The Changing Face of the Congressional Black Caucus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Directory ALABAMA

2 Congressional Directory ALABAMA ALABAMA (Population 2000, 4,447,100) SENATORS RICHARD C. SHELBY, Republican, of Tuscaloosa, AL; born in Birmingham, AL, May 6, 1934; education: attended the public schools; A.B., University of Alabama, 1957; LL.B., University of Alabama School of Law, 1963; professional: attorney; admitted to the Alabama bar in 1961 and commenced practice in Tuscaloosa; member, Alabama State Senate, 1970–78; law clerk, Supreme Court of Alabama, 1961–62; city prosecutor, Tuscaloosa, 1963–71; U.S. Commissioner, Northern District of Alabama, 1966–70; special assistant Attorney General, State of Alabama, 1968–70; chairman, legislative council of the Alabama Legislature, 1977–78; former president, Tuscaloosa County Mental Health Association; member of Alabama Code Revision Committee, 1971–75; member: Phi Alpha Delta legal fraternity, Tuscaloosa County; Alabama and American bar associations; First Presbyterian Church of Tuscaloosa; Exchange Club; American Judicature Society; Alabama Law Institute; married: the former Annette Nevin in 1960; children: Richard C., Jr. and Claude Nevin; committees: Appropriations; chairman, Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Special Committee on Aging; elected to the 96th Congress on November 7, 1978; reelected to the three succeeding Congresses; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 1986; reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings http://shelby.senate.gov 110 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 ......................................... (202) 224–5744 Administrative Assistant.—Louis Tucker. FAX: 224–3416 Personal Secretary / Appointments.—Anne Caldwell. Press Secretary.—Virginia Davis. P.O. Box 2570, Tuscaloosa, AL 35403 ........................................................................ (205) 759–5047 Federal Building, Room 321, 1800 5th Avenue North, Birmingham, AL 35203 ...... (205) 731–1384 308 U.S. -

How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed

Idaho Law Review Volume 50 | Number 3 Article 1 October 2014 How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits Scott .W Reed Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review Recommended Citation Scott .W Reed, How and Why Idaho Terminated Term Limits, 50 Idaho L. Rev. 1 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review/vol50/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Idaho Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW AND WHY IDAHO TERMINATED TERM LIMITS SCOTT W. REED1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 II. THE 1994 INITIATIVE ...................................................................... 2 A. Origin of Initiatives for Term Limits ......................................... 3 III. THE TERM LIMITS HAVE POPULAR APPEAL ........................... 5 A. Term Limits are a Conservative Movement ............................. 6 IV. TERM LIMITS VIOLATE FOUR STATE CONSTITUTIONS ....... 7 A. Massachusetts ............................................................................. 8 B. Washington ................................................................................. 9 C. Wyoming ...................................................................................... 9 D. Oregon ...................................................................................... -

Ebonics Hearing

S. HRG. 105±20 EBONICS HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SPECIAL HEARING Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39±641 cc WASHINGTON : 1997 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi TOM HARKIN, Iowa SLADE GORTON, Washington ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina HARRY REID, Nevada LARRY E. CRAIG, Idaho HERB KOHL, Wisconsin KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas PATTY MURRAY, Washington Majority Professional Staff CRAIG A. HIGGINS and BETTILOU TAYLOR Minority Professional Staff MARSHA SIMON (II) 2 CONTENTS Page Opening remarks of Senator Arlen Specter .......................................................... -

Torture and the Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of Detainees: the Effectiveness and Consequences of 'Enhanced

TORTURE AND THE CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DE- GRADING TREATMENT OF DETAINEES: THE EFFECTIVENESS AND CONSEQUENCES OF ‘EN- HANCED’ INTERROGATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 8, 2007 Serial No. 110–94 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–765 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:46 Jul 29, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\110807\38765.000 HJUD1 PsN: 38765 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. -

A Federal Commission for the Black Belt South

Professional Agricultural Workers Journal Volume 2 Number 1 Professional Agricultural Workers Article 6 Journal 9-4-2014 A Federal Commission for the Black Belt South Ronald C. Wimberley North Carolina State University, [email protected] Libby V. Morris The University of Georgia Rosalind Harris The University of Kentucky, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tuspubs.tuskegee.edu/pawj Part of the Agriculture Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Political Science Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Public Policy Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, and the Rural Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Wimberley, Ronald C.; Morris, Libby V.; and Harris, Rosalind (2014) "A Federal Commission for the Black Belt South," Professional Agricultural Workers Journal: Vol. 2: No. 1, 6. Available at: https://tuspubs.tuskegee.edu/pawj/vol2/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Tuskegee Scholarly Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Agricultural Workers Journal by an authorized editor of Tuskegee Scholarly Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FEDERAL COMMISSION FOR THE BLACK BELT SOUTH *Ronald C. Wimberley1, Libby V. Morris2, and Rosalind P. Harris3 1North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC; 2The University of Georgia, Athens, GA; 3The University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY *Email of lead author: [email protected] Abstract Recent legislation by the U.S. Congress authorized a federal regional commission for the Black Belt South. Three southern social scientists first proposed the commission at Tuskegee University’s Professional Agricultural Workers Conference in 1990. Following congressional seminars on the Black Belt by Ronald Wimberley and Libby Morris, the first legislation for the commission was introduced in the U.S. -

ALABAMA Senators Jeff Sessions (R) Methodist Richard C. Shelby

ALABAMA Senators Jeff Sessions (R) Methodist Richard C. Shelby (R) Presbyterian Representatives Robert B. Aderholt (R) Congregationalist Baptist Spencer Bachus (R) Baptist Jo Bonner (R) Episcopalian Bobby N. Bright (D) Baptist Artur Davis (D) Lutheran Parker Griffith (D) Episcopalian Mike D. Rogers (R) Baptist ALASKA Senators Mark Begich (D) Roman Catholic Lisa Murkowski (R) Roman Catholic Representatives Don Young (R) Episcopalian ARIZONA Senators Jon Kyl (R) Presbyterian John McCain (R) Baptist Representatives Jeff Flake (R) Mormon Trent Franks (R) Baptist Gabrielle Giffords (D) Jewish Raul M. Grijalva (D) Roman Catholic Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Roman Catholic Harry E. Mitchell (D) Roman Catholic Ed Pastor (D) Roman Catholic John Shadegg (R) Episcopalian ARKANSAS Senators Blanche Lincoln (D) Episcopalian Mark Pryor (D) Christian Representatives Marion Berry (D) Methodist John Boozman (R) Baptist Mike Ross (D) Methodist Vic Snyder (D) Methodist CALIFORNIA Senators Barbara Boxer (D) Jewish Dianne Feinstein (D) Jewish Representatives Joe Baca (D) Roman Catholic Xavier Becerra (D) Roman Catholic Howard L. Berman (D) Jewish Brian P. Bilbray (R) Roman Catholic Ken Calvert (R) Protestant John Campbell (R) Presbyterian Lois Capps (D) Lutheran Dennis Cardoza (D) Roman Catholic Jim Costa (D) Roman Catholic Susan A. Davis (D) Jewish David Dreier (R) Christian Scientist Anna G. Eshoo (D) Roman Catholic Sam Farr (D) Episcopalian Bob Filner (D) Jewish Elton Gallegly (R) Protestant Jane Harman (D) Jewish Wally Herger (R) Mormon Michael M. Honda (D) Protestant Duncan Hunter (R) Protestant Darrell Issa (R) Antioch Orthodox Christian Church Barbara Lee (D) Baptist Jerry Lewis (R) Presbyterian Zoe Lofgren (D) Lutheran Dan Lungren (R) Roman Catholic Mary Bono Mack (R) Protestant Doris Matsui (D) Methodist Kevin McCarthy (R) Baptist Tom McClintock (R) Baptist Howard P. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2008 No. 148 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. WELCOMING REV. DANNY DAVIS REPUBLICANS TO BLAME FOR Rev. Danny Davis, Mount Hermon ENERGY CRISIS The SPEAKER. Without objection, Baptist Church, Danville, Virginia, of- (Ms. RICHARDSON asked and was fered the following prayer: the gentlewoman from Virginia (Mrs. DRAKE) is recognized for 1 minute. given permission to address the House Loving God, You have shown us what for 1 minute and to revise and extend There was no objection. is good, and that is ‘‘to act justly, to her remarks.) love mercy, and to walk humbly with Mrs. DRAKE. Thank you, Madam Ms. RICHARDSON. Madam Speaker, our God.’’ Speaker. 3 years ago, Republicans passed an en- Help us, Your servants, to do exactly I am proud to recognize and welcome ergy plan that they said would lower that, to be instruments of both justice Dr. Danny Davis, the senior pastor at prices at the pump, drive economic and mercy, exercising those virtues in Mount Hermon Baptist Church in growth and job creation and promote humility. Your word requires it. Our Danville, Virginia. He is accompanied energy independence. I ask you, Amer- Nation needs it. today by his wife of 30 years, Sandy. ica, did it work? The answer is no. Forgive us when we have failed to do Dr. Davis was born in Tennessee and Now we look 3 years later and the that. -

