CISD Yearbook of Global Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 29

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 29 April 2015 9455 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 29 April 2015 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. 9456 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 29 April 2015 THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. -

Wir Sind Die Medien

Marcus Michaelsen Wir sind die Medien Kultur und soziale Praxis Marcus Michaelsen (Dr. phil.) promovierte in Medien- und Kommunikations- wissenschaft an der Universität Erfurt. Seine Forschungsschwerpunkte sind digitale Medien, Demokratisierung sowie die Politik und Gesellschaft Irans. Marcus Michaelsen Wir sind die Medien Internet und politischer Wandel in Iran Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution-NonCom- mercial-NoDerivs 4.0 Lizenz (BY-NC-ND). Diese Lizenz erlaubt die private Nutzung, gestattet aber keine Bearbeitung und keine kommerzielle Nutzung. Weitere Informationen finden Sie unter https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de/. Um Genehmigungen für Adaptionen, Übersetzungen, Derivate oder Wieder- verwendung zu kommerziellen Zwecken einzuholen, wenden Sie sich bitte an [email protected] © 2013 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Die Verwertung der Texte und Bilder ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages ur- heberrechtswidrig und strafbar. Das gilt auch für Vervielfältigungen, Über- setzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und für die Verarbeitung mit elektronischen Systemen. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagkonzept: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Umschlagabbildung: Zohreh Soleimani Lektorat & Satz: Marcus Michaelsen Druck: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-2311-6 -

2014-2015 Report on Police Violence in the Umbrella Movement

! ! ! ! ! 2014-2015 Report on Police Violence in the Umbrella Movement A report of the State Violence Database Project in Hong Kong Compiled by The Professional Commons and Hong Kong In-Media ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! About!us! ! About!the!research! ! Maps!/!Glossary! ! Executive!Summary! ! 1.! Report!on!physical!injury!and!mental!trauma!...........................................................................................!13! 1.1! Physical!injury!....................................................................................................................................!13! 1.1.1! Injury!caused!by!police’s!direct!smacking,!beating!and!disperse!actions!..................................!14! 1.1.2! Excessive!use!of!force!during!the!arrest!process!.......................................................................!24! 1.1.3! Connivance!at!violence,!causing!injury!to!many!.......................................................................!28! 1.1.4! Delay!of!rescue!and!assault!on!medical!volunteers!..................................................................!33! 1.1.5! Police’s!use!of!violence!or!connivance!at!violence!against!journalists!......................................!35! 1.2! Psychological!trauma!.........................................................................................................................!39! 1.2.1! Psychological!trauma!caused!by!use!of!tear!gas!by!the!police!..................................................!39! 1.2.2! Psychological!trauma!resulting!from!violence!...........................................................................!41! -

19-10-2016, Morning

October 19th, 2016 COUNTY ASSEMBLY PROCEEDINGS 1 COUNTY ASSEMBLY OF KISII HANSARD Wednesday, 19th October, 2016 House sat at the County Assembly Chambers at 0902hrs Hon. Speaker {Kerosi Ondieki} in the Chair PRAYERS HON. SPEAKER: Can we proceed with the Orders of the day! MESSAGES Who is the acting Leader of Majority? I will assume that there is no Leader of Majority. Next order! STATEMENTS Honorable Onukoh, I have a Supplementary Order Paper where I have slotted some of the Statements you gave me yesterday and I allowed them under the Standing Order No. 1 and the powers of the Speaker that you can actually do them today. In which sequence do you want to do them? HON. SAMUEL ONUKOH: Thank you Mr. Speaker sir for according me the opportunity and for your consideration. There are three Statements I want to read and present in this House. THE BUDGET REVIEW AND OUTLOOK PAPER FROM THE TREASURY I will start with the Statement that requires the County Treasury to give us a Budget Review and Outlook Paper (CBROP) as envisaged in the Public Finance Act Section 118. HON. SPEAKER: Number 3. HON. SAMUEL ONUKOH: Number 3 Mr. Speaker sir. Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Hansard Report is for information purposes only. A certified Official version of this Report can be obtained from the Hansard Editor. October 19th, 2016 COUNTY ASSEMBLY PROCEEDINGS 2 HON. SPEAKER: Proceed. HON. SAMUEL ONUKOH: Mr. Speaker sir, according to the Public Finance Management (PFM) Act Section 118; County Treasury to prepare a County Budget Review and Outlook Paper and it says in (1) The County Treasury shall… and Mr. -

