Phelsuma ISSN 1026-5023 Volume 9 (Supplement A) 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

§4-71-6.5 LIST of CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November 28, 2006 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Plesiopora FAMILY Tubificidae Tubifex (all species in genus) worm, tubifex PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Crustacea ORDER Anostraca FAMILY Artemiidae Artemia (all species in genus) shrimp, brine ORDER Cladocera FAMILY Daphnidae Daphnia (all species in genus) flea, water ORDER Decapoda FAMILY Atelecyclidae Erimacrus isenbeckii crab, horsehair FAMILY Cancridae Cancer antennarius crab, California rock Cancer anthonyi crab, yellowstone Cancer borealis crab, Jonah Cancer magister crab, dungeness Cancer productus crab, rock (red) FAMILY Geryonidae Geryon affinis crab, golden FAMILY Lithodidae Paralithodes camtschatica crab, Alaskan king FAMILY Majidae Chionocetes bairdi crab, snow Chionocetes opilio crab, snow 1 CONDITIONAL ANIMAL LIST §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Chionocetes tanneri crab, snow FAMILY Nephropidae Homarus (all species in genus) lobster, true FAMILY Palaemonidae Macrobrachium lar shrimp, freshwater Macrobrachium rosenbergi prawn, giant long-legged FAMILY Palinuridae Jasus (all species in genus) crayfish, saltwater; lobster Panulirus argus lobster, Atlantic spiny Panulirus longipes femoristriga crayfish, saltwater Panulirus pencillatus lobster, spiny FAMILY Portunidae Callinectes sapidus crab, blue Scylla serrata crab, Samoan; serrate, swimming FAMILY Raninidae Ranina ranina crab, spanner; red frog, Hawaiian CLASS Insecta ORDER Coleoptera FAMILY Tenebrionidae Tenebrio molitor mealworm, -

Husbandry and Captive Breeding of the Bated by Slow Or Indirect Shipping

I\IJtIlD AND T'II'LT' Iil1,TUKTS j r8- I.r I o, ee+,, JilJilill fl:{:r;,i,,'J,:*,1;l: dehydration, and thermal exposure of improper or protracted warehousing on either or both sides of the Atlantic, exacer- Husbandry and Captive Breeding of the bated by slow or indirect shipping. These situations may also Parrot-Beaked Tortoise, have provided a dramatic stress-related increase in parasite Homopus areolatus or bacterial loads, or rendered pathogens more virulent, thereby adversely affecting the health and immunity levels Jnuns E. BIRZYKI of the tortoises. With this in mind, 6 field-collected tortoises | (3 project 530 l,{orth Park Roacl, Lct Grctnge Pcrrk, Illinois 60525 USA males, 3 females) used in this were airfreighted directly from South Africa to fully operational indoor cap- The range of the parrot-beaked tortoise, Hontopus tive facilities in the USA. A number of surplus captive areolatus, is restricted to the Cape Province in South Africa specirnens (7) were also available, and these were included (Loveridge and Williams, 1957; Branch, 1989). It follows in the study group. the coastline of the Indian Ocean from East London in the Materials ancl MethocLr. - Two habitat enclosures mea- east, around the Cape of Good Hope along the Atlantic surin-e 7 x2 feet (2.1 x 0.6 m) were constructed of plywood Ocean, north to about Clanwilliam. This ran-qe is bordered in and each housed two males and either four or five females. the northeast by the very arid Great Karoo, an area receiving These were enclosed on all sides, save for the front, which less than 250 mm of rain annually, and in the north by the had sliding ..elass doors. -

Body Condition Assessment – As a Welfare and Management Assessment Tool for Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys Radiata)

Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management assessment tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Independent project • 15 hp Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SLU Department of Animal Environment and Health Programme/Education Uppsala 2020 2 Body condition assessment – as a welfare and management tool for radiated tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) Hullbedömning - som ett verktyg för utvärdering av välfärd och skötsel av strålsköldpadda (Astrochelys radiata) Linn Lagerström Supervisor: Lisa Lundin, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Examiner: Maria Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Environment and Health Credits: 15 hp Level: First cycle, G2E Course title: Independent project Course code: EX0894 Programme/education: Course coordinating dept: Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2020 Cover picture: Linn Lagerström Keywords: Tortoise, turtle, radiated tortoise, Astrochelys radiata, Geochelone radiata, body condition indices, body condition score, morphometrics Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Animal Environment and Health 3 Publishing and archiving Approved students’ theses at SLU are published electronically. As a student, you have the copyright to your own work and need to approve the electronic publishing. If you check the box for YES, the full text (pdf file) and metadata will be visible and searchable online. If you check the box for NO, only the metadata and the abstract will be visiable and searchable online. Nevertheless, when the document is uploaded it will still be archived as a digital file. -

Chelonian Perivitelline Membrane-Bound Sperm Detection: a New Breeding Management Tool

