Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uaker Eligious Hought

QUAKER ELIGIOUS R HOUGHT T A Friendly Apology for the 21st Century No Apology Required: Quaker Fragmentation and the Impossibility of a Unified Confessional Apologia . 5 David L. Johns An Apology for Authentic Spirituality . 20 Paul Anderson Responses to Johns and Anderson . 38 Arthur O. Roberts; Stephen W. Angell Responses to “Quakers and Levinas,” QRT #113 Levinas, Quakers and the (In)Visibility of God: Responses to Jeffrey Dudiak and Corey Beals . 53 Rachel Muers An Appreciative Response to Corey Beals and Jeff Dudiak . 57 Richard J. Wood Cumulative No . 114 April 2010 QUAKER RELIGIOUS THOUGHT Cumulative Number 114 April 2010 Sponsored by the Quaker Theological Discussion Group (http://theo-discuss.quaker.org/) The purpose of the Quaker Theological Discussion Group is to explore the meaning and implications of our Quaker faith and religious experience through discussion and publication. This search for unity in the claim of truth upon us concerns both the content and application of our faith. Paul Anderson, Editor ([email protected]) Howard R. Macy, Associate Editor ([email protected]) David Johns, Associate Editor ([email protected]) Arthur O. Roberts, Associate Editor ([email protected]) Gayle Beebe, Associate Editor ([email protected]) Phil Smith, Business Manager ([email protected]) Wess Daniels, Website Manager ([email protected]) Advisory Council: Carole Spencer, Ben Pink Dandelion, Ruth Pitman, John Punshon, Max Carter, Stephen Angell, Jeffrey Dudiak, Corey Beals, and Susan Jeffers Address editorial correspondence only to: Paul Anderson, Box 6032, George Fox University, Newberg, OR 97132 Quaker Religious Thought is published two times each year; the Volume numbers were discontinued after Vol. -

The Experience of Early Friends

The Experience of Early Friends By Andrew Wright 2005 Historical Context The world of the early Friends was in the midst of radical change. The Renaissance in Europe had strengthened the role of science and reason in the Western world. The individual’s power to understand and make sense of reality on their own was challenging the authority of the Catholic Church. Until recently there had been only one church in Western Europe. Martin Luther’s “95 Theses” that critiqued the Catholic Church is generally seen as the beginning of the Reformation when western Christianity splintered into a plethora of various “protestant” churches. In order to fully understand the significance of the Reformation we must realize that political authority and religious authority were very closely aligned at this time in history. Political authority was used to enforce religious orthodoxy as well as to punish those who expressed unconventional views. Meditating on the intensity of feeling that many have today about issues like abortion or gay/ lesbian rights or end of life issues might begin to help us to understand the intensity of feeling that people experienced around religious issues during the Reformation. Many people felt like only the triumph of their religious group could secure their right to religious expression or save them from persecution. The notion of separation of church and state only began to become a possibility much later. The English Reformation and Civil War In England, the reformation developed a little later than in Germany and in a slightly different way. In 1534, King Henry VIII declared the Church of England independent of the Roman Catholic papacy and hierarchy. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Thomas Rudyard Early Friends' "Oracle of Law"

Thomas Rudyard Early Friends' "Oracle of Law" By ALFRED W. BRAITHWAITE FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY FRIENDS HOUSE, EUSTON ROAD, LONDON, N.W.i also obtainable at the Friends' Book Store, 302 Arch Street, Philadelphia 6, Pa., U.S.A. PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY HEADLEY BROTHERS LTD 109 KINGSWAY LONDON WC2 AND ASHFORD KENT Thomas Rudyard EARLY FRIENDS' "ORACLE OF LAW" HE earliest Friends had not much use for lawyers. This is true, I think, both colloquially and literally. TFor the colloquial sense we need not look further than the first few pages of George Fox's Journal, where Fox describes how, in one of the apocalyptic visions he had at the beginning of his ministry, the Lord opened to him "three things relating to those three great professions in the world, physic, divinity (so called), and law"; how the physicians were "out of the wisdom of God by which the creatures were made," the priests were "out of the true faith," and the lawyers were "out of the equity and out of the true justice, and out of the law of God." 1 This passage, though written at a much later date, and containing certain expressions used by Fox later,2 seems to reflect fairly the attitude of the earliest Friends. They were not anarchists; they believed in the rule of law;3 but they did not believe in law as administered by lawyers. In a pamphlet published in 1658 Fox wrote: "I see a darkness among the Lawyers, selfishness, wilfulness, and earthliness and unreasonableness," and in another place: "I beheld the Lawyers black, their black robe as a puddle, and like unto a black pit, almost covered over with black ness, yet there was a righteousness in the middle, which their unreasonableness run from."4 1 Journal, p. -

