The Change Agentsalinskyian Organizing Among Religious

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charity Workers Hit Budget Cuts

Charity workers hit budget cuts 'No matfer what hap- pens in Washington, the poor will still be there, the aged will still be there LAS VEGAS (NC) - Participants at the annual meeting of the National Con- ference of Catholic Charities ex- pressed concern about the short- and long-range effects of the Reagan ad- ministration budget cuts on the poor, the choice of Las Vegas for a meeting site and the role of the handicapped in society. Concern about the fate of the poor under the Reagan budget cuts - was summed up by one delegate, who said: "No matter what happens in Washington, the poor will still be there; the aged will still be there, the sick will be there and so will all those others who have depended upon us for counseling, for advocacy, for con- cern. We cannot abandon them, even, or especially if, the government does." CONCERN ABOUT a national charities convention being held in the gambling center of Las Vegas was ad- dressed by Bishop Norman F. Mc- Farland of Reno in his homily during YELLOW BRICK ROAD — School walls have never been says the kids enjoy the mural based on 'The Wiz' (Wizard the opening liturgy in Guardian Angel known for their excitement, but St. Francis Xavier School of Oz) which took several months to complete. Voice Cathedral - which is adjacent to the in Miami's inner city has proved that this isn't always the Photo by Prent Browning. Las Vegas strip. case. Fr. Bill Mason, standing with artist Marvin Parker, "The choice of Las Vegas as your J convention site this year was not without expressed concern and Likewise, church members in Also at the meeting, delegates alliances to develop programs for serious reservations on the part of Nevada, "who live and work here, handicapped persons. -

Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award

PACEM IN TERRIS PEACE AND FREEDOM AWARD October 3, 2002 I S'Ambrose University Davenport, Iowa 2002 PACEM IN TERRIS PEACE AND FREEDOM AWARD PROGRAM MUSICAL PRELUDE Spirit, Ine. MASTER OF CEREMONIES Jerri Leinen OPENING PRAYER Sr. Mary Bea Snyder, CHM MUSICAL INTERLUDE Chris Inserra HISTORY OF AWARD "This is what we are about." Msgr. Marvin Mottet "We plant the seeds that one day will grow. We HONORING PAST RECIPIENTS water the seeds already planted, knowing that Rev. Ron Quay and Sr. Dorothy Heiderscheit, OSF they hold future promise. We lay foundations that will need further development. We provide REMEMBERING SR. MIRIAM HENNESSEY, OSF yeast that produces effects far beyond our Barb Gross capabilities ... " REMEMBERING FR. RON HENNESSEY "We may never see the results, but that is the Sr. Kay Forkenbrock, OSF difference between the Master Builder and the BIOGRAPHY OF THE RECIPIENTS worker. We are workers, not Master Builders. DeAnn Stone Ebener We are ministers, not messiahs." AWARD PRESENTATION "We are prophets of a future not our own." Bishop William Franklin - Archbishop Oscar Romero REMARKS Sr. Dorothy Marie Hennessey, OSF and Sr. Gwen Hennessey, OSF CLOSING PRAYER Rev. Katherine Mulhern 2 3 PACEM IN TERRIS Helen M. Caldicott's work as a physician and peace advocate gave her a powerful voice which spoke on behalf of the PEACE AND FREEDOM world's children in the face of possible nuclear holocaust. AWARD (1983) Cardinal Joseph Bernardin taught us through his notion of John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States, the "seamless garment" that all life is God-given, and awakened in us a hope that no problem was too great to therefore precious. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Dear Syd... by Jubilee Mosley Dear Evan Hansen Star Sam Tutty Joins Hollyoaks

