Replace This with the Actual Title Using All Caps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Argentina (Custom Tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour Leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-Guided by Sam Woods

Northwest Argentina (custom tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-guided by Sam Woods Trip Report by Andrés Vásquez; most photos by Sam Woods, a few by Andrés V. Elegant Crested-Tinamou at Los Cardones NP near Cachi; photo by Sam Woods Introduction: Northwest Argentina is an incredible place and a wonderful birding destination. It is one of those locations you feel like you are crossing through Wonderland when you drive along some of the most beautiful landscapes in South America adorned by dramatic rock formations and deep-blue lakes. So you want to stop every few kilometers to take pictures and when you look at those shots in your camera you know it will never capture the incredible landscape and the breathtaking feeling that you had during that moment. Then you realize it will be impossible to explain to your relatives once at home how sensational the trip was, so you breathe deeply and just enjoy the moment without caring about any other thing in life. This trip combines a large amount of quite contrasting environments and ecosystems, from the lush humid Yungas cloud forest to dry high Altiplano and Puna, stopping at various lakes and wetlands on various altitudes and ending on the drier upper Chaco forest. Tropical Birding Tours Northwest Argentina, Nov.2015 p.1 Sam recording memories near Tres Cruces, Jujuy; photo by Andrés V. All this is combined with some very special birds, several endemic to Argentina and many restricted to the high Andes of central South America. Highlights for this trip included Red-throated -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

A Comprehensive Multilocus Phylogeny of the Neotropical Cotingas

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 81 (2014) 120–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A comprehensive multilocus phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae, Aves) with a comparative evolutionary analysis of breeding system and plumage dimorphism and a revised phylogenetic classification ⇑ Jacob S. Berv 1, Richard O. Prum Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208105, New Haven, CT 06520, USA article info abstract Article history: The Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae: Aves) are a group of passerine birds that are characterized by Received 18 April 2014 extreme diversity in morphology, ecology, breeding system, and behavior. Here, we present a compre- Revised 24 July 2014 hensive phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas based on six nuclear and mitochondrial loci (7500 bp) Accepted 6 September 2014 for a sample of 61 cotinga species in all 25 genera, and 22 species of suboscine outgroups. Our taxon sam- Available online 16 September 2014 ple more than doubles the number of cotinga species studied in previous analyses, and allows us to test the monophyly of the cotingas as well as their intrageneric relationships with high resolution. We ana- Keywords: lyze our genetic data using a Bayesian species tree method, and concatenated Bayesian and maximum Phylogenetics likelihood methods, and present a highly supported phylogenetic hypothesis. We confirm the monophyly Bayesian inference Species-tree of the cotingas, and present the first phylogenetic evidence for the relationships of Phibalura flavirostris as Sexual selection the sister group to Ampelion and Doliornis, and the paraphyly of Lipaugus with respect to Tijuca. -

Turismo De Observación De Aves En El Santuario Nacional Pampa Hermosa Como Modelo De Desarrollo Sostenible En Los Distritos De San Ramon Y Huasahuasi”

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL MAYOR DE SAN MARCOS FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ADMINISTRATIVAS E. A. P. DE ADMINISRACIÓN DE TURISMO “TURISMO DE OBSERVACIÓN DE AVES EN EL SANTUARIO NACIONAL PAMPA HERMOSA COMO MODELO DE DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE EN LOS DISTRITOS DE SAN RAMON Y HUASAHUASI” TESIS Para optar el título profesional de Licenciada en Administración de Turismo AUTOR Mariella Ines Motta Sevelora ASESOR Cecilia Castillo Yui Lima – Perú 2015 Dedicatoria A Vilma Sevelora, mi madre Al Apu Pampa Hermosa, nuestro eterno hogar A la UNMSM, mi alma mater 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Agradezco infinitamente a mis padres por darme su confianza, apoyo moral y económico en toda mi carrera, gracias a ustedes puedo cumplir uno de mis sueños, ¡Los amo! A mi abuelita Aurelia mi segunda mama por su amor y compañía, a mi abuelito Carlos por nunca perder la fe en este proyecto y darme sus sabios consejos, a mi tío José y mi hermana por su confianza. Agradezco también a mi querida Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos por darme la oportunidad de ser parte de esta travesía de constante aprendizaje que me hace amar y valorar mi hermosa tierra. A mis amigos en especial a María de los Ángeles por sus consejos, apoyo logístico por compartir conmigo sus opiniones y sueños en nuestras largas charlas acerca de Pampa Hermosa, sobre todo por su enorme confianza en este trabajo, a la Sra. Luz Gonzales por darme un espacio en su hogar, por su preocupación y hacerme sentir parte de su familia. Agradecer también a los amigos de Nueva Italia y Ninabamba por su hospitalidad, sencillez, sus risas y su infatigable fortaleza que hacían de mis visitas realmente enriquecedoras y fueron mi ejemplo e inspiración, especialmente al Sr. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Global Variation in Woodpecker Species Richness Shaped by Tree