Barclays of Urie

A GENEALOGICAL ACCOUNT OF THE BARCLAYS OF URIE, FOR UPWARDS Or SEVEN HUNDRED YEARS: WITH MEMOIRS OF COLONEL DAVID BARCLAY, AND HIS SON ROBERT BARCLAY, Author of the Apology for the People called Quakers. ALSO LETTERS That passed between him, THE DUKE OF YORK, ELIZABETH PRINCESS PALATINE OF THE IMINE, ARCHBISHOP SHARP, THE EARL OF PERTH, And other Distinguished Characters; CONTAINING CURIOUS AND INTERESTING INFORMATION, NEVER BEFORE PUBLISHED. LONDON: PRINTED FOR THE EDITOR, BY JOHN HERBERT, NO. 10, BOROUGH ROAD ; AND SOLD BY WILLIAM PHILLIPS, GEORGE-YARD, LOMBARD-STREET; AND MESSRS. JOHN AND ARTHUR ARCH, CORNHILL. 1812. PREFACE. i r | ^HE following little work contains so many curious anecdotes relative to the celebrated Apologist of the Quakers, that, by giving it a greater degree of pub- licity, I trust I shall render an acceptable service to the literary world, and particu- larly to that respectable class of Christians whose cause he defended with such zeal, and whose tenets he explained with such ability, as to convert into an appellation of honourable distinction what was in- tended by their calumniators as a stigma of reproach. VI The Memoirs were written about the year 1 740, by Robert Barclay, the son of the Apologist, and printed chiefly for dis- tribution among his relatives and friends. Having been born in the neighbourhood of Urie, and during my early youth much connected with the Quakers in my native county, a copy was presented to me by a friend in 17/4, and has since that time been preserved with great care ; having many years ago considered it, on account of its rarity and intrinsic value, worthy of being re-printed and published. -

TURNING HEARTS to BREAK OFF the YOKE of OPPRESSION': the TRAVELS and SUFFERINGS of CHRISTOPHER MEIDEL C

Quaker Studies Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 5 2008 'Turning Hearts to Break Off the okY e of Oppression': The rT avels and Sufferings of Christopher Meidel, c. 1659-c. 1715 Richard Allen University of Wales Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Allen, Richard (2008) "'Turning Hearts to Break Off the oY ke of Oppression': The rT avels and Sufferings of Christopher Meidel, c. 1659-c. 1715," Quaker Studies: Vol. 12: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol12/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUAKER STUDIES 1211 (2007) (54-72] ISSN 1363-013X 'TURNING HEARTS TO BREAK OFF THE YOKE OF OPPRESSION': THE TRAVELS AND SUFFERINGS OF CHRISTOPHER MEIDEL c. 1659-c. 1715* Richard Allen University of Wales ABSTRACT This study of Christopher Meidel, a Norwegian Quaker writer imprisoned both in England and on the Continent for his beliefs and actions, explores the life of a convert to Quakerism and his missionary zeal in the early eighteenth century. From Meidel's quite tempestuous career we receive insights into the issues Friends faced in Augustan England in adapting to life in a country whose inter-church relations were largely governed by the 1689 Toleration Act, and its insistence that recipients of toleration were to respect the rights of other religionists. -