Zoo Biology 35: 95–103 (2016) RESEARCH ARTICLE Chelonian Perivitelline Membrane-Bound Sperm Detection: A New Breeding Management Tool Kaitlin Croyle,1,2 Paul Gibbons,3 Christine Light,3 Eric Goode,3 Barbara Durrant,1 and Thomas Jensen1* 1San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Escondido, California 2Department of Biological Sciences, California State University San Marcos, San Marcos, California 3Turtle Conservancy, New York, New York Perivitelline membrane (PVM)-bound sperm detection has recently been incorporated into avian breeding programs to assess egg fertility, confirm successful copulation, and to evaluate male reproductive status and pair compatibility. Due to the similarities between avian and chelonian egg structure and development, and because fertility determination in chelonian eggs lacking embryonic growth is equally challenging, PVM-bound sperm detection may also be a promising tool for the reproductive management of turtles and tortoises. This study is the first to successfully demonstrate the use of PVM-bound sperm detection in chelonian eggs. Recovered membranes were stained with Hoechst 33342 and examined for sperm presence using fluorescence microscopy. Sperm were positively identified for up to 206 days post-oviposition, following storage, diapause, and/or incubation, in 52 opportunistically collected eggs representing 12 species. However, advanced microbial infection frequently hindered the ability to detect membrane-bound sperm. Fertile Centrochelys sulcata, Manouria emys,andStigmochelys pardalis eggs were used to evaluate the impact of incubation and storage on the ability to detect sperm. Storage at À20°C or in formalin were found to be the best methods for egg preservation prior to sperm detection. Additionally, sperm-derived mtDNA was isolated and PCR amplified from Astrochelys radiata, C. -

English and French Cop17 Inf

Original language: English and French CoP17 Inf. 36 (English and French only / Únicamente en inglés y francés / Seulement en anglais et français) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 JOINT STATEMENT REGARDING MADAGASCAR’S PLOUGHSHARE / ANGONOKA TORTOISE 1. This document has been submitted by the United States of America at the request of the Wildlife Conservation Society, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Turtle Survival Alliance, and The Turtle Conservancy, in relation to agenda item 73 on Tortoises and freshwater turtles (Testudines spp.)*. 2. This species is restricted to a limited range in northwestern Madagascar. It has been included in CITES Appendix I since 1975 and has been categorized as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species since 2008. There has been a significant increase in the level of illegal collection and trafficking of this species to supply the high end pet trade over the last 5 years. 3. Attached please find the joint statement regarding Madagascar’s Ploughshare/Angonoka Tortoise, which is considered directly relevant to Document CoP17 Doc. 73 on tortoises and freshwater turtles. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. -

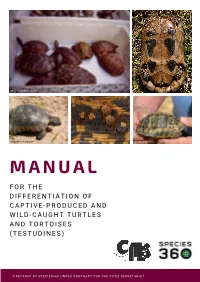

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

University of Nevada, Reno Effects of Fire on Desert Tortoise (Gopherus Agassizii) Thermal Ecology a Dissertation Submitted in P

University of Nevada, Reno Effects of fire on desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) thermal ecology A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology by Sarah J. Snyder Dr. C. Richard Tracy/Dissertation Advisor May 2014 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by SARAH J. SNYDER Entitled Effects of fire on desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) thermal ecology be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY C. Richard Tracy, Ph.D., Advisor Kenneth Nussear, Ph.D., Committee Member Peter Weisberg, Ph.D., Committee Member Lynn Zimmerman, Ph.D., Committee Member Lesley DeFalco, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2014 i ABSTRACT Among the many threats facing the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) is the destruction and alteration of habitat. In recent years, wildfires have burned extensive portions of tortoise habitat in the Mojave Desert, leaving burned landscapes that are virtually devoid of living vegetation. Here, we investigated the effects of fire on the thermal ecology of the desert tortoise by quantifying the thermal quality of above- and below-ground habitat, determining which shrub species are most thermally valuable for tortoises including which shrub species are used by tortoises most frequently, and comparing the body temperature of tortoises in burned and unburned habitat. To address these questions we placed operative temperature models in microhabitats that received filtered radiation to test the validity of assuming that the interaction between radiation and radiation-absorbing properties of the model can result in a single, mean radiant absorptance regardless of whether the incident solar radiation is direct unfiltered or filtered by plant canopies, using the desert tortoise as a case study. -

Aldabrachelys Arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold's Giant Tortoise

