Something Inside So Strong INSIDE SO SOMETHING INSIDE SO STRONG This Report Is Distributed by the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rejecting the De Minimis Defense to Infringement of Sound Recording Copyrights Michael G

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 93 | Issue 4 Article 12 3-2018 Rejecting the De Minimis Defense to Infringement of Sound Recording Copyrights Michael G. Kubik University of Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael G. Kubik, Rejecting the De Minimis Defense to Infringement of Sound Recording Copyrights, 93 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1699 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol93/iss4/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\93-4\NDL412.txt unknown Seq: 1 31-MAY-18 11:29 NOTES REJECTING THE DE MINIMIS DEFENSE TO INFRINGEMENT OF SOUND RECORDING COPYRIGHTS Michael G. Kubik* INTRODUCTION “Get a license or do not sample.”1 The Sixth Circuit’s terse ultimatum in the 2005 Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films decision rejected the com- mon law de minimis2 exception to copying as applied to sound recordings, and for eleven years, Bridgeport stood unchallenged by the courts of appeals, the Supreme Court, and Congress.3 This changed in June 2016 with the Ninth Circuit’s decision in VMG Salsoul, LLC v. Ciccone.4 Confronted with the question of whether the de minimis defense applies to the unauthorized copying of sound recordings, the court openly rejected the Sixth Circuit’s reasoning and held that the de minimis defense applies.5 In doing so, the Ninth Circuit created a circuit split subjecting two centers of the American music industry, Nashville (Sixth Circuit) and Los Angeles (Ninth Circuit), to * Candidate for Juris Doctor, Notre Dame Law School, 2019; Bachelor of Arts, Honors in Philosophy, University of Michigan, 2016. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Homestar Karaoke Song Book

HomeStar Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 10cc Avril Lavigne Good Morning Judge HSW216-04 Sk8er Boi HSW001-07 2 Play B.A. Robertson So Confused HSW022-10 Bang Bang HSG011-08 50 Cent Bang Bang HSW215-01 In Da Club HSG005-05 Knocked It Off HSG011-10 In Da Club HSW013-06 Knocked It Off HSW215-04 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Kool In The Kaftan HSG011-11 21 Questions HSW013-01 Kool In The Kaftan HSW215-05 ABBA To Be Or Not To Be HSG011-12 Chiquitita HSW257-01 To Be Or Not To Be HSW215-09 Chiquitita SFHS104-01 B.A. Robertson & Maggie Bell Dancing Queen HSW251-04 Hold Me HSG011-09 Does Your Mother Know HSW252-01 Hold Me HSW215-02 Fernando HSW257-03 B2K & P. Diddy Fernando SFHS104-02 Bump, Bump, Bump HSW001-02 Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) HSW257-04 Baby Bash Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) SFHS104-04 Suga Suga HSW024-09 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do HSW252-03 Bachelors, The I Have A Dream HSW258-01 Chapel In The Moonlight HSW205-03 I Have A Dream SFHS104-05 I Wouldn't Trade You For The World HSW205-09 Knowing Me, Knowing You HSW257-07 Love Me With All Of Your Heart HSW206-02 Knowing Me, Knowing You SFHS104-06 Ramona HSW206-06 Mama Mia HSW251-07 Bad Manners Money, Money, Money HSW252-05 Buona Sara HSW204-02 Name Of The Game, The HSW258-09 Hey Little Girl HSW204-05 Name Of The Game, The SFHS104-13 Just A Feeling HSG011-03 S.O.S. -

Journal of the Society for American Music Eminem's “My Name

Journal of the Society for American Music http://journals.cambridge.org/SAM Additional services for Journal of the Society for American Music: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Eminem's “My Name Is”: Signifying Whiteness, Rearticulating Race LOREN KAJIKAWA Journal of the Society for American Music / Volume 3 / Issue 03 / August 2009, pp 341 - 363 DOI: 10.1017/S1752196309990459, Published online: 14 July 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1752196309990459 How to cite this article: LOREN KAJIKAWA (2009). Eminem's “My Name Is”: Signifying Whiteness, Rearticulating Race. Journal of the Society for American Music, 3, pp 341-363 doi:10.1017/S1752196309990459 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/SAM, IP address: 140.233.51.181 on 06 Feb 2013 Journal of the Society for American Music (2009) Volume 3, Number 3, pp. 341–363. C 2009 The Society for American Music doi:10.1017/S1752196309990459 ⃝ Eminem’s “My Name Is”: Signifying Whiteness, Rearticulating Race LOREN KAJIKAWA Abstract Eminem’s emergence as one of the most popular rap stars of 2000 raised numerous questions about the evolving meaning of whiteness in U.S. society. Comparing The Slim Shady LP (1999) with his relatively unknown and commercially unsuccessful first album, Infinite (1996), reveals that instead of transcending racial boundaries as some critics have suggested, Eminem negotiated them in ways that made sense to his target audiences. In particular, Eminem’s influential single “My Name Is,” which helped launch his mainstream career, parodied various representations of whiteness to help counter charges that the white rapper lacked authenticity or was simply stealing black culture. -