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2017) 44, 1824–1835 ORIGINAL Global variation in woodpecker species ARTICLE richness shaped by tree availability † † Sigrid Kistrup Ilsøe1, , W. Daniel Kissling2, ,* , Jon Fjeldsa3, Brody Sandel4 and Jens-Christian Svenning1 1Section for Ecoinformatics and Biodiversity, ABSTRACT Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Aim Species richness patterns are generally thought to be determined by abi- DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark, 2Institute for otic variables at broad spatial scales, with biotic factors being only important Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (IBED), University of Amsterdam, 1090 GE at fine spatial scales. However, many organism groups depend intimately on Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 3Center for other organisms, raising questions about this generalization. As an example, Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at woodpeckers (Picidae) are closely associated with trees and woody habitats Natural History Museum of Denmark, because of multiple morphological and ecological specializations. In this study, University of Copenhagen, DK-1350 we test whether this strong biotic association causes woodpecker diversity to be Copenhagen K, Denmark, 4Department of closely linked to tree availability at a global scale. Biology, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, Location Global. CA 95057, USA Methods We used spatial and non-spatial regressions to test for relationships between broad-scale woodpecker species richness and predictor variables describing current and deep-time availability of trees, current climate, Quater- nary climate change, human impact, topographical heterogeneity and biogeo- graphical region. We further used structural equation models to test for direct and indirect effects of predictor variables. Results There was a strong positive relationship between woodpecker species richness and current tree cover and annual precipitation, respectively. -

An Introduction to the Bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes

An introduction to the bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes M.S. Maldonado Fonkén International Mire Conservation Group, Lima, Peru _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY In Peru, the term “bofedales” is used to describe areas of wetland vegetation that may have underlying peat layers. These areas are a key resource for traditional land management at high altitude. Because they retain water in the upper basins of the cordillera, they are important sources of water and forage for domesticated livestock as well as biodiversity hotspots. This article is based on more than six years’ work on bofedales in several regions of Peru. The concept of bofedal is introduced, the typical plant communities are identified and the associated wild mammals, birds and amphibians are described. Also, the most recent studies of peat and carbon storage in bofedales are reviewed. Traditional land use since prehispanic times has involved the management of water and livestock, both of which are essential for maintenance of these ecosystems. The status of bofedales in Peruvian legislation and their representation in natural protected areas and Ramsar sites is outlined. Finally, the main threats to their conservation (overgrazing, peat extraction, mining and development of infrastructure) are identified. KEY WORDS: cushion bog, high-altitude peat; land management; Peru; tropical peatland; wetland _______________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION organic soil or peat and a year-round green appearance which contrasts with the yellow of the The Tropical Andes Cordillera has a complex drier land that surrounds them. This contrast is geography and varied climatic conditions, which especially striking in the xerophytic puna. Bofedales support an enormous heterogeneity of ecosystems are also called “oconales” in several parts of the and high biodiversity (Sagástegui et al. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

