South Carolina Coastal Zone Management Act (Pt. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

Winter/Spring 2013-2014

FRESPACE Findings Winter/Spring 2013/2014 President’s Report water is a significant shock to our animals and is a hindrance to our equipment cleaning efforts 2013 has certainly been a year of change for us: during maintenance. Susan Spell, our long serving ParkWinter 2008 Allocated $78 for FRESPACE to become Manager, left us early in the year to be near an ill a non-profit member of the Edisto Chamber of family member. This had consumed much of her Commerce. The Board feels that the expense is time over the previous year or so. We will miss justified based on the additional publicity EBSP her. and FRESPACE will receive from the Chamber’s Our new Park Manager, Jon Greider, many advertising initiatives. joined us during the summer. He has been most The ELC water cooler no longer works. helpful to us and we look forward to working The failure occurred during the recent hard with him. freeze. When the required repair is identified Our Asst. Park Manager, Jimmy “Coach” FRESPACE is prepared to help defray the costs. Thompson, retired late in Dec. He has always Authorized up to $150 to install pickets been there to help us and we are going to miss around the ELC rain barrels. Currently the “Coach”. barrels are unsightly and in a very visible area. Our new Asst. Park Manager, Brandon Goff, assumed his new duties shortly after the Our Blowhard team recently was in need of first of 2014. additional volunteers. Ida Tipton sent out an email Dan McNamee, our Interpretive Ranger blast from Bill Andrews, our Blowhard Team lead, over the last several years, left us in the early fall describing our needs as well as describing what to go to work at the Low Country Institute. -

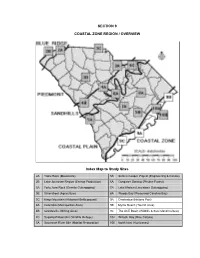

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

Edisto Beach Local Comprehensive Beach Management Plan 2017

TOWN OF EDISTO BEACH LOCAL COMPREHENSIVE BEACH MANAGEMENT PLAN 2017 Previous State Approved-February 1, 2012 Beachfront Management Committee Adoption-April 12, 2017 Local Adoption -October 12, 2017 State Approved- April 2, 2019 Prepared by Iris Hill Page 1 of 129 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 History of Plan Approvals and Revisions ............................................................................................. 6 1.3. Overview of Municipality ................................................................................................................... 6 1.3.1 Local Beach Management Policies ............................................................................................... 8 1.4 Local Beach Management Issues ........................................................................................................ 9 2. Inventory of Existing Conditions ......................................................................................................... 10 2.1 General Characteristics of the Beach ................................................................................................ 10 2.1.1 Land Use Patterns ..................................................................................................................... -

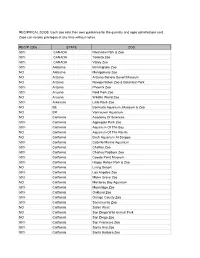

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

National Center for National Park Service NCPTT Preservation Technology and Training U.S. Department of the Interior Annual Report for the period October 1,1994 — September 30,1998 To the President and Congress NCPTT Purposes The Preservation Technology and Training Board is pleased to be part of a new and critically NCPTT has five legislated purposes — needed, initiative of the National Park Service — the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training. The opportunity to bring our varied professional experience to bear "(1) develop and distribute preservation and conservation skills and technologies for the on NCPTT's development — and to see so much accomplished in the first four years — has identification, evaluation, conservation, and interpretation of prehistoric and historic been both exciting and rewarding. This report describes important new work that has had resources; remarkable nationwide impact in a very short time — an accomplishment with which this advisory board is proud to be associated. "(2) develop and facilitate training for Federal, State and local resource preservation professionals, cultural resource managers, maintenance personnel, and others working in the preservation Dr. Elizabeth A. Lyon field; On behalf of the Preservation Technology and Training Board November 1998 "(3) take steps to apply preservation technology benefits from ongoing research by other agencies and institutions; Creating NCPTT "(4) facilitate the transfer of preservation technology among Federal agencies, State and local In the mid-1980s, the U.S. Congress, responding to decades of concern from the preservation governments, universities, international organizations, and the private sector; and community, commissioned its Office of Technology Assessment to examine the relationship between technology and the development of the national preservation industry. -

