Breaking the Caste Code in Uttar Pradesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

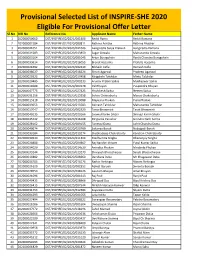

Provisional Selected List of INSPIRE-SHE 2020 Eligible For

Provisional Selected List of INSPIRE-SHE 2020 Eligible For Provisional Offer Letter Sl. -

Development of Regional Politics in India: a Study of Coalition of Political Partib in Uhar Pradesh

DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL POLITICS IN INDIA: A STUDY OF COALITION OF POLITICAL PARTIB IN UHAR PRADESH ABSTRACT THB8IS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fioctor of ^IHloKoplip IN POLITICAL SaENCE BY TABRBZ AbAM Un<l«r tht SupMvMon of PBOP. N. SUBSAHNANYAN DEPARTMENT Of POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALI6ARH (INDIA) The thesis "Development of Regional Politics in India : A Study of Coalition of Political Parties in Uttar Pradesh" is an attempt to analyse the multifarious dimensions, actions and interactions of the politics of regionalism in India and the coalition politics in Uttar Pradesh. The study in general tries to comprehend regional awareness and consciousness in its content and form in the Indian sub-continent, with a special study of coalition politics in UP., which of late has presented a picture of chaos, conflict and crise-cross, syndrome of democracy. Regionalism is a manifestation of socio-economic and cultural forces in a large setup. It is a psychic phenomenon where a particular part faces a psyche of relative deprivation. It also involves a quest for identity projecting one's own language, religion and culture. In the economic context, it is a search for an intermediate control system between the centre and the peripheries for gains in the national arena. The study begins with the analysis of conceptual aspect of regionalism in India. It also traces its historical roots and examine the role played by Indian National Congress. The phenomenon of regionalism is a pre-independence problem which has got many manifestation after independence. It is also asserted that regionalism is a complex amalgam of geo-cultural, economic, historical and psychic factors. -

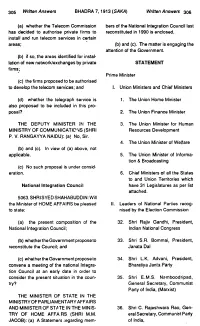

(A) Whether the Telecom Commission Has Decided to Authorise Private

305 Written Answers BHADRA 7.1913 (SAKA) Written Answers 306 (a) whether the Telecom Commission bers of the National Integration Council last has decided to authorise private firms to reconstituted in 1990 is enclosed. install and run telecom services in certain areas; (b) and (c). The matter is engaging the attention of the Government. (b) if so, the areas identified for instal- lation of new network/exchanges by private STATEMENT firms; Prime Minister (c) the firnis proposed to be authorised to develop the telecom services; and I. Union Ministers and Chief Ministers (d) whether the telegraph service is 1 . The Union Home Minister also proposed to be included in this pro- posal? 2. The Union Finance Minister THE DEPUTY MINISTER !N THE 3. The Union Minister for Human MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIC'>IS (SHRI Resources Development P. V. RANGAYYA NAIDU); (a) No. Sir. 4. The Unton Minister of Welfare (b) and (c). In view of (a) above, not applicable. 5. The Union Minister of Informa- tion & Broadcasting (c) No such proposal is under consid- eration. 6. Chief Ministers of all the States to and Union Territories which National Integration Council have 31 Legislatures as per list attached. 5063. SHRI SYED SHAHABUDDIN: Will the Minister of HOME AFFAIRS be pleased II. Leaders of National Parties recog- to state: nised by the Election Commission (a) the present composition of the 32. Shri Rajiv Gandhi, President, National Integration Council; Indian National Congress (b) whethertheGovernment propose to 33. Shri S.R. Bommai, President, reconstitute the Council; and Janata Dal (c) whether the Government propose to 34. -

Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science

A STUDY OF ELECTORAL PARTICIPATION OF BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY IN UTTAR PRADESH SINCE 1996 Thesis Submitted For the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science By Mohammad Amir Under The Supervision of DR. MOHAMMAD NASEEM KHAN DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) Department Of Political Science Telephone: Aligarh Muslim University Chairman: (0571) 2701720 AMU PABX : 2700916/27009-21 Aligarh - 202002 Chairman : 1561 Office :1560 FAX: 0571-2700528 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. Mohammad Amir, Research Scholar of the Department of Political Science, A.M.U. Aligarh has completed his thesis entitled, “A STUDY OF ELECTORAL PARTICIPATION OF BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY IN UTTAR PRADESH SINCE 1996”, under my supervision. This thesis has been submitted to the Department of Political Science, Aligarh Muslim University, in fulfillment of requirement for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. To the best of my knowledge, it is his original work and the matter presented in the thesis has not been submitted in part or full for any degree of this or any other university. DR. MOHAMMAD NASEEM KHAN Supervisor All the praises and thanks are to almighty Allah (The Only God and Lord of all), who always guides us to the right path and without whose blessings this work could not have been accomplished. Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to Late Prof. Syed Amin Ashraf who has been constant source of inspiration for me, whose blessings, Cooperation, love and unconditional support always helped me. May Allah give him peace. I really owe to Prof. -

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume 98

1. GIVE AND TAKE1 A Sindhi sufferer writes: At this critical time when thousands of our countrymen are leaving their ancestral homes and are pouring in from Sind, the Punjab and the N. W. F. P., I find that there is, in some sections of the Hindus, a provincial spirit. Those who are coming here suffered terribly and deserve all the warmth that the Hindus of the Indian Union can reasonably give. You have rightly called them dukhi,2 though they are commonly called sharanarthis. The problem is so great that no government can cope with it unless the people back the efforts with all their might. I am sorry to confess that some of the landlords have increased the rents of houses enormously and some are demanding pagri. May I request you to raise your voice against the provincial spirit and the pagri system specially at this time of terrible suffering? Though I sympathize with the writer, I cannot endorse his analysis. Nevertheless I am able to testify that there are rapacious landlords who are not ashamed to fatten themselves at the expense of the sufferers. But I know personally that there are others who, though they may not be able or willing to go as far as the writer or I may wish, do put themselves to inconvenience in order to lessen the suffering of the victims. The best way to lighten the burden is for the sufferers to learn how to profit by this unexpected blow. They should learn the art of humility which demands a rigorous self-searching rather than a search of others and consequent criticism, often harsh, oftener undeserved and only sometimes deserved. -

![5 F Viav]D <Zdy`C Arhr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8612/5-f-viav-d-zdy-c-arhr-3318612.webp)

5 F Viav]D <Zdy`C Arhr

/ , 4$ 1 & ' #& 5 #& 5 5 VRGR $"#(!#1')VCEBRS WWT!Pa!RT%&!$"#1$# *, -*./01 1-1-5 01234( %12*46 ' ; !*3)60*3) 2*603$ 7 )13:$3; 102: C)3! 232:)0!* $!*3)6$0 3$8$019$*:10;0) 0 :30) *) 2*:* 2)16*2 102*1:) 2710*18,7!1 ($)<=>**+ ?@ A& 0&' ' '23334 5 02 )0!102 ihar Chief Minister Nitish BKumar on Wednesday expelled two senior most leader-Prashant Kishor and Pavan Verma from the Janata dal (U) for accusing him of committing “ideological betrayal” by supporting the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and aligning with the BJP for the Delhi Assembly polls. Nitish took the extreme step after Kishor on Tuesday launched a vehement attack on him tweeting, “Nitish Kumar 4 ! 5 4 *7 + 0 what a fall for you to lie about how and why you made me join JDU!! Poor attempt on % " # your part to try and make my colour same as yours!” He was responding to Nitish’s claim that he inducted " Kishor on Amit Shah sugges- untebable for the JD(U) lead- being successful in his power loyalty to ideology”, he said. ministerial candidate in the tion. ership to justify how could one pursuits by compromising The election strategist had 2014 Lok Sabha polls. He was )0!102 friends of India prevailed over by India’s Supreme Court. Though the immediate of their senior leaders be man- `ideology’.Prashant Kishor a couple of days ago sought to also seen as a key force in seal- the friends of Pakistan in the Diplomatic sources said cause for the expulsion of aging the poll campign of offered Kumar his best wishes embarrass Sushil Modi by shar- ing Nitish’s alliance with the he European Parliament European Parliament on the vote on the resolution Kishor and Verma is seen as Mamata Banerjee. -

