Moths and Butterflies of Keele.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; Download Unter

©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 28, Heft 28: 377-388 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. November 2007 Phytophagous Noctuidae (Lepidoptera) of the Western Black Sea Region and their ichneumonid parasitoids Z. OKYAR & M. YURTCAN Abstract Eleven agricultural and silviculturally important species of Noctuidae and their parasitoids were determined in 33 localities from the Western Black Sea region between 2001 and 2004. The ichneumonid biological control agents Enicospilus ramidulus, Barylypa amabilis and Itoplectis alternans were obtained by rearing the host larvae. K e y w o r d s : Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, parasitoidism, Western Black Sea Region, Turkey Zusammenfassung 11 land- und forstwirtschaftlich bedeutende Noctuidae-Arten einschließlich ihrer Parasitoide aus 33 Standorten des Gebietes des westlichen Schwarzen Meeres wurden im Zeitraum 2001 bis 2004 studiert. Ichneumonidae der Arten Enicospilus ramidulus, Barylypa amabilis and Itoplectis alternans konnten durch Aufzucht der Wirtslarven festgestellt werden. 377 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Introduction The Noctuidae is the largest family of the Lepidoptera. Larvae of some species are par- ticularly harmful to agricultural and silvicultural regions worldwide. Consequently, for years intense efforts have been carried out to control them through chemical, biological, and cultural methods (LIBURD et al. 2000; HOBALLAH et al. 2004; TOPRAK & GÜRKAN 2005). In the field, noctuid control is often carried out by parasitoid wasps (CHO et al. 2006). Ichneumonids are one of the most prevalent parasitoid groups of noctuids but they also parasitize on other many Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera and Araneae (KASPARYAN 1981; FITTON et al. 1987, 1988; GAULD & BOLTON 1988; WAHL 1993; GEORGIEV & KOLAROV 1999). -

Fauna Lepidopterologica Volgo-Uralensis" 150 Years Later: Changes and Additions

©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (August 2000) 31 (1/2):327-367< Würzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 "Fauna lepidopterologica Volgo-Uralensis" 150 years later: changes and additions. Part 5. Noctuidae (Insecto, Lepidoptera) by Vasily V. A n ik in , Sergey A. Sachkov , Va d im V. Z o lo t u h in & A n drey V. Sv ir id o v received 24.II.2000 Summary: 630 species of the Noctuidae are listed for the modern Volgo-Ural fauna. 2 species [Mesapamea hedeni Graeser and Amphidrina amurensis Staudinger ) are noted from Europe for the first time and one more— Nycteola siculana Fuchs —from Russia. 3 species ( Catocala optata Godart , Helicoverpa obsoleta Fabricius , Pseudohadena minuta Pungeler ) are deleted from the list. Supposedly they were either erroneously determinated or incorrect noted from the region under consideration since Eversmann 's work. 289 species are recorded from the re gion in addition to Eversmann 's list. This paper is the fifth in a series of publications1 dealing with the composition of the pres ent-day fauna of noctuid-moths in the Middle Volga and the south-western Cisurals. This re gion comprises the administrative divisions of the Astrakhan, Volgograd, Saratov, Samara, Uljanovsk, Orenburg, Uralsk and Atyraus (= Gurjev) Districts, together with Tataria and Bash kiria. As was accepted in the first part of this series, only material reliably labelled, and cover ing the last 20 years was used for this study. The main collections are those of the authors: V. A n i k i n (Saratov and Volgograd Districts), S. -

