National Integrity System Assessment Vanuatu 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal Officiel Official Gazette

-r----./<i;'J> ~/ REpUBIJQUE REPUBl.IC Of Of VANUATU VANUATU JOURNAL OFFICIEL OFFICIAL GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY GAZEITE 9 DECEMBRE 1991 9 DECEMBER 1991 NLMERO SPECIAL SONT PUBLIES LES TElITES SUIVANI'S NOTIFICATION OF PUBLICATION RESULTATS DES ELECTIONS AU RESULTS OF THE ELECfIONS TO PARLEMENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE DE PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU TENUES LE 2· DECEMBRE VANUATU HEW ON DECEMBER 2, 1991. 1991. SCM1AIRE PAGE CONTENTS PAGE LEGAL NOTICE 1 \ -, " REPUBLIC OF VANUATU THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION DECLARATION UNDER THE REPRESENTATION OF nn;; PEOPLE ACT (CHAPTER 146) - SCHEDULE 5 RULE 21 IN EXERCISE of the power contained in Rule 21(1) of schedule 5 to Representation of People Act CAP 146, and following General Elections to Parliament of Rppubl ic of Vanuatu held on December 2nd, 1991, THE ELECTORAl. COMMISSION HEREBY ANNOUNCES the number of votes cast for each candidate in each constituency : 1. BANKS AND TORRES CONSTITUENCY - 2 SEATS (6 CANDIDATES) Registered voters: 3487 Votes cast 2673 Turn out 76.65% Void votes 27 Valid votes cast 2646 CANDIDATES ---------AFFILIATION VOTES CECIL SINKER NASIONAL UNAETED PATI (NUP) 837 DEREK I.uum VANUA NUP 707 ELDAT ESUVA FOX UNION OF MODERATE PATI (IJMP) 514 CHARLES GODDEN MELANESIAN PROGRESSIVE PAT I (MPP) 278 BEN REYNOLD TAN UNION (Til) 224 GEORGE AUGUSTUS WOREK VANUAAKU PATI (VP) 86 2646 2. SANTO/MALO/AORE CONSTITUENCY 6 SEATS (18 CANDIDATES) Registered voters: 10043 I---------Votes cast-------- --. 8016 Turn out 79.81% Void votes 71 Valid votes cast 7945 ..... 12 2 CANDIDATES AFFILIATION VOTES VOHOR SERGE liMP 1000 SELA MOUSA VP 936 PISUVOKE RAVUTIA ALBERT FMP 8114 WEI-ES TIMOTHY UMP 733 VUROBARI\VlI MOLIENO UMP 523 STEVEN FRANKY NAG 487 HARRY KI\RAERU liMP 440 TALPER NIAL VP 399 JERRY ISAIAH NAG 393 SARKI ROBERT VP 392 THOMAS RUBEN SERU MPP 372 PIERRE LEON AISOSO NAG 284 B. -

Ninth Legislature of Parliament

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU NINTH LEGISLATURE OF PARLIAMENT FOURTH EXTRA ORDINARY SESSION OF 2009 MONDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2009 SPEAKER : The Hon. Maxime CARLOT Korman, Member for Port Vila PRESENT : 36 Members ABSENT : Hon. Philip BOEDORO, Member for Maewo Hon. James BULE, Member for Ambae Hon. Moana CARCASSES, Member for Port Vila Hon. Louis ETAP, Member for Tanna Hon. Iauko H. IARIS, Member for Tanna Hon. Joshua KALSAKAU, Member for Efate Hon. Sato KILMAN, Member for Malekula Hon. Solomon LORIN, Member for Santo Hon. Dominique MORIN, Member for Luganville Hon. Edward NATAPEI, Member for Port Vila Hon. Thomas I. SAWON, Member for Banks/Torres Hon. Ioane S. OMAWA, Member for Epi Hon. George A. WELLS, Member for Luganville LATE : Hon. Jean Ravou KOLOMULE, Member for Santo Hon. Paul TELUKLUK, Member for Malekula 1. The sitting commenced at 8.50a.m. 2. The Hon. Speaker CARLOT Korman stated that according to Article 21(4) of the Constitution that two thirds of the Members should be present at the first sitting in any session of Parliament and as there was a quorum consisting of 36 Members, it rendered the sitting to be legally and constitutionally constituted to proceed with the Fourth Extra Ordinary session of 2009. 1 3. The Hon. Ps Ton KEN, Member for Malekula said the prayer. 4. The Hon. Speaker read the agenda. 5. The Hon. Ham LINI, Leader of Opposition and Member for Pentecost raised a point of order then asked if the sitting could be adjourned until 8.30a.m the next day to allow sufficient time for Members who have just arrived from the islands (constituencies) to read their Bills. -