Fresh List 31/08/2021 Note

Fresh List 31/08/2021 Note:- 1. The administrative order 16.12.2013 regarding part head and tied up cases will continue in operation; 2. Priority hearing to those criminal appeals where the accused has undergone more than half the sentence in view of Section 436A Cr.P.C. and the accused is in jail; 3. Priority hearing to matters relating to murder, rape, dacoity and kidnapping; 4. Priority hearing to those cases wherein the proceedings of the trial court is stayed or record summoned; and 5. Priority hearing to those cases wherein mediation is successful. Fresh List 31-08-2021 AT 10:00 AM (Court No.1 ) HON'BLE JUSTICE J.J. MUNIR - (5187 - Single Bench ) e-Court Fresh ECOURT CASES. CIVIL REVISION 1. DF 1/2021 NEW OKHLA INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT SR. ADVOCATE AUTHORITY KAUSHALENDRA NATH SINGH MANAS BHARGAVA VS SURENDRA SINGH AND 4 OTHERS Category:REVISION, District Name:GAUTAM BUDDH NAGAR, TRANSFER APPLICATION (CIVIL) 2. DF 309/2021 NAMITA @ PAYAL HARSH VARDHAN GUPTA VS VIKAS AGRAWAL Category:TRANSFER APPLICATION U/S 24 CPC, District Name:BIJNOR, 3. 369/2021 MURATI DEVI ASHUTOSH KUMAR SINGH VS ARVIND SRIVASTAVA III SHANTI DEVI AND ANOTHER Category:TRANSFER APPLICATION U/S 24 CPC, District Name:GHAZIPUR, 31-08-2021 3/933 Court No.->1 Fresh List 31-08-2021 AT 10:00 AM (Court No.1 ) HON'BLE JUSTICE J.J. MUNIR - (5145 - Single Bench ) Fresh WRIT - A 4. 10804/2021 SHAILENDER KUMAR GUPTA VISHNU SWAROOP AND 2 OTHERS SRIVASTAVA VS SMT. PRAMILA DEVI AND ANOTHER Category:RENT CONTROL ACT,Subcategory:Miscellaneous, District Name:GORAKHPUR, MATTERS UNDER ARTICLE 227 5. -

Ram Madhav Book on Communal Violence Bill

COMMUNAL VIOLENCE BILL 2011 Threat to National Integration, Social Harmony and Constitutional Federalism RAM MADHAV JAGARANA PRAKASHAN BANGALORE Authored by : RAM MADHAV Director, India Foundation, New Delhi Member, Central Executive, RSS Published by : JAGARANA PRAKASHAN # 74, Rangarao Road Shankarapuram, Bangalore - 560 004 Ph : 080-26610081 www.samvada.org First Edition : 2011 Price : Rs. 10/- Printed at: Rashtrotthana Mudranalaya K.G. Nagar, Bangalore - 560 019 Ph : 080-26612730 Email : [email protected] 2 COMMUNAL VIOLENCE BILL 2011 Threat to National Integration, Social Harmony and Constitutional Federalism Ever since the UPA Government came to power in 2004 there started a cacophony about bringing a stricter law to prevent communal violence in the country. In its first term the UPA Government had, as its alliance partners, the Left parties as well as leaders like Lalu Prasad Yadav and Ram Vilas Paswan etc. It may be worthwhile to recall that it were these very people who had launched a massive campaign of disinformation about the then existing anti-terrorism law called the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA). They finally succeeded in getting the POTA repealed on the specious ground that it was being used to harass innocent Muslims. Any amount of statistical data contrary to their false claims against POTA wouldn’t convince them because the main objective behind the campaign against the POTA was to play the same old game of vote-banks. Incidentally after the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers in New York many countries in the world including America have introduced fresh stringent laws against terror while India became the only country to repeal the existing laws thus leaving the security agencies without any instrument to tackle the huge challenge of terror. -

