Dr. Kate Masur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

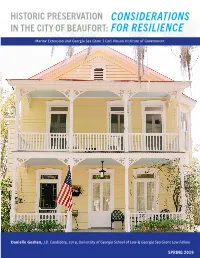

Considerations for Resilience Introduction

HISTORIC PRESERVATION CONSIDERATIONS IN THE CITY OF BEAUFORT: FOR RESILIENCE Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant | Carl Vinson Institute of Government Danielle Goshen, J.D. Candidate, 2019, University of Georgia School of Law & Georgia Sea Grant Law Fellow SPRING 2019 ABOUT THE AUTHORS DANIELLE GOSHEN, J.D. Candidate, will be graduating from the University of Georgia School of Law in 2019. During her time at Georgia Law she has served as a Georgia Sea Grant Legal Fellow. In addition, Danielle is an Editorial Board Member for the Journal of Intellectual Property Law and served as the President of the Environmental Law Association. Last summer Danielle interned at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 4 office in Atlanta. Special thanks goes to Rebecca Neubauer, Law Student, University of North Carolina School of Law & North Carolina Sea Grant and Heather Payne, Associate Professor at Seton Hall School of Law who provided background on national historic preservation laws in their paper: “Historical Preser- vation Laws and Long-Term Climate Change Adaptation: Challenges and Opportunities.” Additional thanks goes to Shana Jones, J.D., Director of the Georgia Sea Grant Law Program, for providing essential editing support as well as overall direction for the project and Sarah Watson, Coastal Climate and Resilience Specialist, S.C. Sea Grant Consortium and Carolinas Integrated Sciences and Assessments, and Professor Kirstin Dow, Carolina Trustees Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of South Carolina, for providing important feedback on this project. Cover Photo: Julia Engel, Gal Meets Glam PROJECT BACKGROUND his white paper is one outcome of a four-state regional project funded by the National Oceanic TAtmospheric Administration Office of Coastal Management, Florida Sea Grant, Georgia Sea Grant, South Carolina Sea Grant, and North Carolina Sea Grant (Project No.: FY2014-2018: NA14OAR4170084). -

Historic Preservation in the City of Beaufort, South Carolina: Considerations for Resilience

SEA GRANT LAW & POLICY JOURNAL VOL. 10:1 HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE CITY OF BEAUFORT, SOUTH CAROLINA: CONSIDERATIONS FOR RESILIENCE 1 Danielle Goshen I. INTRODUCTION: BEAUFORT, A HISTORIC “BEST SMALL TOWN” AT RISK The city of Beaufort, South Carolina is located on Port Royal Island, and is the state’s second oldest city. In 1711, the British founded Beaufort and the city was established as a shipbuilding center, before it became an agricultural hub during the antebellum period. During the Civil War, Beaufort was quickly occupied by the Union forces, and became an important terminus for previously enslaved people as they escaped plantations of the Confederacy.While the city has an estimated population of over 13,000,2 around 192,500 tourists visit Beaufort each year to soak in its rich history and enjoy the charming seaside scenery.3 In 1 Danielle Goshen, J.D., graduated from the University of Georgia School of Law in 2019. During her time at Georgia Law she has served as a Georgia Sea Grant Legal Fellow, an Editorial Board Member for the Journal of Intellectual Property Law, and as the President of the Environmental Law Association. Danielle also interned at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Region 4 office in Atlanta in the summer of 2018. This paper is one outcome of a four-state regional project funded by the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Florida Sea Grant, Georgia Sea Grant, South Carolina Sea Grant, and North Carolina Sea Grant, Project No.: FY2014-2018: NA14OAR4170084. Special thanks goes to Rebecca Neubauer, -

