RRTA 165 (15 March 2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ninth Legislature of Parliament

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU NINTH LEGISLATURE OF PARLIAMENT FOURTH EXTRA ORDINARY SESSION OF 2009 MONDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2009 SPEAKER : The Hon. Maxime CARLOT Korman, Member for Port Vila PRESENT : 36 Members ABSENT : Hon. Philip BOEDORO, Member for Maewo Hon. James BULE, Member for Ambae Hon. Moana CARCASSES, Member for Port Vila Hon. Louis ETAP, Member for Tanna Hon. Iauko H. IARIS, Member for Tanna Hon. Joshua KALSAKAU, Member for Efate Hon. Sato KILMAN, Member for Malekula Hon. Solomon LORIN, Member for Santo Hon. Dominique MORIN, Member for Luganville Hon. Edward NATAPEI, Member for Port Vila Hon. Thomas I. SAWON, Member for Banks/Torres Hon. Ioane S. OMAWA, Member for Epi Hon. George A. WELLS, Member for Luganville LATE : Hon. Jean Ravou KOLOMULE, Member for Santo Hon. Paul TELUKLUK, Member for Malekula 1. The sitting commenced at 8.50a.m. 2. The Hon. Speaker CARLOT Korman stated that according to Article 21(4) of the Constitution that two thirds of the Members should be present at the first sitting in any session of Parliament and as there was a quorum consisting of 36 Members, it rendered the sitting to be legally and constitutionally constituted to proceed with the Fourth Extra Ordinary session of 2009. 1 3. The Hon. Ps Ton KEN, Member for Malekula said the prayer. 4. The Hon. Speaker read the agenda. 5. The Hon. Ham LINI, Leader of Opposition and Member for Pentecost raised a point of order then asked if the sitting could be adjourned until 8.30a.m the next day to allow sufficient time for Members who have just arrived from the islands (constituencies) to read their Bills. -

Report of the Fourth Ministers' Meeting

FAO Sub-Regional Office for the Pacific Islands ______________________________________________________ Report of the Fourth ______________________________________________________________________________________ MEETING OF SOUTH WEST PACIFIC MINISTERS FOR AGRICULTURE Port Vila, Vanuatu, 23-24 July 2001 FAO Sub-Regional Office for the Pacific Islands ______________________________________________________ Heads of Delegations and the Director-General of FAO at the Fourth Meeting of the South West Pacific Ministers for Agriculture Back row (left to right): Hon. Tuisugaletaua S Aveau (Samoa), Mr. Samisoni Ulitu (Fiji), Hon. Matt Robson (New Zealand), HE Perry Head (Australia), Hon. Willie Posen (Vanuatu), Hon. John Silk (Marshall Islands), Hon. Moon Pin Kwan (Solomon Islands), Hon. Emile Schutz (Kiribati) Front row (left to right): Hon. Young Vivian (Niue Deputy Prime Minister), Rt. Hon. Edward Natapei (Vanuatu Prime Minister), Hon. Donald Kalpokas (Vanuatu Acting President), Jacques Diouf (Director- General of FAO), HRH Prince „Ulukalala Lavaka Ata (Tonga Prime Minister) FAO Sub-Regional Office for the Pacific Islands ______________________________________________________ Report of the Fourth MEETING OF SOUTH WEST PACIFIC MINISTERS FOR AGRICULTURE Port Vila, Vanuatu, 23-24 July 2001 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS SUB-REGIONAL OFFICE FOR THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Apia, Samoa, 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. OFFICIAL OPENING 2. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA 3. WORLD FOOD SUMMIT: FIVE YEARS LATER 4. FAO ACTIVITIES IN THE PACIFIC 5. FOOD SECURITY IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC: i AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY POLICY IN THE PACIFIC: FIVE YEARS AFTER THE WORLD FOOD SUMMIT ii RESPONSIBLE FISHERIES AND FOOD SECURITY iii FOOD AND NUTRITION CHALLENGES iv PLANT PROTECTION AND BIOSECURITY IN FOOD SECURITY v SMALL-FARMERS‟ CONTRIBUTION TO NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY vi ENHANCING FOOD SECURITY THROUGH FORESTRY 6. -

Report of the Parliamentary Delegation to Vanuatu and New Zealand by the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Co

