The United States Senate: a 50-50 Split?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background of Pennsylvania Government

Background of Pennsylvania Government The Pennsylvania General Assembly In 1776, the Pennsylvania Legislature was established as a lawmaking body by the first state constitution. Originally unicameral, the General Assembly became bicameral under the second constitution of 1790 and since that time has been comprised of a House of Representatives and a Senate. The General Assembly meets in two-year sessions. House and Senate legislative districts are reapportioned every 10 years after the federal census is taken. Reapportionment following the 2000 census created state House districts of approximately 59,000 people and Senate districts of about 240,000 people. There are 203 members in the House of Representatives; a number established when the state's constitution was revised in 1967. A representative must be at least 21 years of age, a resident of the commonwealth for four years and a resident of the district for at least one year. The term of office for a member of the House is two years, with all seats up for re-election at the same time. When the Senate was first established in 1790, there were only 18 senators. Following the 1874 Constitutional Convention, that number was increased to 50, where it remains today. A senator must be at least 25 years of age with the same residency requirements as members of the House. Senate terms are four years, with odd- and even-numbered district seats contested on a rotating basis. Chamber and caucus leadership The principal officers of the state Senate are the president pro tempore, the secretary and the chief clerk, all of whom are elected by the Senate. -

The 2020 Presidential Election: Provisions of the Constitution and U.S. Code

PREFACE The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is proud to acknowledge its role in the Presidential election pro- cess. NARA’s Office of the Federal Register (OFR) acts as the administrator of the Electoral College and carries out the duties of the Archivist. In this role, the OFR is charged with helping the States carry out their election responsibilities, ensuring the completeness and integrity of the Electoral College documents submitted to Congress, and informing the public about the Presidential election process. The Electoral College system was established under Article II and Amendment 12 of the U.S. Constitution. In each State, the voters choose electors to select the President and Vice President of the United States, based on the results of the Novem- ber general election. Before the general election, the Archivist officially notifies each State’s governor and the Mayor of the District of Columbia of their electoral responsibilities. OFR provides instructions and resources to help the States and District of Columbia carry out those responsibilities. As the results of the popular vote are finalized in each state, election officials create Certificates of Ascertainment, which establish the credentials of their electors, that are sent to OFR. In December, the electors hold meetings in their States to vote for President and Vice President. The electors seal Certificates of Vote and send them to the OFR and Congress. In January, Congress sits in joint session to certify the election of the President and Vice President. In the year after the election, electoral documents are held at the OFR for public viewing, and then transferred to the Archives of the United States for permanent retention and access. -

How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed

Idaho Law Review Volume 50 | Number 3 Article 1 October 2014 How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review Recommended Citation Scott .W Reed, How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits, 50 Idaho L. Rev. 1 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review/vol50/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Idaho Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW AND WHY IDAHO TERMINATED TERM LIMITS SCOTT W. REED1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 II. THE 1994 INITIATIVE ...................................................................... 2 A. Origin of Initiatives for Term Limits ......................................... 3 III. THE TERM LIMITS HAVE POPULAR APPEAL ........................... 5 A. Term Limits are a Conservative Movement ............................. 6 IV. TERM LIMITS VIOLATE FOUR STATE CONSTITUTIONS ....... 7 A. Massachusetts ............................................................................. 8 B. Washington ................................................................................. 9 C. Wyoming ...................................................................................... 9 D. Oregon ...................................................................................... -

Ebonics Hearing

S. HRG. 105±20 EBONICS HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SPECIAL HEARING Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39±641 cc WASHINGTON : 1997 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi TOM HARKIN, Iowa SLADE GORTON, Washington ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina HARRY REID, Nevada LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho HERB KOHL, Wisconsin KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas PATTY MURRAY, Washington Majority Professional Staff CRAIG A. HIGGINS and BETTILOU TAYLOR Minority Professional Staff MARSHA SIMON (II) 2 CONTENTS Page Opening remarks of Senator Arlen Specter .......................................................... -

