of the regional project South East European Media Obser vatory – Building Capacities and Coalitions for Monitoring Media Integrity and Ad vancing Media Reforms, coordinated by the Peace Institute in Ljubljana. Matters reClaiMing publiC serviCe values in Media and journalisM Media integrity M a tters ISBN 978-961-6455-70-0 9 7 8 9 6 1 6 4 5 5 7 0 0 ovitek.indd 1 3.6.2014 8:50:48 ALBANIA MEDIA INTEGRITY MATTERS RECLAIMING PUBLIC SERVICE VALUES IN MEDIA AND JOURNALISM Th is book is an attempt to address obstacles to a democratic development of media systems in the MEDIA countries of South East Europe by mapping patterns of corrupt relations and prac- BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA tices in media policy development, media ownership and fi nancing, public service broadcasting, and journalism as a profession. It introduces the concept of media in- tegrity to denote public service values in media and journalism. -

Channels List

INFORMATION COVID19 UPDATE NEWS | NETWORKS NBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBS HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS WGN TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNN HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS CTV NEWS HD NEWS | NETWORKS CP 24 NEWS | NETWORKS BNN NEWS | NETWORKS BLOOMBERG HD NEWS | NETWORKS BBC WORLD NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS MSNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS AL JAZEERA ENGLISH NEWS | NETWORKS FOX Pacific NEWS | NETWORKS WSBK NEWS | NETWORKS CTV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CTV BC NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Winnipeg NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Regina NEWS | NETWORKS CTV OTTAWA HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TWO Ottawa NEWS | NETWORKS CTV EDMONTON NEWS | NETWORKS CBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBC TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CBC News Network NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV BC NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV CALGARY NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CITY TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CITY VANCOUVER NEWS | NETWORKS WBTS NEWS | NETWORKS WFXT NEWS | NETWORKS WEATHER CHANNEL USA NEWS | NETWORKS MY 9 HD NEWS | NETWORKS WNET HD NEWS | NETWORKS WLIW HD NEWS | NETWORKS CHCH NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 1 NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 2 NEWS | NETWORKS THE WEATHER NETWORK NEWS | NETWORKS FOX BUSINESS NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 Miami NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 San Diego NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 12 San Antonio NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 13 HOUSTON NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 2 ATLANTA NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 4 SEATTLE NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 5 CLEVELAND NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 9 ORANDO HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 6 INDIANAPOLIS HD NEWS | NETWORKS -

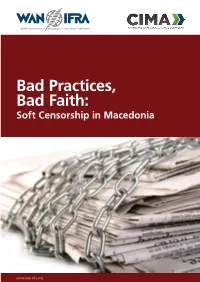

Bad Practices, Bad Faith: Soft Censorship in Macedonia

Bad Practices, Bad Faith: Soft Censorship in Macedonia www.wan-ifra.org Bad Practices, Bad Faith: Soft Censorship in Macedonia PUBLISHER: SEEMO EDITOR: XXXPLEASE MAKE THIS A SMALL TABLE Overview of funds spent in public information campaigns WAN-IFRA Oliver Vujovic 2012 - 6,615,609 EUR World Association of Newspapers 2013 - 7,244,950 EUR and News Publishers OTHER RESEARCH PARTNERS: 2014 – (to 20 June) 3,985,500 EUR 96 bis, Rue Beaubourg International Press Institute (IPI), Vienna Source: Association of Journalists of Macedonia (2015) “Assessment of Media System in Macedonia” 75003 Paris, France International Academy - International Media www.wan-ifra.org Center (IA-IMC), Vienna International Academy (IA), Belgrade WAN-IFRA CEO: Vincent Peyrègne PROJECT PARTNERS: Center for International Media Assistance Soft Censorship in Macedonia: Bad PROJECT MANAGER: National Endowment for Democracy Practices, Bad Faith, is one of a series in the Mariona Sanz Cortell 1025 F Street, N.W., 8th Floor ongoing project on soft censorship around the Washington, DC 20004, USA world. Country reports on Hungary, Malaysia, EDITOR: www.cima.ned.org Mexico, Montenegro and Serbia were issued in Thomas R. Lansner 2013-15, as well as a global overview, Soft Open Society Justice Initiative Censorship, Hard Impact, written by Thomas R PRINCIPAL RESEARCHER: 224 West 57th Street Lansner, who also edited this report and is South East Europe Media Organisation New York, New York 10019, USA general editor for the series. (SEEMO), Vienna www.opensocietyfoundations.org www.seemo.org -