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” Off the Album Stepfather by People Under the Stairs

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs. Chill, grooving instrumentals. 00:00:05 Oliver Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:07 Morgan Host And I’m Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening to Heat Rocks. Like the rest of you, we are all in our social distancing mode, and this of course is an unprecedented time of isolation and anxiety. And I know many of us, myself included, are turning to art and culture as a way to stay sane and connected and inspired. As such, we wanted to create a few episodes around the idea of comfort music, and we’ve already been engaging with all of you in our audience about it. 00:00:31 Oliver Host To tackle this, we will be using a format that Morgan helped to inspire, the Starting Five, which is both a reference to basketball as well as a nod to those five-CD changers that used to be all the range back in the 1990s. And so both Morgan and I chose five albums, and the last episode you heard her starting five. And today, it’s gonna be my five in terms fo what constitutes my idea of comfort music. 00:00:56 Morgan Host In the third installment, that airs next week, we’ll be choosing a starting five from suggestions that you, our audience, has made via our various social media accounts. So, you asked me and now I’m asking you, what is your definition of comfort music, or what does comfort music really mean to you, especially now? 00:01:15 Oliver Host I really enjoyed hearing what you had to say last week in terms of the albums or the music that reminded you of falling in love wit music, or just falling in love in general. -

Kanyewest Graduation Mp3, Flac, Wma

kanYeWest Graduation mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Graduation Country: UK Released: 2007 Style: Pop Rap, Electro, Conscious MP3 version RAR size: 1880 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1347 mb WMA version RAR size: 1522 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 577 Other Formats: AU MP1 DXD AIFF TTA APE MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Good Morning Engineer [Assistant] – Bram Tobey, Jason Agel, Matty Green , Nate HertweckKeyboards – 1 Andy ChatterleyMixed By – Anthony KilhofferProducer – Kanye WestRecorded By – Andrew 3:15 Dawson, Anthony KilhofferVocals [Additional] – Connie Mitchell, Jay-Z, Tony "Penafire" Williams*Written-By – E. John, B. Taupin*, K. West* Champion Engineer [Assistant] – Andy Marcinkowski, Anthony Palazzole, Bram Tobey, Jason Agel, Nate HertweckLyrics By [Additional Lyrics Added By] – Kanye WestMixed By – Andrew 2 2:47 DawsonProducer – Brian "All Day" Miller, Kanye WestRecorded By – Andrew Dawson, Anthony KilhofferVocals [Additional] – Connie Mitchell, Tony "Penafire" Williams*Written- By – D. Fagen*, W. Becker* Stronger Co-producer [Extended Outro], Recorded By [Extended Outro], Arranged By [Extended Outro] – Mike DeanEngineer [Assistant] – Bram Tobey, Jared Robbins, Jason Agel, Kengo 3 Sakura*, Nate HertweckKeyboards – Andy Chatterley, Omar EdwardsKeyboards, Guitar – 5:11 Mike DeanMixed By – Manny MarroquinProducer – Kanye WestProgrammed By [Additional Programming] – TimbalandRecorded By – Andrew Dawson, Anthony Kilhoffer, Seiji SekineWritten-By – E. Birdsong*, G. De Homen-Christo*, K. West*, T. Banghalter* I Wonder Arranged By [Strings], Conductor [Strings] – Larry GoldBass – Tim ResslerCello – Jennie LorenzoEngineer [Assistant] – Bram Tobey, Dale Parsons, Jason Agel, Nate HertweckKeyboards – Jon BrionMixed By – Andrew DawsonPiano, Synthesizer – Omar 4 4:03 EdwardsProducer – Kanye WestRecorded By – Andrew Dawson, Anthony Kilhoffer, Greg KollerViola – Alexandra Leem, Peter Nocella*Violin – Charles Parker, Emma Kummrow, Gloria Justen, Igor Szwec, Luigi Mazzocchi*, Olga KonopelskyWritten-By – K. -