Republic of Vanuatu Parliament Repu0lique De

REPUBLIC OF VANUATU REPU0LIQUE DE VANUATU PARLIAMENT PARLEMENT THIRD PARLIAMENT FIRST ORDINARY SESSION 2ND MEETING 22ND MAY - 25TH MAY 1989 TROISIEME LEGISLATURE DU PARLEMENT PREMIERE SESSION ORDINAIRE DEUXIEME ETAPE SESSIONNELLE 22 MAI - 25 MAI 19B9 SUMMARISED PROCEEDINGS PRDCES VERBAL CERTIFICATION Ths Minutes of Proceedings which appear in the following book have been established by the Clerk of Parliament and have been amended and confirmed by Parliament in accordance with the provisions of Article 18 of the Standing Orders of Parliament. Onneyn M. TAHI Lino 8ULEKULI dit SACSAC Speaker of Parliament. ClBrk of Parliament, AUTHENTIFIACTION Les Proc&s-verbaux qui figurant dans Is present recuBil ont ete etablia par la Secretaire Gdneral du Parlement et conformemsnt aux dispositions ds 1*Article 18 du R&glement Intdrieur, ils ont ete corrigds et confirmds par le Parlament. Onneyn l*l» TAHI Lino BULEKULI dit SACSAC President Secretaire Gdndral du ParlemBnt. du Parlement, PARLIAMENT Of THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU THIRD PARLIAMENT FIRST ORDINARY SESSION 2ND MEETING 22ND MAY - 25TH MAY 1909 ABBIL 3, Iolu, MP for Tanna, BAET George, MP for Benke / Torres, BOE Roger Derry, MP for Maewo, BOULEKONE Vincent, MP for Pentecost, BULEWAK Gaetano, MP for Pentecoat, ENNIS Simeon, MP for Malekuia, HOPA T. Dock, MP for Ambrym, IAMIAHAM Daniel, MP for Tanna, IAUKO Deck, MP for Tanna, IOUIDU Henry, MP for Tanna, DIMMY floanikam, MP for Tanna, DACOBE Joseph, MP for Port-Vila, KALPOKAS Donald, MP for Efate, KARIE D. Robert, MP for Tongoa / Shepherds, KATH Daniel, MP for Santo, Malo / Aore, KOTA Gideon, MP for Tanna, LINI Hilda, MP for Port-Vila, LINI Walter H«, MP for Pentecoat, MAHIT William, MP for Paama, MATASKELEKELE Kalkot, MP for .Port-Vila, METO Dimmy Chilia, MP for Efete, MOLISA Sela, MP for Santo, Malo / Aore, NATAPEI E, Nipake, MP for Other Southern Islands, NATO Daniel, MP for Malekuia, NIAL 3, Kalo, MP for Luganville, QUALAO C. -

Pol I T Ical Reviews • Melanesia 467 References Vanuatu

pol i t ical reviews • melanesia 467 References controlling prisoners. Issues of eco- nomic policy also created challenges Fraenkel, Jonathan, Anthony Reagan, and with Vanuatu’s financial services David Hegarty. 2008. The Dangers of sector coming under increasing pres- Political Party Strengthening Legislation in Solomon Islands. State Society and Society sure, the rising cost of living being felt in Melanesia Working Paper (ssgm) quite strongly, and a proposed increase 2008/2. Canberra: ssgm, The Australian to employment conditions creating National University. uncertainty within the private sector. Ham Lini’s National United Party ISN, Island Sun News. Daily newspaper, Honiara. (nup)–led coalition had taken over in December 2004, following a success- mehrd, Ministry of Education and ful vote of no confidence against the Human Resources Development. 2009. government coalition led by Serge Semi-annual Report, January–July. Vohor’s Union of Moderate Parties mehrd: Honiara. (ump), which had been elected only NEN, National Express News. Tri-weekly five months earlier. Although several newspaper, Honiara. reshuffles took place in the intervening sibc, Solomon Islands Broadcasting years, Lini’s ability to survive to the Corporation. Daily Internet news service, end of Parliament’s four-year term was Honiara. http://www.sibconline.com remarkable. The previous decade had SSN, Solomon Star News. Daily news - seen regular votes of no confidence paper, Honiara. Online at and numerous threats of such votes http://solomonstarnews.com / leading to nine different coalition sto, Solomon Times Online. Daily governments and two snap elections. Internet news service, Honiara. Lini was able to stay in power mainly http://www.solomontimes.com because he refused to take action (ie, hold accountable politicians who were members of the coalition accused of mismanagement, corruption, or misbehavior) or make decisions that Vanuatu could jeopardize the coalition. -

Report of the Fourth Ministers' Meeting

FAO Sub-Regional Office for the Pacific Islands ______________________________________________________ Report of the Fourth ______________________________________________________________________________________ MEETING OF SOUTH WEST PACIFIC MINISTERS FOR AGRICULTURE Port Vila, Vanuatu, 23-24 July 2001 FAO Sub-Regional Office for the Pacific Islands ______________________________________________________ Heads of Delegations and the Director-General of FAO at the Fourth Meeting of the South West Pacific Ministers for Agriculture Back row (left to right): Hon. Tuisugaletaua S Aveau (Samoa), Mr. Samisoni Ulitu (Fiji), Hon. Matt Robson (New Zealand), HE Perry Head (Australia), Hon. Willie Posen (Vanuatu), Hon. John Silk (Marshall Islands), Hon. Moon Pin Kwan (Solomon Islands), Hon. Emile Schutz (Kiribati) Front row (left to right): Hon. Young Vivian (Niue Deputy Prime Minister), Rt. Hon. Edward Natapei (Vanuatu Prime Minister), Hon. Donald Kalpokas (Vanuatu Acting President), Jacques Diouf (Director- General of FAO), HRH Prince „Ulukalala Lavaka Ata (Tonga Prime Minister) FAO Sub-Regional Office for the Pacific Islands ______________________________________________________ Report of the Fourth MEETING OF SOUTH WEST PACIFIC MINISTERS FOR AGRICULTURE Port Vila, Vanuatu, 23-24 July 2001 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS SUB-REGIONAL OFFICE FOR THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Apia, Samoa, 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. OFFICIAL OPENING 2. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA 3. WORLD FOOD SUMMIT: FIVE YEARS LATER 4. FAO ACTIVITIES IN THE PACIFIC 5. FOOD SECURITY IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC: i AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY POLICY IN THE PACIFIC: FIVE YEARS AFTER THE WORLD FOOD SUMMIT ii RESPONSIBLE FISHERIES AND FOOD SECURITY iii FOOD AND NUTRITION CHALLENGES iv PLANT PROTECTION AND BIOSECURITY IN FOOD SECURITY v SMALL-FARMERS‟ CONTRIBUTION TO NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY vi ENHANCING FOOD SECURITY THROUGH FORESTRY 6. -

Official Journal of the European Union C 391/1

Official Journal C 391 of the European Union Volume 58 English edition Information and Notices 24 November 2015 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES The 29th session took place in Suva (Fiji) from 15 to 17 June 2015. 2015/C 391/01 Joint Parliamentary Assembly of the Partnership Agreement concluded between the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific group of states, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part — Minutes of the sitting of monday, 15 june 2015 . 1 2015/C 391/02 Joint Parliamentary Assembly of the Partnership Agreement concluded between the Members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part — Minutes of the sitting of Tuesday, 16 June 2015 . 6 2015/C 391/03 Joint Parliamentary Assembly of the Partnership Agreement concluded between the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part — Minutes of the sitting of Wednesday, 17 June 2015 . 11 EN KEYS TO SYMBOLS USED * Consultation procedure *** Consent procedure ***I Ordinary legislative procedure: first reading ***II Ordinary legislative procedure: second reading ***III Ordinary legislative procedure: third reading (The type of procedure is determined by the legal basis proposed in the draft act.) ABBREVIATIONS USED FOR PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AFET Committee on Foreign Affairs DEVE Committee on -