Sunshine in the Courtroom Act of 2007

SUNSHINE IN THE COURTROOM ACT OF 2007 HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 2128 SEPTEMBER 27, 2007 Serial No. 110–160 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 37–979 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:09 Mar 11, 2009 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\FULL\092707\37979.000 HJUD1 PsN: 37979 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. WEINER, New York JIM JORDAN, Ohio ADAM B. -

H. Doc. 108-222

ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 2003, TO JANUARY 3, 2005 FIRST SESSION—January 7, 2003, 1 to December 8, 2003 SECOND SESSION—January 20, 2004, 2 to December 8, 2004 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—RICHARD B. CHENEY, of Wyoming PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—THEODORE F. STEVENS, 3 of Alaska SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—EMILY J. REYNOLDS, 3 of Tennessee SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—ALFONSO E. LENHARDT, 4 of New York; WILLIAM H. PICKLE, 5 of Colorado SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—J. DENNIS HASTERT, 3 of Illinois CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JEFF TRANDAHL, 3 of South Dakota SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—WILSON (BILL) LIVINGOOD, 3 of Pennsylvania CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER—JAMES M. EAGEN III, 3 of Pennsylvania ALABAMA Trent Franks, Phoenix Robert T. Matsui, 6 Sacramento SENATORS John B. Shadegg, Phoenix Lynn Woolsey, Petaluma Ed Pastor, Phoenix George Miller, Martinez Richard C. Shelby, Tuscaloosa J. D. Hayworth, Scottsdale Nancy Pelosi, San Francisco Jefferson B. Sessions III, Mobile Jeff Flake, Mesa Barbara Lee, Oakland REPRESENTATIVES Rau´ l M. Grijalva, Tucson Ellen O. Tauscher, Alamo Jo Bonner, Mobile Jim Kolbe, Tucson Richard W. Pombo, Tracy Terry Everett, Enterprise Tom Lantos, San Mateo Mike Rogers, Saks ARKANSAS Fortney Pete Stark, Fremont Robert B. Aderholt, Haleyville SENATORS Anna G. Eshoo, Atherton Robert E. (Bud) Cramer, Huntsville Blanche Lambert Lincoln, Helena Michael M. Honda, San Jose Spencer Bachus, Vestavia Hills Mark Pryor, Little Rock Zoe Lofgren, San Jose Artur Davis, Birmingham REPRESENTATIVES Sam Farr, Carmel Dennis A. Cardoza, Atwater Marion Berry, Gillett ALASKA George Radanovich, Mariposa Vic Snyder, Little Rock SENATORS Calvin M. -

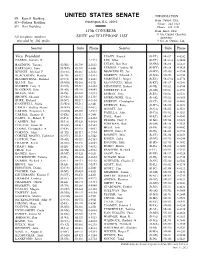

Senators Phone List.Pdf

UNITED STATES SENATE INFORMATION SR—Russell Building From Outside Dial: Washington, D.C. 20510 SD—Dirksen Building Senate—224–3121 SH—Hart Building House—225–3121 117th CONGRESS From Inside Dial: 0 for Capitol Operator All telephone numbers SUITE and TELEPHONE LIST Assistance preceded by 202 prefix 9 for an Outside Line Senator Suite Phone Senator Suite Phone Vice President LEAHY, Patrick (D-VT) SR-437 4-4242 HARRIS, Kamala D. 4-2424 LEE, Mike (R-UT) SR-361A 4-5444 BALDWIN, Tammy (D-WI) SH-709 4-5653 LUJAN, Ben Ray (D-NM) SR-498 4-6621 BARRASSO, John (R-WY) SD-307 4-6441 LUMMIS, Cynthia M. (R-WY) SR-124 4-3424 BENNET, Michael F. (D-CO) SR-261 4-5852 MANCHIN III, Joe (D-WV) SH-306 4-3954 BLACKBURN, Marsha (R-TN) SD-357 4-3344 MARKEY, Edward J. (D-MA) SD-255 4-2742 BLUMENTHAL, Richard (D-CT) SH-706 4-2823 MARSHALL, Roger (R-KS) SR-479A 4-4774 BLUNT, Roy (R-MO) SR-260 4-5721 McCONNELL, Mitch (R-KY) SR-317 4-2541 BOOKER, Cory A. (D-NJ) SH-717 4-3224 MENENDEZ, Robert (D-NJ) SH-528 4-4744 BOOZMAN, John (R-AR) SH-141 4-4843 MERKLEY, Jeff (D-OR) SH-531 4-3753 BRAUN, Mike (R-IN) SR-404 4-4814 MORAN, Jerry (R-KS) SD-521 4-6521 BROWN, Sherrod (D-OH) SH-503 4-2315 MURKOWSKI, Lisa (R-AK) SH-522 4-6665 BURR, Richard (R-NC) SR-217 4-3154 MURPHY, Christopher (D-CT) SH-136 4-4041 CANTWELL, Maria (D-WA) SH-511 4-3441 MURRAY, Patty (D-WA) SR-154 4-2621 CAPITO, Shelley Moore (R-WV) SR-172 4-6472 OSSOFF, Jon (D-GA) SR-455 4-3521 CARDIN, Benjamin L. -

Please Note: Seminar Participants Are * * * * * * * * * * * * Required to Read

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Woodrow Wilson School WWS 521 Fall 2014 Domestic Politics R. Douglas Arnold This seminar introduces students to the political analysis of policy making in the American setting. The focus is on developing tools for the analysis of politics in any setting – national, state, or local. The first week examines policy making with a minimum of theory. The next five weeks examine the environment within which policy makers operate, with special attention to public opinion and elections. The next six weeks focus on political institutions and the making of policy decisions. The entire course explores how citizens and politicians influence each other, and together how they shape public policy. The readings also explore several policy areas, including civil rights, health care, transportation, agriculture, taxes, economic policy, climate change, and the environment. In the final exercise, students apply the tools from the course to the policy area of their choice. * * * * * * Please Note: Seminar participants are * * * * * * * * * * * * required to read one short book and an article * * * * * * * * * * * * before the first seminar on September 16. * * * * * * A. Weekly Schedule 1. Politics and Policy Making September 16 2. Public Opinion I: Micro Foundations September 23 3. Public Opinion II: Macro Opinion September 30 4. Public Opinion III: Complications October 7 5. Inequality and American Politics October 14 6. Campaigns and Elections October 21 FALL BREAK 7. Agenda Setting November 4 8. Explaining the Shape of Public Policy November 11 9. Explaining the Durability of Public Policy November 18 10. Dynamics of Policy Change November 25 11. Activists, Groups and Money December 2 12. The Courts and Policy Change December 9 WWS 521 -2- Fall 2014 B. -

US Senate Vacancies

U.S. Senate Vacancies: Contemporary Developments and Perspectives Updated April 12, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44781 Filling U.S. Senate Vacancies: Perspectives and Contemporary Developments Summary United States Senators serve a term of six years. Vacancies occur when an incumbent Senator leaves office prematurely for any reason; they may be caused by death or resignation of the incumbent, by expulsion or declination (refusal to serve), or by refusal of the Senate to seat a Senator-elect or -designate. Aside from the death or resignation of individual Senators, Senate vacancies often occur in connection with a change in presidential administrations, if an incumbent Senator is elected to executive office, or if a newly elected or reelected President nominates an incumbent Senator or Senators to serve in some executive branch position. The election of 2008 was noteworthy in that it led to four Senate vacancies as two Senators, Barack H. Obama of Illinois and Joseph R. Biden of Delaware, were elected President and Vice President, and two additional Senators, Hillary R. Clinton of New York and Ken Salazar of Colorado, were nominated for the positions of Secretaries of State and the Interior, respectively. Following the election of 2016, one vacancy was created by the nomination of Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions as Attorney General. Since that time, one additional vacancy has occurred and one has been announced, for a total of three since February 8, 2017. As noted above, Senator Jeff Sessions resigned from the Senate on February 8, 2017, to take office as Attorney General of the United States.