Unraveling the Gordian Knot of Implicit Bias in Jury Selection: the Problems of Judge- Dominated Voir Dire, the Failed Promise of Batson, and Proposed Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar Daniel A

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Doctor of Ministry Theses Student Theses 2002 Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar Daniel A. Rakotojoelinandrasana Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/dmin_theses Part of the Christianity Commons, Mental and Social Health Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Rakotojoelinandrasana, Daniel A., "Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar" (2002). Doctor of Ministry Theses. 19. http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/dmin_theses/19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOLISTIC APPROACH TO MENTAL ILLNESSES AT THE TOBY OF AMBOHIBAO MADAGASCAR by DANIEL A. RAKOTOJOELINANDRASANA A Thesis Submitted to, the Faculty of Luther Seminary And The Minnesota Consortium of Seminary Faculties In Partial Fulfillments of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS ADVISOR: RICHARD WALLA CE. SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA 2002 LUTHER SEMINARY USRARY 22-75Como Aver:ue 1 ©2002 by Daniel Rakotojoelinandrasana All rights reserved 2 Thesis Project Committee Dr. Richard Wallace, Luther Seminary, Thesis Advisor Dr. Craig Moran, Luther Seminary, Reader Dr. J. Michael Byron, St. Paul Seminary, School of Divinity, Reader ABSTRACT The Church is to reclaim its teaching and praxis of the healing ministry at the example of Jesus Christ who preached, taught and healed. Healing is holistic, that is, caring for the whole person, physical, mental, social and spiritual. -

Techniques and Tips for Raising Implicit Bias in Court: Use of Videos, Jury Instructions, and Voir Dire

Techniques and Tips for Raising Implicit Bias in Court: Use of Videos, Jury Instructions, and Voir Dire Selected Materials From Multiple Presenters Lisa Hay Federal Public Defender TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Materials for Further Self-Study and Education ............................................................. 1 2. Proposed Oregon Unconscious Bias Jury Instruction s...................................................... 3 3. Ninth Circuit Model Instructions..................................................................................... 4. Can Explicit Instructions Reduce Expression of Implicit Bias? ...................................... 5 5. Bar Bulletin, King County Bar Association .................................................................. 35 6. US v. Jacorey Sanders Motion for Attorney Conducted Voir Dire on Implicit Bias and Memorandum in Support ........................................................................................ 37 7. Excerpts of Voir Dire Questions .................................................................................... 55 8. Raising Unconscious Bias in Voir Dire ......................................................................... 70 9. Achieving an Impartial Jury (AIJ) Toolbox ................................................................... 71 10. A New Approach to Voir Dire on Racial Bias, UC Irvine Law Review ...................... 139 Materials for Further Self-Study and Education* Justice Adrienne Nelson Unconscious Bias Video for Jurors A direct link to the video: Understanding -

The Grief Edition 90 Editorial Note: the Content for This Edition of New Therapist Was Coordinated and Managed by Darcy EDITOR Harris, One of the Contributors

NewIndispensable survival guide for Therapistthe thinking psychotherapist March/April 2014 The Grief Edition 90 Editorial note: The content for this edition of New Therapist was coordinated and managed by Darcy EDITOR Harris, one of the contributors. We are deeply John Söderlund grateful to Darcy for generously providing her astute and efficient editorial management of thisedition. MANAGING EDITOR Lee-ann Bailey FEATURES EDITOR Features Sue Spencer CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 6 Good Grief: A Contemporary Dylan Evans Orientation to Bereavement Graham Lindegger Jacqui de Mare Counseling Julie Manegold Tim Barry Robert A. Neimeyer with John Tom Strong Kelly Quayle Soderlund Robert Langs Simone Descoins Robert Waska A fate less than death: 14 CONTRIBUTIONS Supporting clients through non- Submissions for inclusion in New Therapist are welcomed. death loss and grief New Therapist reserves the right to edit or exclude any submission. Names and identifying information of all individuals mentioned in case material have been changed to By Darcy Harris protect their identities. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of New Therapist, its publishers or distributors. Coming to grief: What you ADVERTISING 20 need to know about grief in Advertising deadlines for New Therapist are six weeks prior to the first Monday of the month of publication. Please call or DSM-5 email for a media pack and rate card, or visit our web site at www.NewTherapist.com. By Phyllis Kosminsky SUBSCRIPTIONS Subscription charges are $48 per year to all international destinations (including postage). To South African Getting grief working: A guide destinations, subscription charges are R320 per year 25 (including VAT and postage). -

Psychometric Properties and Adaptation of the Self-Concealment Scale to the Turkish Adolescents*