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Dear Syd... by Jubilee Mosley Dear Evan Hansen star Sam Tutty joins Hollyoaks. The 23-year-old is known for playing the title role in the West End version of Dear Evan Hansen , for which he won an Olivier Award for Best Actor in a musical. The character of Timmy is introduced as a young computer wizard working for Fergus ( Robert Beck ) on his 'bluebird' scam, which involves hidden cameras filming teenage girls. "Working at Hollyoaks is an absolute delight," Tutty said. "Everyone has been so welcoming and have been very supportive whenever I have had any questions. "This mainly goes out to the wonderful Robert Beck who plays Fergus, Timmy's terrifying overseer. "I feel so privileged to play a character like Timmy. He's clearly terrified of those he works for. "His poisoned moral compass has led him down a treacherous path and I'm very excited to see what's at the end." Timmy makes his debut in E4's first-look episode of Hollyoaks on Wednesday, June 2. ID:448908:1false2false3false:QQ:: from db desktop :LenBod:collect1777: Follow us on Twitter @SMEntsFeed and like us on Facebook for the latest entertainment news alerts. Dear Syd... by Jubilee Mosley. Published: 22:56 BST, 6 November 2020 | Updated: 06:46 BST, 7 November 2020. My wife Clare and I are locked away in a small room — just nine paces by four — with a guard outside to make sure we don't come out. We're not allowed visitors and lukewarm meals are delivered in brown paper bags three times a day (7am, midday and 5pm), with fresh linen and towels left outside the door once a week. -

Website NEWS

A M D G BEAUMONT UNION REVIEW. SUMMER 2013 THIS is it –the new style REVIEW; - I hope you find the Website to your liking and easy “to navigate” and I am, of course, open to suggestions as to how it can be improved. There are some advantages to this form of communication. I have been able to include a school history, a section on Trivia and some interesting OBs. The photo gallery will no doubt grow but there are limitations because of cost and time. Then there are the charities which have a close association to Beaumont and links to St John’s and Jerry Hawthorne’s Blog – we are on our way. I am hoping to update THE REVIEW four times a year with editions Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter and back numbers will be placed in “The Library”. Obituaries, which like global warming, are on the increase, I have put in a separate section. There is a “Last updated Box” on the Home Page and a Notice board for anything of immediate importance the Committee would like to draw to your attention. If needs be, I will E-Mail you on matters of urgency. THE REVIEW is available in PDF for those who wish to print a hard copy. THANK YOU “BAILEY BOY” GUY with Lavinia and Charlie. When is the right time to go? When to leave to pursue other interests and hand over the reins, Cash in that annuity and take to the hills? Knowing when to leave is one of the great wisdoms of life and one of the hardest to get right. -

1964 Study Week on the Apostolate

OFFICIAL PROGRAM TION SCHOOL J . vs WAHLERT· HIGH SCHOOL BER20 1963 Dubuque • LETTERMAN RETURNS • • • Almost exclusively an offensive player last In forecasting the coming season, Jim said, year, returning letterman Jim Rymars (42) is "Our backfield is real fast and looks good. slated to be one of the defensive mainstays Our spirit is real strong, and more than com in Assumption's football strategy this year. pensates for any lack of returning veterans. Our defense is also good." Jim looks forward 5'10", 176 lb. Rymars enjoys playing both to the games against West and Central to be offense and defense, and Coach Tom Sunder "real hard-fought contests." bruch has Jim starting tonight in the defensive fullback position. Says Coach Sunderbruch, In the opinions of coaches and team mem "We had Jim playing only offensive ball last bers, Rymars is the combination of a recep year. He developed rapidly, took our coaching tive, coachable, unassuming personality and an real well, and turned out to be a major exceptional football player. As the Times prospect for a defense regular." Democrat Pigskin Prevue said, Rymars is ex pected to "put some punch in the (Assump The coaches all agree that Jim is "a real tion) running attack from the fullback spot." aggressive, 'hard-nosed' kid." They also con Assumption fans are betting on it. cur on the fact that, "He's one of the team's best blockers and we're depending on him in our toughest defensive position." Another of Jim's as ets is his speed. Said Coach Sunderbruch, "Jim really surprised us. -

Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award

Pacem in terris Peace and Freedom Award Tuesday, April 9, 2019 DAVENPORT, IOWA His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama is the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism. He was born in 1935 to a farming family in a small hamlet located in Taktser Amdo, Northeastern Tibet. At the age of two, he was recognized as the reincarnation of the previous 13 Dalai Lamas. At age fifteen, on November 17, 1950, he assumed full temporal political duties. In 1959, following the brutal suppression of the Tibetan national uprising in Lhasa by Chinese troops, His Holiness was forced to flee to Dharamsala, Northern India, where he currently lives as a refugee. He has lived in exile for 60 years in northern India, advocating nonviolently and steadfastly on behalf of the Tibetan people for preservation of their culture, language, religion and well-being. China views the Dalai Lama as a threat to its efforts to control Tibet and Buddhism. He was awarded the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize for his non- violent efforts for the liberation of Tibet and concern for global environmental problems. On Oct. 17, 2007, the Dalai Lama received the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal, our country’s highest civilian honor. His Holiness has traveled around the world and spoken about the welfare of Tibetans, the environment, economics, women’s rights and nonviolence. He has held discussions with leaders of different religions and has participated in events promoting inter-religious harmony and understanding. "The world doesn’t belong to leaders. The world belongs to all humanity." His Holiness the Dalai Lama 2 2019 Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award program MUSICAL PRELUDE Christopher Clow WELCOME James Loftus, PhD Vice President, Enrollment Management St. -

Of Paper Is a Link to Our Faith Roots ^Archives a Priceless Treasure

Knights of Columbus convention — Pages 13-15 ¥OL. LX NO. 31 r Each name and piece ' Of paper is a link to our faith roots ^Archives a priceless treasure By Patricia Hillyer Some of the Archive documents are in ^ Register Staff Latin — others are in French, Spanish or The wise man who said that “treasures Italian, reflecting the varied backgrounds are always found in the strangest places,” of the faithful who have comprised Denver ^must have known about the three tiny Church history. rooms on the fourth floor of the Pastoral There is a treasury of material pertinent ^Center where a cache of historical riches to the five bishops who have shepherded the are housed. archdiocese, including their spiritual notes, j, A priceless collection of religious re letters, financial accounts, decisions and cords, unique scrapbooks,, time-worn diaries. The story of Archbishop Urban J. ^ newspapers and original photos span more Vehr's reign is vividly portrayed in four I than a century of local religious history — shelves of scrapbooks carefully assembled from I860 when throngs of gold-seekers first by Sisters who attended the prelate. flooded into Denver City to the present time Bound copies of the Denver Catholic Reg 'Srben the archdiocesan Catholic population ister extend back to 1900 bringing to life the ^tops 250,000. times and people of the Church for the past ' * Known formally as the Archdiocesan 85 years. Archives, the record center is under the Parish histories and the biographies of careful direction of Sister Ann Walter who, priests who served in them, stand beside ^ not only gathers and assembles the moun papers of all of the Religious congregations tain of materials, but also congenially as- of both men and women who have so gener- - -«ists those who stop by to research a his ou^y given their time and talent to the toy Jamas Bses torical monument or search for their roots. -

Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award

Pacem in terris Peace and Freedom Award Sunday, October 22, 2017 DAVENPORT, IOWA 2017 Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award program MUSICAL PRELUDE Christopher Clow WELCOME Widad Akreyi, PhD Sister Joan Lescinski, CSJ, PhD President, St. Ambrose University Dr. Widad Akreyi is a health expert, author and human rights activist of Kurdish ancestry who co-founded the OPENING PRAYER human rights organization Defend International. Alan Ross Born in Akre, Kurdistan region, Iraq, in 1969, she fled Jewish Federation of the Quad Cities with her family to Mosul five years later to avoid the Iraq ONE AMONG US JUSTICE AWARD government’s offensive against Kurds. Violations of human rights that occurred during that, and other offensives, are Introduction believed to have shaped her life. She is said to be the first young Loxi Hopkins woman of Middle Eastern descent to engage in advocacy efforts Presentation related to illicit trade of small arms and light weapons, gender- Most Rev. Thomas Zinkula based violence, disarmament and international security. Bishop, Diocese of Davenport Because of her peace activism and political affiliations, she Acceptance Nora Dvorak was forced to leave her homeland in 1991. She sought political asylum in Denmark, where she enrolled in language studies HISTORY OF PACEM IN TERRIS AWARD and eventually earned a master’s degree in genetics and Dan Ebener, DBA genomics and a PhD in global health and cancer epidemiology. Professor, Organizational Leadership She has served as a clinical geneticist at the Royal Hospital St. Ambrose University in Copenhagen, researching inherited diseases. Dr. Akreyi has created partner agreements with like-minded, LITANY HONORING PAST RECIPIENTS St. -

