Russian Gold and the Ruble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soviet Ruble, Gold Ruble, Tchernovetz and Ruble-Merchandise Mimeograph

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt258032tg No online items Overview of the Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Processed by Hoover Institution Archives Staff. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2009 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Overview of the Soviet ruble, YY497 1 gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Overview of the Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Hoover Institution Archives Staff Date Completed: 2009 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from MARC record by David Sun. © 2009 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Soviet ruble, gold ruble, tchernovetz and ruble-merchandise mimeograph Dates: 1923 Collection Number: YY497 Collection Size: 1 item (1 folder) (0.1 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Relates to the circulation of currency in the Soviet Union. Original article published in Agence économique et financière, 1923 July 18. Translated by S. Uget. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. -

Russian America and the USSR: Striking Parallels by Andrei V

Russian America and the USSR: Striking Parallels by Andrei V. Grinëv Translated by Richard L. Bland Abstract. The article is devoted to a comparative analysis of the socioeconomic systems that have formed in the Russian colonies in Alaska and in the USSR. The author shows how these systems evolved and names the main reason for their similarity: the nature of the predominant type of property. In both systems, supreme state property dominated and in this way they can be designated as politaristic. Politariasm (from the Greek πολιτεία—the power of the majority, that is, in a broad sense, the state, the political system) is formation founded on the state’s supreme ownership of the basic means of production and the work force. Economic relations of politarism generated the corresponding social structure, administrative management, ideological culture, and even similar psychological features in Russian America and the USSR. Key words: Russian America, USSR, Alaska, Russian-American Company, politarism, comparative historical research. The selected theme might seem at first glance paradoxical. And in fact, what is common between the few Russian colonies in Alaska, which existed from the end of the 18th century to 1867, and the huge USSR of the 20th century? Nevertheless, analysis of this topic demonstrates the indisputable similarity between the development of such, it would seem, different-scaled and diachronic socioeconomic systems. It might seem surprising that many phenomena of the economic and social sphere of Russian America subsequently had clear analogies in Soviet society. One can hardly speak of simple coincidences and accidents of history. Therefore, the selected topic is of undoubted scholarly interest. -

The Monetary Legacy of the Soviet Union / Patrick Conway

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE are published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics of Princeton University. The Section sponsors this series of publications, but the opinions expressed are those of the authors. The Section welcomes the submission of manuscripts for publication in this and its other series. Please see the Notice to Contributors at the back of this Essay. The author of this Essay, Patrick Conway, is Professor of Economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has written extensively on the subject of structural adjustment in developing and transitional economies, beginning with Economic Shocks and Structural Adjustment: Turkey after 1973 (1987) and continuing, most recently, with “An Atheoretic Evaluation of Success in Structural Adjustment” (1994a). Professor Conway has considerable experience with the economies of the former Soviet Union and has made research visits to each of the republics discussed in this Essay. PETER B. KENEN, Director International Finance Section INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION EDITORIAL STAFF Peter B. Kenen, Director Margaret B. Riccardi, Editor Lillian Spais, Editorial Aide Lalitha H. Chandra, Subscriptions and Orders Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conway, Patrick J. Currency proliferation: the monetary legacy of the Soviet Union / Patrick Conway. p. cm. — (Essays in international finance, ISSN 0071-142X ; no. 197) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88165-104-4 (pbk.) : $8.00 1. Currency question—Former Soviet republics. 2. Monetary policy—Former Soviet republics. 3. Finance—Former Soviet republics. I. Title. II. Series. HG136.P7 no. 197 [HG1075] 332′.042 s—dc20 [332.4′947] 95-18713 CIP Copyright © 1995 by International Finance Section, Department of Economics, Princeton University. -

Underpinning of Soviet Industrial Paradigms

Science and Social Policy: Underpinning of Soviet Industrial Paradigms by Chokan Laumulin Supervised by Professor Peter Nolan Centre of Development Studies Department of Politics and International Studies Darwin College This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Chokan Laumulin, Darwin College, Centre of Development Studies A PhD thesis Science and Social Policy: Underpinning of Soviet Industrial Development Paradigms Supervised by Professor Peter Nolan. Abstract. Soviet policy-makers, in order to aid and abet industrialisation, seem to have chosen science as an agent for development. Soviet science, mainly through the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, was driving the Soviet industrial development and a key element of the preparation of human capital through social programmes and politechnisation of the society. -

Russian Ruble, Rub

As of March 16th 2015 RUSSIA - RUSSIAN RUBLE, RUB Country: Russia Currency: Russian Ruble (RUB) Phonetic Spelling: {ru:bil} Country Overview Abbreviation: RUB FOREIGN EXCHANGE Controlled by the Central Bank of Russia (http://www.cbr.ru/eng/) The RUB continues Etymology to be affected by the oil price shock, escalating capital outflows, and damaging The origin of the word “rouble” is derived from the economic sanctions. The Russian ruble (RUB) continued to extend its losses and Russian verb руби́ть (rubit’), which means “to chop, cut, suffered its largest one-day decline on Dec 1st against the US dollar (USD) — less than to hack.” Historically, “ruble” was a piece of a certain a month after allowing the RUB to float freely. The RUB’s slide reflects the fact that weight chopped off a silver oblong block, hence the Russia is among the most exposed to falling oil prices and is particularly vulnerable to name. Another version of the word’s origin comes from the Russian noun рубец, rubets, which translates OPEC’s recent decision to maintain its supply target of 30-million-barrels per day. This to the seam that is left around the coin after casting, combined with the adverse impact of Western sanctions has contributed to the RUB’s therefore, the word ruble means “a cast with a seam” nearly 40% depreciation vis-à-vis the USD since the start of 2014. In this context, the Russian Central Bank will likely hike interest rates at its next meeting on December In English, both the spellings “ruble” and “rouble” are 11th. -

A Case Study of a Currency Crisis: the Russian Default of 1998

agents attempting to alter their portfolio by buying A Case Study of a another currency with the currency of country A.2 This might occur because investors fear that the Currency Crisis: The government will finance its high prospective deficit through seigniorage (printing money) or attempt to Russian Default of 1998 reduce its nonindexed debt (debt indexed to neither another currency nor inflation) through devaluation. Abbigail J. Chiodo and Michael T. Owyang A devaluation occurs when there is market pres- sure to increase the exchange rate (as measured by currency crisis can be defined as a specula- domestic currency over foreign currency) because tive attack on a country’s currency that can the country either cannot or will not bear the cost A result in a forced devaluation and possible of supporting its currency. In order to maintain a debt default. One example of a currency crisis lower exchange rate peg, the central bank must buy occurred in Russia in 1998 and led to the devaluation up its currency with foreign reserves. If the central of the ruble and the default on public and private bank’s foreign reserves are depleted, the government debt.1 Currency crises such as Russia’s are often must allow the exchange rate to float up—a devalu- thought to emerge from a variety of economic condi- ation of the currency. This causes domestic goods tions, such as large deficits and low foreign reserves. and services to become cheaper relative to foreign They sometimes appear to be triggered by similar goods and services. The devaluation associated with crises nearby, although the spillover from these con- a successful speculative attack can cause a decrease tagious crises does not infect all neighboring econ- in output, possible inflation, and a disruption in omies—only those vulnerable to a crisis themselves. -

The Ascend and Descend of Communism in East-Central Europe: an Historical- Opinionated Analysis

European Scientific Journal July 2015 edition vol.11, No.20 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 THE ASCEND AND DESCEND OF COMMUNISM IN EAST-CENTRAL EUROPE: AN HISTORICAL- OPINIONATED ANALYSIS Dr. Abdul Zahoor Khan, PhD In-Charge, Department of History & Pakistan Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Faculty Block#I, First Floor, New Campus, Sector#H-10, International Islamic University, Islamabad-Pakistan Abstract The year of 1989 marked a turning point in world history. During the last six months of that year, the world witnessed the collapse of communism in East-Central Europe. Two years later, communism was abolished in the Soviet Union, and that country began to fall apart. These changes were stunning and unprecedented in terms of their breadth, depth, and speed. In 1989, Hungary and Poland led the way, though cautiously. In February of that year, the Hungarian communist party leadership officially sanctioned the emergence of opposition parties the beginning of the end of the party's monopoly of power. In Poland a few months later, after a long series of roundtable negotiations between the communist party leadership and the opposition, the regime agreed to partially contested elections to the country's national legislature. Within the countries of East-Central Europe, the social, economic, and political changes were as fundamental as were those in France and Russia after their revolutions. In every country in the region the transition to Western style parliamentary democracy meant a fundamental restructuring of the political system, a proliferation of new interest groups and parties, and upheaval within the bureaucracy and administration. -

Glasnost in Jeopardy Glasnost in Jeopardy

GLASNOST IN JEOPARDY Human Rights in the USSR April 1991 A Helsinki Watch Report 485 Fifth Avenue 1522 K Street, NW, #910 New York, NY 10017 Washington, DC 20005 Tel (212) 972-8400 Tel (202) 371-6592 Fax (212) 972-0905 Fax (202) 371-0124 Copyright 8 March 1991 by Human Rights Watch All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 0-929692-89-6 Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 91-71495 Cover Design by Deborah Thomas The Helsinki Watch Committee Helsinki Watch was formed in 1978 to monitor and promote observance of domestic and international compliance with the human rights provisions of the 1975 Helsinki Accords. The Chairman is Robert L. Bernstein; Vice Chairs, Jonathan Fanton and Alice Henkin; Executive Director, Jeri Laber; Deputy Director, Lois Whitman; Washington Representative, Catherine Cosman; Staff Counsel, Holly Cartner and Theodore Zang, Jr.; Staff Consultant, Ivana Nizich; Orville Schell Intern, Robert Kushen; Intern, Jemima Stratford; Associates, Sarai Brachman, Mia Nitchun, and Elisabeth Socolow. Helsinki Watch is affiliated with the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, which is based in Vienna. Human Rights Watch Helsinki Watch is a component of Human Rights Watch, which includes Americas Watch, Asia Watch, Africa Watch, and Middle East Watch. The Chairman is Robert L. Bernstein and the Vice Chairman is Adrian W. DeWind. Aryeh Neier is Executive Director; Kenneth Roth, Deputy Director; Holly J. Burkhalter, Washington Director; Susan Osnos, Press Director. Executive Directors Africa Watch, Rakiya Omaar; Americas Watch, Juan Mendez; Asia Watch, Sidney R. Jones; Helsinki Watch, Jeri Laber; Middle East Watch, Andrew Whitley. -

Belarus Country Report BTI 2016

BTI 2016 | Belarus Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.27 # 99 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.93 # 91 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.61 # 90 of 129 Management Index 1-10 3.02 # 115 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2016. It covers the period from 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2015. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2016 — Belarus Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2016 | Belarus 2 Key Indicators Population M 9.5 HDI 0.786 GDP p.c., PPP $ 18184.9 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.0 HDI rank of 187 53 Gini Index 26.0 Life expectancy years 72.5 UN Education Index 0.820 Poverty3 % 0.0 Urban population % 76.3 Gender inequality2 0.152 Aid per capita $ 11.1 Sources (as of October 2015): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2015 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2014. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.10 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Summer 2014 marked the 20th anniversary of Aliaksandr Lukashenka’s election as the first, and so far only, president of the Republic of Belarus. -

Currencies of the World

The World Trade Press Guide to Currencies of the World Currency, Sub-Currency & Symbol Tables by Country, Currency, ISO Alpha Code, and ISO Numeric Code € € € € ¥ ¥ ¥ ¥ $ $ $ $ £ £ £ £ Professional Industry Report 2 World Trade Press Currencies and Sub-Currencies Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies of the World of the World World Trade Press Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s 800 Lindberg Lane, Suite 190 Petaluma, California 94952 USA Tel: +1 (707) 778-1124 x 3 Introduction . 3 Fax: +1 (707) 778-1329 Currencies of the World www.WorldTradePress.com BY COUNTRY . 4 [email protected] Currencies of the World Copyright Notice BY CURRENCY . 12 World Trade Press Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies Currencies of the World of the World © Copyright 2000-2008 by World Trade Press. BY ISO ALPHA CODE . 20 All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the express written permission of the Currencies of the World copyright holder is unlawful. Requests for permissions and/or BY ISO NUMERIC CODE . 28 translation or electronic rights should be addressed to “Pub- lisher” at the above address. Additional Copyright Notice(s) All illustrations in this guide were custom developed by, and are proprietary to, World Trade Press. World Trade Press Web URLs www.WorldTradePress.com (main Website: world-class books, maps, reports, and e-con- tent for international trade and logistics) www.BestCountryReports.com (world’s most comprehensive downloadable reports on cul- ture, communications, travel, business, trade, marketing, -

Bretton-Woods Conference: the Soviets Perspective

Erasmus University Rotterdam Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication M.A. History of Society Global History and International Relations Bretton-Woods Conference: the Soviets Perspective Student: Natalia Klyausova Student number: 429910 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ben Wubs 2015/2016 Abstract This paper examines the reasons of the Soviet Union’s decision not to ratify the Bretton-Woods agreement. The Bretton-Woods Conference was a symbol of the Twentieth Century, which left a mark in the international financial history. The Conference gathered more than 730 delegates from 44 countries that wanted to avoid the financial catastrophe in the postwar period. The Soviet Union participated in the pre-conference meetings and was actively engaged in defending its national interests at the Bretton-Woods Conference. However, the Soviet Union refused to enter the newly founded IMF and IBRD, and reasons behind the refusal are merely mentioned in various sources. The most common information that could be found is that the Soviet Union never officially explained its decision. The result of the work shows that the Soviet officials studied and favored the Bretton-Woods agreements, explaining that the Soviet Union could derive a profit from it. Moreover, the Soviet economic technicians prepared a set of the recommendations which the Soviet government needed to apply before entering the Bretton- Woods institutions. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union never ratified the Bretton-Woods outcome. Although, there are no official reports or papers which might shed the light on the final decision of Stalin, who refused to become a part of the new financial order, this work still contributes to the common knowledge of Bretton-Woods and the role of the Soviet Union in the Bretton- Woods system and the postwar world. -

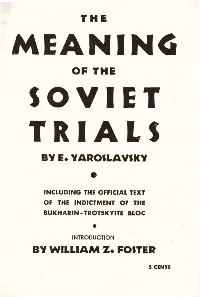

The Meaning of the Soviet Trials

OF THE INCLUDING f HE OFFICIAL TEXT OF THE INDICTMENT OF THE BUKHARIN - TROTSKY ITE BLOC INTRODUCTION ' BY WILLIAM Z* FOSTER INTRODUCTION HE sound and the fury set up by the enemies of the Soviet Union around the Trotskyite- TBidcharin trials should confuse no one. The first workers' and farmcrs' government is today bring- ing to justice the last of the leading groups of pro-fascist plotters, promoters of war, and sabotages of socialist progress. The Soviet people are building a gteat, new, free society, instead of the old society where the rich exploit the poor; they are uniting the nations of one-sixth of the earth's surface into a sin- gle classless commonwealth. Those who are trying to stop this progress by treason and assassination, to betray the Soviet people into the hands of the fascist barbarians, must expect to pay the price of their treachery when caught. When Aaron Burr, one-time Vice-President of the tTnited States, together with some army officers and abut 2,000 co-conspirators, attempted to betray the young United States republic and was properly crushed, Thomas Jefferson declared concerning the ensuing furore: "On the whole, this squall, by showing with what eax our government suppresses movemenxs which in other countries requires armies, has greatly increased its strength hy increasing the puhlic ctmfidcrlce in it." This well applies to the Soviet government today. The crushitlg of the 'Trotskyist-Bukharinist unprin- cipled and areerist plotters is a gain for humanity. To yield to the misguided liberal-who, under the 2 illusion that they are demanding democracy, want to give a free hand to these wretched conspiracies-- would be to endanger the safety of 1 73,000,000 So- viet ~eople,not to speak of the peace of the world.