Chapter 2 Vanuatu Country brief1 2.1 Vanuatu is an archipelagic nation of 83 islands, extending over 1,000 kilometres in a north-south direction between the equator and the tropic of Capricorn. Vanuatu has a small, dispersed, predominantly rural and culturally diverse population of approximately 250,000 people. Around 70 per cent live in rural areas on 65 of the 83 islands. Formerly known as the New Hebrides, Vanuatu was governed jointly by British and French administrations, in an arrangement known as the Condominium, before attaining independence on 30 July 1980. The country has six provinces (Torba, Sanma, Penama, Malampa, Shefa and Tafea) with limited administrative authority. Political system 2.2 Vanuatu has a unicameral 52-member parliament, elected to a four-year term. The President of the Republic is elected for a five-year term through secret ballot by an electoral college comprising the members of parliament and the presidents of the six provincial governments. The current President, Iolu Johnson Abbil, was elected in September 2009. The Prime Minister is elected by parliament from among its members by secret ballot. 2.3 Vanuatu is the only Pacific country with multi-member electorates. The proliferation of political parties is seen, by some, as one reason for persistent political instability. Until about 1991 the main political divide in Vanuatu was between Anglophones and Francophones, respectively represented by the Vanua’aku Pati (VP) and United Moderates Party (UMP). During the last decade, parties have been splintering over policy and, more often, personality differences, in a manner more typical of other Melanesian countries like Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands. -

View Profile

Vanuatu Santo) rising to over 1,800 metres. Fresh has the fastest-growing population, as people water is plentiful. migrate to the capital; growth 2.4 per cent p.a. 1990–2013; birth rate 27 per 1,000 Climate: Oceanic tropical, with south-east people (43 in 1970); life expectancy 72 years trade winds running May–October. The (53 in 1970). period November–April is humid, with moderate rainfall. Cyclones may occur Most of the population is Melanesian, known November–April. as ni-Vanuatu (98.5 per cent in the 1999 census), the rest of mixed Micronesian, Environment: The most significant Polynesian and European descent. environmental issues are that a majority of the population does not have access to a safe Language: The national language is Bislama; and reliable supply of water (although it is English and French are widely spoken and improving), and deforestation. also official languages. There are more than 100 Melanesian languages and dialects. Vegetation: The rocky islands are thickly forested, with narrow coastal plains where Religion: Mainly Christians (Presbyterians 28 cultivation is possible. Forest covers 36 per per cent, Anglicans 15 per cent, Seventh Day cent of the land area and there was no Adventists 13 per cent and Roman Catholics significant loss of forest cover during 12 per cent; 2009 census). 1990–2012. Health: Public spending on health was three Wildlife: Vanuatu is home to 11 species of per cent of GDP in 2012. The major hospitals bat, including white flying-fox. It is also the are in Port Vila and Luganville, with health centres and dispensaries throughout the easternmost habitation of dugongs, also country. -

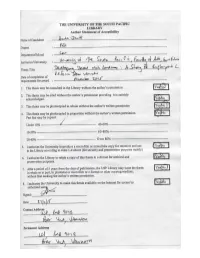

Title and Declaration

DEVELOPING DECENT WORK CONDITIONS: A STUDY OF EMPLOYMENT LAW REFORM FROM VANUATU by Anita Jowitt A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © 2015 by Anita Jowitt, School of Law The University of the South Pacific November 2015 DECLARATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my supervisor Miranda Forsyth. Thank you to people who took the time to comment on drafts, especially Howard Van Trease and Ted Hill. A number of people helped to make sure this was completed. Thank you to Robert Early, Howard Van Trease, John Lynch, Kenneth Chambers and Tess Newton Cain. This thesis was initially conceived following a conversation with the then Director of the Suva Office of the International Labour Organisation, Werner Blenk in 2009. It had been almost entirely written by January 2012, and was initially submitted in December 2012. Since the bulk of the work was completed I have had the privilege of using my academic work practically as a member of the Vanuatu Tripartite Labour Advisory Council. I have the greatest respect for all the people who have worked, and continue to work practically on employment law reforms in Vanuatu, including colleagues on the Vanuatu Tripartite Labour Advisory Council, International Labour Organisation advisors, members of the Vanuatu Chamber of Commerce and Industry and trade union representatives. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to take work done to meet academic requirements and use parts of it in practice, hopefully for the benefit of all. i ABSTRACT In November 2008 the Vanuatu parliament passed a Bill to amend the Employment Act [Cap 160] (the 2008 reform), which significantly increased benefits for employees. -

Tonga and Vanuatu

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Tonga and Vanuatu Report of the Australian Parliamentary Delegation 22 July to 1 August 2009 © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 ISBN 978-0-642-79239-6 For further information about the Australian Parliament contact: Parliamentary Relations Office Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 4360 Fax: (02) 6277 2000 Email: [email protected] Printed by the Department of the House of Representatives Contents Membership of the Delegation ............................................................................................................. v Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... vi 1 Delegation to Tonga and Vanuatu ....................................................................... 1 The delegation ........................................................................................................................... 1 Aims and objectives ................................................................................................................. 1 2 Tonga ...................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Economic and Trade issues..................................................................................................... 4 Tourism ..................................................................................................................................... -

P Olitical Reviews • Melane S I a 461 Va N Uat U

p olitical reviews • melane s i a 461 PhD dissertation, Department of Political in complaints that he had effectively Science, Northern Illinois University. bought a diplomatic passport. Post-Courier. Daily. Port Moresby. Throughout the year his business interests in Vanuatu and involvement World Bank. 2002. Papua New Guinea: with various politicians increased, World Bank Approves the Release of the raising some concerns. Toward the Second Tranche under the Governance Promotion Adjustment Loan. News end of 20 0 0 Gh o s h ’s involvement with Release 2002 /170/s, Washington d c. the Vanuatu government took a some- what bizarre turn as he presented the country with a gift of a ruby allegedly worth u s$174 million. The stated V a n u a t u purpose of this gift was “that it could be used as collateral to get financial Vanuatu experienced another change assistance” (TP, 6 Dec 2000). No of government as a result of a no- independent valuation of th is ruby wa s confidence motion in 2001. While no- available however, nor was it available confidence motions have formed part to be inspected by customs officers. of the political landscape in Vanuatu The ruby’s valuation on Australian in recent years, what made this event customs declaration forms was only extraordinary was the involvement of u s$40,000, casting further doubt on the Supreme Court in the parliamen- its value. ta ry wrangles. These events have dom- In March of 2001 dealings between inated politics in Vanuatu in 2001. Ghosh and the Vanuatu government At the beginning of the year the took a further strange turn when it government was a coalition headed by was revealed that the government had Barak Sope of the Melanesian Prog re s- signed an agreement with Ghosh that sive Party. -

A Coup That Failed? Recent Political Events in Vanuatu

A COUP THAT FAILED? RECENT POLITICAL EVENTS IN VANUATU DAVID AMBROSE SUMMARY supporters, party loyalty was quickly subordinated to rival ambitions, and personal allegiance When Vanuatu conducted its fourth post became a tradeable good in the race for the independence general election, in November last top job. year, more was at stake perhaps than in any The corruption of political processes, which previous election. oon accompanied (or drove) the quest for power, For the first twelve years of independence, the led to more and more desperate stratagems to country's anglophone majority had held secure the prize. goverm11ent through the same party, the Vanua'aku In the tense few weeks that followed the Party (VP), and its constituents had enjoyed the formation of government on 21 December, a benefits that power and the scope for preferment number of key actors showed themselve quite that being in office brings. willing to knowingly flout convention and even For many anglophone politicians and (knowingly?) to exceed their legal authority. constituents alike, therefore, the four years spent in Ultimately,judicial decision defeated a raft of Opposition, 1991-1995, were a painful lesson in purported Executive actions which, taken together, the consequences of electoral defeat. seem to have been intended to effect an By contrast, the francophone minority, who administrative coup d'etat. had endured more than a decade of, in their view, disadvantage and discrimination under anglophone INTRODUCTION rule, finally won office in 1991 and had begun to redress those years of perceived injustice and A recital of events fi·om shortly before the general inequality. -

Papua New Guinea National Elections

Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group PAPUA NEW GUINEA NATIONAL ELECTIONS June – July 2012 COMMONWEALTH SECRETARIAT Table of Contents Letter of Transmittal Chapter 1 - Introduction Terms of Reference 1 Activities 1 Chapter 2 – Political Background 3 Early and Colonial History 3 Post-Independence Politics 3 The 2011-12 political crisis 4 Papua New Guinea and the Commonwealth 7 Chapter 3 – The Electoral Framework and Election Administration 8 International and Regional Commitments, and National Legal Framework 8 The Electoral System 8 The Papua New Guinea Electoral Commission 9 Voter Eligibility and Voter Registration 11 Candidate Eligibility and Nomination 11 Election Offences and Election Petitions 12 Key Issues: 12 Election Boundaries and equal suffrage 12 Voter Registration and the Electoral Roll 13 Election Administration 14 Women’s Participation and Representation 15 Recommendations 17 Chapter 4 – The Election Campaign and Media 18 Campaign Calendar 18 The Campaign Environment 18 Political Parties 18 Key Issues: 19 Campaign Financing and “money politics” 19 Media 19 The Media and the Campaign 20 Voter Education 21 Recommendations 22 Chapter 5 – Voting, Counting and Tabulation 23 Opening and Voting Procedures 23 Key issues: Opening and Voting 24 Delays and reduced voting hours 24 i The electoral roll 24 Ballot boxes 25 Filling in the ballot papers 25 Secrecy of the ballot and adherence to Polling Procedures 25 Women’s participation 27 Voters with a disability 27 Young people and elderly people 28 Procedures for the Count 28 Key -