Scope: Munis Entomology & Zoology Publishes a Wide Variety of Papers

732 _____________Mun. Ent. Zool. Vol. 7, No. 2, June 2012__________ STRUCTURE OF LEPIDOPTEROCENOSES ON OAKS QUERCUS DALECHAMPII AND Q. CERRIS IN CENTRAL EUROPE AND ESTIMATION OF THE MOST IMPORTANT SPECIES Miroslav Kulfan* * Department of Ecology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Comenius University, Mlynská dolina B-1, SK-84215 Bratislava, SLOVAKIA. E-mail: [email protected] [Kulfan, M. 2012. Structure of lepidopterocenoses on oaks Quercus dalechampii and Q. cerris in Central Europe and estimation of the most important species. Munis Entomology & Zoology, 7 (2): 732-741] ABSTRACT: On the basis of lepidopterous larvae a total of 96 species on Quercus dalechampii and 58 species on Q. cerris were recorded in 10 study plots of Malé Karpaty and Trnavská pahorkatina hills. The families Geometridae, Noctuidae and Tortricidae encompassed the highest number of found species. The most recorded species belonged to the trophic group of generalists. On the basis of total abundance of lepidopterous larvae found on Q. dalechampii from all the study plots the most abundant species was evidently Operophtera brumata. The most abundant species on Q. cerris was Cyclophora ruficiliaria. Based on estimated oak leaf area consumed by a larva it is shown that Lymantria dispar was the most important leaf-chewing species of both Q. dalechampii and Q. cerris. KEY WORDS: Slovakia, Quercus dalechampii, Q. cerris, the most important species. About 300 Lepidoptera species are known to damage the assimilation tissue of oaks in Central Europe (Patočka, 1954, 1980; Patočka et al.1999; Reiprich, 2001). Lepidoptera larvae are shown to be the most important group of oak defoliators (Patočka et al., 1962, 1999). -

Drepanidae (Lepidoptera)

ISSN: 1989-6581 Fernández Vidal (2017) www.aegaweb.com/arquivos_entomoloxicos ARQUIVOS ENTOMOLÓXICOS, 17: 151-158 ARTIGO / ARTÍCULO / ARTICLE Lepidópteros de O Courel (Lugo, Galicia, España, N.O. Península Ibérica) VII: Drepanidae (Lepidoptera). Eliseo H. Fernández Vidal Plaza de Zalaeta, 2, 5ºA. E-15002 A Coruña (ESPAÑA). e-mail: [email protected] Resumen: Se elabora un listado comentado y puesto al día de los Drepanidae (Lepidoptera) presentes en O Courel (Lugo, Galicia, España, N.O. Península Ibérica), recopilando los datos bibliográficos existentes (sólo para dos especies) a los que se añaden otros nuevos como resultado del trabajo de campo del autor alcanzando un total de 13 especies. Entre los nuevos registros aportados se incluyen tres primeras citas para la provincia de Lugo: Drepana curvatula (Borkhausen, 1790), Watsonalla binaria (Hufnagel, 1767) y Cimatophorina diluta ([Denis & Schiffermüller], 1775). Incluimos también nuevas citas de Drepanidae para otras localidades del resto del territorio gallego, entre las que aportamos las primeras de Falcaria lacertinaria (Linnaeus, 1758) para las provincias de Ourense y Pontevedra. Palabras clave: Lepidoptera, Drepanidae, O Courel, Lugo, Galicia, España, N.O. Península Ibérica. Abstract: Lepidoptera from O Courel (Lugo, Galicia, Spain, NW Iberian Peninsula) VII: Drepanidae (Lepidoptera). An updated and annotated list of the Drepanidae (Lepidoptera) know to occur in O Courel (Lugo, Galicia, Spain, NW Iberian Peninsula) is made, compiling the existing bibliographic records (only for two species) and reaching up to 13 species after adding new ones as a result of field work undertaken by the author. Amongst the new data the first records of Drepana curvatula (Borkhausen, 1790), Watsonalla binaria (Hufnagel, 1767) and Cimatophorina diluta ([Denis & Schiffermüller], 1775) for the province of Lugo are reported. -

Thesis.Pdf (3.979Mb)

FACULTY OF BIOSCIENCES, FISHERIES AND ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF ARCTIC AND MARINE BIOLOGY Cyclically outbreaking geometrid moths in sub-arctic mountain birch forest: the organization and impacts of their interactions with animal communities — Ole Petter Laksforsmo Vindstad A dissertation for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor – October 2014 Cyclically outbreaking geometrid moths in sub-arctic mountain birch forest: the organization and impacts of their interactions with animal communities Ole Petter Laksforsmo Vindstad A dissertation for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor University of Tromsø – The arctic university of Norway Faculty of Biosciences, Fisheries and Economics Department of Arctic and Marine Biology Autumn 2014 1 Dedicated to everyone who has helped me along the way 2 Supervisors Professor Rolf Anker Ims1 Senior researcher Jane Uhd Jepsen2 1 Department of Arctic and Marine Biology, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Fram Centre, Tromsø, Norway Cover photos Front cover – Larvae of Epirrita autumnata feeding on mountain birch during a moth outbreak in northern Norway. Photo: Moritz Klinghardt Study I – Portrait of Agrypon flaveolatum. One of the most important larval parasitoid species in study I. Photo: Ole Petter Laksforsmo Vindstad Study II – Carcass of an Operophtera brumata larva, standing over the cocoon of its killer, the parasitoid group Protapanteles anchisiades/P. immunis/Cotesia salebrosa. Photo: Ole Petter Laksforsmo Vindstad Study III – Larva of the parasitoid group Phobocampe sp./Sinophorus crassifemur emerging from Agriopis aurantiaria host larva. Photo: Tino Schott Study IV – An area of healthy mountain birch forest, representative for the undamaged sampling sites in study IV and V. Photo: Jakob Iglhaut Study V – An area of mountain birch forest that has been heavily damaged by a moth outbreak, representative for the damaged sampling sites in study IV and V. -