Vanuatu National Energy Road Map 2013-2020

Vanuatu National Energy Road Map 2013-2020 _________________________________________ March 2013 Acronyms and Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank AusAID Australian Agency for International Development CIF Climate Investment Funds DOE Department of Energy FAESP Framework for Action on Energy Security in the Pacific GHG Greenhouse Gas GoV Government of Vanuatu GPOBA Global Partnership for Output Based Aid HDI Human Development Index LED Light Emitting Diode LPG Liquefied Petroleum Gas LV Low Voltage MEPS Minimum Energy Performance Standards MDGs Millennium Development Goals MIPU Ministry of Infrastructure and Public Utilities MV Medium Voltage OBA Output Based Aid PALS Pacific Appliance Labeling and Standards PIES Public Institutions Electrification Scheme PPAs Power Purchase Agreements PPC Pacific Petroleum Company PPPs Public Private Partnerships PV Photovoltaic RLSS Rural Lighting Subsidy Scheme SREP Scaling Up Renewable Energy Program in Low Income Countries SWAp Sector Wide Approach SWER Single Wire Earth Return UNELCO Union Electrique du Vanuatu Limited URA Utilities Regulatory Authority VERD Vanuatu Energy for Rural Development VISIP Vanuatu Infrastructure Strategic Investment Plan VUI Vanuatu Utilities & Infrastructure Limited Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................ iv Vanuatu National Energy Road Map ...................................................................................................... -

Report of the Parliamentary Delegation to Vanuatu and New Zealand by the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Co

Chapter 2 Vanuatu Country brief1 2.1 Vanuatu is an archipelagic nation of 83 islands, extending over 1,000 kilometres in a north-south direction between the equator and the tropic of Capricorn. Vanuatu has a small, dispersed, predominantly rural and culturally diverse population of approximately 250,000 people. Around 70 per cent live in rural areas on 65 of the 83 islands. Formerly known as the New Hebrides, Vanuatu was governed jointly by British and French administrations, in an arrangement known as the Condominium, before attaining independence on 30 July 1980. The country has six provinces (Torba, Sanma, Penama, Malampa, Shefa and Tafea) with limited administrative authority. Political system 2.2 Vanuatu has a unicameral 52-member parliament, elected to a four-year term. The President of the Republic is elected for a five-year term through secret ballot by an electoral college comprising the members of parliament and the presidents of the six provincial governments. The current President, Iolu Johnson Abbil, was elected in September 2009. The Prime Minister is elected by parliament from among its members by secret ballot. 2.3 Vanuatu is the only Pacific country with multi-member electorates. The proliferation of political parties is seen, by some, as one reason for persistent political instability. Until about 1991 the main political divide in Vanuatu was between Anglophones and Francophones, respectively represented by the Vanua’aku Pati (VP) and United Moderates Party (UMP). During the last decade, parties have been splintering over policy and, more often, personality differences, in a manner more typical of other Melanesian countries like Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. -

View Profile

Vanuatu Santo) rising to over 1,800 metres. Fresh has the fastest-growing population, as people water is plentiful. migrate to the capital; growth 2.4 per cent p.a. 1990–2013; birth rate 27 per 1,000 Climate: Oceanic tropical, with south-east people (43 in 1970); life expectancy 72 years trade winds running May–October. The (53 in 1970). period November–April is humid, with moderate rainfall. Cyclones may occur Most of the population is Melanesian, known November–April. as ni-Vanuatu (98.5 per cent in the 1999 census), the rest of mixed Micronesian, Environment: The most significant Polynesian and European descent. environmental issues are that a majority of the population does not have access to a safe Language: The national language is Bislama; and reliable supply of water (although it is English and French are widely spoken and improving), and deforestation. also official languages. There are more than 100 Melanesian languages and dialects. Vegetation: The rocky islands are thickly forested, with narrow coastal plains where Religion: Mainly Christians (Presbyterians 28 cultivation is possible. Forest covers 36 per per cent, Anglicans 15 per cent, Seventh Day cent of the land area and there was no Adventists 13 per cent and Roman Catholics significant loss of forest cover during 12 per cent; 2009 census). 1990–2012. Health: Public spending on health was three Wildlife: Vanuatu is home to 11 species of per cent of GDP in 2012. The major hospitals bat, including white flying-fox. It is also the are in Port Vila and Luganville, with health centres and dispensaries throughout the easternmost habitation of dugongs, also country. -