South Carolina Coastal Zone Management Act (Pt. 2

chapter IV -------------- special management areas A. GEOGRAPHIC AREAS OF PARTICULAR CONCERN 1. Introduction Statutory Requirements The Federal Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, while recognizing the entire coastal zone of each state as an important and vital resource, also declares that certain areas are of even more, special significance, and warrant particular attention to their preservation and development. The Act requires, in Section 305(B)(3), that each state inventory and designate the"Areas of Particular Concern" within its coastal zone as part of the state's program. Section 923.21 of the Coastal Zone Management Development and Approval Regulations (Federal Register, Vol. 44, No. 61, March 1979) defines the Federal requirements for Geographic Areas of Particular Concern (GAPCs). The subsection reads as follows: (a) Requirement. In order to meet the requirements of subsections 305(b) (3) & (5) of the Act, States must: (1) Designate geographic areas that are of particular concern, on a generic or site-specific basis or both; (2) Describe the nature of the concern and the basis on which designations are made; (3) Describe how the management program addresses and resolves the concerns for which areas are designated; and (4) Provide guidelines regarding priorities of uses in these areas, including guidelines on uses of lowest priority. The major emphasis in the GAPC segment of a coastal management program, from the Federal viewpoint, is on the adequacy of the State's authority to manage those areas or sites which have been identified. To a lesser extent, the reasons specific areas are significant as coastal resources and the criteria which establish this significance are also important for inclusion. -

CALHOUN COUNTY Fort Motte Vicinity

CONTENTS F I R S T T A B Acknowledgements 2015...................... 2 Foreword 2015 ..................................... 3 Acknowledgements 2008/2012 ............ 4 Foreword 2008/2012 ............................ 5 Introduction ......................................... 6 How to Use This Book ........................... 7 How to Interpret Entries ....................... 9 Map of Historical Sites by County ....... 10 S E C O N D T A B Historical Sites by County ................... 11 Abbeville 11 Aiken 11 Allendale 14 Anderson 14 Bamberg 15 Barnwell 15 Beaufort 16 Berkeley 25 Calhoun 28 Charleston 28 Cherokee 41 Chester 41 Chesterfield 42 Clarendon 43 Colleton 44 Darlington 45 Dillon 49 Dorchester 49 Edgefield 51 Fairfield 51 Florence 52 Georgetown 56 Greenville 60 Greenwood 63 Hampton 65 Horry 65 Jasper 67 Kershaw 67 Lancaster 69 Laurens 70 Lee 72 Lexington 72 Marion 72 Marlboro 74 Newberry 75 Oconee 76 Orangeburg 78 Pickens 84 Richland 85 Saluda 99 Spartanburg 99 Sumter 100 Union 101 Williamsburg 103 York 104 T H I R D T A B Academic Standards Introduction ..... 107 Teaching Activities ............................ 109 Lesson Plans ..................................... 133 F O U R T H T A B Places to Visit ................................... 213 Internet Resources ........................... 223 F I F T H T A B Indices .............................................. 227 Standard Indicator Index 227 Alphabetical Index 245 Time Period Index 253 Subject Index 259 Artwork: Temporary window coverings created by students from Benedict College, Claflin University, Columbia College, and the University of South Carolina for Bethel A.M.E. Church/Renaissance Cultural Arts Center Columbia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS - 2015 Edition he South Carolina African American Heritage Foundation South Carolina African American (SCAAHF) is very pleased to introduce the updated and Heritage Commission 2 T revised edition of A Teacher’s Guide to African American Board Members Historic Places in South Carolina. -

African American NHL Assessment Study

African American NHL Assessment Study National Park Service Organization of American Historians National Museum of African American History and Culture February 6, 2008 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………………………………………………1 BACKGROUND………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… 3 PART A. ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING THEMES…………………………………………………………….. 5 PART B. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL THEMES………..……………………………………. 7 PART C. FURTURE RESEARCH AND NOMINATION EFFORTS……..………………………………….. 10 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS…………...…………………………………………………………………………… 12 LIST OF APPENDICES APPENDIX A: AFRICAN AMERICAN NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS………….………….14 APPENDIX B: ANALYSIS OF AFRICAN AMERICAN NHLS………………………….…………….42 APPENDIX C: SCHOLAR COMPOSITE ASSESSMENT……………………………….………..… 45 APPENDIX D: NPS UNITS ASSOCIATED WITH AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY……………. 46 APPENDIX E: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EXISTING NHLs………..……………..…………..... 53 APPENDIX F: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POTENTIAL NHLs.…………..……………………... 57 APPENDIX G: ASSOCIATED THEME STUDIES………………..…………..………….………...…76 AFRICAN AMERICAN NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS ASSESSMENT STUDY National Park Service – Cultural Resources National Historic Landmarks Program EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction The African American National Historic Landmarks Assessment Study evaluated the National Historic Landmarks Program’s comprehensiveness in commemorating nationally significant African American history. The goal of the assessment study was to identify patterns in the identification, evaluation, and -

The Search for Planter the Ship That Escaped Charleston and Carried Robert Smalls to Destiny