The Barbastelle in Bovey Valley Woods

The Barbastelle in Bovey Valley Woods A report prepared for The Woodland Trust The Barbastelle in Bovey Valley Woods Andrew Carr, Dr Matt Zeale & Professor Gareth Jones School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Life Sciences Building, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol, BS8 1TQ Report prepared for The Woodland Trust October 2016 Acknowledgements Thanks to: Dave Rickwood of the Woodland Trust for his central role and continued support throughout this project; Dr Andrew Weatherall of the University of Cumbria; Simon Lee of Natural England and James Mason of the Woodland Trust for helpful advice; Dr Beth Clare of Queen Mary University of London for support with molecular work; the many Woodland Trust volunteers and assistants that provided their time to the project. We would particularly like to thank Tom ‘the tracker’ Williams and Mike ‘the trapper’ Treble for dedicating so much of their time. We thank the Woodland Trust, Natural England and the Heritage Lottery Fund for funding this research. We also appreciate assistance from the local landowners who provided access to land. i Contents Acknowledgements i Contents ii List of figures and tables iii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 The Barbastelle in Bovey Valley Woods 2 1.3 Objectives 2 2 Methods 2 2.1 Study area 2 2.2 Bat capture, tagging and radio-tracking 3 2.3 Habitat mapping 4 2.4 Analysis of roost preferences 5 2.5 Analysis of ranges and foraging areas 7 2.6 Analysis of diet 7 3 Results 8 3.1 Capture data 8 3.2 Roost selection and preferences 9 3.3 Ranging and foraging 14 3.4 Diet 17 4 Discussion 21 4.1 Roost use 21 4.2 Ranging behaviour 24 4.3 Diet 25 5 Conclusion 26 References 27 Appendix 1 Summary table of all bat captures 30 Appendix 2 Comparison of individual B. -

![Acronicta Euphorbiae ([Den. & Schiff.], 1775) Beobachtung, Kenntnisstand Und Zucht (Insecta: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0890/acronicta-euphorbiae-den-schiff-1775-beobachtung-kenntnisstand-und-zucht-insecta-lepidoptera-noctuidae-290890.webp)

Acronicta Euphorbiae ([Den. & Schiff.], 1775) Beobachtung, Kenntnisstand Und Zucht (Insecta: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae)

©Kreis Nürnberger Entomologen; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Acronicta euphorbiae ([Den. & Schiff.], 1775) Beobachtung, Kenntnisstand und Zucht (Insecta: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) R u d o l f F r ie d r ic h T a n n e r t Zusammenfassung: Der Verfasser schildert seine Erfahrungen mit Acronicta euphorbiae ([Den. & Schiff.], 1775). Angesprochen werden auch die aus ein schlägiger Literatur gewonnenen Kenntnisse, sowie Erfahrungen mit verschiedenen erfolgreichen aber auch weniger erfolgreichen Zuchten der Art. Abstract: The author informs about his experiences in raising Acronicta euphorbiae ([Den. & Schiff.], 1775), especially about the problem to find the right feeding plant for the Caterpillars. Advices in the basic literature proved to be wrong. Key Words: Noctuidae, Acronicta euphorbiae Namen und Verbreitung Nach neuerer Nomenklatur (K a rsholt & Ra zo w sk i , 1996) trägt die Art den im Titel genannten Namen Acronicta euphorbiae ([Den. & Schiff.], 1775.) In K o ch , 1991 heißt sieAcronycta euphorbiae F., in FÖRSTER & W ohlfah rt , 1979, Pharetra euphorbiae Schiff., weitere frühere Benennungen lauteten Apatele euphorbiae Schiff., Acronycta euphrasiae Brahm, Chamaepora euphorbiae F.. Sicher fanden sich noch einige andere. In „Die Schmetterlinge Baden-Württembergs“, Band 6, Nachtfalter IV, 1997, lautet der deutsche Name „Wolfsmilch-Rindeneule“ A. euphorbiae ist west-palaearktisch verbreitet. In Europa ist sie nach K. & R. aus nahezu allen Ländern gemeldet. Ob sie in Luxemburg, Ungarn und Griechenland vorkommt ist unbekannt. Allerdings liegen Meldungen aus Belgien und den Niederlanden, sowie aus den Ungarn und Griechenland umgebenden Ländern vor. Daher kann angenommen werden, dass die Art in 31 Luxemburg wie auch©Kreis NürnbergerUngarn Entomologen; und Griechenland download unter www.biologiezentrum.at verbreitet ist. -