Lok Sabha Debates for the Eighth Lot Sdbha

(LJKWK6HULHV9RO,1R 7XHVGD\-DQXDU\ 0DJKD 6DND /2.6$%+$'(%$7(6 (QJOLVK9HUVLRQ )LUVW6HVVLRQ (LJKWK/RN6DEKD /2.6$%+$6(&5(7$5,$7 1(:'(/+, 3ULFH5V PREFACE This is the first vo1ume of the Lok Sabha Debates for the Eighth Lot Sdbha. Upto the end of the Seventh Lok Sabha, two versions of Lok Sabha Debates were brought out, viz., (i) Original VersIon containing the procee- dings of the House in the languages in which they took place except that in the case of speeches made in regional languages, their English! Hindi translation was included and the Urdu Speecbe:; were put in Devnagri script and their Persian script was also given within brackets, and (ii) Hindi Version containing the Hindi proceedings, Urdu proceedings in Devnagri script and Hindi translation of English proceedings and also of Speeches made in regional langu~:ges. 2. \Vith effect fr Jrn the First Session of Eighth Lol Sabha, in pursu- ance of a decision of the General Purpo~es Committee of Lok Sabha: two versions of Lok Sabha Debates are being brought out, viz., (i) English Version containing Lok Sabha proceedings in English and English translation of the proceedings which take place in Hindi or any regional language. aDd (ii) Hindi Version in its present form except that Urdu speeches ale hein, put in Devnagri script and their Persi'-ln Script is also being given within br"h: kets. 3. In addit;on. Original Version of the Lok Sabha proceedings is "'" being prepared nnd kept in Parliament Library suitably bound for purposes of record and reference only. ' 4. -

The Pioneer > Online Editio

The Pioneer > Online Edition : LUCKNOW >> UP Legislative Council ... http://www.dailypioneer.com/230178/UP-Legislative-Council-to-get-its... LUCKNOW | Tuesday, January 19, 2010 | Print | Close UP Legislative Council to get its first dalit Chairman Pioneer News Service | Lucknow After an illustrious career of 124 year the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Council also known as Vidhan Parishad is all set to get its first dalit Chairman in form of former minister Kamla Kant Gautam who had been already appointed as protem Chairman. After the splendid performance in the recently concluded Legislative Council elections in which the ruling BSP wrested 34 out of 36 seats it also obtained the majority in 100 member House with 56 BSP members in it. The present incumbent and SP member Chaudhri Sukhram Singh Yadav ceased to exist as Chairman as his tenure came to an end on January 15. Kamla Kant Gautam who served as the Finance Minister when Mayawati Government was formed on May 13, 2007 has been appointed as protem Chairman and it is believed once House sets into he will be formally elected as its Chairman. The UP Legislative Council which came into being in 1887 has got its first dalit Leader of the House in 1972 in form of Baldev Singh Arya. The credit of becoming the first dalit Leader of the Opposition in the Vidhan Parishad went to Maharni Dohrey of the Congress who occupied the post in 1994. The UP Legislative had several distinguished personalities as its member including the first Prime Minister of Pakistan Liyaqat Ali Khan who served the august House between 1921 and 1935. -