The Search For Planter The Ship that Escaped Charleston and Carried Robert Smalls to Destiny May 2014 Bruce G. Terrell, Gordon P. Watts & Timothy J. Runyan National Marine Sanctuaries National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Maritime Heritage Program Series: Number 1 The Maritime Heritage Program works cooperatively and in collaboration within the Sanctuary System and with partners outside of NOAA. We work to better understand, assess and protect America’s maritime heritage and to share what we learn with the public as well as other scholars and resource managers. This is the first volume in a series of technical reports that document the work of the Maritime Heritage Program within and outside of the National Marine Sanctuaries. These reports will examine the maritime cultural landscape of America in all of its aspects, from overviews, historical studies, excavation and survey reports to genealogical studies. No. 1: The Search for Planter: The Ship That Escaped Charleston and Carried Robert Smalls to Destiny. No. 2: Archaeological Excavation of the Forepeak of the Civil War Blockade Runner Mary Celestia, Southampton, Bermuda No. 3: Maritime Cultural Landscape Overview: The Redwood Coast No. 4: Maritime Cultural Landscape Overview: The Outer Banks No. 5: Survey and Assessment of the U.S. Coast Survey Steamship Robert J. Walker, Atlantic City, New Jersey. These reports will be available online as downloadable PDFs and in some cases will also be printed and bound. Additional titles will become available as work on the series progresses. Cover Images - Robert Smalls: Library of Congress; Steamboat Planter: Naval History and Heritage Command; Map: NOAAs Historic Coast & Geodetic Survey Collection; Cover Collage: Matt McIntosh, ONMS Publication Design & Layout: Matt McIntosh, ONMS; Liz.Liang, ONMS The Search For Planter The Ship that Escaped Charleston and Carried Robert Smalls to Destiny May 2014 Bruce G. -

City of Beaufort Comprehensive Plan Update 2004 Table of Contents

City of Beaufort Comprehensive Plan Update 2004 Table of Contents City of Beaufort Comprehensive Plan Update 2004.................................................................... i CHAPTER ONE: DEMOGRAPHIC ELEMENT............................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................. 1 POPULATION .................................................................................................................................. 1 AGE DISTRIBUTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 RACIAL COMPOSITION AND TRENDS......................................................................................... 6 HOUSEHOLDS................................................................................................................................ 8 EDUCATION .................................................................................................................................... 8 INCOME......................................................................................................................................... 10 CONCLUSION: SUMMARY OF FINDINGS .................................................................................. 12 CHAPTER TWO: NATURAL RESOURCES ELEMENT .............................................................. 13 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... -

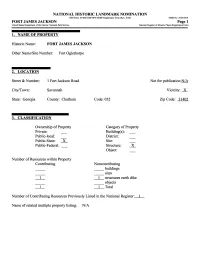

FORT JAMES JACKSON Other Name

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT JAMES JACKSON Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: FORT JAMES JACKSON Other Name/Site Number: Fort Oglethorpe 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1 Fort Jackson Road Not for publication:N/A City/Town: Savannah Vicinity: X State: Georgia County: Chatham Code: 052 Zip Code: 31402 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: __ Building(s): __ Public-local: __ District: __ Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: X Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ buildings ___ sites 1 structures earth dike ___ objects 1 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT JAMES JACKSON Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

FORT JAMES JACKSON Other Name

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT JAMES JACKSON Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: FORT JAMES JACKSON Other Name/Site Number: Fort Oglethorpe 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1 Fort Jackson Road Not for publication:N/A City/Town: Savannah Vicinity: X State: Georgia County: Chatham Code: 052 Zip Code: 31402 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: __ Building(s): __ Public-local: __ District: __ Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: X Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ buildings ___ sites 1 structures earth dike ___ objects 1 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT JAMES JACKSON Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Vv.' •,. . V -• •• ^|I§^ ''' ''' •••••'.:-I:' •'••••" ''' /: ..::X ;;; I':::;^^^^ .•