The Hip-Hop Songs You Didn't Know Were Samples but Really Should

The Hip-Hop Songs You Didn't Know Were Samples But Really Should Hip-hop's relationship with samples is legendary. From its very conception, the genre has looked to loop sections of other tracks and transform them into some of the biggest and most famous hip-hop songs of all time. But sometimes its done so well that you don't even realise it's a sample, so sit back and join us as we look at some of the best hip-hop samples ever. For the best experience, listen to the first track and then check out the sample. (Warning: some of these songs contain strong language that some people may find offensive.) 1) First up, Eminem - 'My Name Is'. Released in 1999, the track set the standard for everything that followed from Eminem, introducing the rapper to the mainstream in an emphatic way. But that iconic bassline is actually a sample. 'My Name Is' samples Labi Siffre's 'I Got The...'. The Hammersmith born soft rock star's 'I Got The' has been sampled by both Jay Z and Eminem, but most famously - and to best effect - by the Detroit rapper. 2) Warren G - 'Regulate' If you were compiling a list of the best hip-hop songs of all time and you missed of 'Regulate', then you just made your first mistake. The 1994 song is rap at its finest, but did you know that the song takes the majority of its structure from a song by Michael McDonald? 'Regulate' samples Michael McDonald's 'I Keep Forgetting'. -

Labi Siffre - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Labi Siffre - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labi_Siffre Labi Siffre From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Labi Siffre (born 25 June 1945) is an English Labi Siffre poet, songwriter, musician and singer most Born 25 June 1945 widely known as the writer and singer of "(Something Inside) So Strong", "It Must Be Hammersmith, London, England Love" and "I Got The", the sampled rhythm Genre(s) R&B, folk, jazz, poetry track which provides the basis for Eminem’s Occupation(s) Poet, musician, writer, breakthrough hit single "My Name Is". singer/songwriter Years active 1970–present Label(s) EMI, Pye Records, China Records, Contents Xavier Books Website Labi Siffre - Into The Light 1 Life and career (http://www.intothelight.info/) 2 Album discography 3 Cover versions 4 Bibliography 4.1 Poetry 4.2 Plays 4.3 Essays 5 References 6 External links Life and career Born the fourth of five children, at Queen Charlotte's Hospital Hammersmith, London to a British (Barbadian / Belgian) mother and a Nigerian father, Siffre was brought up in Bayswater and Hampstead and educated at a Catholic independent day school, St Benedict's School, in Ealing, West London. Jazz and Blues records provided his musical education: Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis and Charles Mingus among many. Jimmy Reed and Wes Montgomery loomed large as guitar influences; Billie Holiday, Jimmy Reed and Mel Tormé as vocal influences. Openly gay,[1] Siffre met his partner, Peter Lloyd, in July 1964. Under the Civil Partnership Act 2004, they became legally recognized partners when the Act entered into force in December 2005.[2] While trying to become a full time musician, Labi worked as a warehouseman in Bethnal Green, a filing clerk at Reuters in Fleet Street and as a minicab driver and delivery man. -

Deep Content-Based Music Recommendation

Deep content-based music recommendation Aaron¨ van den Oord, Sander Dieleman, Benjamin Schrauwen Electronics and Information Systems department (ELIS), Ghent University faaron.vandenoord, sander.dieleman, [email protected] Abstract Automatic music recommendation has become an increasingly relevant problem in recent years, since a lot of music is now sold and consumed digitally. Most recommender systems rely on collaborative filtering. However, this approach suf- fers from the cold start problem: it fails when no usage data is available, so it is not effective for recommending new and unpopular songs. In this paper, we propose to use a latent factor model for recommendation, and predict the latent factors from music audio when they cannot be obtained from usage data. We compare a traditional approach using a bag-of-words representation of the audio signals with deep convolutional neural networks, and evaluate the predictions quantita- tively and qualitatively on the Million Song Dataset. We show that using predicted latent factors produces sensible recommendations, despite the fact that there is a large semantic gap between the characteristics of a song that affect user preference and the corresponding audio signal. We also show that recent advances in deep learning translate very well to the music recommendation setting, with deep con- volutional neural networks significantly outperforming the traditional approach. 1 Introduction In recent years, the music industry has shifted more and more towards digital distribution through online music stores and streaming services such as iTunes, Spotify, Grooveshark and Google Play. As a result, automatic music recommendation has become an increasingly relevant problem: it al- lows listeners to discover new music that matches their tastes, and enables online music stores to target their wares to the right audience. -