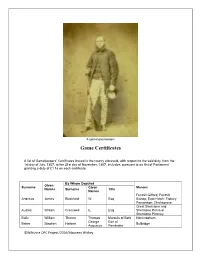

Game Certificates

A typical gamekeeper Game Certificates A list of Gamekeepers’ Certificates issued in the county aforesaid, with respect to the said duty, from the 1st day of July, 1807, to the 21st day of November, 1807, inclusive, pursuant to an Act of Parliament granting a duty of £1 1s on each certificate. By Whom Deputed Given Surname Given Manors Names Surname Title Names Fonthill Gifford; Fonthill Andrews James Blackford W. Esq. Bishop; East Hatch; Tisbury Parsonage; Chicksgrove Great Sherstone and Austen William Cresswell E. Esq. Sherstone Parva or Sherstone Pinkney Baily William Thynne Thomas Marquis of Bath Horningsham George Earl of Baker Stephen Herbert Bulbridge Augustus Pembroke ©Wiltshire OPC Project/2016/Maureen Withey Barnes William Wyndham W. Esq. Teffont Evias Littlecot with Rudge; Chilton Foliat with Soley; North Standen with Oakhill; & Charnham Street; with liberty Popham E. W. L. Esq. to kill game within the said manors of Littlecot with Rudge and Chilton Foliat with Soley Goddard A. Esq. Wither L. B. Esq. Northey W. Esq. Barrett Joseph Brudenell- Thomas Earl of Ailesbury Bruce Rev., D.D., Popham E. Clerk Froxfield Vilet T. G. Rev., Ll.d., Clerk Rt. Hon., Bruce C. B. commonly called Lord Bruce Goddard E. Rev., Clerk Michell T. Esq. Warneford F. Esq. North Tidworth; otherwise Batchelor Henry Poore E. Dyke Esq. Tidworth Zouch; and Figheldean Scrope W. Esq. Castle Coomb Beak William Sevington Vince H. C. Esq. Leigh-de-la-Mare Beck Thomas Astley F .D. Esq Boreham Pewsey; within the tithings of Beck William Astley F. D. Esq. Southcott and Kepnell Bennett John Williams S. -

Observations Made During a Tour Through Parts of England, Scotland

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com OBSERVATIO NS MADE DURING A T O U R THROUGH PARTS OP ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, and WALES. CONTENTS. Letter I. — Page i. TOPISTOLART introduction — The cause of travelling traced to its source — Of man in an uncultivated Jlate — In the first stages of society — In a more civilized condition — 'The advantages arising from travelling — "The different closes of travellers described — Observations on the extent of the metropolis of England — Pleasures attainable in London — Reflections on the wretched sttuation of women of the town, and on their seducers — A story of uncommon resolution — Of the Opera, Pantheon, Play-houses, &c. Letter II. — Page i3. Observations on sundry places in a journey from London to Bath, Richmond, Windsor — Meditations on human nature, excited by a walk on the terrace of Windsor castle. Letter III. — Page i9. The journey continued — Eaton college — The advantages and disad vantages of a public and of a private education pointed out, and the . preference given to the former — Account of an abrupt secession upon some disgust of the scholars belonging to Eaton school — Maidenhead bridge — Cliefden house — The city of Bath — Its antiquity — Baths — Quality of the waters — Buildings — Amusements — Prior park, with a poetical description of it by Mrs. Chandler. Letter IV. — Page 30. A tour from Bath through some of the southern parts of England . — Mendip-hills — The city of Wells — Its cathedral, and public build ings — Instance of filial ajfeclion — Ancient tombs — The library — A literary imposition detebled — Description of Okey-Hole, a famous cavern a near CONTENTS. -

The History of Middlesex County Ended As the County’S Original Settlers Were Permanently Displaced by the European Newcomers

HISTORY BUFF’S THETHE HITCHHIKER’SHITCHHIKER’S GUIDEGUIDE TOTO MIDDLESEXMIDDLESEX COUNTYCOUNTY “N.E. View of New Brunswick, N.J.” by John W. Barber and Henry Howe, showing the Delaware and Raritan Canal, Raritan River, and railroads in the county seat in 1844. Thomas A. Edison invented the Phonograph at Menlo Park (part of Edison) in 1877. Thomas Edison invented the incandescent Drawing of the Kilmer oak tree by Joan Labun, New Brunswick, 1984. Tree, which light bulb at Menlo Park (part of Edison) in inspired the Joyce Kilmer poem “Trees” was located near the Rutgers Labor Education 1879. Center, just south of Douglass College. Carbon Filament Lamp, November 1879, drawn by Samuel D. Mott MIDDLESEX COUNTY BOARD OF CHOSEN FREEHOLDERS Christopher D. Rafano, Freeholder Director Ronald G. Rios, Deputy Director Carol Barrett Bellante Stephen J. Dalina H. James Polos Charles E. Tomaro Blanquita B. Valenti Compiled and written by: Walter A. De Angelo, Esq. County Administrator (1994-2008) The following individuals contributed to the preparation of this booklet: Clerk of the Board of Chosen Freeholders Margaret E. Pemberton Middlesex County Cultural & Heritage Commission Anna M. Aschkenes, Executive Director Middlesex County Department of Business Development & Education Kathaleen R. Shaw, Department Head Carl W. Spataro, Director Stacey Bersani, Division Head Janet Creighton, Administrative Assistant Middlesex County Office of Information Technology Khalid Anjum, Chief Information Officer Middlesex County Administrator’s Office John A. Pulomena, County Administrator Barbara D. Grover, Business Manager Middlesex County Reprographics Division Mark F. Brennan, Director Janine Sudowsky, Graphic Artist ii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... Page 1 THE NAME ................................................................................... Page 3 THE LAND .................................................................................. -

