THE PRESIDENT's REORGANIZATION AUTHORITY 1 !"%., D)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed

Idaho Law Review Volume 50 | Number 3 Article 1 October 2014 How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review Recommended Citation Scott .W Reed, How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits, 50 Idaho L. Rev. 1 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review/vol50/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Idaho Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW AND WHY IDAHO TERMINATED TERM LIMITS SCOTT W. REED1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 II. THE 1994 INITIATIVE ...................................................................... 2 A. Origin of Initiatives for Term Limits ......................................... 3 III. THE TERM LIMITS HAVE POPULAR APPEAL ........................... 5 A. Term Limits are a Conservative Movement ............................. 6 IV. TERM LIMITS VIOLATE FOUR STATE CONSTITUTIONS ....... 7 A. Massachusetts ............................................................................. 8 B. Washington ................................................................................. 9 C. Wyoming ...................................................................................... 9 D. Oregon ...................................................................................... -

Ebonics Hearing

S. HRG. 105±20 EBONICS HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SPECIAL HEARING Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39±641 cc WASHINGTON : 1997 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi TOM HARKIN, Iowa SLADE GORTON, Washington ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina HARRY REID, Nevada LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho HERB KOHL, Wisconsin KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas PATTY MURRAY, Washington Majority Professional Staff CRAIG A. HIGGINS and BETTILOU TAYLOR Minority Professional Staff MARSHA SIMON (II) 2 CONTENTS Page Opening remarks of Senator Arlen Specter .......................................................... -

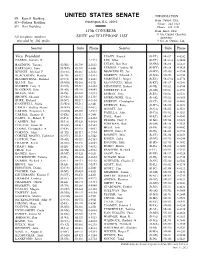

Senators Phone List.Pdf

UNITED STATES SENATE INFORMATION SR—Russell Building From Outside Dial: Washington, D.C. 20510 SD—Dirksen Building Senate—224–3121 SH—Hart Building House—225–3121 117th CONGRESS From Inside Dial: 0 for Capitol Operator All telephone numbers SUITE and TELEPHONE LIST Assistance preceded by 202 prefix 9 for an Outside Line Senator Suite Phone Senator Suite Phone Vice President LEAHY, Patrick (D-VT) SR-437 4-4242 HARRIS, Kamala D. 4-2424 LEE, Mike (R-UT) SR-361A 4-5444 BALDWIN, Tammy (D-WI) SH-709 4-5653 LUJAN, Ben Ray (D-NM) SR-498 4-6621 BARRASSO, John (R-WY) SD-307 4-6441 LUMMIS, Cynthia M. (R-WY) SR-124 4-3424 BENNET, Michael F. (D-CO) SR-261 4-5852 MANCHIN III, Joe (D-WV) SH-306 4-3954 BLACKBURN, Marsha (R-TN) SD-357 4-3344 MARKEY, Edward J. (D-MA) SD-255 4-2742 BLUMENTHAL, Richard (D-CT) SH-706 4-2823 MARSHALL, Roger (R-KS) SR-479A 4-4774 BLUNT, Roy (R-MO) SR-260 4-5721 McCONNELL, Mitch (R-KY) SR-317 4-2541 BOOKER, Cory A. (D-NJ) SH-717 4-3224 MENENDEZ, Robert (D-NJ) SH-528 4-4744 BOOZMAN, John (R-AR) SH-141 4-4843 MERKLEY, Jeff (D-OR) SH-531 4-3753 BRAUN, Mike (R-IN) SR-404 4-4814 MORAN, Jerry (R-KS) SD-521 4-6521 BROWN, Sherrod (D-OH) SH-503 4-2315 MURKOWSKI, Lisa (R-AK) SH-522 4-6665 BURR, Richard (R-NC) SR-217 4-3154 MURPHY, Christopher (D-CT) SH-136 4-4041 CANTWELL, Maria (D-WA) SH-511 4-3441 MURRAY, Patty (D-WA) SR-154 4-2621 CAPITO, Shelley Moore (R-WV) SR-172 4-6472 OSSOFF, Jon (D-GA) SR-455 4-3521 CARDIN, Benjamin L. -

Brief of 47 Members of the United States Senate As Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Nos. 19-840 & 19-1019 IN THE CALIFORNIA, ET AL., Petitioners / Cross-Respondents, v. TEXAS, ET AL., Respondents / Cross-Petitioners. On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit BRIEF OF 47 MEMBERS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS ADAM S. GERSHENSON ELIZABETH B. PRELOGAR ELIZABETH A. TRAFTON Counsel of Record COOLEY LLP COOLEY LLP 500 Boylston Street 1299 Pennsylvania Ave., NW Boston, MA 02116 Washington, DC 20004 (202) 842-7800 SAMANTHA A. KIRBY [email protected] COOLEY LLP 3175 Hanover Street Palo Alto, CA 94304 NATALIE D. VERNON COOLEY LLP 101 California Street San Francisco, CA 94111 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATEMENT OF INTEREST ..................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 3 I. SECTION 5000A IS SEVERABLE FROM THE REST OF THE ACA. ................................ 4 A. A Straightforward Application Of Severability Principles Demonstrates Section 5000A Is Severable. ..................... 5 B. Respondents’ Arguments Against Severability Are Unavailing. .................. 14 II. CONGRESS DID NOT INTEND THE DISASTROUS CONSEQUENCES THAT WOULD FLOW FROM REPEAL OF THE ACA. ............................................................... 18 A. Invalidating the ACA Would Leave Millions Uninsured and Millions More with Lower Quality Coverage. ...... 19 B. Invalidating the ACA Would Inject Chaos into the Health Care Market and Impose Substantial Costs. ................ 21 C. Invalidating the ACA Would Disproportionately Harm Americans Who Already Face Barriers to Care. ....... 25 D. Invalidating the ACA Would Nullify Congress’s Informed Policy Decision. ............................................... 29 CONCLUSION .......................................................... 30 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Alaska Airlines, Inc. v. Brock, 480 U.S. 678 (1987) ........................................ 5, 6, 7, 8 Ayotte v. -

Federal Government

Federal Government US Capitol Building Photo courtesy of Architect of the Capitol Congressional Districts 46 IDAHO BLUE BOOK U.S. Congress Article I of the U.S. Constitution states agencies to determine if they are following that, “All legislative Powers herein granted government policy, and may introduce new shall be vested in a Congress of the United legislation based on what they discover. States, which shall consist of a Senate and Bills accepted by both houses of Con- a House of Representatives.” This bicam- gress and by the President become law. eral legislature (a governing body with two However, the President may veto a bill and houses) is the primary lawmaking body in return it to Congress. Congress then reviews the U.S. government. To solve problems, the reasons for the rejection but may still Federal Members of Congress introduce legislative act to pass the bill. The U.S. Constitution proposals called bills or resolutions. After allows Congress to override the President’s considering these proposals Members vote veto with a two-thirds majority vote of both to adopt or to reject them. Members of the House and the Senate. Congress also review the work of executive Members of Congress Members of the Senate and of the House elected for a period of six years, while of Representatives are known respectively representatives are elected for a period as senators and representatives. Each of two years. Furthermore, senators and Member of Congress is elected by representatives must meet the following receiving the greatest number of votes minimum requirements: in the general election. -

114Th Congress 83

HAWAII 114th Congress 83 HAWAII (Population 2010, 1,360,301) SENATORS BRIAN SCHATZ, Democrat, of Hawaii; born in Ann Arbor, MI, October 20, 1972; education: graduated from Punahou School, Honolulu, HI, 1990; B.A., Pomona College, Clare- mont, CA, 1994; professional: chairman, Democratic Party of Hawaii, 2008–10; CEO, Helping Hands Hawaii, 2002–10; Hawaii House of Representatives, 1998–2006; Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii, 2010–12; married: Linda Schatz; committees: Appropriations; Commerce, Science, and Transportation; Indian Affairs; Select Committee on Ethics; appointed to the United States Sen- ate on December 26, 2012, and took the oath of office on December 27, 2012. Office Listings http://www.schatz.senate.gov twitter: @senbrianschatz https://www.facebook.com/senbrianschatz 722 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 ....................................................... (202) 224–3934 Chief of Staff.—Andrew Winer. FAX: 228–1153 Scheduler.—Diane Miyasato. Legislative Director.—Arun Revana. Communications Director.—Karen Lightfoot. 300 Ala Moana Boulevard, Room 7–212, Honolulu, HI 96850 ............................................... (808) 523–2061 FAX: 523–2065 *** MAZIE HIRONO, Democrat, of Hawaii; born in Fukushima, Japan, November 3, 1947; grad- uated from Kaimuki High School, Honolulu, HI; B.A., University of Hawaii, Manoa, HI, 1970; J.D., Georgetown University, Washington, DC, 1978; professional: lawyer, private practice; member of the Hawaii State House of Representatives, 1981–94; Hawaii Lieutenant Governor, 1994–2002; elected to the United States House of Representatives as a Democrat to the 110th, 111th, and 112th Congresses; was not a candidate for reelection to the United States House of Representatives for the 113th Congress; committees: Armed Services; Energy and Natural Resources; Small Business; Veterans’ Affairs; Select Committee on Intelligence; elected to the United States Senate on November 6, 2012. -

The Changing Face of the Congressional Black Caucus

THE CHANGING FACE OF THE CONGRESSIONAL BLACK CAUCUS KAREEM CRAYTON I. INTRODUCTION In March of 2007, Congressman John Lewis faced a problem of a metaphysical variety. Try as he might, he simply could not be present in two places at once. The setting was Selma, Alabama, during the series of ceremonies commemorating the 1965 march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday.1 About four decades earlier, a much younger John Lewis (then, a spokesman for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) had been assaulted and beaten by a phalanx of Alabama state police while leading a march protesting the state’s denial of the ballot to black citizens.2 That moment in time secured Lewis’s place in American history and politics as a hero of the civil rights movement, and it later made him the easy favorite to win a Congressional seat representing the city of Atlanta, Georgia.3 Among the country’s best-known black political leaders, Congressman Lewis was a prime catch for any politician who was lucky enough to appear with him during the march. Evidence of even a tacit endorsement from him would have been an appealing prize for any of the Democratic presidential hopefuls, all of whom were heavily courting black voters in the South’s primary states. With so much press attention on his whereabouts during the Selma ceremonies, Lewis was quite publicly torn about where to fit in. In an extended radio interview on the topic, Lewis described his deep ambivalence about which candidate would ultimately receive his support.4 Associate Professor of Law & Political Science, University of Southern California. -

Minutes of the Senate Democratic Conference

MINUTES OF THE SENATE DEMOCRATIC CONFERENCE 1903±1964 MINUTES OF THE SENATE DEMOCRATIC CONFERENCE Fifty-eighth Congress through Eighty-eighth Congress 1903±1964 Edited by Donald A. Ritchie U.S. Senate Historical Office Prepared under the direction of the Secretary of the Senate U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 105th Congress S. Doc. 105±20 U.S. Government Printing Office Washington: 1998 Cover illustration: The Senate Caucus Room, where the Democratic Conference often met early in the twentieth century. Senate Historical Office. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senate Democratic Conference (U.S.) Minutes of the Senate Democratic Conference : Fifty-eighth Congress through Eighty-eighth Congress, 1903±1964 / edited by Donald A. Ritchie ; prepared under the direction of the Secretary of the Senate. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. United States. Congress. SenateÐHistoryÐ20th centuryÐSources. 2. Democratic Party (U.S.)ÐHistoryÐ20th centuryÐSources. I. Ritchie, Donald A., 1945± . II. United States. Congress. Senate. Office of the Secretary. III. Title. JK1161.S445 1999 328.73'07657Ðdc21 98±42670 CIP iv CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................................................... xiii Preface .......................................................................................... xv Introduction ................................................................................. xvii 58th Congress (1903±1905) March 16, 1903 .................................................................... -

Transcript Vice President Hubert Humphrey

TRANSCRIPT VICE PRESIDENT H U BERT HUMPHREY Haw aii Pre p A c ade my - Augu,st 5, 196 7 Hilo Big Islanders. We gather here this evening at the Hawaii Preparatory Field House to honor certainly one of Hawaii's finest friends from Washington, certainly an individual that all of us claim as a resident of Hawaii. At this time before we begin the invocation by Rev. Boshard I would like to introduce very briefly the individuals seated at the head table. Representing the Governor,State of Hawaii, Mr. & Mrs. Kenneth Brown. (CLAP) Our Congressman in l"ashington, Congressman Spark M. MatsuP.aga and Mrs. Helene Matsunaga. (CLAP) I understand tomorrow is their second honeymoon and their 25th anniversary. (CLAP) At this time, I would like to introduce Mr. Henry Giugni, the personal representative of Senator Daniel K. Inouye. Mr. Henry Giugni. (CLAP) Our Democratic National Committee Woman, Representative Momi Minn. (CLAP) And members of the traveling party of the distinguished guest, Dr. & Mrs. Edgar Berman, Mr. & Mrs. Duane Andreas, Mr. Pat O'Connor. Our distinguished guest's Aide and Mrs. Gartner. Mr. & Mrs. David Gartner. Mr. & Mrs. Richard Polack, the Assistant Editor of the Honolulu Star Bulletin. The charming daughter of the Vice President and Mrs. Humphrey, Mrs. Nancy Solomonson. Last night the Vice President claimed for Hawaii the third Senator and the third Congresswoman, Mrs. Hubert Humphrey. Mrs. Hubert Humphrey . Ladies and Gentlemen, our kamaaina, the Vice President of the United States, Mr. Hubert Humphrey. At this time, I would like to call on the Rev. Henry Boshard of the Mokuaikaua Church of Kailua, Kona for the invocation. -

Cheri Beasley Endorsement

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 28, 2021 Contact: Yolonda Addison [email protected] Contact: Kelley Jackson [email protected] Contact: Aprill Turner [email protected] CONGRESSIONAL BLACK CAUCUS PAC, DEMOCRACY FOR AMERICA PAC, HIGHER HEIGHTS FOR AMERICA PAC Announce Their Joint Endorsement of Former Chief Justice Cheri Beasley in her Bid for U.S. Senate The CBCPAC, DFA PAC, HHFA PAC proudly endorse Fmr Chief Justice Beasley in her U.S. Senate run in North Carolina. Washington, D.C. - The Congressional Black Caucus PAC (the political arm of the Congressional Black Caucus), Democracy for America PAC (the people-powered, grassroots organization), and Higher Heights for America PAC (the only organization in the U.S. whose sole purpose is to elect African American Women to higher office) announced their joint endorsement of Former Chief Justice Cheri Beasley in her bid for the U.S. Senate. “It is crucial for our hard working Members in the House of Representatives to have colleagues in the Senate to ensure that their amazing bills become laws. We have seen what happens when we don’t have Senators who share our values and make it their mission to stall legislation. The CBCPAC is honored to endorse Justice Cheri Beasley to become the next US Senator from North Carolina,” CBCPAC Executive Director, Yolonda Addison said. “Cheri Beasley is no stranger to fighting uphill battles and delivering on her promises for North Carolina families; that’s why Democracy for America is excited to endorse her campaign for the U.S. Senate in North Carolina. We’re confident that Cheri is ready to take on special interests and go to Washington to create change for those that have been left behind for far too long. -

Traditions of the United States Senate Cover: the Senator from Massachusetts Interrupts, William A

TRADITIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE Cover: The Senator from Massachusetts Interrupts, William A. Rogers, Harper’s Weekly, April 10, 1897. The author extends his deepest appreciation to Emily J. Reynolds, Mary Suit Jones, Diane K. Skvarla, and David J. Tinsley for their careful reading and experience-based suggestions. Thanks also to Senate Historical Editor Beth Hahn, Senate Photo Historian Heather Moore, and Printing and Document Services Director Karen Moore. Additional copies available through the Senate Office of Printing and Document Services, Room SH–B04. TRADITIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE Richard A. Baker Senate Historian Prepared under the direction of Nancy Erickson Secretary of the Senate Contents BECOMING A SENATOR . 2 • Orientation programs • Oath taking • Members’ order-of-service numbers • “Father of the Senate” • Seniority • Senate Bean Soup ON THE SENATE FLOOR . 6 • Senate officers • Senate desks • Maiden speeches • Senate pages • Official photograph • Candy desk • Seersucker Thursday SENATE FLOOR PROCEEDINGS . 14 • Chaplain’s prayer • Pledge of Allegiance • Senate gavels • Decorum • “Golden Gavel” Award • Floor leaders’ right of priority recognition • Honoring distinguished visitors • Presentation of messages SENATE LEGACIES . 20 • Naming of buildings and rooms • Vice-presidential busts • Senate Reception Room’s “Famous Nine” • Old Senate Chamber • Washington’s Farewell Address • Senate spouses’ organization • End-of-session valedictories and eulogies • Funerals and memorial services “CITADEL OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND DEMOCRATIC LIBERTIES” . 28 TRADITIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE TRADITIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE At a few yards’ distance [from the Chamber early years of the Senate’s “Golden Age,” of the House of Representatives] is the door helped to promote that notion. -

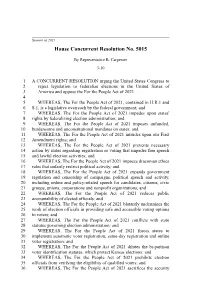

House Concurrent Resolution No. 5015

Session of 2021 House Concurrent Resolution No. 5015 By Representative B. Carpenter 3-10 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION urging the United States Congress to 2 reject legislation to federalize elections in the United States of 3 America and oppose the For the People Act of 2021. 4 5 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021, contained in H.R.1 and 6 S.1, is a legislative overreach by the federal government; and 7 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021 impedes upon states' 8 rights by federalizing election administration; and 9 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021 imposes unfunded, 10 burdensome and unconstitutional mandates on states; and 11 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021 intrudes upon our First 12 Amendment rights; and 13 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021 prevents necessary 14 action by states regarding registration or voting that impedes free speech 15 and lawful election activities; and 16 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021 imposes draconian ethics 17 rules that unfairly restrict political activity; and 18 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021 expands government 19 regulation and censorship of campaigns, political speech and activity, 20 including online and policy-related speech for candidates, citizens, civic 21 groups, unions, corporations and nonprofit organizations; and 22 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021 reduces public 23 accountability of elected officials; and 24 WHEREAS, The For the People Act of 2021 blatantly undermines the 25 work of election officials in providing safe and accessible voting options