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry. -

Mass Flow in Hyphae of the Oomycete Achlya Bisexualis

Mass flow in hyphae of the oomycete Achlya bisexualis A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Cellular and Molecular Biology in the University of Canterbury by Mona Bidanjiri University of Canterbury 2018 Abstract Oomycetes and fungi grow in a polarized manner through the process of tip growth. This is a complex process, involving extension at the apex of the cell and the movement of the cytoplasm forward, as the tip extends. The mechanisms that underlie this growth are not clearly understood, but it is thought that the process is driven by the tip yielding to turgor pressure. Mass flow, the process where bulk flow of material occurs down a pressure gradient, may play a role in tip growth moving the cytoplasm forward. This has previously been demonstrated in mycelia of the oomycete Achlya bisexualis and in single hypha of the fungus Neurospora crassa. Microinjected silicone oil droplets were observed to move in the predicted direction after the establishment of an imposed pressure gradient. In order to test for mass flow in a single hypha of A. bisexualis the work in this thesis describes the microinjection of silicone oil droplets into hyphae. Pressure gradients were imposed by the addition of hyperosmotic and hypoosmotic solutions to the hyphae. In majority of experiments, after both hypo- and hyperosmotic treatments, the oil droplets moved down the imposed gradient in the predicted direction. This supports the existence of mass flow in single hypha of A. bisexualis. The Hagen-Poiseuille equation was used to calculate the theoretical rate of mass flow occurring within the hypha and this was compared to observed rates. -

(Insecta, Lepidoptera) Национального Парка «Анюйский» (Хабаровский Край) В

Амурский зоологический журнал, 2020, т. XII, № 4 Amurian Zoological Journal, 2020, vol. XII, no. 4 www.azjournal.ru УДК 595.783 DOI: 10.33910/2686-9519-2020-12-4-490-512 http://zoobank.org/References/b28d159d-a1bd-4da9-838c-931ed5c583bb MACROHETEROCERA (INSECTA, LEPIDOPTERA) НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ПАРКА «АНЮЙСКИЙ» (ХАБАРОВСКИЙ КРАЙ) В. В. Дубатолов1, 2 1 ФГУ «Заповедное Приамурье», ул. Юбилейная, д. 8, Хабаровский край, 680502, пос. Бычиха, Россия 2 Институт систематики и экологии животных СО РАН, ул. Фрунзе, д. 11, 630091, Новосибирск, Россия Сведения об авторе Аннотация. Приводится список Macroheterocera (без Geometridae), Дубатолов Владимир Викторович отмеченных в Анюйском национальном парке, включающий 442 вида. E-mail: [email protected] Наиболее интересные находки: Rhodoneura vittula Guenée, 1858; Auzata SPIN-код: 6703-7948 superba (Butler, 1878); Oroplema plagifera (Butler, 1881); Mimopydna pallida Scopus Author ID: 14035403600 (Butler, 1877); Epinotodonta fumosa Matsumura, 1920; Moma tsushimana ResearcherID: N-1168-2018 Sugi, 1982; Chilodes pacifica Sugi, 1982; Doerriesa striata Staudinger, 1900; Euromoia subpulchra (Alpheraky, 1897) и Xestia kurentzovi (Kononenko, 1984). Среди них впервые для Приамурья приводятся Rhodoneura vittula Guen. (Thyrididae), Euromoia subpulchra Alph. и Xestia kurentzovi Kononenko (Noctuidae). Права: © Автор (2020). Опубликова- но Российским государственным Ключевые слова: Macroheterocera, Nolidae, Limacodidae, Cossidae, педагогическим университетом им. Thyrididae, Thyatiridae, Drepanidae, Uraniidae, Lasiocampidae, -