Mr. Nisbet's Legacy, Or the Passing of King William's Act in 1699

Document généré le 25 sept. 2021 11:29 Newfoundland Studies Mr. Nisbet’s Legacy, or the Passing of King William’s Act in 1699 Alan Cass Volume 22, numéro 2, autumn 2007 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds22_2art05 Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 0823-1737 (imprimé) 1715-1430 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Cass, A. (2007). Mr. Nisbet’s Legacy, or the Passing of King William’s Act in 1699. Newfoundland Studies, 22(2), 505–543. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2007 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Mr. Nisbet’s Legacy, or the Passing of King William’s Act in 1699 ALAN CASS INTRODUCTION AN ACT TO ENCOURAGE THE TRADE TO NEWFOUNDLAND,10&11Wm.III, cap. 25, popularly known as King William’s Act, was given royal assent on 4 May 1699.1 This was the only act of Parliament that regulated the English fishery in Newfound- land until the supplementary act 15 Geo. III cap. 31 of 1775, An Act for the Encour- agement of the Fisheries .. -

188041986.23.Pdf

A LIST of the Principal Officers, Civil and Military, in England, in the Year 1704. Dutchy of Lancatter. Surrey, George Duke of Northumberland. Tho. Jay ffj; Major. On the Northfide 7%-- Tt hltnr.'surahle the Lords, and others^ e/Trent. Chancellor, John Lcvefon Lord Gower. Tower and Hamlets, Montaguc-Venables Richard Mordley, Guidon.- ef Her MayJij S Mo(i Honourable ?nvy William Duke of Deyonfhire. Attorney-General, Sir Edw* Northey Kt. Earl of Abingdon. Royal Regiment ofHorfs, 9 Troops Pusngerefs of Wind for Forefi, Council. Receiver General, John Chetwind Efq; Warwick, G'orge Earl of Northampton, 4® in a Troop. Sarah Dutchedof Marlborough. Auditor of the North, Hen. Aylojfe, Efq; Northwales, Hugh Lord Cholmondley. George Duke of Northumberland* PRince George of Denmark, Ld High War dm */New Eorreft. Auditor of the South, Tho. Gower Efq; North-Riding of York, John Duke of Sir Francis Compton, Lieut. CoS. Admiral of England. Charles Duke of Bolton. CJerk of the Council, Cheek Gcrrard Efq; Buckingham. - George Kirk, Major. Dr.Temifon, Ld Archbifhop o£Canterbury. Ranger e/Hide Park. Lord Conway. Vice-Chan.of Wm.Brennane Efq; Weft Riding of York, Charles Earl of Queen’s Regiment in Holland, 63 Sit Nathan IVrighte, Lord Keeper. Ranger of St. James’s Park. Attor. -Gen of Lane af Nich. Starkey Efq; Burlington. Troops, 36 in each, 390. Dr. Sharp Lord Archbifliop^f ttrf. fohn Lord Grandvill. Deputy, tffic. Mr. John Baker. Henry Lumley, Lieut. General, Coll. Confiables and Governors of Cafiles arA Sidney Lord Godolfhin, Ld High Treaf. v/arden of the Forrefi o/ShetWOod. Attornies, Mr. -

![Sir Thomas Phillipps Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5923/sir-thomas-phillipps-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2885923.webp)

Sir Thomas Phillipps Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Sir Thomas Phillipps Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2009 Revised 2018 February Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms014065 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm78076737 Prepared by Carolyn Sung, Allison Davis, and Audrey A. Walker Collection Summary Title: Sir Thomas Phillipps Collection Span Dates: 1400-1857 ID No.: MSS76737 Creator: Phillipps, Thomas, Sir, 1792-1872 Extent: 1,100 items ; 63 containers plus 1 oversize ; 13.3 linear feet ; 10 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Manuscript materials relating chiefly to various aspects of the colonial history of British North America and the West Indies. Formerly a part of Bibliotheca Phillippica, a library of manuscripts and printed books compiled by Sir Thomas Phillipps. Of particular note are papers relating to the Board of Trade and Sir William Blathwayt; letterbooks of George Macartney while governor of the Caribbean Islands; English and Italian genealogical material; papers of Jean Louis Berlandier relating to his surveys of the United States-Mexican border and to his various explorations in Mexico, Lower California, and Texas; English court records and reports; and miscellaneous papers of various colonies in British North America. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein.