Integrity and Service...The Life of Felix J. Dreyfous, 1857—1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Improve the Qualityof Life for All Citizens of Our Area, Now

Dear Friends, Thanks to the efforts of many, the region served by the Greater New Orleans Foundation has begun a journey up from hurricane-inflicted disaster toward hope. to improve the of It is not an easy path, nor is it for the faint of heart. At times it feels like a quality yearlong sprint or a marathon that will last many years. But signs are everywhere that you and the great people of southeastern Louisiana are more than able. In for all citizens of our area, this report you will see signs in the hands of children, who are the best reason for life imagining—and creating—a livable, economically strong community. When Hurricane Katrina’s wind and floodwaters subsided, it became clear that generations of leaders and supporters of the Greater New Orleans Foundation had now and for future generations put the organization in a unique position. Now, it would be called upon to play both traditional and completely unexpected new roles in the recovery. Thanks to that history of support, to more than $25 million in new gifts and this is where we belong we are pledges from organizations and individuals, and to the way political, business and nonprofit leaders turned to the Foundation for leadership, the Greater New Orleans Foundation is poised to lead in the years ahead. home to stay in New Orleans We believe that creating a dynamic future for the region depends on three key areas of focus: a skilled workforce; safe, affordable neighborhoods; and great pub- lic schools. Since Katrina, the Foundation’s Board and staff have embraced the role of devoting their efforts to achieving and measuring success in those areas. -

Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection

Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection Williams Research Center Historic New Orleans Collection 410 Chartres Street New Orleans, LA 70130 Telephone number: (504) 598-7171 Fax: (504) 598-7168 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.hnoc.org Contact person: Alfred Lemmon Access privileges: Open to the public Hours: Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Repository Information: The Historic New Orleans Collection was established in 1966 by General and Mrs. L. Kemper Williams, private collectors, to maintain and expand their collections and to make them available to the public through research facilities and exhibitions. The Williams Research Center offers scholars access to the extensive print and microform holdings of its three Divisions. The Manuscript collections include letters, diaries, land tenure records, financial and legal documents, records of community organizations, New Orleans newspapers (1803 - present), and annotated printed items. These papers illuminate life in New Orleans and southern social and cultural history in the surrounding areas during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Women are represented throughout the Division's. Although the material listed in this guide is located within the Manuscripts Division, the other divisions also have significant holdings by and about women. The Curatorial Division has many paintings, drawings, photographs, and other three-dimensional objects by women. Information on these female artists, is contained in the division's artists' files. Collection highlights: Significant collections include the Wilkinson-Stark papers especially for their coverage of Mary Farrar Stark Wilkinson's subversion of the invading federal army to protect her children, and the correspondence of Eliza Jane Nicholson, owner and editor of the Times-Picayune in the 1870s and 1880s. -

Checklist by Room

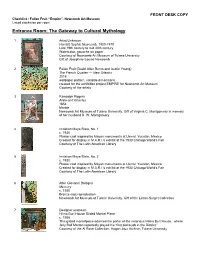

FRONT DESK COPY Checklist - Fallen Fruit “Empire”, NewcomB Art Museum Listed clockwise per room Entrance Room: The Gateway to Cultural Mythology 1 Artist Unknown Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870 Late 19th century to mid 20th century Watercolor, gouache on paper Courtesy of Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University Gift of Josephine Louise Newcomb 2 Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young) The French Quarter — New Orleans 2018 wallpaper pattern, variable dimensions created for the exhibition project EMPIRE for Newcomb Art Museum Courtesy of the artists 3 Randolph Rogers Atala and Chactas 1854 Marble Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of Virginia C. Montgomery in memory of her husband R. W. Montgomery 4 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 1 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 5 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 2 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 6 After Giovanni Bologna Mercury c. 1580 Bronze cast reproduction Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of the Linton-Surget Collection 7 Designer unknown Hilma Burt House Gilded Mantel Piece c. 1906 This gilded mantelpiece adorned the parlor of the notorious Hilma Burt House, where Jelly Roll Morton reportedly played his “first piano job in the District.” Courtesy of the Al Rose Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University 8 Casting by the Middle American Research Institute Cast inspired by architecture of the Governor’s Place of Uxmal, Yucatán, México c.1932 Plaster, created for A Century oF Progress Exposition (also known as The Chicago World’s Fair of 1933), M.A.R.I. -

