Champlain and the Odawa in 1615

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Robes at the Edge of Empire: Jesuits, Natives, and Colonial Crisis in Early Detroit, 1728-1781 Eric J

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-10-2019 Black Robes at the Edge of Empire: Jesuits, Natives, and Colonial Crisis in Early Detroit, 1728-1781 Eric J. Toups University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Toups, Eric J., "Black Robes at the Edge of Empire: Jesuits, Natives, and Colonial Crisis in Early Detroit, 1728-1781" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2958. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2958 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLACK ROBES AT THE EDGE OF EMPIRE: JESUITS, NATIVES, AND COLONIAL CRISIS IN EARLY DETROIT, 1728-1781 By Eric James Toups B.A. Louisiana State University, 2016 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2019 Advisory Committee: Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Advisor Stephen Miller, Adelaide & Alan Bird Professor and History Department Chair Liam Riordan, Professor of History BLACK ROBES AT THE EDGE OF EMPIRE: JESUITS, NATIVES, AND COLONIAL CRISIS IN EARLY DETROIT, 1728-1781 By Eric James Toups Thesis Advisor: Dr. Jacques Ferland An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in History) May 2019 This thesis examines the Jesuit missionaries active in the region of Detroit and how their role in that region changed over the course of the eighteenth century and under different colonial regimes. -

The Route and Purpose of Champlain's Journey to the Petun in 1616

Document généré le 24 sept. 2021 08:18 Ontario History The Route and Purpose of Champlain’s Journey to the Petun in 1616 Charles Garrad Volume 107, numéro 2, fall 2015 Résumé de l'article Dans cet essai, nous revisitons l’expédition entreprise par Samuel de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1050633ar Champlain, lors de laquelle il rencontra les Odawas, les Petuns, ainsi que des DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1050633ar délégations de Neutres qui se trouvaient dans la région. Tout en confirmant les conclusions déjà établies, nous émettons de nouvelles hypothèses sur les Aller au sommaire du numéro raisons pourquoi la poursuite de la route qui conduirait vers les Neutres et ensuite vers l’Orient n’a pas eu lieu.. Éditeur(s) The Ontario Historical Society ISSN 0030-2953 (imprimé) 2371-4654 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Garrad, C. (2015). The Route and Purpose of Champlain’s Journey to the Petun in 1616. Ontario History, 107(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050633ar Copyright © The Ontario Historical Society, 2015 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. -

The Mckee Treaty of 1790: British-Aboriginal Diplomacy in the Great Lakes

The McKee Treaty of 1790: British-Aboriginal Diplomacy in the Great Lakes A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN Saskatoon by Daniel Palmer Copyright © Daniel Palmer, September 2017 All Rights Reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History HUMFA Administrative Support Services Room 522, Arts Building University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i Abstract On the 19th of May, 1790, the representatives of four First Nations of Detroit and the British Crown signed, each in their own custom, a document ceding 5,440 square kilometers of Aboriginal land to the Crown that spring for £1200 Quebec Currency in goods. -

The Mapping of Samuel De Champlain, 1603–1635 Conrad E

51 • The Mapping of Samuel de Champlain, 1603–1635 Conrad E. Heidenreich The cartography of Samuel de Champlain marks the be- roster of 1595 he was listed as a fourier (sergeant) and aide ginning of the detailed mapping of the Atlantic coast north to the maréchal de logis (quartermaster), apparently of Nantucket Sound, into the St. Lawrence River valley, reaching the rank of maréchal himself.4 The same pay ros- and, in a more cursory fashion, to the eastern Great Lakes. ter states that in 1595 he went on a secret mission for the Previous maps were based on rapid ship-board reconnais- king that was regarded to be of some importance. He also sance surveys made in the early to middle sixteenth cen- made a “special report” to Henri IV after his West Indian tury, particularly on the expeditions of Jacques Cartier and voyage (1601) and after the first two voyages to Canada Jean-François de La Rocque, sieur de Roberval (1534 – (1603 and 1607). These reports seem to indicate that 43). These maps conveyed little more than the presence of Champlain had a personal relationship with Henri IV, a stylized coastline. The immediate result of the Cartier- probably accounting for the pension the king awarded him Roberval expeditions was that France lost interest in sometime before 1603.5 After the war, Champlain joined North America, except for fishing off the northeast coast. his uncle’s ship, the 500-tun Saint-Julien, in Spanish The indigenous population was considered impoverished Caribbean service.6 In June 1601, Champlain was in and hostile, there were no quick riches, and the winters Cádiz where he was a witness to his dying uncle’s testa- were so brutal that the French wondered whether Euro- ment leaving him a large estate near La Rochelle as well as peans could live there. -