Lok Sabha Debates

Seventh Serlel, Vol., V No. 17 Wednesday, July 2, 1980 Asadha 11, 1902 (s.ta) LOK SABHA DEBATES Third Session (Seventh Lok Sabha) (Yol.V contains Nos. 11 -2 0) LOIC SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DEJ,m Prb ' Ba. ,.oo (ORIGINAL ENGLISH PI.OCEBDINGS INCLUDED IN ENGLISH VBRSION AND ORIGINAL HINDI PltOCBBDINGS INCLUDED IN HINDI VBltSION WILL DB TB.BATID AS AUTBOlUTATIVE AND NOT THE TltANSLATIONTHEREOF.J CONTBNTS No. 17, Wednesday July 2, I98o/A.sadha II, 1902 (Saka) I. COLUMNS Oral Answers to Questions: *Starred Questions Nos. 345, 348, 349, 35 1 and 353 to 356 I-gO Written Answers to Questions: Starred Questions Nos. 346, 352 and 358 to 364 • Unc;tarced Questions Nos 2618 to 2648, 2650 to 2700, 2702 to 27 1 7 and 2719 and 2755 . 38- 186 ~Ies~age from Rajya Sabha • • C ",lling Attention to Matter of Urgent Public Importance- Reported Chinese offer to settle the border problem on the basis of present line 01 actual control. • • • • • 189-202 Shri Ram Vilas Pac;wan 189, 19 1-94 Shri P. V. Narasimha Rao 189-91 Shri Ghulam Rasool Kochak . 194-97 Sh~i Bheekha bhai . 198-99 Dr. Subramaniam Swamy 199-202 Committee on Private Members" Bills and Resolutions- Third R~p()rt 203 Statement re Newsprint allocation Policy, 1980-81- Shri Vac;ant Sathe . 20 3-206 Mdtter3 under rule 377- (i) Rcp'Jrt<:"d arrest of a Journalist by Police in ]amml1- Shri H l.rikesh Bahadur 206-20 Shri V c:l.sant Sat.he (ii) Reported withholding ofpensiol1 to freedom fighters by U.P. -

I Riffihl UI 11W 1111111111111 Ft ' Under the Supervision of T9073 Dr

RELIGION AS A FACTOR: A STUDY OF PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN U.P. SINCE 1984 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF ;Doctor of 3pbilozopbp IN POLITICAL SCIENCE By LUBNA MUSTAFA I Riffihl UI 11W 1111111111111 ft ' Under the supervision of T9073 Dr. ,MOHD. ABID (Reader in Political Science) DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH October 200 1~ ~~ 7 }~WVHMU~D ~w/~ --r ~ --- ---_---'__-._-------_ ` [ ~ II1UII DI Ill IIll lull ThI | ' | T9073 ~ . ' ---_'| ~ e 4p*uM TELEPHONES : Chairman (0571)700 2701720 ARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ° AMU PABX 70091.61740920-21-22 ''ARIL - 202 002 Chairman: 1561 Office :1560 FAX : 0571-700528 Dated ...................................... This is to certify that Ms. Lubna Mustafa has revised her Ph.D. thesis on "Religion as a Factor: A Study of Parliamentary Elections in U.P. since 1984" as per instructions of the examiner. The thesis, in my opinion, is suitable for re-submission for the award of Ph.D. degree. •. (Mohd. Abid) Reader -- SuprJiO Dept of P.c ::eF1{;9 A.tiILU.1 Aki uch /4 a CONTENTS Preface i-iv Abbreviations v-vii List of Tables viii Chapter-1 1-56 Introduction- Religion and Politics in India: A Historical Perspective (a) The Interface between Religion and Politics 1 (b) The Role of Religion in Indian Politics 18 (c) The Emergence of Hindu Nationalism 38 (d) The Genesis of Muslim Politics 46 Chapter-II The Quest for Power: Caste and Communal Mobilization 57-90 (a) The Nature of Indian Politics alter Independence 57 (b) The Caste Factor: Mandalization of Indian Politics. 64 (c) The Religious Factor: Advani's 'Rath Yatra and Beyond 75 Chapter-Ill The Electoral Politics in Uttar Pradesh.