Regulatorni Organi Za Medije I Govor Mržnje

C M C M Y K Y K REGULATORNI ORGANI CTP do B2 ZA MEDIJE 011/242 2298 011/242 I GOVOR MRŽNJE Cilj ove publikacije je da doprinese širem razumijevanju pojma govora mržnje, da ponudi polaznu osnovu za pripremu preporuka i mehanizama za borbu protiv takvog govora, i da u tom smjeru, omogući dalje napore i inicijative. Nadamo se da će ova publikacija biti koristan i važan instrument u daljim aktivnostima, ne samo regulatornih organa za medije, već i ostalih društvenihaktera. Savjet Evrope želi da izrazi svoju zahvalnost regulatornim organima u oblasti elektronskih medija iz Jugoistočne Evrope na njihovom učešću u pripremi ove publikacije, posvećenosti, inicijativi, odgovornosti i timskom radu koji su rezultirali izradom ove veoma vrijedne publikacije. MNE ORGANI ZA MEDIJE I GOVOR MRŽNJE REGULATORNI Savjet Evrope je vodeća organizacija za ljudska prava Evropska unija je jedinstveno ekonomsko i političko www.coe.int/en/web/freedom-expression na kontinentu. Obuhvata 47 država, od kojih partnerstvo 28 demokratskih evropskih zemalja. Njeni ciljevi 300 g • 500 kom. • Sjajna 1/0 Plasfikacija: su 28 članice Evropske unije. Sve države članice su mir, prosperitet i sloboda za njenih 500 miliona građana Savjeta Evrope potpisale su Evropsku konvenciju o – u pravednijem i bezbjednijem svijetu. Kako bi se to ostvarilo, ljudskim pravima, sporazum čiji je cilj zaštita države članice Evropske unije su uspostavile tijela koja vode ljudskih prava, demokratije i vladavine prava. Evropsku uniju i usvajaju njene zakone. Najvažniji su Evropski Evropski sud za ljudska prava nadgleda primjenu parlament (koji predstavlja narod Evrope), Savjet Evropske unije Konvencije u državama članicama. (koji predstavlja nacionalne vlade) i Evropska komisija (koja predstavlja zajedničkii nteres Evropske unije). -

Ponuda S Cjenikom

PONUDA S CJENIKOM TELEVIZIJA Kontakt centar 0800 97 00, [email protected], http://totaltv.tv/hr TV paketi BEZ U.O. U.O. 12 U.O. 24 Opis TV paketa MJESECI MJESECA Osnovni Total TV paket 143.63 kn 110.48 kn 84.99 kn Više od 90 programa (31 HD programa) Osnovni TTV + HBOHD, HBO2 HD, HBO3 HD, Super Total TV 332.65 kn 204.99 kn 135.00 kn CineStar TV Premiere 1 HD i CineStar TV Premiere 2 HD i 1 dodatni prijamnik Dodatni TV paketi BEZ U.O. U.O. 12 MJESECI Opis dodatnih TV paketa HBO 69.10 kn 34.55 kn HBO HD, HBO 2 HD, HBO 3 HD Cinemax 48.7 8 kn 24.39 kn Cinemax, Cinemax 2 Cinestar TV Premiere 69.10 kn 34.55 kn CineStar TV Premiere 1 HD, CineStar TV Premiere 2 HD Prošireni paket 20.3 2 kn 10.16 kn RTS 1, RTS 2, Prva, Prva Plus, Pink 2, O2, Happy, Studio B, K:CN 1, Palma Plus, 24 Vesti, Telma, Kanal 5, Kanal 5+, Sitel, Sitel 3 Pink 81.30 kn 40.65 kn Pink M, Pink, Pink BH, Pink 3 Info, Pink Family, Pink Film, Pink Movies, Pink Action, Pink Plus, Pink Extra, Pink Kids, Pink Music Club x 36.58 kn 18.29 kn DORCEL TV HD, BRAZZERS TV, DUSK, HUSTLER TV FILMBOX EXTRA HD, DOCUBOX HD, FIGHTBOX HD, Film Box 60.00 kn 30.00 kn FAST&FUN BOX HD, FILMBOX PLUS, FILMBOX ARTHOUSE, FASHIONBOX, 360 TUNE BOX, EROX, EROX XXX HD Filmski paket 100.00 kn 50.00 kn HBO HD, HBO 2 HD, HBO 3 HD, CINESTAR TV PREMIERE 1 HD I CINESTAR TV PREMIERE 2 HD Uz osnovne pakete korisnicima su na raspolaganju i slobodni satelitski programi (više od 100 FTA programa) i 11 FTA radio stanica. -