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectTestudinidae of the IUCN/SSC — AldabrachelysTortoise and Freshwater arnoldi Turtle Specialist Group 028.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, P.C.H. Pritchard, P.P. van Dijk, R.A. Saumure, K.A. Buhlmann, J.B. Iverson, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.028.arnoldi.v1.2009 © 2009 by Chelonian Research Foundation • Published 18 October 2009 Aldabrachelys arnoldi (Bour 1982) – Arnold’s Giant Tortoise JUSTIN GERLACH 1 1133 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge CB1 7BX, United Kingdom [[email protected]] SUMMARY . – Arnold’s giant tortoise, Aldabrachelys arnoldi (= Dipsochelys arnoldi) (Family Testudinidae), from the granitic Seychelles, is a controversial species possibly distinct from the Aldabra giant tortoise, A. gigantea (= D. dussumieri of some authors). The species is a morphologi- cally distinctive morphotype, but has so far not been genetically distinguishable from the Aldabra tortoise, and is considered synonymous with that species by many researchers. Captive reared juveniles suggest that there may be a genetic basis for the morphotype and more detailed genetic work is needed to elucidate these relationships. The species is the only living saddle-backed tortoise in the Seychelles islands. It was apparently extirpated from the wild in the 1800s and believed to be extinct until recently purportedly rediscovered in captivity. The current population of this morphotype is 23 adults, including 18 captive adult males on Mahé Island, 5 adults recently in- troduced to Silhouette Island, and one free-ranging female on Cousine Island. Successful captive breeding has produced 138 juveniles to date. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

Origins of Endemic Island Tortoises in the Western Indian Ocean: a Critique of the Human-Translocation Hypothesis

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Origins of endemic island tortoises in the western Indian Ocean: a critique of the human-translocation hypothesis Hansen, Dennis M ; Austin, Jeremy J ; Baxter, Rich H ; de Boer, Erik J ; Falcón, Wilfredo ; Norder, Sietze J ; Rijsdijk, Kenneth F ; Thébaud, Christophe ; Bunbury, Nancy J ; Warren, Ben H Abstract: How do organisms arrive on isolated islands, and how do insular evolutionary radiations arise? In a recent paper, Wilmé et al. (2016a) argue that early Austronesians that colonized Madagascar from Southeast Asia translocated giant tortoises to islands in the western Indian Ocean. In the Mascarene Islands, moreover, the human-translocated tortoises then evolved and radiated in an endemic genus (Cylindraspis). Their proposal ignores the broad, established understanding of the processes leading to the formation of native island biotas, including endemic radiations. We find Wilmé et al.’s suggestion poorly conceived, using a flawed methodology and missing two critical pieces of information: the timing and the specifics of proposed translocations. In response, we here summarize the arguments thatcould be used to defend the natural origin not only of Indian Ocean giant tortoises but also of scores of insular endemic radiations world-wide. Reinforcing a generalist’s objection, the phylogenetic and ecological data on giant tortoises, and current knowledge of environmental and palaeogeographical history of the Indian Ocean, make Wilmé et al.’s argument even more unlikely. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12893 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-131419 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Hansen, Dennis M; Austin, Jeremy J; Baxter, Rich H; de Boer, Erik J; Falcón, Wilfredo; Norder, Sietze J; Rijsdijk, Kenneth F; Thébaud, Christophe; Bunbury, Nancy J; Warren, Ben H (2017). -

Universidad Nacional Del Comahue Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche

Universidad Nacional del Comahue Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche Título de la Tesis Microanatomía y osteohistología del caparazón de los Testudinata del Mesozoico y Cenozoico de Argentina: Aspectos sistemáticos y paleoecológicos implicados Trabajo de Tesis para optar al Título de Doctor en Biología Tesista: Lic. en Ciencias Biológicas Juan Marcos Jannello Director: Dr. Ignacio A. Cerda Co-director: Dr. Marcelo S. de la Fuente 2018 Tesis Doctoral UNCo J. Marcos Jannello 2018 Resumen Las inusuales estructuras óseas observadas entre los vertebrados, como el cuello largo de la jirafa o el cráneo en forma de T del tiburón martillo, han interesado a los científicos desde hace mucho tiempo. Uno de estos casos es el clado Testudinata el cual representa uno de los grupos más fascinantes y enigmáticos conocidos entre de los amniotas. Su inconfundible plan corporal, que ha persistido desde el Triásico tardío hasta la actualidad, se caracteriza por la presencia del caparazón, el cual encierra a las cinturas, tanto pectoral como pélvica, dentro de la caja torácica desarrollada. Esta estructura les ha permitido a las tortugas adaptarse con éxito a diversos ambientes (por ejemplo, terrestres, acuáticos continentales, marinos costeros e incluso marinos pelágicos). Su capacidad para habitar diferentes nichos ecológicos, su importante diversidad taxonómica y su plan corporal particular hacen de los Testudinata un modelo de estudio muy atrayente dentro de los vertebrados. Una disciplina que ha demostrado ser una herramienta muy importante para abordar varios temas relacionados al caparazón de las tortugas, es la paleohistología. Esta disciplina se ha involucrado en temas diversos tales como el origen del caparazón, el origen del desarrollo y mantenimiento de la ornamentación, la paleoecología y la sistemática.