I~N~ 2 4I~ 7~~ 4~II 888 ~I ~I ~II C - ~~9 ~~ 6 I~II C ~~I E CONSTITUTION of THE

Date Printed: 01/14/2009 JTS Box Number: IFES 27 Tab Number: 25 Document Title: CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS Document Date: 1998 Document Country: FIJ Document Language: ENG. IFES ID: CON00070 *I~n~ 2 4 I~ 7 ~~ 4 ~II 888 ~I ~I ~II C - ~~9 ~~ 6 I~II C ~~I E CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS 27th July 1998 I CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS CONTENTS PREAMBLE CHAPTER I-THE STATE I. The Republic of the Fiji Islands 2. Supremacy of Constitution 3. Interpretation of Constitution 4. Languages 5. State and religion CHAPTER 2-COMPACT 6. Compact 7. Application of Compact CHAPTER 3-CITIZENSHIP 8. Retention of eXisting citizenship 9. Way in which citizenship may be acquired 10. Citizenship by birth II. Infant found abandoned in the Fiji Islands 12. Citizer.ship by registration 13. Citizenship by naturalisation 14. Loss of citizenship 15. Renunciation of citizenship 16. Rights to enter and reside in the Fiji Islands 17. Powers of Parliament concerning citizenship 18. Laws relating to calculation of periods in the Fiji Islands 19. Deprivation of citizenship 20. Prevention of statelessness CHAPTER 4-D1LL OF RIGHTS 21. Application 22. Life 23. Personal liberty 24. Freedom from servitude and forced labour 25. Freedom from cruel or degrading treatment 1 F Clifton Wl:ii~ Resource Center flit; International Found'

REGULATION on the Joint Meetings of the Chamber of Deputies and of the Senate of Romania Regulation on the Joint Meetings Of

REGULATION on the Joint Meetings of the Chamber of Deputies and of the Senate of Romania Regulation on the Joint Meetings of the Chamber of Deputies and of the Senate, approved by the Decision of the Parliament of Romania No 4 of 3 March 1992, published in the Official Journal of Romania, Part I, No 34 of 4 March 1992, as amended and completed by the Decision of the Parliament No 13/1995, published in the Official Journal of Romania, Part I, No 136 of 5 July 1995. CHAPTER I Organisation and Running of the Joint Meetings Section 1 Competence; Convening of the Joint Meetings Article 1 - The Chamber of Deputies and the Senate shall meet in joint meetings in order: 1. to received the message of the President of Romania (Article 62 (2) (a) of the Constitution); 2. to approve the State Budget and the State social security budget (Article 62 (2)(b) of the Constitution), the corrections and the account for budget implementation; 3. to declare general or partial mobilization (Article 62 (2) (c) of the Constitution); 4. to declare a state of war (Article 62 (2) (d) of the Constitution); 5. to suspend or terminate armed hostilities (Article 62 (2) (e) of the Constitution); 6. to examine reports of the Supreme Council of National Defence and of the Court of Audit (Article 62 (2) (f) of the Constitution); 7. to appoint, upon the proposal of the President of Romania, the Director of the Romanian Intelligence Service, and to exercise control over the activity of this Service (Article 62 (2) (g) of the Constitution); 8. -

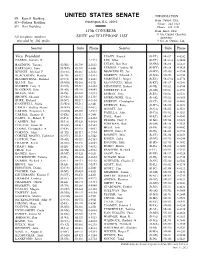

Senators Phone List.Pdf

UNITED STATES SENATE INFORMATION SR—Russell Building From Outside Dial: Washington, D.C. 20510 SD—Dirksen Building Senate—224–3121 SH—Hart Building House—225–3121 117th CONGRESS From Inside Dial: 0 for Capitol Operator All telephone numbers SUITE and TELEPHONE LIST Assistance preceded by 202 prefix 9 for an Outside Line Senator Suite Phone Senator Suite Phone Vice President LEAHY, Patrick (D-VT) SR-437 4-4242 HARRIS, Kamala D. 4-2424 LEE, Mike (R-UT) SR-361A 4-5444 BALDWIN, Tammy (D-WI) SH-709 4-5653 LUJAN, Ben Ray (D-NM) SR-498 4-6621 BARRASSO, John (R-WY) SD-307 4-6441 LUMMIS, Cynthia M. (R-WY) SR-124 4-3424 BENNET, Michael F. (D-CO) SR-261 4-5852 MANCHIN III, Joe (D-WV) SH-306 4-3954 BLACKBURN, Marsha (R-TN) SD-357 4-3344 MARKEY, Edward J. (D-MA) SD-255 4-2742 BLUMENTHAL, Richard (D-CT) SH-706 4-2823 MARSHALL, Roger (R-KS) SR-479A 4-4774 BLUNT, Roy (R-MO) SR-260 4-5721 McCONNELL, Mitch (R-KY) SR-317 4-2541 BOOKER, Cory A. (D-NJ) SH-717 4-3224 MENENDEZ, Robert (D-NJ) SH-528 4-4744 BOOZMAN, John (R-AR) SH-141 4-4843 MERKLEY, Jeff (D-OR) SH-531 4-3753 BRAUN, Mike (R-IN) SR-404 4-4814 MORAN, Jerry (R-KS) SD-521 4-6521 BROWN, Sherrod (D-OH) SH-503 4-2315 MURKOWSKI, Lisa (R-AK) SH-522 4-6665 BURR, Richard (R-NC) SR-217 4-3154 MURPHY, Christopher (D-CT) SH-136 4-4041 CANTWELL, Maria (D-WA) SH-511 4-3441 MURRAY, Patty (D-WA) SR-154 4-2621 CAPITO, Shelley Moore (R-WV) SR-172 4-6472 OSSOFF, Jon (D-GA) SR-455 4-3521 CARDIN, Benjamin L. -

THE PRESIDENT's REORGANIZATION AUTHORITY 1 !"%., D)

U.S. GENERAL ACCOUNTING OFFICE Washington, D.C. FOR RELEASE ON DELIVERY Expected at 11:OO a.m. May 6, 1981 STATEMENT OF MILTON J. SOCOLAR 1 115307I ACTING COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES BEFORE TBE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ON . .._.I I’ --- I/ THE PRESIDENT'S REORGANIZATION AUTHORITY 1 !"%.,_ d) Mr. Chairman, we are pleased to appear today to discuss the subject of Presidential reorganization authority. I am including as appendix I the digest of our recent report on the Reorganization Act of 1977. In reviewing several reorgani- zations, we identified what seems to be a fundamental problem in the reorganization process. Substantial time and resources are always devoted to deciding what is to be reorganized; little at- tention is given, however, to planning the mechanics of how re- organizations are to be implemented. The lack of early implementation planning results in substan- tial startup problems distracting agency officials from their new missions during the critical first year of operations. Also, with- out implementation data, the Congress is not aware of the full impact of reorganization requirements. Ten reorganization plans were carried out under the Reorgani- zation Act of 1977. We reviewed four affecting six agencies: the Civil Service Commission (relating to the Federal Labor Relations Authority, the Merit Systems Protection Board, and the Office of the Special Counsel), the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the International Development Cooperation Agency. Startup problems at the six new and reorganized agencies were severe. It took from 10 to 23 months to obtain key officials at two of the agencies. -

The Belgian Federal Parliament

The Belgian Federal Parliament Welcome to the Palace of the Nation PUBLISHED BY The Belgian House of Representatives and Senate EDITED BY The House Department of Public Relations The Senate Department of Protocol, Reception & Communications PICTURES Guy Goossens, Kevin Oeyen, Kurt Van den Bossche and Inge Verhelst, KIK-IRPA LAYOUT AND PRINTING The central printing offi ce of the House of Representatives July 2019 The Federal Parliament The Belgian House of Representatives and Senate PUBLISHED BY The Belgian House of Representatives and Senate EDITED BY The House Department of Public Relations The Senate Department of Protocol, Reception & Communications PICTURES This guide contains a concise description of the workings Guy Goossens, Kevin Oeyen, Kurt Van den Bossche and Inge Verhelst, KIK-IRPA of the House of Representatives and the Senate, LAYOUT AND PRINTING and the rooms that you will be visiting. The central printing offi ce of the House of Representatives The numbers shown in the margins refer to points of interest July 2019 that you will see on the tour. INTRODUCTION The Palace of the Nation is the seat of the federal parliament. It is composed of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. The House and the Senate differ in terms of their composition and competences. 150 representatives elected by direct universal suffrage sit in the House of Representatives. The Senate has 60 members. 50 senators are appointed by the regional and community parliaments, and 10 senators are co-opted. The House of Representatives and the Senate are above all legislators. They make laws. The House is competent for laws of every kind. -

Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress: Perspectives and Contemporary Analysis

Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress: Perspectives and Contemporary Analysis Updated October 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R40504 Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress Summary The 12th Amendment to the Constitution requires that presidential and vice presidential candidates gain “a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed” in order to win election. With a total of 538 electors representing the 50 states and the District of Columbia, 270 electoral votes is the “magic number,” the arithmetic majority necessary to win the presidency. What would happen if no candidate won a majority of electoral votes? In these circumstances, the 12th Amendment also provides that the House of Representatives would elect the President, and the Senate would elect the Vice President, in a procedure known as “contingent election.” Contingent election has been implemented twice in the nation’s history under the 12th Amendment: first, to elect the President in 1825, and second, the Vice President in 1837. In a contingent election, the House would choose among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes. Each state, regardless of population, casts a single vote for President in a contingent election. Representatives of states with two or more Representatives would therefore need to conduct an internal poll within their state delegation to decide which candidate would receive the state’s single vote. A majority of state votes, 26 or more, is required to elect, and the House must vote “immediately” and “by ballot.” Additional precedents exist from 1825, but they would not be binding on the House in a contemporary election. -

Counting Electoral Votes: an Overview of Procedures at the Joint Session, Including Objections by Members of Congress

Counting Electoral Votes: An Overview of Procedures at the Joint Session, Including Objections by Members of Congress Updated December 8, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32717 Counting Electoral Votes: An Overview of Procedures at the Joint Session, Including Objections by Members of Congress Summary The Constitution and federal law establish a detailed timetable following the presidential election during which time the members of the electoral college convene in the 50 state capitals and in the District of Columbia, cast their votes for President and Vice President, and submit their votes through state officials to both houses of Congress. The electoral votes are scheduled to be opened before a joint session of Congress on January 6, 2021. Federal law specifies the procedures for this session and for challenges to the validity of an electoral vote. This report describes the steps in the process and precedents set in prior presidential elections governing the actions of the House and Senate in certifying the electoral vote and in responding to challenges of the validity of electoral votes. This report has been revised and will be updated on a periodic basis to provide the dates for the relevant joint session of Congress and to reflect any new, relevant precedents or practices. Congressional Research Service Counting Electoral Votes: An Overview of Procedures at the Joint Session, Including Objections by Members of Congress Contents Actions Leading Up to the Joint Session ........................................................................................ -

Fiji Promulgations and Decrees

Constitution of the Sovereign Democratic Republic of Fiji (Pro... http://www.paclii.org/fj/promu/promu_dec/cotsdrofd1990712/ Home | Databases | WorldLII | Search | Feedback Fiji Promulgations and Decrees You are here: PacLII >> Databases >> Fiji Promulgations and Decrees >> Constitution of the Sovereign Democratic Republic of Fiji (Promulgation) Decree 1990 Database Search | Name Search | Noteup | Download | Help Download original PDF Constitution of the Sovereign Democratic Republic of Fiji (Promulgation) Decree 1990 REPUBLIC OF FIJI DECREE NO. 22 ______ CONSTITUTION OF THE SOVEREIGN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF FIJI (PROMULGATION) DECREE 1990 _______ WHEREAS by Order in Council made the 20th day of September 1970 Her Majesty the Queen established a Constitution for Fiji (the 1970 Constitution); AND WHEREAS events in 1987 in Fiji led to the abrogation of the 1970 Constitution; AND WHEREAS Fiji was declared a Republic on the 7th day of October, 1987 and the first President of the Republic of Fiji was appointed under Section 4 of the Appointment of Head of State and Dissolution of Fiji Military Government Decree, on the 5th day of December, 1987 who, until a Parliament is convened in accordance with a Constitution yet to be adopted- (i) shall have the power to appoint the Prime Minister by Decree; (ii) shall have the power to make laws for the peace, order and good government of Fiji by Decree, acting in accordance with the advice of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet; and (iii) shall exercise the executive authority of Fiji which is hereby vested in him; save as otherwise provided, that executive authority may be exercised in accordance with the advice of the Cabinet or by any Minister authorised by the Cabinet; AND WHEREAS the first President of the Republic of Fiji had appointed Ratu Sir Kamisese Kapaiwai Tuimacilai Mara, G.C.M.G.; K.B.E.; Kt SJ as the first Prime Minister of the Republic of Fiji under the 1 of 64 8/21/12 4:54 PM Constitution of the Sovereign Democratic Republic of Fiji (Pro..