Medijska Kultura 004-2013 .Pdf.Pdf

MEDIJSKA KULTURA Međunarodni (regionalni) naučno stručni časopis MEDIA CULTURE International (regional) scientific journal Redakcija / Editorial board: Budimir Damjanović (Nikšić), Mr Željko Rutović (Podgorica), Janko Nikolovski (Skoplje), dr Đorđe Obradović (Dubrovnik), Mirko Sebić (Novi Sad), dr Zoran Tomić (Mostar) Glavni urednik / Editor: Budimir Damjanović Izdavač/Publisher: NVO Civilni forum Nikšić Grafičko oblikovanje i priprema za štampu / Design and prepress: Veljko Damjanović, Grafička radionicaSPUTNJIK , Novi Sad Adresa i kontakt: Ul. Peka Pavlovića P+4/s Nikšić, Crna Gora e-mail: [email protected] Štampa / Print: IVPE – Cetinje Tiraž / Circulation: 350 primjeraka ISSN 1800-8577 Medijska kultura je regionalni projekat naučnih časopisa MediAnali – Dubrovnik, Mioko – Novi Sad i Medijska politika – Nikšić, osnovan na I Forumu naučnih medijskih časopisa održanom u Mojkovcu 5. i 6. jula 2010. Media culture is regional project of scientific journalsMediAnali – Dubrovnik, Mioko – Novi Sad i Medijska politika – Nikšić, established on I Forum of scientific journals held in Mojkovac on 5th and 6th July of 2010. NAUČNO STRUČNI ČASOPIS IZ OBLASTI MEDIJA NIKŠIĆ + NOVI SAD + DUBROVNIK + MOSTAR Uvodni aspekti na temu: Medijska koncentracija Ne može se dovoljno naglasiti značaj ovog pitanja i temu koju posta- vlja “Medijska kultura”, čija se težina proteže, zadire i utiče na sa me temelje slobode izražavanja misli i informisanja. Položaj i značenje medijske koncentracije zahtijeva već na samome počet- ku nekoliko opštih primjedbi, kao podrška naučnim radovima i aspekata koji slijede na sledećim stranicama. Valja posebno podvući da problematika medijske koncentracije (kao jedna od opasnosti po slobodu u parlamentarnim demokratija- ma) ima svoj kontinuitet u dosadašnjoj uređivačkoj politici cr- nogorskih časopisa i istraživačkih centara posvećenih naučno – stručnim pitanjima iz oblasti medija i istraživanju medija i društva. -

North Macedonia

NORTH MACEDONIA MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2019 Tracking Development of Sustainable Independent Media Around the World NORTH MACEDONIA AT A GLANCE GENERAL MEDIA-SPECIFIC ▶ Population: 2,118,945 (July 2018 est. CIA ▶ Languages (% of population): Macedonian ▶ Number of active print outlets, radio ▶ Newspaper circulation statistics: Sloboden World Factbook) (official) 66.5%, Albanian 25.1%, Turkish 3.5%, stations, television stations, Internet pečat – 12,800, Večer - 7900, Nezavisen vesnik ▶ Capital city: Skopje Romani 1.9%, Serbian 1.2%, other 1.8% (CIA news portals: Print: 5 dailies, 4 weeklies, 29 – 7000, Nova Makedonija – 7500, Koha – 5000 World Factbook, 2002 est.) other periodicals (Registry kept by AVMS); (figures refer to print circulation, figures on ▶ Ethnic groups (% of population): Macedonian 64.2%, Albanian 25.2%, Turkish ▶ GNI (2017 - Atlas): $10.17 billion (World Bank Television: 53 TV broadcasters (AVMS sold copy unavailable) 3.9%, Romani 2.7%, Serb 1.8%, other 2.2% Development Indicators, 2017) Registry) – Public broadcaster MRT (5 ▶ Broadcast ratings: Sitel TV – 24.46%, Kanal channels), 5 DVB-T national broadcasters, (CIA World Factbook, 2002 est.) ▶ GNI per capita (2017 - PPP): $14,680 (World 5 TV – 13.51%, AlsatM TV – 5.56%, Telma 8 national cable and satellite TV stations, 10 TV – 2.85%, TV24 – 2.81%, Alfa – 2.42%, 1TV ▶ Religions (% of population): Macedonian Bank Development Indicators, 2017) regional cable TV stations, 10 regional DVB-T – 1.09% (Nielsen ratings, received through Orthodox 64.8%, Muslim 33.3%, other -

Freedom House, Its Academic Advisers, and the Author(S) of This Report

Macedonia By Jovan Bliznakovski Capital: Skopje Population: 2.08 million GNI/capita, PPP: $14,310 Source: World Bank World Development Indicators. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 National Democratic 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.75 5.00 4.75 Governance Electoral Process 3.50 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.50 3.75 4.00 4.00 Civil Society 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.50 3.25 3.25 3.25 Independent Media 4.25 4.25 4.50 4.75 4.75 5.00 5.00 5.25 5.25 5.00 Local Democratic 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 4.00 4.00 4.00 Governance Judicial Framework 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.50 4.75 4.75 and Independence Corruption 4.25 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.25 4.25 4.50 4.75 4.75 Democracy Score 3.86 3.79 3.82 3.89 3.93 4.00 4.07 4.29 4.43 4.36 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. If consensus cannot be reached, Freedom House is responsible for the final ratings. The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest.