Caroline Wogan Durieux, the Works Progress Administration, and the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOR 15-Final.Pdf

New Orleans Review Spring 1988 Editors John Biguenet· John Mosier Managing Editor Sarah Elizabeth Spain Design Vilma Pesciallo Contributing Editors Bert Cardullo David Estes Jacek Fuksiewicz Alexis Gonzales, F.S.C. Bruce Henricksen Andrew Horton Peggy McCormack Rainer Schulte Founding Editor Miller Williams Advisory Editors Richard Berg Doris Betts Joseph Fichter, S.J. John Irwin Murray Krieger Frank Lentricchia Raymond McGowan Wesley Morris Walker Percy Herman Rapaport Robert Scholes Marcus Smith Miller Williams The New Orleans Review is published by Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118, United States. Copyright© 1988 by Loyola University. Critical essays relating to film or literature of up to ten thousand words should be prepared to conform with the new MLA guidelines and sent to the appropriate editor, together with a stamped, self-addressed envelope. The address is New Orleans Review, Box 195, Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118. Fiction, poetry, photography or related artwork should be sent to the Art and Literature Editor. A stamped, self-addressed envelope should be enclosed. Reasonable care is taken in the handling of material, but no responsibility is assumed for the loss of unsolicited material. Accepted manuscripts are the property of the NOR. The New Orleans Review is published in February, May, August, and November. Annual Subscription Rate: Institutions $30.00, Individuals $25.00, Foreign Subscribers $35.00. Contents listed in the PMLA Bibliography and the Index of American Periodical Verse. US ISSN 0028-6400 Photographs of Gwen Bristow, Ada Jack Carver, Dorothy Dix, and Grace King are reproduced courtesy the Historic New Orleans Collection, Museum/Research Center, Acc. -

To Improve the Qualityof Life for All Citizens of Our Area, Now

Dear Friends, Thanks to the efforts of many, the region served by the Greater New Orleans Foundation has begun a journey up from hurricane-inflicted disaster toward hope. to improve the of It is not an easy path, nor is it for the faint of heart. At times it feels like a quality yearlong sprint or a marathon that will last many years. But signs are everywhere that you and the great people of southeastern Louisiana are more than able. In for all citizens of our area, this report you will see signs in the hands of children, who are the best reason for life imagining—and creating—a livable, economically strong community. When Hurricane Katrina’s wind and floodwaters subsided, it became clear that generations of leaders and supporters of the Greater New Orleans Foundation had now and for future generations put the organization in a unique position. Now, it would be called upon to play both traditional and completely unexpected new roles in the recovery. Thanks to that history of support, to more than $25 million in new gifts and this is where we belong we are pledges from organizations and individuals, and to the way political, business and nonprofit leaders turned to the Foundation for leadership, the Greater New Orleans Foundation is poised to lead in the years ahead. home to stay in New Orleans We believe that creating a dynamic future for the region depends on three key areas of focus: a skilled workforce; safe, affordable neighborhoods; and great pub- lic schools. Since Katrina, the Foundation’s Board and staff have embraced the role of devoting their efforts to achieving and measuring success in those areas. -

Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection

Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection Williams Research Center Historic New Orleans Collection 410 Chartres Street New Orleans, LA 70130 Telephone number: (504) 598-7171 Fax: (504) 598-7168 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.hnoc.org Contact person: Alfred Lemmon Access privileges: Open to the public Hours: Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Repository Information: The Historic New Orleans Collection was established in 1966 by General and Mrs. L. Kemper Williams, private collectors, to maintain and expand their collections and to make them available to the public through research facilities and exhibitions. The Williams Research Center offers scholars access to the extensive print and microform holdings of its three Divisions. The Manuscript collections include letters, diaries, land tenure records, financial and legal documents, records of community organizations, New Orleans newspapers (1803 - present), and annotated printed items. These papers illuminate life in New Orleans and southern social and cultural history in the surrounding areas during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Women are represented throughout the Division's. Although the material listed in this guide is located within the Manuscripts Division, the other divisions also have significant holdings by and about women. The Curatorial Division has many paintings, drawings, photographs, and other three-dimensional objects by women. Information on these female artists, is contained in the division's artists' files. Collection highlights: Significant collections include the Wilkinson-Stark papers especially for their coverage of Mary Farrar Stark Wilkinson's subversion of the invading federal army to protect her children, and the correspondence of Eliza Jane Nicholson, owner and editor of the Times-Picayune in the 1870s and 1880s. -

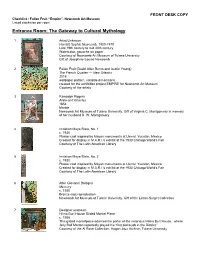

Checklist by Room

FRONT DESK COPY Checklist - Fallen Fruit “Empire”, NewcomB Art Museum Listed clockwise per room Entrance Room: The Gateway to Cultural Mythology 1 Artist Unknown Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870 Late 19th century to mid 20th century Watercolor, gouache on paper Courtesy of Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University Gift of Josephine Louise Newcomb 2 Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young) The French Quarter — New Orleans 2018 wallpaper pattern, variable dimensions created for the exhibition project EMPIRE for Newcomb Art Museum Courtesy of the artists 3 Randolph Rogers Atala and Chactas 1854 Marble Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of Virginia C. Montgomery in memory of her husband R. W. Montgomery 4 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 1 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 5 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 2 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 6 After Giovanni Bologna Mercury c. 1580 Bronze cast reproduction Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of the Linton-Surget Collection 7 Designer unknown Hilma Burt House Gilded Mantel Piece c. 1906 This gilded mantelpiece adorned the parlor of the notorious Hilma Burt House, where Jelly Roll Morton reportedly played his “first piano job in the District.” Courtesy of the Al Rose Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University 8 Casting by the Middle American Research Institute Cast inspired by architecture of the Governor’s Place of Uxmal, Yucatán, México c.1932 Plaster, created for A Century oF Progress Exposition (also known as The Chicago World’s Fair of 1933), M.A.R.I. -

Violent Crime, Moral Transformation, and Urban Redevelopment in Post-Katrina New Orleans

THE BLESSED PLACEMAKERS: VIOLENT CRIME, MORAL TRANSFORMATION, AND URBAN REDEVELOPMENT IN POST-KATRINA NEW ORLEANS by Rebecca L. Carter A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Gillian Feeley-Harnik, Chair Professor Thomas E. Fricke Associate Professor Stuart A. Kirsch Associate Professor Paul Christopher Johnson © Rebecca L. Carter All rights reserved 2010 DEDICATION For Evan ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There aren‟t enough words to fully express my gratitude for the guidance, encouragement, and generous support I have received during the completion of this dissertation and my doctoral degree. It has been a long but extremely rewarding process; an endeavor that has unfolded over the span of the last six years. Of that time, three years were spent completing coursework and training at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; two years (July 2007 – July 2009) were spent doing ethnographic fieldwork in New Orleans, Louisiana; and the final year was spent writing up in my home state of Tennessee, as part of a dissertation writing and teaching fellowship based at Middle Tennessee State University. To be afforded the time and the occasion to work as an anthropologist and ethnographer at all is something of a luxury; I frequently remind myself what a dream job and a privilege it is. There are many people that I must thank for the opportunity, and for their help in seeing the research through until the end. So many, that in many ways the finished product is perhaps best situated as a collective and collaborative project rather than a solo venture. -

Art Trails in Alabama Public Art Members Alabama State Council on the Arts

ALABAMA Volume XXI, Number 2ARTS Art Trails in Alabama Public Art Members Alabama State Council on the Arts BERNICE PRICE CHAIRMAN Montgomery REBECCA T. B. QUINN VICE CHAIRMAN Huntsville FRANK HELDERMAN SECRETARY Florence EVELYN ALLEN Birmingham JULIE HALL FRIEDMAN Fairhope RALPH FROHSIN, JR. Alexander City DOUG GHEE Anniston ELAINE JOHNSON Dothan DORA JAMES LITTLE Auburn JUDGE VANZETTA PENN MCPHERSON Montgomery VAUGHAN MORRISSETTE Mobile DYANN ROBINSON Tuskegee JUDGE JAMES SCOTT SLEDGE Gadsden CEIL JENKINS SNOW Birmingham CAROL PREJEAN ZIPPERT Eutaw Opinions expressed in AlabamaArts do not necessarily reflect those of the Alabama State Council on the Arts or the State of Alabama. ALABAMAARTS In this Issue Volume XXI Public Art Trails in Alabama Number 2 Public Art in Alabama 3 Al Head, Executive Director, ASCA 4 Discovering Public Art: Public Art Trails in Alabama Georgine Clarke, Visual Arts Program Manager, ASCA 6 Continuing the Trail New Deal Art in Alabama Post Offices 42 and Federal Buildings On the cover: Roger Brown Autobiography in the Shape of Alabama (Mammy’s Door) (recto), 1974 Oil on canvas, mirror, wood, Plexiglas, photographs, postcards, and cloth shirt 89 x 48 x 18 inches Collection of Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, gift of Maxine and Jerry Silberman Photography © Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago ©The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Brown family. Roger Brown, (1941-1997) was born in Hamilton, Alabama and later moved to Opelika. From the 1960’s he made his home in Chicago, where he graduated from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and played a significant role in the city’s art scene for over 30 years as one of the Chicago Imagist artists. -

BEACON PRESS Random House Adult Green

BEACON PRESS Random House Adult Green Omni, Fall 2013 Beacon Press Gaga Feminism : Sex, Gender, and the End of Summary: A roadmap to sex and gender for the twenty- Normal first century, using Lady Gaga as a symbol for a new kind J. Jack Halberstam of feminism 9780807010976 Pub Date: 9/3/13, On Sale Date: 9/3 Why are so many women single, so many men resisting $16.00/$18.00 Can. marriage, and so many gays and lesbians having babies? 184 pages Paperback / softback / Trade paperback (US) In Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender, and the End of Normal, J. Social Science / Gender Studies Jack Halberstam answers these questions while attempting to Territory: World except United Kingdom make sense of the tectonic cultural shifts that have Ctn Qty: 24 transformed gender and sexual politics in the last few 5.500 in W | 8.500 in H decades. This colorful landscape is popula... 140mm W | 216mm H Author Bio: J. Jack Halberstam is the author of four books, including Female Masculinity and The Queer Art of Failure. Currently a professor of American studies and of ethnicity and gender studies at the University of Southern California, Halberstam regularly speaks and writes on queer culture and gender issues and blogs at BullyBloggers. Random House Adult Green Omni, Fall 2013 Beacon Press The Long Walk to Freedom : Runaway Slave Summary: In this groundbreaking compilation of first-person Narratives accounts of the runaway slave phenomenon, editors Devon Devon W. Carbado, Donald Weise W. Carbado and Donald Weise have recovered twelve 9780807069097 narratives spanning eight decades-more than half of which Pub Date: 9/3/13, On Sale Date: 9/3 have been long out of print. -

The Best of The

THE BEST OF THE ™ CHANUKAH 2014 / 5775 New Orleans Holocaust Memorial by Yaacov Agam Photo by Hunter Thomas Photography New Orleans U NDERDOGS? Never underestimate the resilient spirit of New Orleanians. The Jewish New Orleans community only totaled about a decisive victory at the Battle of New Orleans was quite the ego dozen men when the Louisiana Purchase was signed in 1803. boast for the underdog militia. It was a banner of pride to be However there are indications that they were quite comfortable worn proudly that, no matter what the obstacles, success would and connected in their newly adopted home. A decade later—at come to those fi ghting on the right side. the Battle of New Orleans most of these same Jewish men were fi ghting alongside Andrew Jackson’s troops defending and pro- Although the Crescent City Jewish News website is about tecting their beloved hometown of New Orleans. four years old, our commitment to the New Orleans Jewish community through our print issues is in its second year. This Who were these men who settled into the New Orleans com- publication—The Best of the Crescent City Jewish News – is the munity more than two centuries ago? First, of all , they were third issue of our semi-annual publications, which document the men seeking economic opportunities to improve their fi nancial events of the past several months. With each publication, we are well being and social standing. They voluntarily relocated from reaching more of our core local Jewish audience. Like those brave large Northeast and New England communities fi lled with the Jewish defenders of New Orleans from a previous century, we are security of their family and friends to an isolated region full of also proud to acknowledge that each new publication affords us high humidity, swamps teeming with alligators and disease car- invaluable recognition from our fellow journalists on the quality rying mosquitoes. -

Chipman, Fanny S

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Program Foreign Service Spouse Series FANNY S. CHIPMAN Interviewed by: Hope Meyers Initial interview date: July 22, 1987 TABLE OF CONTENTS Mrs. Chipman was born and raised in France. In 1935 she married United States Foreign Service Officer Norris Chipman, and accompanied him on his various assignments in Washington, DC and abroad Early years in France Born Fanny Bunand-Sevastos, 1905 in Asniéres, France Raised in France Bourdelle family Bourdelle’s :”La France” Early life in France French artists and writers Early education in France Alice Pike Barney and family Mademoiselle Laprévotte Anatole France Sir James Fraser Musée Bourdelle Career as artist (painter) Marcel Poncet Queen of Belgium Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels The Dying Centaur Posing for sculpture Gift of the head of “France” sculpture Visit to the United States c1928 New York banking society Friend Irene Millet Chandler Bragdcon Georgia O’Keefe Theodor Gréppo 1 Return to Paris La Revue de la Femme Doris Stevens Malone Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact Mrs. O.H.P. Belmont Rambouillet Chateau Women’s Rights meeting Return to U.S. New Orleans carnival Angela Gregory Rodin Inter-American Commission of Women: Staff member The Hague Doris Stevens Malone National Women’s Party Dr. James Brown Scott Lobbying activities Senator Cooper Bernita Matthews Montevideo Conference Haiti Appointed Haiti delegate Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt opposition Protective legislation for women Commission financing Lima Conference Painting career Frau Conrad Husband Norris Chipman Accompanying Foreign Service Officer Norris Chipman 1936-1957 Husband’s background Marriage, 1935 Washington, D.C. -