Elementary Education Online, 9(1), 424–432, 2010. lköretim Online, 9(1), 424-432, 2010. [Online]: http://ilkogretim-online.org.tr Psychometric Properties and Adaptation of the Self-Concealment Scale to the Turkish Adolescents* Metin Deniz** Figen Çok*** ABSTRACT. The objective of this study was to adaptate the Self Concealment Scale (SCS) developed by Larson and Chastain (1990) to Turkish adolescents. The original scale is in English and consists of 10 items. Firstly, the original scale was translated into Turkish by six experts from the field and retranslated by two experts. Also, the original and Turkish forms of the scale were handed to the experts in the field of measurement and evaluation and the last form of the scale was carried out in the light of their opinions. The Turkish version of the SCS was administrated to 370 students (aged 14–18 years), attending 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th grades in Ankara, Turkey. Findings regarding the construct validity of the scale were rather consistent with the original scale’s one factor structure. The Cronbach Alpha internal consistency of the scale was 0.86 for this sample. Key words: Self concealment, Adolescence, Factor Analysis SUMMARY Purpose and Significance: Secrecy is crucial in human life, particularly during adolescence. It is thought to be related to some physical and psychological disadvantages such as physical complaints, headaches, anxiety,depression etc., in the earlier studies. However, new researchers seem to indicate that secrecy may also have important developmental functions in the period of adolescence. Secrecy is a new research area in this perspective everywhere as well as in Turkey. -

Living, Dying, Death, and Bereavement (Volume One)

Living, Dying, Death, and Bereavement (Volume One) Living, Dying, Death, and Bereavement (Volume One): Conversations with Thanatologists By David E. Balk Foreword by Paul C. Rosenblatt Living, Dying, Death, and Bereavement (Volume One): Conversations with Thanatologists By David E. Balk This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by David E. Balk All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5958-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5958-5 This book is dedicated to Mary Ann Balk and to Janet Renee Balk, my wife and my daughter, in thankfulness for and appreciation of their savvy, grit, love, support, courage, help, intelligence, senses of humor, commitment to achieving social justice, and fervent outspokenness about equality. Each has core values and beliefs by which she leads her life. My heart smiles when each enters a room where I am. Also this book is dedicated to the administrators, faculty, and staff of Brooklyn College, particularly to the faculty and staff of the Department of Health and Nutrition Sciences, who made welcome during 15 productive years at CUNY a wandering thanatologist from the wilds of the American Midwest. I appreciate the trust and friendship you offered. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................. -

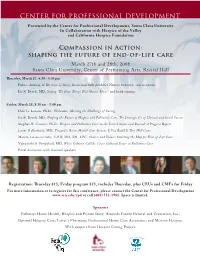

Center for Professional Development

CENTER FOR PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Presented by the Center for Professional Development, Santa Clara University In Collaboration with Hospice of the Valley and California Hospice Foundation Compassion in Action: shaping the future of end-of-life care March 27th and 28th, 2008 Santa Clara University, Center of Performing Arts, Recital Hall ursday, March 27, 4:30 - 8:00 pm Public showing of e Gifts of Grief, discussion with producer Nancee Sobonya, and reception Ira R. Byock, MD, Saying “e Four ings at Matter Most,” and book signing Friday, March 28, 8:30 am - 5:00 pm Dale G. Larson, Ph.D., Welcome, Meeting the Challenge of Caring Ira R. Byock, MD, Shaping the Future of Hospice and Palliative Care: e Strategic C’s of Clinical and Social Success Stephen R. Connor, Ph.D., Hospice and Palliative Care in the United States and Beyond: A Progress Report James Hallenbeck, MD, Toward a Better Health Care System: If You Build It ey Will Come Marcia Lattanzi-Licht, LHD, MA, RN, LPC, Choices and Values: Charting the Map for End-of-Life Care Vyjeyanthi S. Periyakoil, MD, When Cultures Collide: Cross-Cultural Issues in Palliative Care Panel discussion with featured speakers. Registration: ursday $15; Friday program $55, includes ursday, plus CEUs and CMEs for Friday For more information or to register for this conference, please contact the Center for Professional Development www.scu.edu/cpd or call (408) 551-1981. Space is limited. Sponsors Pathways Home Health, Hospice and Private Duty; Alameda Family Funeral and Cremation, Inc.; Optimal Hospice Care; Leiter’s Pharmacy; Professional Home Care Associates; and Mission Hospice. -

CPSY Masters Program's Classes at SCU, Students Are Regularly Assigned Work That Involves Self-Disclosure and Personal Study of the Content of That Self-Disclosure