Art Trails in Alabama Public Art Members Alabama State Council on the Arts

ALABAMA Volume XXI, Number 2ARTS Art Trails in Alabama Public Art Members Alabama State Council on the Arts BERNICE PRICE CHAIRMAN Montgomery REBECCA T. B. QUINN VICE CHAIRMAN Huntsville FRANK HELDERMAN SECRETARY Florence EVELYN ALLEN Birmingham JULIE HALL FRIEDMAN Fairhope RALPH FROHSIN, JR. Alexander City DOUG GHEE Anniston ELAINE JOHNSON Dothan DORA JAMES LITTLE Auburn JUDGE VANZETTA PENN MCPHERSON Montgomery VAUGHAN MORRISSETTE Mobile DYANN ROBINSON Tuskegee JUDGE JAMES SCOTT SLEDGE Gadsden CEIL JENKINS SNOW Birmingham CAROL PREJEAN ZIPPERT Eutaw Opinions expressed in AlabamaArts do not necessarily reflect those of the Alabama State Council on the Arts or the State of Alabama. ALABAMAARTS In this Issue Volume XXI Public Art Trails in Alabama Number 2 Public Art in Alabama 3 Al Head, Executive Director, ASCA 4 Discovering Public Art: Public Art Trails in Alabama Georgine Clarke, Visual Arts Program Manager, ASCA 6 Continuing the Trail New Deal Art in Alabama Post Offices 42 and Federal Buildings On the cover: Roger Brown Autobiography in the Shape of Alabama (Mammy’s Door) (recto), 1974 Oil on canvas, mirror, wood, Plexiglas, photographs, postcards, and cloth shirt 89 x 48 x 18 inches Collection of Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, gift of Maxine and Jerry Silberman Photography © Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago ©The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Brown family. Roger Brown, (1941-1997) was born in Hamilton, Alabama and later moved to Opelika. From the 1960’s he made his home in Chicago, where he graduated from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and played a significant role in the city’s art scene for over 30 years as one of the Chicago Imagist artists. -

1 Louisiana Boys: Raised on Politics by Paul Steckler, Louis Alvarez, and Andrew Kolker, Video, 52 Rnins., 1991

L OUISIANALYSIS A FILM& VIDEOSURVEY curated by Reni Broussard Presented by HALLWALLSCONTEMPORARY ARTS CENTER & THENEW ORLEANS WOMEN'S CAUCUS FOR THE ARTS Sponsored by Cinema 16, New Orleans New Orleans Film & Video Society New Orleans Video Access Center (NOVAC) Squeaky Wheel/Buffalo Media Resources Special thanks to Dean Pascal, Mary Jane Parker, Rebecca Drake, and Video Alternatives October 19 & 20,1992 HALLWALLS CONTEMPORARYARTS CENTER Buffalo, New York December 5 - 12,1992 This program is sponsored by the Arts Council of New Orleans with funds provided by the City of New Orleans Municipal Endowment Grants for the Arts from annual payments in the fran- chise of Cox Cable New Orleans, administered by the New Orleans Women's Caucus for the Arts. THEHALLWALLS FILM PROGRAMis supported by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, the City of Buffalo, and the County of Erie, and by a grant from The John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Catalog written & edited by Reni Broussard Design by Paul Szpakowski innocent little comedy, The Gun In Betty Lou's Handbag, that actu- ally included reference to the dreaded "Cajun Mafia." I haven't met a cajun, myself included, who could ever keep a secret much have never claimed to be from Louisiana although I was born less an entire syndicate. The Louisiana of Hollywood is good oY and raised there and have lived there most of my life. I've boys and bad little girls, voodoo queens and killer cajuns. The list is always said instead, "I'm from New Orleans," hoping people incredible: Southern Comfort, The Big Easy,JFK, Angel Heart, Pretty wouldn't make the connection. -