TWO NEW SPECIES of MOTHS (NOCTUIDAE: ACRONICTINAE, CUCULLIINAE) from MIDLAND UNITED STATES Since Their Origins, the Ohio Lepidop

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 46(3), 1992, 220-232 TWO NEW SPECIES OF MOTHS (NOCTUIDAE: ACRONICTINAE, CUCULLIINAE) FROM MIDLAND UNITED STATES CHARLES y, COVELL JR. Department of Biology, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky 40292 AND ERIC H. METZLER Ohio Department of Natural Resources, 1952 Belcher Drive, Columbus, Ohio 43224 ABSTRACT. Two new species of noctuid moths are described and illustrated. Ac ronicta heitzmani, new species, in the subfamily Acronictinae, is known from Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois and Ohio. Lithophane joannis, new species, in the subfamily Cucul Iiinae, is known from Ohio, Kentucky, and Michigan. Both species are compared with morphologically similar congeners. Additional key words: Acronicta heitzmani, Lithophane joannis, faunal survey. Since their origins, the Ohio Lepidopterists and the Society of Ken tucky Lepidopterists ha ve promoted regional surveys of the Lepidoptera fauna of midland United States. These efforts have resulted in numerous new records and range extensions and in the discovery of several new taxa, The purpose of this paper is to describe and illustrate two recently discovered species of the family Noctuidae. Both apparently are re stricted to midland United States, Acronicta heitzmani, new species, is known from Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois and Ohio. Lithophane joan nis, new species, is known from Ohio, Kentucky, and Michigan. Both species are morphologically distinct from, and sympatric with, con geners, In 1964, J. R, Heitzman collected a series of an unusual Acronicta species in Missouri. The specimens superficially resembled A. fragilis (Guenee) which was not recorded from Missouri. In 1967, the first author collected a specimen of the same species in Kentucky; the second author took the first Ohio specimen in 1975, The specimens were de termined as a possibly undescribed species near A. -

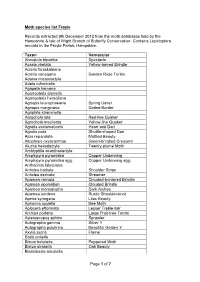

Page 1 of 7 Moth Species List Froyle Records

Moth species list Froyle Records extracted 9th December 2012 from the moth databases held by the Hampshire & Isle of Wight Branch of Butterfly Conservation. Contains Lepidoptera records in the Froyle Parish, Hampshire. Taxon Vernacular Abrostola tripartita Spectacle Acasis viretata Yellow-barred Brindle Acleris forsskaleana Acleris variegana Garden Rose Tortrix Adaina microdactyla Adela rufimitrella Agapeta hamana Agonopterix arenella Agonopterix heracliana Agriopis leucophaearia Spring Usher Agriopis marginaria Dotted Border Agriphila straminella Agrochola lota Red-line Quaker Agrochola macilenta Yellow-line Quaker Agrotis exclamationis Heart and Dart Agrotis puta Shuttle-shaped Dart Alcis repandata Mottled Beauty Allophyes oxyacanthae Green-brindled Crescent Alucita hexadactyla Twenty-plume Moth Amblyptilia acanthadactyla Amphipyra pyramidea Copper Underwing Amphipyra pyramidea agg. Copper Underwing agg. Anthophila fabriciana Anticlea badiata Shoulder Stripe Anticlea derivata Streamer Apamea crenata Clouded-bordered Brindle Apamea epomidion Clouded Brindle Apamea monoglypha Dark Arches Apamea sordens Rustic Shoulder-knot Apeira syringaria Lilac Beauty Aphomia sociella Bee Moth Aplocera efformata Lesser Treble-bar Archips podana Large Fruit-tree Tortrix Asteroscopus sphinx Sprawler Autographa gamma Silver Y Autographa pulchrina Beautiful Golden Y Axylia putris Flame Batia unitella Biston betularia Peppered Moth Biston strataria Oak Beauty Blastobasis adustella Page 1 of 7 Blastobasis lacticolella Cabera exanthemata Common Wave Cabera