The Four Main Groups of the Ojibwe Published on Lessons of Our Land (

The Four Main Groups of the Ojibwe Published on Lessons of Our Land (http://www.lessonsofourland.org) Grades: 6th - 8th Grade Lesson: 1 Unit: 2: American Indian land tenure history Subject: History/Social Studies Additional Subject(s): Geography Achievement Goal: Students will identify the four main groups of the Ojibwe and the large land mass they covered. They will understand that each group lived in a different geographical location and their cultures varied with their environments. Time: One class period Lesson Description: Students learn about the four nations of the Ojibwe tribe and analyze maps of the Great Ojibwe Migration. Teacher Background: Refer to The Four Divisions of the Ojibwe Nation Map found in the Lesson Resources section. This map shows the Ojibwe homeland. It is important to remember that much of it was shared with other tribes. The lines only serve to show where fairly large numbers of Ojibwe lived at one time or another. Within this wide expanse there are great differences in country and climate, and the Ojibwe people adapted their ways of living to their surroundings. In modern times four main groups have been distinguished by location and adaptation to varying conditions. They are the Plains Ojibwe, the Northern Ojibwe, the Southeastern Ojibwe, and the Southwestern Ojibwe or Chippewa. The Plains Ojibwe The Plains Ojibwe live in Saskatchewan, western Manitoba, North Dakota, and Montana. Although they were originally a forest people, they changed their way of life when they moved into the open lands and borrowed many customs of other plains people. Today most of them work at farming and ranching. -

History of Toronto from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia the History of Toronto, Ontario, Canada Begins Several Millennia Ago

History of Toronto From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The history of Toronto, Ontario, Canada begins several millennia ago. Archaeological finds in the area have found artifacts of First Nations settlements dating back several thousand years. The Wyandot people were likely the first group to live in the area, followed by the Iroquois. When Europeans first came to Toronto, they found a small village known as Teiaiagon on the banks of the Humber River. Between visits by European explorers, the village was abandoned by the Iroquois, who moved south of Lake Ontario and the Mississaugas, a branch of the Ojibwa settled along the north shore of the lake. The French first set up trading posts in the area, including Fort Rouillé in 1750, which they abandoned as the British conquered French North America. In 1788, the British negotiated the first treaty to take possession of the Toronto area from the Mississaugas. After the United States War of Independence, the area north of Lake Ontario was held by the British who set up the province of Upper Canada in 1791. See also: Name of Toronto https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:DavenportBathurstSoutheast.jpg Davenport Road, as shown here in 1914, does not follow Toronto's standard street grid pattern, as it originated as a First Nations travel route between the Humber River and the Don Valley named Gete-Onigaming, Ojibwe for "at the old portage."[1] Toronto is located on the northern shore of Lake Ontario, and was originally a term of indeterminate geographical location, designating the approximate area of the future city of Toronto on maps dating to the late 17th and early 18th century. -

Feasibility Study on a Potential Susquehanna Connector Trail for the John Smith Historic Trail