1 Volume 67, Number 2, Summer 2019

Volume 67, Number 2, Summer 2019 President’s Column…………………….………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 Articles Academic Library & Athletics Partnerships: A Literature Review on Outreach Strategies and Development Opportunities A. Blake Denton…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……3 They Do It Here: A Case Study of How Public Space is Used in a Research Library Ashley S. Dees…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………10 Undergraduate Student Works in Institutional Repositories: An Analysis of Coverage, Prominence and Discoverability Angel Clemons and Tyler Goldberg……………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………….22. News Items SELA/Library News..........................................................................................................................................................................................29 Personnel News………………………………………………………………………………………………………. …………………........29 Book Reviews Seeking Eden: A Collection of Georgia’s Historic Gardens Review by Melinda F. Matthews…..……………………………………………………………………………………………...…………...34 How to Lead When You’re Not in Charge: Leveraging Influence When You Lack Authority Review by Mark A. Krikley……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………35 Southern Women in the Progressive Era: A Reader Review by Carol Walker Jordan………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..35 Blackbeard’s Sunken Prize: The 300-year Voyage of Queen Anne’s Revenge Review by Melanie Dunn………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………36 The Consequences of Loyalism: Essays in Honor of Robert -

Blast from the Past 2020: Made in Louisiana Five Days of Fun Activities to Do at Home

Blast from the Past 2020: Made in Louisiana Five Days of Fun Activities to Do at Home Handcrafted: Art Made in Louisiana Prehistoric Art: Artifacts from Poverty Point and the Medora Site Native Americans inhabited the area we now know as West Baton Rouge Parish since pre-history. Many different tribes occupied area either as roaming tribes or in villages. One site dating from 1200-1400, known at the Medora Site, was located on the southern end of West Baton Rouge parish. The Medora Site was quite complex/sophisticated and consisted of 2 pyramid shaped mounds separated by a large plaza. Archaeologists uncovered lots of pieces of pottery, some stone tools and arrow points. The pottery found at these sites showed a lot of artistry; decorated inside and out. Pieces found were possibly used as jars. The decorations were carved into the unfired clay with sticks, shells or points. Then the clay was fired to harden it for use as a household item. Another important site was in North Louisiana now known as Poverty Point. This site dates to between 1650 and 700 B.C. It consists of ~900 acres of earthworks—mostly platform mounds and ridges. Poverty Point is now a National Monument and a UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) World Heritage site. In the style of the native peoples who walked this land before us, let’s sink our hands into some clay to make and decorate vessels. Make a Clay Pinch Pot Supplies: Clay or Play-Dough Tools such as small sticks or shells for carving Directions 1. -

April 18, 2015

APRIL 18, 2015 2015 TULANE UNIVERSITY ALUMNI AWARDS GALA The National WWII Museum U.S. Freedom Pavilion Saturday, April 18, 2015 PROGRAM Reception 7 pm Dinner & Program 8 pm WELCOME Carol Showley, NC ’74, A ‘77 President, Tulane Alumni Association PRESENTATION OF THE COLORS Tulane University Navy R.O.T.C. Green Wave Brass Band PRESENTATION OF THE TULANE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION AWARDS PRESENTATION OF THE DERMOT MCGLINCHEY LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD PRESENTATION OF THE DISTINGUISHED ALUMNUS AWARD TULANE ALMA MATER Green Wave Brass Band DISTINGUISHED ALUMNUS AWARD COL. DOUGLAS G. HURLEY, USMC, RET. E ‘88 Colonel Douglas G. Hurley, USMC, Ret., is a NASA astronaut, test pilot and fighter pilot with a distinguished military career that spans almost 25 years. Hurley chose to attend Tulane University because of the storied reputation of the engineering program, but found the cultural experience of New Orleans and the discipline of the Navy ROTC program just as important in his eventual career as an astronaut. Hurley had always been interested in flight and space, and his father suggested he study engineering at Tulane. The Marine option of the Navy ROTC program provided the necessary scholarship support that allowed him to pursue his degree. He worked closely with Professor Robert Bruce, himself a Tulane alumnus (E ’51, ’53), who served as a mentor and inspiration. When he graduated magna cum laude with a BSE in civil engineering in 1988, he also he received his commission as a Second Lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps. A few short years later he became a “Viking” with Marine All Weather Fight/Attack Squadron 225, where he was an F/A-18 fighter pilot.