Modernization and Political Parties: a Case Study of the Hashemi Rafsanjani Administration

Modernization and Political Parties: A Case Study of the Hashemi Rafsanjani Administration * Prof. Dr. Elaheh Koolaee Professor of Regional Studies, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. ** Dr. Yousef Mazarei PhD of Political Science, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. Abstract This paper aims to explore the emergence of a political and social phenomenon, namely political parties, during a specific period in the history of contemporary Iran, in order to move beyond simple analyses and present a deeper and more accurate understanding of political parties in Iran. The question thatthis paper aims to answer pertains to the emergence (ISJ) Studies / Journal No. International of the Executives of the Construction of Iran Party (Kargozaran-e Sazandegi-e Iran) and the role of the Hashemi Rafsanjani administration’s modernization efforts. In order to do so, among three main theories, modernization theory has been selected as the theoretical framework. The paper also uses secondary data analysis as its methodology. In new theories of modernization, instead of focusing on ‘ideal types’, the focus is shifted toward historical features specific to each society. The findings of this research demonstrate that there is a direct link between the HashemiRafsaniani administration’s modernizations and the emergence of 57 / the Executives of the Construction of Iran Party (Kargozaran Party). This V administration’s modernization efforts caused a significant shift in Iran’s development indexes, which resulted in the revival of Iran’s new middle class and provided a basis for the foundation of Kargozaran Party and its victories in subsequent elections. The party became the major proponent of political and economic reform, social liberties, and cultural tolerance in Iran’s political arena. -

Masarykova Univerzita Filozofická Fakulta Seminář Čínských Studií Kulturní Studia Číny

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Seminář čínských studií Kulturní studia Číny Monika Schrammová PROTESTNÍ HNUTÍ NA TAIWANU A V HONGKONGU V ROCE 2014 Protest Movements in Taiwan and Hong Kong in 2014 Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Bc. Denisa Hilbertová, M.A Brno 2018 Prohlášení o autorství práce Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma Protestní hnutí na Taiwanu a v Hongkongu v roce 2014 vypracovala samostatně pod vedením Mgr. Bc. Denisy Hilbertové, M. A. a použila jen zdroje uvedené v seznamu literatury. V Brně, dne 18. května 2018 ………………………………. Podpis autora práce Poděkování Ráda bych na tomto místě poděkovala Mgr. Bc. Denise Hilbertové, M. A. za vedení práce, odbornou pomoc a cenné rady, které mi při jejím zpracování poskytla. Dále bych také chtěla poděkovat své rodině a Marku Jahnovi za jejich podporu během studia. Ediční poznámka V předkládané bakalářské práci je pro zápis čínských jmen a toponym využíváno mezinárodně uznávaného transkripčního přepisu pinyin s výjimkou některých již zavedených názvů míst nebo osob, například Peking, Taiwan, Kuomintang atd. Jiné čínské termíny a úryvky z primárních zdrojů psané v čínských znacích ve standartní zjednodušené podobě jsou opatřeny přepisem s označením tónů. Názvy organizací, skupin, hnutí a dalších institucí, které nemají oficiální český překlad jsou přeloženy do češtiny a doplněny o anglický název. Názvy míst jsou pro lepší dohledatelnost ponechány v angličtině a doplněny o čínské znaky. V práci je využíván název Taiwan (oproti oficiálnímu názvu Čínská republika) pro jasné rozlišení oproti Čínské lidové republice (pevninská Čína), dále ČLR. Také oficiální název Zvláštní administrativní oblast Čínské lidové republiky Hongkong je v práci zkrácen pouze na zavedený název Hongkong, případně zkratku SAR. -