1 Ψ 228 ADVANCED COUNSELING PROCESS AND SKILLS DR. DALE LARSON Santa Clara University, Winter, 2020 Class meets January 25/26, and February 8/9 from 9am-6pm in Guadalupe Hall 150, 151 Office hours: Tuesdays, 1:30-4:30, with 3:30-4:30 for walk-ins Office: Guadalupe 124 E-mail: [email protected] Office: 408.554.4320 Emergency: 408.806.4743 OBJECTIVES ● Identify and develop advanced individual counseling skills ● Explore and learn techniques for working effectively with process dimensions of therapy, including resistance, emotional dysregulation, transference, countertransference ● Expand understanding of theory and techniques of integrative psychotherapy, with special emphasis on the process-experiential and interpersonal process approaches presented in the texts for the class, which range from emotion-focused to objection relations to schema therapy and control mastery approaches. ● Enhance self-observation skills through live feedback, and supervision of in-class counseling experiences REQUIREMENTS Class attendance (No misses allowed. If you will miss a day, or half-day, do not enroll in the • class). A final paper due Monday, finals week. • Completion of training exercises during class • Passing grade (80% correct) on multiple choice take-home exam on Teyber text. The exam • is due the morning of Day 3. Class graded Pass/Fail • CLASSROOM ETIQUETTE ● While in class please show respect to fellow students and the instructor by turning off wireless access for all electronic devices (e.g., laptop, tablet, phone, etc). All devices allow you to do this. You can use airplane mode if your device has that setting. For people in 2 caregiving roles who must be available in case of an emergency, cell phones can be set to vibrate. -

Commencement Exercise Programs, 2004

ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-NINTH fpWlgy Brigham Young University Marriott Center Thursday, April 22, 2004 Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/commencementexer2004brig ONE HUNDRED AND T W E N T Y- N I N T H fpWWy Brigham Young University Marriott Center Thursday, April 22, 2004 Contents Order of the Academic Procession 4 Significance of the Academic Costume 4 Program 5 Commencement Speaker 6 Doctoral Degrees 7 Master's Degrees 13 Certificates 35 Baccalaureate Degrees 37 Scholastic Recognition 73 Graduates with University Honors 73 Summa Cum Laude 75 Magna Cum Laude 75 Cum Laude 76 Phi Kappa Phi 78 Air Force and Army ROTC Graduates 80 College Convocation Schedule 81 Commencement Committees 82 Academic Procession Order of the Academic Procession Significance of the Academic Costume President, Board of Trustees, and Administrative Officers The significance of the academic Official Guests costume is determined especially by the Faculty sleeves and hoods. Candidates for Advanced Degrees Doctors wear the round bell sleeve; of Class 2004 the gown is faced down the front and barred on the sleeves with black velvet or color indicating the degree; the doctor's hood is large. The doctor may choose to wear the gold tassel on the cap. Masters wear the long, closed sleeve, with a slit near the upper part of the arm; the master's hood is of more moderate size. Bachelors wear the long or pointed sleeve. The color of the tassel indicates whether the degree is in the field of arts (white), fine arts (brown), music (pink), or science (golden yellow). -

HELPING MOURNERS DEAL with JEALOUSY, GUILT and SHAME in BEREAVEMENT Self-Study ONLINE Course

Hospice Foundation of America’s Program HELPING MOURNERS DEAL WITH JEALOUSY, GUILT AND SHAME IN BEREAVEMENT Self-Study ONLINE Course DESCRIPTION Grieving people may experience surprising and unsettling emotions after a death including jealousy, guilt and shame. This webinar will offer interventive strategies to help grieving individuals recognize, validate, and resolve such complicated reactions. PROGRAM DETAILS Hospice Foundation of America has taken its popular webinar program and created a self- study course for professionals. The online presentation features experienced professionals offering their own expertise on the topic. On the screen, you will see the slide presentation and will be able to hear the experts talking and presenting. RELEASE DATE: Program originally premiered October 17, 2017 ON DEMAND: to registered individuals for 1 year after purchase LENGTH: 90 minutes CE HOURS: 1.5 hours for a wide variety of professional boards CE FEE: One CE certificate is included in the cost of registration. Additional certificates (if selecting more than one board) are $10 each. CONTENT LEVEL: The program is mainly for professionals already working in the field, but is practical for all levels of education – entry level, intermediate or advanced. TARGET AUDIENCE: The course is useful to Health care clinicians, social service clinicians and others working in the hospice, palliative care, counseling, hospital, nursing home, funeral home or faith community environments HOW THE ONLINE SELF-STUDY PROGRAM WORKS: Step 1 - Register/purchase the course Step 2 - View the course online through the link in your confirmation email or in your account. Step 3 - Follow the instructions provided to receive your CE certificate*. -

Vita Dale Larson 5.1.19

DALE G. LARSON, PH.D Santa Clara University Department of Counseling Psychology 500 El Camino Real Guadalupe Hall 124 Santa Clara, CA. 95053-0201 Office Phone: (408) 554-4320 Cell Phone: (408) 806-4743 Fax: (408) 554-2392 E-mail: [email protected] Professor, Department of Counseling Psychology, Santa Clara University, 2003-present (Associate Professor, 1988-2003) (Assistant Professor, 1982-1988) Interim Dean, School of Education, Counseling Psychology, and Pastoral Ministries, Santa Clara University, 6/07-6/08 Chairperson, Department of Counseling Psychology, Santa Clara University, 1998-2001 Markkula Center Scholar, 1995-present EDUCATION Ph.D., Clinical Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, December 10, 1977 M.A., Clinical Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, June 15, 1974 B.A., Psychology, University of Chicago, June 12, 1971 HONORS Death Educator Award, Association for Death Education and Counseling, 2016 Fellow, Division 32, Humanistic Psychology, 2016 Fellow, Division 38, Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 2009 Fellow, Division 17, Counseling Psychology, American Psychological Association, 2008 2007 Kara Pioneer Award, “In recognition of pioneering work in end-of-life care,” Palo Alto, CA, 11/2/2007 2007 Hospice Award of Excellence. This award honors individuals or organizations that have made a significant difference in the arena of hospice care. Award presented March 20, 2007, Hospice of Northeastern Illinois, Barrington, Illinois. Award of Excellence recipient for the National Hospice Organization’s 1997 Awards of Excellence for Educational Achievement Competition for Innovative Use of Non-Print Media/Electronic Media. The Hospice Home Page was recognized on October 16, 1997 at a special awards ceremony at NHO’s Annual Symposium and Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia. -

Christopher Alexander, Cedric Price, and Nicholas Negroponte & Mit’S Architecture Machine Group

ARCHITECTURES OF INFORMATION: CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER, CEDRIC PRICE, AND NICHOLAS NEGROPONTE & MIT’S ARCHITECTURE MACHINE GROUP Volume 1 Molly Wright Steenson A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE Adviser: M. Christine Boyer April 2014 © Copyright by Molly Wright Steenson, 2014. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................... iii Abstract ........................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... vi Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Dissecting “Architectures of Information” .......................................................... 5 Cybernetics, Heuristics, and Artificial Intelligence ............................................ 8 Precedent Use of “Architectures of Information” ............................................ 12 Anti-Architects and Anti-Architecture ............................................................... 16 Organization of the Dissertation ........................................................................ 27 Chapter 1 Christopher Alexander: Trees, Semilattices, and Networks ............ 31 Trees -

Official Newsletter of the American Psychological Association, Division 38 Official Newsletter of the American Psychological Association, Division 38

Volume 31, No. 3 Fall 2009 Official Newsletter of the American Psychological Association, Division 38 Official Newsletter of the American Psychological Association, Division 38 Inside this issue: President‘s Column Student Representa- 3 The Biopsychosocial Model for All tives Jerry Suls, Ph.D. Awards 4-8 ―When there is no vision, the people perish.‖ Diversity Council 9 While traveling by train across Canada to- the past; in fact, ward Toronto for APA‘s annual meeting, I there are few faculty Health Psychology 10 had time to reflect as I gazed at the beauty of who now feel com- Editor the Canadian Rockies and the golden canola fortable or compe- New Fellows 12 fields of Saskatchewan. The upcoming tent to teach them. meeting led to thoughts about health psychol- If they were still of- Council Report 17 ogy and its role in psychology more gener- fered, one would ally. Like many others, I worry about the need so many in- Graduate Student 19 forces experienced by psychology. There is structors to cover the Research Award increasing specialization in some subfields to material it would resemble a faculty meet- the extent that graduate students in one train- ing (who would want that!). Eventually, ing area of a department may scarcely under- the course would become so hard to sched- stand or respect what the students in other ule and negotiate, it would evolve into a areas are doing. ―Systems and theories pro-seminar with each faculty member tak- courses,‖ once a staple and requirement of (Continued on page 2) graduate study in Psychology, are things of From the Assistant Editor‘s Desk H1N1 Vaccination, Anyone? Lisa Marie Frantsve, PhD I have regular media attention concerning ports combined with an implicit been in- this new potential pandemic.