Political Reviews • Melanesia 401 Tarcisius Tara

political reviews • melanesia 401 between the government and the Tarawa, Republic of Kiribati, 27–30 Solomon Islands Public Employee October. Union, which started in September, ___. 2003. Forum Communiqué. 34th was still unresolved. Public employees Pacific Islands Forum, Auckland, New had requested a pay rise, which was Zealand, 14–16 August. approved by Cabinet, but then turned sibc, Solomon Islands Broadcasting Cor- down by the prime minister. This poration. <http//:www.sibconline.com.sb> issued spilled over into 2004. While much of the media coverage sig, Solomon Islands Government. 2003. and commentaries on Solomon 2004 Budget Speech. Honiara: Ministry of Finance. Islands concentrated on the negative impacts of the civil unrest, the events undp, United Nations Development Pro- of the past five years have also had a gram. 2003. Human Development Report positive twist: they have forced 2003. New York: undp. Solomon Islanders to come to terms with the challenges of building a nation-state out of culturally and eth- Vanuatu nically plural societies, and reflect on the social, political, and economic At the beginning of 2003 Vanuatu was challenges for the future. Governor- governed by a coalition of the Vanua- General Sir John Lapli, for instance, ‘aku Party (vp), headed by the prime said that among the “pillars of minister, Edward Natapei, and the national unity and nation building” Union of Moderate Parties (ump), must be “good beneficial reasons for headed by the deputy prime minister, people of diverse and scattered islands Serge Vohor. Politics in Vanuatu were of Solomon Islands to want to belong dominated by events in three main to this country.” The reasons for stay- areas during that year: the manage- ing together, the governor-general ment of the Vanuatu Commodities said, “must be sound, attainable, sus- Marketing Board (vcmb); the man- tainable and tolerated by these diverse agement of the Vanuatu Maritime people” (sibc, 23 Sept 2003). -

National Disability Policy & Plan of Action 2008-2015

GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF VANUATU NNAATTIIOONNAALL DDIISSAABBIILLIITTYY PPOOLLIICCYY AANNDD PPLLAANN OOFF AACCTTIIOONN 22000088--22001155 MINISTRY OF JUSTICE & SOCIAL WELFARE AND THE NATIONAL DISABILITY COMMITTEE ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS …………………………………………………………...................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………………………………………………………....................................... iii FORWARD ................................................................................................................ v ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... vii 1. INTRODUCTION ….............................................................................................. 1 2. DEVELOPMENT OF THE NATIONAL DISABILITY POLICY & PLAN OF ACTION 2007- 2 2015 ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3. COLLABORATION / CONSULTATION BETWEEN GOVERNMENT AND NGOS ……............. 2 4. RATIONAL FOR THE NATIONAL DISABILITY POLICY ……………………………………………. 3 4.1 National Vision …………………………………………………………………………………. 3 4.2 Principles & Commitments Guiding the National Disability Policy & Plan of 4 Action ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4.3 International Context ………………………………………………………………………… 8 4.4 National Context ……………………………………………………………………………….. 10 5. STATEMENT ON DISABILITY ……………………………………………………………………………. 12 6. FRAMEWORK FOR THE NATIONAL DISABILITY POLICY ……………………………………….. 13 7. NATIONAL DISABILITY POLICY & NATIONAL PLAN OF ACTION 2007-2015 ………… 14 7.1 Policy Statement ……………………………………………………………………………………. -

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

United Nations CEDAW/C/VUT/1-3 Convention on the Elimination Distr.: General of All Forms of Discrimination 30 November 2005 against Women Original: English Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under Article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women Combined initial, second and third periodic reports of States parties Vanuatu* * The present report is being issued without formal editing. 05-62504 (E) 160306 *0562504* CEDAW/C/VUT/1-3 SEPTEMBER 2004 MAP OF VANUATU N Source: National Statistics Office, 2004. 2 CEDAW/C/VUT/1-3 OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER AND DEPARTMENT OF WOMEN’S AFFAIRS PORT VILA, VANUATU Combined Initial, Second and Third Reports on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women SEPTEMBER 2004 3 CEDAW/C/VUT/1-3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT FUNDING FOR THE COMPILATION OF THE CEDAW REPORT WAS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY THE NEW ZEALAND HIGH COMMISSION AND THE AUSTRALIAN HIGH COMMISSION, PORT VILA AND, FOR TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE, BY UNIFEM PACIFIC. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents …………………………………..…………………………............... 4 List of Tables ……………………………………………………………………………... 5 List of Figures .………………………………………………..………………............... 5 List of Boxes ……………………………………………………………………………... 6 List of Abbreviations ..…………………………………..……………………............... 7 Article 18 Reporting on the Convention …………….………………………….............. 9 Background ....………………………………………………………………………....... 9 Article 1 Definition of Discrimination