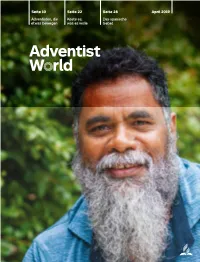

Adventist World

Seite 10 Seite 22 Seite 28 April 2019 Adventisten, die Koste es, Das spanische etwas bewegen was es wolle Gebet Geschichte schreiben VON BILL KNOTT as wir im Geschichtsunterricht gelernt haben, hat unsere Vision Wvon unserem Leben mehr geprägt, als uns bewusst war. Wie in den meisten Kulturen der Welt gemeinhin gelehrt wird, ist „Geschichte“ eine Schilderung von großen – oder schrecklichen – Dingen, die von privilegierten Menschen in entscheidenden Momenten im Leben eines Stammes, eines Volkes oder einer Nation gesagt oder getan wurden. Diese Theorie vom „großen Mann“ in der Geschichte reduziert jedoch zwangsläufig unsere Erwartungen an uns selbst. Wenn Geschichte, die australien es wert ist, aufgezeichnet zu werden, von anderen gemacht wird, die wichtige Dinge auf Bühnen sagen oder tun, auf die wir nie einen Fuß setzen werden, wird unsere Verantwortung für die Veränderung der Welt um uns herum irgendwie geringer. Hunger, so nehmen wir an, ist ein Pro- blem, das die Politiker lösen müssen. Frieden zu schaffen ist die Aufgabe Zum Titelbild ausgebildeter Diplomaten, die zwischen den Hauptstädten dieser Welt Kelvin Coleman kommt aus Kuranda, einer hin und her pendeln. Eine faire Behandlung der Menschen wird nur dann kleinen Stadt in der Nähe von Cairns im passieren, wenn Parlamentsabgeordnete in einer getäfelten Kammer mit australischen Bundesstaat Queensland. Er knapper Mehrheit ein Reformgesetz beschließen. nahm vor kurzem an einem landesweiten Aber es gibt noch einen anderen Handlungsstrang einen, der von Jesus Camp für die Arbeit unter den Aborigines gelehrt und gelebt wurde, und der jeden Gläubigen, auch wenn er noch und den Torres-Strait-Insulanern (Abori- so bescheiden und unbedeutend zu sein scheint, zu einem Wendepunkt ginal and Torres Strait Islander Ministries, der Geschichte macht. -

Somalia, Kenya Leaders Thank Amir for Efforts to Mend Ties

1996 - 2021 SILVER JUBILEE YEAR Bank of England Nadal reaches expects best year Madrid for UK economy quarters, Barty since 1941 into final Business | 13 Sport | 16 FRIDAY 7 MAY 2021 25 RAMADAN - 1442 VOLUME 26 NUMBER 8615 www.thepeninsula.qa 2 RIYALS Somalia, Kenya leaders thank Amir for efforts to mend ties QNA — DOHA During the phone call, President of Kenya expressed his sincere Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin thanks to H H the Amir for Qatar’s Hamad Al Thani held a telephone efforts and endeavours to heal the conversation with President of rift between Kenya and Somalia, “I congratulate both H E President Farmajo and H E President the Federal Republic of Somalia, which resulted in the restoration Kenyatta, for their wise and courageous decision to restore H E Mohamed Abdullahi of diplomatic relations between diplomatic relations between Somalia and Kenya. Our Farmajo, last evening. the two countries. H H the Amir sincere wishes to the two neighbouring countries and their During the phone call, the expressed his congratulations to people for security and stability. I would like also assure Somali President expressed his President of Kenya for this wise that the State of Qatar will always strive for good relations sincere thanks to H H the Amir decision. and remain a peace maker.” for the State of Qatar’s efforts and H H the Amir also congratu- endeavours to heal the rift lated President of Somalia and between the Federal Republic of President of Kenya for their Somalia and the Republic of decision to restore diplomatic their people for security and relations and means of sup- Kenya, which resulted in the res- relations. -

2021 Year Ahead

2021 YEAR AHEAD Claudio Brocado Anthony Brocado January 29, 2021 1 2020 turned out to be quite unusual. What may the year ahead and beyond bring? As the year got started, the consensus was that a strong 2019 for equities would be followed by a positive first half, after which meaningful volatility would kick in due to the US presidential election. In the spirit of our prefer- ence for a contrarian stance, we had expected somewhat the opposite: some profit-taking in the first half of 2020, followed by a rally that would result in a positive balance at year-end. But in the way of the markets – which always tend to catch the largest number of participants off guard – we had what some would argue was one of the strangest years in recent memory. 2 2020 turned out to be a very eventful year. The global virus crisis (GVC) brought about by the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic was something no serious market observer had anticipated as 2020 got started. Volatility had been all but nonexistent early in what we call ‘the new 20s’, which had led us to expect the few remaining volatile asset classes, such as cryptocurrencies, to benefit from the search for more extreme price swings. We had expected volatilities across asset classes to show some convergence. The markets delivered, but not in the direction we had expected. Volatilities surged higher across many assets, with the CBOE volatility index (VIX) reaching some of the highest readings in many years. As it became clear that what was commonly called the novel coronavirus would bring about a pandemic as it spread to the remotest corners of the world at record speeds, the markets feared the worst. -