Sacred .Heart Cathedral. Davenport, Iowa Pacem in Terris Jzlwarcf

Sacred .Heart Cathedral. Davenport, Iowa Pacem In Terris JZlwarcf The Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award was created in 1964 by the Davenport Catholic Interracial Council, which disbanded in 1976. Since that time, the award has been presented by the Quad Cities Pacem in Terris Coalition. The award honors Pope John XXIII and commemorates his 1963 encyclical letter, Pacem In Terris (Peace on Earth), which called on all people to secure peace among all nations. The members of the 1996 Pacem in Terris Coalition are: Diocese of Davenport Contact: Dan R. Ebener (319) 324-1911 St. Ambrose University Contact: Fr. Bill Dawson (319) 333-6374 Churches United of the Quad Cities Contact: Rev. Charles Landon (309) 786-6494 Augustana College Contact: Rev. Jim Winship (309) 794-7214 The Stanley Foundation Contact: Jill Goldesberry (319) 264-6857 Sisters of Humility Contact: Sr. Marcia Costello (319) 323-9466 1996 Pacem In Terris Peace and Freedom. J2tward Program Music St. Mary's Choir Introduction Martha Yerington Welcome Fr. Marvin Mottet Opening Prayer Sr. Jude Fitzpatrick CHM Sr. Johanna Rickl CHM History of Award Jill Goldesberry Honoring Past Recipients Rev. Charles Landon Rev. Manuel Munoz Biography Of Bishop Ruiz Rev. Michael Swartz Rev. Rebecca Johnston Presentation of the Award Bishop William Franklin Acceptance Address Bishop Samuel Ruiz Closing Prayer Rev. Jim Winship Immediatelyfollowing the award presentation q public reception will be held in Sacred Heart Rectory. Bishop Samuel Ruiz is the 26th recipient of the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award Previous recipients are: 1995 Jim Wallis 1993 Daniel Berrigan, s.J. -

Prophetic Voices

A publication for friends of the Congregation of the Humility of Mary continue to speak with the prophetic Prophetic Voices voice of God over and over again – by Lisa Martin, CHM Communications Director advocating for justice, equality, peace, and issued a challenge to combat and dignity. n 1854, in a French village that complacency and apathy in our own was poor both financially and in I lives. Rather than wait for others Looking toward the future of the practice of the faith, the Congregation to solve the problems of inequality, congregation, in 1971 CHMs of the Humility of Mary (CHM) had injustice, and poverty, Sr. Joan established the CHM associate its beginnings. Humility sisters came explained why it is our moral and relationship. It is to provide opportunity together to establish a free school spiritual responsibility to take action to participate as non-vowed persons in for girls, teaching religion, writing, and make the world a better place the spirit and work of the Congregation reading, arithmetic and lace making. for all. of the Humility of Mary-the basis of The sisters were giving voice to the this is the gospel of love. concerns of that era–speaking against This has been the course of CHMs -continued on page 3 the unjust and helping the powerless. for over 165 years: Providing homes for orphans, education for children Photo: CHM Associate Rosemary Hendricks Sister Joan Chittister, OSB recently and adults, healthcare, housing is director of What Does Jesus Do (WDJD) addressed the Communicators for and supportive services for those Mission and carries the word of God on Women Religious conference on “The experiencing homelessness, doing mission trips to Kakuma, Turkana, and Kenya time is Now: A call to Uncommon the work of the gospel and following in East Africa. -