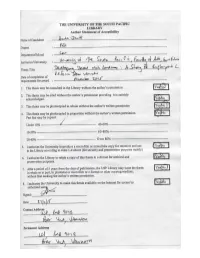

Title and Declaration

DEVELOPING DECENT WORK CONDITIONS: A STUDY OF EMPLOYMENT LAW REFORM FROM VANUATU by Anita Jowitt A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © 2015 by Anita Jowitt, School of Law The University of the South Pacific November 2015 DECLARATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my supervisor Miranda Forsyth. Thank you to people who took the time to comment on drafts, especially Howard Van Trease and Ted Hill. A number of people helped to make sure this was completed. Thank you to Robert Early, Howard Van Trease, John Lynch, Kenneth Chambers and Tess Newton Cain. This thesis was initially conceived following a conversation with the then Director of the Suva Office of the International Labour Organisation, Werner Blenk in 2009. It had been almost entirely written by January 2012, and was initially submitted in December 2012. Since the bulk of the work was completed I have had the privilege of using my academic work practically as a member of the Vanuatu Tripartite Labour Advisory Council. I have the greatest respect for all the people who have worked, and continue to work practically on employment law reforms in Vanuatu, including colleagues on the Vanuatu Tripartite Labour Advisory Council, International Labour Organisation advisors, members of the Vanuatu Chamber of Commerce and Industry and trade union representatives. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to take work done to meet academic requirements and use parts of it in practice, hopefully for the benefit of all. i ABSTRACT In November 2008 the Vanuatu parliament passed a Bill to amend the Employment Act [Cap 160] (the 2008 reform), which significantly increased benefits for employees. -

Vanuatu Cocoa Growers' Association

Lotusnotes The Vanuatu Cocoa Growers’ Associa- tion: Inclusive Trade in Rural Smallholder Agriculture Chris Geurtsen Trade and Investment Working Paper Series NO. 03/13| NOVEMBER 2013 ESCAP is the regional development arm of the United Nations and serves as the main economic and social development centre for the United Nations in Asia and the Pacific. Its mandate is to foster cooperation between its 53 members and 9 associate members. ESCAP provides the strategic link between global and country-level pro- grammes and issues. It supports Governments of the region in consolidating regional positions and advocates regional approaches to meeting the region’s unique and so- cio-economic challenges in a globalizing world. The ESCAP office is located in Bangkok, Thailand. Please visit our website at www.unescap.org for further infor- mation. Disclaimer: TID Working Papers should not be reported as representing the viewsof the United Nations. The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the au- thor(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations. Working Pa- pers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit com- ments for further debate. They are issued without formal editing. The designation employed and the presentation of the material in the Working Paper do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Na- tions concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authori- ties, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundariesThe United Nations bears no responsibility for the availability or functioning of URLs. -

Information Technology and Computer Science Education at St. Patrick's College in the Republic of Vanuatu

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports 2016 INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND COMPUTER SCIENCE EDUCATION AT ST. PATRICK’S COLLEGE IN THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU Timothy R. Ward Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Copyright 2016 Timothy R. Ward Recommended Citation Ward, Timothy R., "INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND COMPUTER SCIENCE EDUCATION AT ST. PATRICK’S COLLEGE IN THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU", Open Access Master's Report, Michigan Technological University, 2016. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etdr/221 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etdr INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND COMPUTER SCIENCE EDUCATION AT ST. PATRICK’S COLLEGE IN THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU By Timothy R. Ward A REPORT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In Computer Science MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Timothy R. Ward This report has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Computer Science. Department of Computer Science Report Advisor: Dr. Linda Ott Committee Member: Dr. Jean Mayo Committee Member: Dr. Charles Wallace Department Chair: Dr. Min Song Long pipol blong Vanuatu Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... iv Preface ................................................................................................................................