Feasibility Study on a Potential Susquehanna Connector Trail for the John Smith Historic Trail Prepared for The Friends of the John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail November 16, 2009 Coordinated by The Bucknell University Environmental Center’sNature and Human Communities Initiative The Susquehanna Colloquium for Nature and Human Communities The Susquehanna River Heartland Coalition for Environmental Studies In partnership with Bucknell University The Eastern Delaware Nations The Haudenosaunee Confederacy The Susquehanna Greenway Partnership Pennsylvania Environmental Council Funded by the Conservation Fund/R.K. Mellon Foundation 2 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 Recommended Susquehanna River Connecting Trail................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 6 Staff ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Criteria used for Study................................................................................................................. 6 2. Description of Study Area, Team Areas, and Smith Map Analysis ...................................... 8 a. Master Map of Sites and Trails from Smith Era in Study Area........................................... 8 b. Study -

Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment

ORIGINAL REPORT Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment of Residential Lots Proposed on Part of Lots 2, 3, & 4, Concession 9 Part of Lots 2, 3, 4 & 5 Concession 8 Geographic Township of Radcliffe Township of Madawaska Valley County of Renfrew in northcentral Ontario. Report Author: Dave Norris Woodland Heritage Northwest 134 College St. Thunder Bay, ON P7A 5J5 p: (807) 632-9893 e: [email protected] Project Information Location: Lot 2 and 3 CON 8 and Lots 2 and 3 CON 9 of the Township of Madawaska Valley PIF P307-0077-2017 Proponent Information: Mr. Neil Enright National Fur Farms Inc. 118 Annie Mayhew Road Combermere, Ontario K0J 1L0 Tel: (480) 363-6558 E-Mail: [email protected] Report Completed: September 13, 2017 Report Submitted: October 1, 2017 Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment of Lots 2 and 3 CON8, Lots 2 and 3 CON 9 in the Township of Madawaska Valley, Township of Renfrew i © 2017 Woodland Heritage Northwest. All rights reserved. Executive Summary National Fur Farms Inc. in Combermere, Ontario contracted Woodland Heritage Services to conduct a Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment of their property located on Part of Lots 2, 3 and 4 CON 9 and Lots 2, 3, 4 and 5 CON 8 of the Township of Madawaska Valley, in the county of Renfrew in northcentral Ontario. The proponent is planning on subdividing the property into 60 residential lots. The archaeological assessment was undertaken in accordance with the requirements of the Ontario Heritage Act (R.S.O. 1990), the Planning Act, and the Standards and Guidelines for Consulting Archaeologists (2011). -

The Laurentian Great Lakes

The Laurentian Great Lakes James T. Waples Margaret Squires Great Lakes WATER Institute Biology Department University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Brian Eadie James Cotner NOAA/GLERL Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior University of Minnesota J. Val Klump Great Lakes WATER Institute Galen McKinley University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Atmospheric and Oceanic Services University of Wisconsin-Madison Introduction forests. In the southern areas of the basin, the climate is much warmer. The soils are deeper with layers or North America’s inland ocean, the Great Lakes mixtures of clays, carbonates, silts, sands, gravels, and (Figure 7.1), contains about 23,000 km3 (5,500 cu. boulders deposited as glacial drift or as glacial lake and mi.) of water (enough to flood the continental United river sediments. The lands are usually fertile and have States to a depth of nearly 3 m), and covers a total been extensively drained for agriculture. The original area of 244,000 km2 (94,000 sq. mi.) with 16,000 deciduous forests have given way to agriculture and km of coastline. The Great Lakes comprise the largest sprawling urban development. This variability has system of fresh, surface water lakes on earth, containing strong impacts on the characteristics of each lake. The roughly 18% of the world supply of surface freshwater. lakes are known to have significant effects on air masses Reservoirs of dissolved carbon and rates of carbon as they move in prevailing directions, as exemplified cycling in the lakes are comparable to observations in by the ‘lake effect snow’ that falls heavily in winter on the marine coastal oceans (e.g., Biddanda et al. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 155/Tuesday, August 11, 2020