St Ambrose 1948 Football Review

AmbRoskm Oaks DavenpoRt^Iowa dedicated t6... Rt. Rev. Ulrich A. Hauber, P.H.D. Rt. Rev. Ulrich Hauber Fourth President of St. Ambrose College To Msgr. Ulrich A. Hauber, wise teacher, warm friend and patient counsellor of the students for forty-one years, scientist and author of merit whose textbooks are now being used in twenty-six colleges, constant servant of God and Man who possesses the strength, wisdom, and dignity which typify the true Ambrosian spirit, the editors sincerely and proudly dedicate the 1949 Oaks . "Servant of God and Man admirustftatxon building "Shirley" and "Mike" "Bev" and "Bernie" "Tillie" *Gfe*** an<* Jean Library Reading Room MOST REV. RALPH L. HAYES, D. D. Bishop of Davenport President of the College Board of Control 9^.^admfnfstRatto n Rt. Rev. Ambrose J. Burke, S.T.B., Ph. D., LL.D. President of St. Ambrose Rev. Harry J. Toher, A. B. Vice-President Business Manager and Athletic Director Rev. Leo C. Sterck, S.T.B., A.M. The Very Rev. E. M. O'Connor, S.T.B., Ph. D. Dean of Studies and Registrar Philosophy Rector of Ecclesiastical Department \msm Rev. Bernard M. Brugman, A. B. Rev. Bernard M. Kamerick, A. B. Dean of Men Spiritual Director Rev. Fred A. Verbeckmoes, A. B. Rev. Lawrence H. Mork, A. M. Mr. Robert J. Taylor Assistant Business Manager Librarian Business Office Manager Rev. Gerald A. Lillis, S.T.B., Rt. Rev. Ulrich A. Hauber, Ph.D. Rev< w. F. Lynch, S.T.B., Ph.D. Biology Biology Ph.D. Chemistry Rev. John T. Kennedy, Ph.B. -

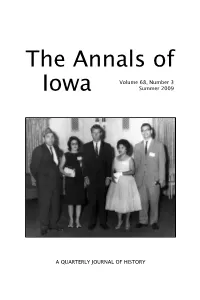

The Annals of Iowa Volume 68, Number 3

The Annals of Volume 68, Number 3 Iowa Summer 2009 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue JANET WEAVER, assistant curator at the Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Libraries, traces the emerging activism of a cadre of second-generation Mexican Americans in Davenport. Many of them grew up in the barrios of Holy City and Cook’s Point in the 1920s and 1930s. By the late 1960s, they were providing local leadership for Cesar Chavez’s grape boycott campaign and lending their support to the fiercely contested passage of Iowa’s first migrant worker legislation. KARA MOLLANO analyzes the campaign led by minority residents of Fort Madison in the 1960s and 1970s to oppose a plan to rebuild U.S. High- way 61 that would have included rerouting the road through neighbor- hoods disproportionately inhabited by African Americans and Mexican Americans. The multiracial and multiethnic coalition succeeded in block- ing the highway plan while exposing racial, ethnic, and class divisions in Fort Madison. Front Cover Ernest Rodriguez (right) was born in a boxcar in Davenport’s “Holy City” in 1928. By 1963, he was meeting with U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy (center) at the American GI Forum convention in Chicago , along with (left to right) Augustine Olvera, Mary Olvera, and Juanita Rodriguez. For more on the emerging activism of Davenport’s Mexican Americans “from barrio to ‘¡boicoteo!’ see Janet Weaver’s article in this issue. Photo courtesy Ernest Rodriguez. Editorial Consultants Rebecca Conard, Middle Tennessee State R. David Edmunds, University of Texas University at Dallas Kathleen Neils Conzen, University of H.