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR sfTrE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE South Carolina COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PL ACES Beaufort INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FDRNPruSE^NLY ENT.Ry NUMBER ' ^X DATE (Type all entries — complete applicable sect ions) &3</£<m\*>&DJ(f ^i/lli>1 |||liiliiiiii|;::|:t;::*:i|; f ^.i*» ®%j £ jff ^*mf^ " : .;•? = * W'- .= "::f v '^ :' ' '- ;;:::;:'::':::::::;;:;::;}:X:;:::;::*:'K:;ft::::i:::;;:::::i'!:^:|:x ;i:ll^£3?:W:V; •' '•*$& '- : *•' ^ : ' • '.^:': ' "". I :; COMMON: \ ' - i '^-'^ - ' \ Historic Beaufort \ —————————————————^-jfJi ————— », . •; •••« ——. ———= ——————t ———I ——————— AND/ OR HISTORIC: vv.' •,. V -• •• ^|i§^ ''' ''' •••••'.:-i:' •'••••" ''' /: ..::x ;;; i':::;^^^^ .•,. / .^-.£....... .:*)£$> STREETANDNUMBER: '"" v / ' ' ' '' Approximately 304 acres comprising the old City of BeaufTyrtr;" bounded by CITY B'ea'oTb'rt River, south and east; Hamar and Bladen Streets, west; Boundary St., north. STATE CODE; COUNTY: CODE South Carolina 41 Beaufort 07 [|^;:CLASSiFI^¥idN """ "::' : C TATIIC ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) STATUS TO THE PUBLIC [X] District Q Building CH Public Public Acqui sition: ffl Occupied ^ es: n Site Q Structure D Private D 1" P rocess Q Unoccupied 0 Restricted D Object S Both D Beir19 Considered Q Preservation work D Unrestricted in progress 1 — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) | | Agricultural j^] Government ^) Park | | Transportation 1 1 Comments (x! Commercial jg] Industrial ^) Private Res dence Q Other (Specify) [jj] Educational -

Sea Grant Law & Policy Journal

SEA GRANT LAW & POLICY JOURNAL SYMPOSIUM ISSUE INTRODUCTION Randall S. Abate WARMING OCEANS, COASTAL DISEASES, AND CLIMATE CHANGE PUBLIC Robin Kundis Craig HEALTH ADAPTATION GIRT BY SEA: ANTIPODEAN LESSONS IN COASTAL ADAPTATION LAW Jan McDonald ENVISIONING NATURE’S RIGHT TO A STABLE CLIMATE SYSTEM Grant Wilson HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE CITY OF BEAUFORT, SOUTH Danielle Goshen CAROLINA: CONSIDERATIONS FOR RESILIENCE SHORE PROTECTION FOR A SURE TOMORROW: EVALUATING COASTAL Julia M. Shelburne MANAGEMENT LAWS IN SEVEN SOUTHEASTERN STATES SEA GRANT LAW & POLICY JOURNAL VOLUME 10:1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SYMPOSIUM ISSUE INTRODUCTION Randall S. Abate WARMING OCEANS, COASTAL. .D . ISEASES. ,. AND. C. .LIMATE . C. .HANGE . P. UBLIC. .H . EALTH. .A . .DAPTATION . 1 Robin Kundis Craig GIRT BY SEA: ANTIPODEAN. L. .ESSONS . IN . C. .OASTAL . .A . DAPTATION. L. .AW . 3 Jan McDonald ENVISIONING NATURE. ’.S . R. .IGHT . TO . A. S. TABLE. .C . LIMATE. S. YSTEM. 29 Grant Wilson HISTORIC PRESERVATION. IN. THE . .C . ITY. OF. B. .EAUFORT . ,. S. .OUTH . C. .AROLINA . .: . C. .ONSIDERATIONS . FOR . .R . ESILIENCE. 60 Danielle Goshen 80 SHORE PROTECTION FOR. A. .S .URE . .T .OMORROW . :. .E .VALUATING . C. .OASTAL . .M . .ANAGEMENT . .L .AWS . IN. S. .EVEN . SOUTHEASTERN STATES Julia M. Shelburne 3 . 10 SEA GRANT LAW & POLICY JOURNAL VOLUME 10:1 MONMOUTH SYMPOSIUM EDITION EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Catherine Janasie EDITORIAL BOARD Donna Christie Blake Hudson Robin Craig Megan Mackey Ivy Frederickson Richard McLaughlin Don Gourlie Lisa Schiavinato Megan Herzog Ryan Stoa April 2020 NSGLC-20-01-01 SEA GRANT LAW & POLICY JOURNAL VOLUME 10:1 MONMOUTH SYMPOSIUM EDITION EDITOR’S NOTE Volume 10:1 of the Sea Grant Law & Policy Journal features articles from Monmouth University’s Climate Change, Coasts, and Communities” symposium on April 18, 2019.