48556 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 155 / Tuesday, August 11, 2020 / Notices CO 80205, telephone (303) 370–6056, SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Notice is Affairs; performed a skeletal and email [email protected], by here given in accordance with the dentition analysis on October 25, 1995. September 10, 2020. After that date, if Native American Graves Protection and Although the exact date or pre-contact no additional requestors have come Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), 25 U.S.C. period associated with this site is forward, transfer of control of the 3003, of the completion of an inventory unknown, as no reliable temporal human remains and associated funerary of human remains under the control of indictors were recovered or recorded, objects to The Tribes may proceed. the Bruce Museum, Greenwich, CT. The the Shorakapock site is well The Denver Museum of Nature & human remains were removed from the documented in the New York Science and the U.S. Department of Shorakapock Site in Inwood Hill Park, archeological and historical literature. Agriculture, Forest Service, Gila New York County, NY. Records from 17th and 18th century National Forest are responsible for This notice is published as part of the documents indicate at least five notifying The Tribes that this notice has National Park Service’s administrative settlements may been located within or been published. responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 near the Inwood Hill Park vicinity. According to The Cultural Landscape Dated: July 7, 2020. U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in this notice are the sole responsibility of Foundation, the site was inhabited by Melanie O’Brien, the Lenape tribe through the Manager, National NAGPRA Program. -

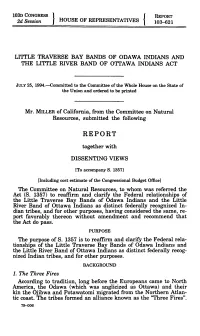

REPORT 2D Session HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES 103-621

103D CONGRESS } { REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 103-621 LITTLE TRAVERSE BAY BANDS OF ODAWA INDIANS AND THE LITTLE RIVER BAND OF OTrAWA INDIANS ACT JULY 25, 1994.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. MILLER of California, from the Committee on Natural Resources, submitted the following REPORT together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany S. 13571 [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Natural Resources, to whom was referred the Act (S.1357) to reaffirm and clarify the Federal relationships of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians as distinct federally recognized In- dian tribes, and for other purposes, having considered the same, re- port favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the Act do pass. PURPOSE The purpose of S. 1357 is to reaffirm and clarify the Federal rela- tionships of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians as distinct federally recog- nized Indian tribes, and for other purposes. BACKGROUND 1. The Three Fires According to tradition, long before the Europeans came to North America, the Odawa (which was anglicized as Ottawa) and their kin the Ojibwa and Potawatomi migrated from the Northern Atlan- tic coast. The tribes formed an alliance known as the "Three Fires". 79-006 The Ottawa/Odawa settled on the eastern shore of Lake Huron at what are now called the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island. In 1615, the Ottawa/Odawa formed a fur trading alliance with the French. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 179/Tuesday

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 179 / Tuesday, September 15, 2020 / Notices 57237 Band of Potawatomi Nation, Kansas); organizations and has determined that Community, Michigan; Keweenaw Bay Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior there is no cultural affiliation between Indian Community, Michigan; Lac Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin; Red the human remains and associated Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, funerary objects and any present-day Chippewa Indians of Michigan; Little Minnesota; Saginaw Chippewa Indian Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian River Band of Ottawa Indians, Tribe of Michigan; Sault Ste. Marie organizations. Representatives of any Michigan; Little Traverse Bay Bands of Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Michigan; Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian Odawa Indians, Michigan; Match-e-be- Shawnee Tribe; Sokaogon Chippewa organization not identified in this notice nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi Community, Wisconsin; St. Croix that wish to request transfer of control Indians of Michigan; Nottawaseppi Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin; of these human remains and associated Huron Band of the Potawatomi, Stockbridge Munsee Community, funerary objects should submit a written Michigan (previously listed as Huron Wisconsin; Turtle Mountain Band of request to Michigan State University. If Potawatomi, Inc.); Pokagon Band of Chippewa Indians of North Dakota; and no additional requestors come forward, Potawatomi Indians, Michigan and the Wyandotte Nation (hereafter referred transfer of control of the human remains Indiana; Saginaw Chippewa Indian to as ‘‘The Tribes’’). and associated funerary objects to the Tribe of Michigan; Sault Ste. Marie Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian Additional Requestors and Disposition Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Michigan; organizations stated in this notice may and two non-federally recognized Representatives of any Indian Tribes proceed.