RESTLESS BLOOD Frans Blom, Explorer and Maya Archaeologist

RESTLESS BLOOD Frans Blom, Explorer and Maya Archaeologist High resolution version and version in single pages for printing available at www.mesoweb.com/publications/Blom Tore Leifer Jesper Nielsen Toke Sellner Reunert RESTLESS BLOOD Frans Blom,Explorer and Maya Archaeologist With a preface by Michael D. Coe Middle American Research Institute Tulane University, New Orleans Precolumbia Mesoweb Press San Francisco Contents 6 Author biographies 7 Acknowledgements 8 Preface by Michael D. Coe 10 Introduction: A Life 13 Chapter 1. A Wealthy Merchant’s Son (1893-1919) 38 Chapter 2. Revolution and Rebels (1919) 58 Chapter 3. Oil, Jungles and Idols of Stone (1919-1922) 90 Chapter 4. The Right Track (1922-1924) 120 Chapter 5. The Great Expeditions (1925-1931) 163 Chapter 6. A Temple in Tulane (1932-1943) 197 Chapter 7. Return to the Great Forests (1943-1944) 219 Chapter 8. A Lady in Gray Flannel (1944-1950) 262 Chapter 9. Na Bolom – House of the Jaguar (1950-1963) 288 Epilogue: The Cross from Palenque 290 Archival Sources 290 End Notes 297 Illustration Credits 298 Bibliography 308 Index © 2017 The authors, Middle American Research Institute, and Precolumbia Mesoweb Press Translated from Det urolige blod – Biografi om Frans Blom © 2002 The authors and Høst & Søn / Rosinante & Co, Copenhagen All rights reserved Translated by Julie Nehammer Knub and the authors Produced and designed by Joel Skidmore and Chip Breitwieser Library of Congress Control Number 2017952616 ISBN 978-0-9859317-4-2 Printed in the United States of America 6 7 Acknowledgements This book could not have been written without the enthusiasm and generous help of the American documentary filmmaker Jaime Kibben, who Author Biographies was killed in a tragic car accident in 2003, just two months after its initial Tore Leifer (1964), MA in Musicology, Film, and Media from the University publication in Danish. -

1 FINAL REPORT Panel of Experts, New Orleans City Council Street

FINAL REPORT Panel of Experts, New Orleans City Council Street Renaming Commission Preamble How do we do justice to the centuries of history that have unfolded on these 350 square miles of land surrounding the Mississippi River? What is the relationship between this diverse history, its reflection in our city’s officially named spaces and places, and the values we strive to enact as a community? This report, prepared with the input of more than forty of the city’s leading scholars and writers, themselves drawing on more than a century of the most cutting-edge historical and cultural interpretation, offers no definitive answers to these questions. We have been guided throughout though by the conviction that asking these questions, developing a collaborative process, telling the multitudinous stories contained in this report, and reconsecrating some of the spaces in this city is an imperative as New Orleans enters its fourth century of existence as a city. The collective 111 suggestions for renaming streets and parks below makes no claim toward being a definitive history of the city. For every musical innovator like Jelly Roll Morton, Mahalia Jackson, or Mac Rebennack included there is a Bunk Johnson, Emma Jackson, Ernie K-Doe and countless others who have been left out. The four individuals included who fled the men who owned them as slaves near present-day Lakeview are but four of the thousands in this city’s history whose collective individual actions over centuries forced a reluctant nation to finally begin to live up to its highest ideals. The rolls of the First Louisiana Native Guard of the U.S. -

The Mexican Connection

The Mexican Connection The population of Southern Louisiana, and especially of New Orleans, has many deep and long-lasting connections with Mexico. These include not only family ties but cultural influences, such as cuisine, art, furniture and music, which have made their way back and forth across the Mexican-American border for centuries. Historical, as well as cultural connections, abound. Gálvez defeats the British at the Siege of Pensacola, 1781. Bernardo de Gálvez (1746 – 1786) was the fourth Spanish colonial governor of Louisiana, from 1777 to 1785, and remembered for his successes against the British during the American Revolution. He also endeared himself to the French Creole population of New Orleans by marrying in November 1777 Marie Félicité de Saint-Maxent d'Estrehan, the daughter of Gilbert Antoine de Saint-Maxent and recent widow of Jean-Baptiste d’Estréhan’s son. For his many achievements, Gálvez (for whom a major thoroughfare in New Orleans is named) was made a count in 1783 and soon after Viceroy of New Spain. This took him to Mexico, where he arrived in Vera Cruz on May 21, 1785, and made his formal entry into Mexico City that June. In Mexico City, Gálvez did many great things, such as ordering the installation of street lights and the paving of streets, as well as the construction of the cathedral towers. He also initiated the construction of Chapultepec Castle in 1785. When a famine and typhus epidemic struck the following year killing 300,000 people, Gálvez donated 12,000 pesos of his own inheritance and raised an additional 100,000 pesos to buy beans and maize for the populace. -