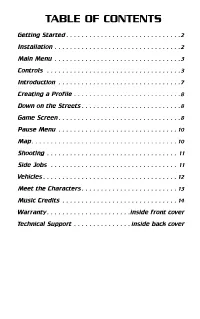

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Getting Started . .2 Installation . .2 Main Menu . .3 Controls . .3 Introduction . .7 Creating a Profile . .8 Down on the Streets . .8 Game Screen . .8 Pause Menu . 10 Map . 10 Shooting . 11 Side Jobs . 11 Vehicles . 12 Meet the Characters . 13 Music Credits . 14 Warranty . .inside front cover Technical Support . inside back cover GETTING STARTED MAIN MENU Double-click on the desktop icon or click once on the icon in the System Requirements Start menu to launch the game. Once the game has finished loading, Supported OS: Windows® XP (SP 1 required)/Vista (only) the Main Menu appears to offer you the following options: Processor: 2.0 GHz Pentium® 4 or AMD Athlon™ (3.4 GHz New Game: Start a new game and create a new profile. recommended) • RAM: 256 MB (512 MB recommended) • Load Profile: Load a profile you have previously saved. Video Card: 64 MB DirectX® 9.0c-compliant supporting Shader • Options: Configure game, video, audio, and control settings. Model 1.1 (128 MB Shader Model 2.0 card recommended) • Credits: View the game credits. (see supported list*) • Quit: Exit the game and return to the desktop. Sound Card: DirectX 9.0c-compliant DirectX Version: DirectX 9.0c (included on disc) DVD-ROM: 4x DVD-ROM or faster CONTROLS Hard Drive Space: 4.8 GB free Peripherals Supported: Windows-compatible keyboard and mouse, The game supports two types of control devices: Xbox 360™ Controller for Windows • Keyboard and mouse *Supported Video Cards at Time of Release • Xbox 360 Controller for Windows ATI® RADEON® 8500/9000/X families NVIDIA® GeForce® 3/4/FX/6/7 families (GeForce 4MX NOT Additional controllers may be supported after release. -

Www .Maver Ic K

MAY/JUNE 2014 www.maverick-country.com MAVERICK FROM THE EDITOR... MEET THE TEAM Welcome to the May/June issue of Maverick Magazine! Editor Laura Bethell I wanted to start by saying that when we as a team produced the March/April issue of Goldings, Elphicks Farm, Water Lane, Maverick Magazine, I couldn’t have been prouder. e moment you see something like that Hunton, Maidstone, Kent, ME15 0SG 01622 823922 come back from press, you know it’s something people will get excited about. It suddenly [email protected] became very real for me and it wasn’t long before all of the wonderful feedback we received Managing Editor started pouring in. I can’t thank you enough for your continued support - this journey has been Michelle Teeman incredible and your feedback will continue to guide the magazine forward, so keep writing in! 01622 823920 [email protected] We are still celebrating the success of the second year of Country2Country Festival in the UK. e event was incredible - the O2 was a great venue for the show and the performances Editorial Assistants Chris Beck this year were second-to-none. ough it was my rst year at the festival, I’d heard a lot of [email protected] progress had been made on last year. e pop-up stages around the O2 bought their own fans, Charlotte Taylor the acts for the main arena bought people in from far and wide. For me, the biggest eye-opener [email protected] was when we stepped inside the arena late on Saturday night to watch last month’s cover stars Project Manager the Zac Brown Band perform. -

AG Song List 1990 to 2018 by Performer

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Performer Title Creator(s) Arranger Performer Month Year Ballad for Kay Nick Webb Acoustic Alchemy May/Jun 1994 Granada Isaac Albeniz Adam del Monte Jul 2001 Queenie's Waltz Adrian Legg Adrian Legg Mar/Apr 1995 I Can't Get My Head Around it Aimee Mann Aimee Mann Jun 2005 It's Not Aimee Mann Aimee Mann Mar 2003 Movin' into the Light Al Anderson, Gary Nicholson Al Anderson Jun 2007 Asia de Cuba Al Di Meola Al Di Meola Sep 2001 Avalon Al Jolson, Buddy DeSylva Al Jolson Feb 2018 Midsummer Moon Al Petteway Al Petteway May 2018 She Moved through the Faire Traditional Al Petteway Dec 2000 Wild Mountain Thyme Traditional Al Petteway Al Petteway Mar 2001 Birds Alberto Lombardi Alberto Lombardi Jan 2018 McCormick Alex de Grassi Alex de Grassi Jun 2012 Mirage Alex de Grassi Alex de Grassi Sep/Oct 1991 The Monkulator Alex de Grassi Alex de Grassi Jun 2013 The Water Garden Alex de Grassi Alex de Grassi Aug 2000 Blue Christmas Billy Hayes, Jay Johnson Alex de Grassi Alex de Grassi Dec 2008 St. James Infirmary Traditional Alex de Grassi Dec 2003 Cinquante Six Ali Farka Toure Ali Farka Toure Mar/Apr 1994 Cinquante Six Ali Farka Toure Ali Farka Toure Aug 1995 Nutshell Layne Stanley, Jerry Cantrell Alice in Chains Oct 2015 Deep Gap Alison Brown Alison Brown Dec 2000 Little Martha Duane Allman Allman Brothers Sep 2018 Melissa Steve Alaimo, Gregg Allman Allman Brothers Band Aug 2007 Horse with No Name Dewey Bunnell America Mar 2011 Up On the Hill Where They Do the Boogie John Hartford Andre DuBrock Sep 2009 Bach and Roll Andrew DuBrock