Chapter 15 Administering and Regulating Security And

CHAPTER 15 ADMINISTERING AND REGULATING SECURITY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN KENYA AND AFRICA This Chapter may be cited as Ben Sihanya (forthcoming 2021) “Administering and Regulating Security and Criminal Justice in Kenya and Africa,” in Ben Sihanya (2021) Constitutional Democracy, Regulatory and Administrative Law in Kenya and Africa Vol. 1: Presidency, Premier, Legislature, Judiciary, Commissions, Devolution, Bureaucracy and Administrative Justice in Kenya Sihanya Mentoring & Prof Ben Sihanya Advocates, Nairobi & Siaya 15.1 Conceptualizing Security and the Criminal Justice System in Kenya and Africa My overarching argument is that national or public security has a narrow and a broad meaning and significance which are equally important in the quest for constitutional democracy in Kenya and Africa.1 In this chapter, security and criminal justice is problematized and conceptualized using the Afro-Kenyanist methodology and approach, with elaborate anecdotes and references to Kenyan and African scholarship. What are some of the key issues in the constitutional, legislative, policy and administrative debate in the context of the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI)…. How has security and the criminal justice system (CJS) been conceptualized, problematized, and contextualized in Kenya and Africa? Significantly, in Kenya and some African states, security is a human right. It is also a core function and obligation of the Executive and the President and or Prime Minister. Art 238(1) of the Constitution defines national security thus: “National security is the protection against internal and external threats to Kenya’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, its people, their rights, freedoms, property, peace, stability and prosperity, and other national interests.”2 And Article 29 also guarantees security as a human right. -

14Th September, 2017 TO; the Secretary Judicial Service

14th September, 2017 TO; The Secretary Judicial Service Commission Supreme Court Building NAIROBI Dear Madam, RE: PETITION AGAINST JUSTICE DAVID MARAGA Chief Justice & President of Supreme Court A. COMPLAINTS & FACTS THEREOF 1.0 Violation of Regulation 12 of The Judicial Code of Conduct & Ethics The Chief Justice has invited, encouraged and permitted entry into the core of the Judiciary by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) who are known protagonists of the President and Deputy President and who propagated the prosecution of the President and Deputy President at the International Criminal Court (ICC). These elements have now captured the Judiciary with the intent of procuring a regime change through judicial radicalism. The Chief Justice has, inter alia; a) Invited, facilitated and supported the embedding of technical support and financing by the International Development Law Organization (IDLO) to entities within the Judiciary including the Judicial Training Institute, National Council for Administration of Justice and Judicial Election Committee, with full knowledge that the IDLO organization is associated with the known anti-government partisan protagonists, including Makau Mutua who is a Board Member thereof; with full knowledge that the entity collaborates with local non-state actors that participated in prosecuting the President and Deputy President at the I.C.C; with full knowledge that the entity is further associated with local non-governmental organizations and individuals who petitioned against the election of the President -

Tightening the Reins How Khamenei Makes Decisions

MEHDI KHALAJI TIGHTENING THE REINS HOW KHAMENEI MAKES DECISIONS MEHDI KHALAJI TIGHTENING THE REINS HOW KHAMENEI MAKES DECISIONS POLICY FOCUS 126 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org Policy Focus 126 | March 2014 The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including pho- tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2014 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei holds a weapon as he speaks at the University of Tehran. (Reuters/Raheb Homavandi). Design: 1000 Colors CONTENTS Executive Summary | V 1. Introduction | 1 2. Life and Thought of the Leader | 7 3. Khamenei’s Values | 15 4. Khamenei’s Advisors | 20 5. Khamenei vs the Clergy | 27 6. Khamenei vs the President | 34 7. Khamenei vs Political Institutions | 44 8. Khamenei’s Relationship with the IRGC | 52 9. Conclusion | 61 Appendix: Profile of Hassan Rouhani | 65 About the Author | 72 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EVEN UNDER ITS MOST DESPOTIC REGIMES , modern Iran has long been governed with some degree of consensus among elite factions. Leaders have conceded to or co-opted rivals when necessary to maintain their grip on power, and the current regime is no excep- tion.