Arte Diseño Xicágo: Mexican Inspiration from the World's

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Mia Lopez, review of Arte Diseño Xicágo: Mexican Inspiration from the World’s Columbian Exposition to the Civil Rights Era, National Museum of Mexican Art, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https:// doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1679. Arte Diseño Xicágo: Mexican Inspiration from the World’s Columbian Exposition to the Civil Rights Era Curated by: Cesáreo Moreno Exhibition schedule: National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, March 23–August 19, 2018 Reviewed by: Mia Lopez, Assistant Curator, DePaul Art Museum Fig. 1. Errol Ortiz (b.1941), Astronaut Targets, 1965, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 60 in. Courtesy of Corbett vs. Dempsey. Photo by Tom Van Eynde Across Chicago museums and cultural institutions, 2018 has been a year to celebrate the city’s achievements in art and design. The Terra Foundation for American Art has partnered with Chicago cultural organizations on more than thirty exhibitions and one hundred events that look back at the artists, neighborhoods, moments, and developments that have shaped the city. Art Design Chicago encourages both cross-city exploration as well as celebration of the hyperlocal, with participants that encompass the Art Institute of Chicago in downtown, journalpanorama.org • [email protected] • ahaaonline.org Lopez, review of Arte Diseño Xicágo Page 2 the South Side Community Arts Center in Bronzeville, and Northwestern University in Evanston. In Pilsen, Arte Diseño Xicágo, presented by the National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) takes a closer look at the histories of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in Chicago. -

Caroline Wogan Durieux, the Works Progress Administration, and the U.S

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-14-2010 Works of Art, Arts for Work: Caroline Wogan Durieux, the Works Progress Administration, and the U.S. State Department Megan Franich University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Franich, Megan, "Works of Art, Arts for Work: Caroline Wogan Durieux, the Works Progress Administration, and the U.S. State Department" (2010). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1170. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1170 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Works of Art, Arts for Work: Caroline Wogan Durieux, the Works Progress Administration, and the U.S. State Department Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Megan Franich B.A. Gonzaga University, 2005 M.A. -

Game Changers Paula Burch-Celentano Head of the Class Taris Shenall Leads His Classmates in an Intro to Jazz Dance Exercise During the Last Day of Class in June

PUSH WOMEN AT GREEN HOMEGIRL AND PULL THE TOP OF APPLE Designer Becky Female student- THEIR GAME Environmentalist Vizard creates athletes strive Graduates make Lisa Jackson moves fancy pillows from THE MAGAZINE OF TULANE UNIVERSITY for excellence their mark to technology giant antique textiles TUSEPTEMBER 2016 lane Game Changers PAULA BURCH-CELENTANO HEAD OF THE CLASS Taris Shenall leads his classmates in an Intro to Jazz Dance exercise during the last day of class in June. The course, taught by associate professor of dance Beverly Trask, explores the legacy of jazz dance: from its roots in African and Carib- bean dance traditions to its assimilation into contemporary American dance culture. Shenall is a sophomore and a member of the Green Wave football team. Recruitment Back cover: The Molly Marine statue looks out over Canal Street in downtown New Orleans. Commis- sioned by the Marine Corps to recruit women during World War II, it is the first monument of a woman in a U.S. service uniform. It was created by sculp- tor Enrique Alferez in 1943. The inscription on the base of the stature reads: “Free a Marine to Fight.” (Photo by Paula Burch-Celentano) TULANE MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 2016 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Another high-achieving Tulane student who would make her predecessors proud is biomedical engineering major Anne Wolff. A Woman’s World Anne has traveled to Rwanda, where she by Mike Fitts assisted locals in fixing difficult-to- replace medical equipment and wrote a compelling case study on Throughout its history, Tulane University has been defined the gendered consequences of by women. -

Tom Lea Papers, MS 476, Must Be Obtained from the C

MS 476 Tom Lea papers Span Dates, 1875-2007 Bulk Dates, 1924-1995 136 feet 3 inches (linear) Processed by Laura Hollingsed, 2005 Donated by Sarah Lea in 2002. Citation: Tom Lea papers, 1875 – 2007, MS 476, C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department, The University of Texas at El Paso Library. C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department University of Texas at El Paso 2 Tom Lea Papers Table of contents Images Biography Selected Literary and Artistic Work Series Description Scope and Contents Note Provenance Statement Restrictions Literary Rights Statement Notes to Researchers List of Materials Removed Related Collections Container List Biography El Paso native artist and writer Tom Lea (Thomas Calloway Lea, III) was born on July 11, 1907 to Tom and Zola May Utt Lea. His father, the elder Tom Lea, was a prominent attorney, and served as mayor of El Paso, Texas from 1915-1917, during the tumultuous years of the Mexican Revolution. People and events during this period in the Southwest and on the United States-Mexico border greatly influenced Lea’s life and his art. Tom Lea and his younger brothers, Joe and Dick, attended El Paso public schools, where Tom displayed an early talent for art. After graduating from El Paso High School in 1924, he left home to attend the Chicago Art Institute. After two years of instruction, Lea quit art school in 1926 and began various residential and commercial art projects in the Chicago and Midwest areas. To supplement his income he worked part-time as an art teacher. In 1927, Lea became an assistant to Chicago muralist, John Norton.