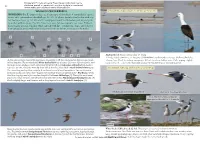

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

Ecuador's Biodiversity Hotspots

Ecuador’s Biodiversity Hotspots Destination: Andes, Amazon & Galapagos Islands, Ecuador Duration: 19 Days Dates: 29th June – 17th July 2018 Exploring various habitats throughout the wonderful & diverse country of Ecuador Spotting a huge male Andean bear & watching as it ripped into & fed on bromeliads Watching a Eastern olingo climbing the cecropia from the decking in Wildsumaco Seeing ~200 species of bird including 33 species of dazzling hummingbirds Watching a Western Galapagos racer hunting, catching & eating a Marine iguana Incredible animals in the Galapagos including nesting flightless cormorants 36 mammal species including Lowland paca, Andean bear & Galapagos fur seals Watching the incredible and tiny Pygmy marmoset in the Amazon near Sacha Lodge Having very close views of 8 different Andean condors including 3 on the ground Having Galapagos sea lions come up & interact with us on the boat and snorkelling Tour Leader / Guides Overview Martin Royle (Royle Safaris Tour Leader) Gustavo (Andean Naturalist Guide) Day 1: Quito / Puembo Francisco (Antisana Reserve Guide) Milton (Cayambe Coca National Park Guide) ‘Campion’ (Wildsumaco Guide) Day 2: Antisana Wilmar (Shanshu), Alex and Erica (Amazonia Guides) Gustavo (Galapagos Islands Guide) Days 3-4: Cayambe Coca Participants Mr. Joe Boyer Days 5-6: Wildsumaco Mrs. Rhoda Boyer-Perkins Day 7: Quito / Puembo Days 8-10: Amazon Day 11: Quito / Puembo Days 12-18: Galapagos Day 19: Quito / Puembo Royle Safaris – 6 Greenhythe Rd, Heald Green, Cheshire, SK8 3NS – 0845 226 8259 – [email protected] Day by Day Breakdown Overview Ecuador may be a small country on a map, but it is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of life and biodiversity. -

First Record of the Austral Negrito (Aves: Passeriformes) from the South Shetlands, Antarctica

vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 297–304, 2015 doi: 10.1515/popore−2015−0018 First record of the Austral Negrito (Aves: Passeriformes) from the South Shetlands, Antarctica Piotr GRYZ 1,2, Małgorzata KORCZAK−ABSHIRE 1* and Alina GERLÉE 3 1 Zakład Biologii Antarktyki, Instytut Biochemii i Biofizyki PAN, ul. Pawińskiego 5a, 02−106 Warszawa, Poland *corresponding author <[email protected]> 2 Instytut Paleobiologii PAN, ul. Twarda 51/55, 00−818 Warszawa, Poland <[email protected]> 3 Zakład Geoekologii, Wydział Geografii i Studiów Regionalnych, Uniwersytet Warszawski, ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 30, 00−927 Warszawa, Poland <[email protected]> Abstract: The order Passeriformes is the most successful group of birds on Earth, however, its representatives are rare visitors beyond the Polar Front zone. Here we report a photo− −documented record of an Austral Negrito (Lessonia rufa), first known occurrence of this species in the South Shetland Islands and only the second such an observation in the Antarc− tic region. This record was made at Lions Rump, King George Island, part of the Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 151 (ASPA 151). There is no direct evidence of how the indi− vidual arrived at Lions Rump, but ship assistance cannot be excluded. Key words: Antarctica, King George Island, avifauna monitoring, Lessonia rufa, vagrant birds. Introduction Monitoring of the avifauna in Admiralty and King George Bays on King George Island (South Shetland Islands, Antarctica; Fig. 1) is an important part of the Polish Antarctic research, and has been conducted since 1977 (Jabłoński 1986; Trivelpiece et al. 1987; Sierakowski 1991; Lesiński 1993; Korczak−Abshire et al. -

Peru: from the Cusco Andes to the Manu

The critically endangered Royal Cinclodes - our bird-of-the-trip (all photos taken on this tour by Pete Morris) PERU: FROM THE CUSCO ANDES TO THE MANU 26 JULY – 12 AUGUST 2017 LEADERS: PETE MORRIS and GUNNAR ENGBLOM This brand new itinerary really was a tour of two halves! For the frst half of the tour we really were up on the roof of the world, exploring the Andes that surround Cusco up to altitudes in excess of 4000m. Cold clear air and fantastic snow-clad peaks were the order of the day here as we went about our task of seeking out a number of scarce, localized and seldom-seen endemics. For the second half of the tour we plunged down off of the mountains and took the long snaking Manu Road, right down to the Amazon basin. Here we traded the mountainous peaks for vistas of forest that stretched as far as the eye could see in one of the planet’s most diverse regions. Here, the temperatures rose in line with our ever growing list of sightings! In all, we amassed a grand total of 537 species of birds, including 36 which provided audio encounters only! As we all know though, it’s not necessarily the shear number of species that counts, but more the quality, and we found many high quality species. New species for the Birdquest life list included Apurimac Spinetail, Vilcabamba Thistletail, Am- pay (still to be described) and Vilcabamba Tapaculos and Apurimac Brushfnch, whilst other montane goodies included the stunning Bearded Mountaineer, White-tufted Sunbeam the critically endangered Royal Cinclodes, 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Peru: From the Cusco Andes to The Manu 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com These wonderful Blue-headed Macaws were a brilliant highlight near to Atalaya.