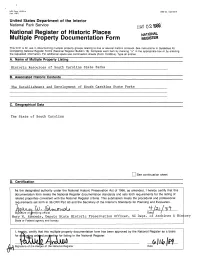

National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER

NFS Form 10-900-b . 0MB Wo. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ,.*v Q21989^ National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing________________________________________ Historic Resources of South Carolina State Parks________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ The Establishment and Development of South Carolina State Parks__________ C. Geographical Data The State of South Carolina [_JSee continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of gertifying official Date/ / Mary W. Ednonds, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer, SC Dept. of Archives & His tory State or Federal agency and bureau I, heceby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for ewalua|ing selaled properties for listing in the National Register. Signature of the Keeper of the National Register Date E. -

Waccamaw River Blue Trail

ABOUT THE WACCAMAW RIVER BLUE TRAIL The Waccamaw River Blue Trail extends the entire length of the river in North and South Carolina. Beginning near Lake Waccamaw, a permanently inundated Carolina Bay, the river meanders through the Waccamaw River Heritage Preserve, City of Conway, and Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge before merging with the Intracoastal Waterway where it passes historic rice fields, Brookgreen Gardens, Sandy Island, and ends at Winyah Bay near Georgetown. Over 140 miles of river invite the paddler to explore its unique natural, historical and cultural features. Its black waters, cypress swamps and tidal marshes are home to many rare species of plants and animals. The river is also steeped in history with Native American settlements, Civil War sites, rice and indigo plantations, which highlight the Gullah-Geechee culture, as well as many historic homes, churches, shops, and remnants of industries that were once served by steamships. To protect this important natural resource, American Rivers, Waccamaw RIVERKEEPER®, and many local partners worked together to establish the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, providing greater access to the river and its recreation opportunities. A Blue Trail is a river adopted by a local community that is dedicated to improving family-friendly recreation such as fishing, boating, and wildlife watching and to conserving riverside land and water resources. Just as hiking trails are designed to help people explore the land, Blue Trails help people discover their rivers. They help communities improve recreation and tourism, benefit local businesses and the economy, and protect river health for the benefit of people, wildlife, and future generations. -

New Discoveries D

NEWDISCOVERIES... By Gwen Thurmond and Joquita Burka At every turn in the road, every day of your visit to South 2,000 butterflies, moths and birds. The facility allows visitors Carolina, you’ll discover something new. It may be the to observe these living creatures interacting in a carefully newest restaurant, an “undiscovered” artist, a hidden garden reproduced natural habitat. or an artisan practicing in the “old ways.” This year’s discoveries The Butterfly Pavilion’s Nature Zone Discovery Center cover everything from butterflies to blacksmiths, sea turtles features live insects, reptiles, amphibians and arachnids. Visitors to showcase homes. No matter how many times you come to are transported to the mountains of Mexico surrounded by a South Carolina, you never find just exactly the same adventure. re-creation of towering fir trees and thousands of over wintering Monarch butterflies in a breathtaking sunrise BUTTERFLY PAVILION setting. The 22,500-square-foot Butterfly Pavilion, slated to open The Butterfly Conservatory, a glass structure towering 40 in the spring of 2001 at Broadway at the Beach in Myrtle feet, encompasses 9,000 square feet of lush landscape. Beach, is the first facility in the United States to incorporate a Thousands of native North American butterflies and moths fully enclosed glass conservatory featuring native North make their homes among carefully reproduced natural American butterflies. A fun-filled attraction and learning center habitats transformed into tropical, woodlands, cottage and for nature enthusiasts of all ages, Butterfly Pavilion features formal gardens. hands-on science exhibits and aviaries housing more than www.DiscoverSouthCarolina.com SOUTH CAROLINA AQUARIUM From the banks of the Bahamas to the seas of Argentina, Visitors to the Charleston area are discovering the South visitors will go underwater to meet Dolphins and get a new Carolina Aquarium, a $70-million science museum located perspective on their lives and remarkable intelligence. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

An Evolved Understanding: an Examination of the National

AN EVOLVED UNDERSTANDING: AN EXAMINATION OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE’S APPROACH TO THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AT CHATHAM MANOR, FREDERICKSBURG AND SPOTSYLVANIA NATIONAL MILITARY PARK A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Olivia Holly Heckendorf August 2019 © 2019 Olivia Holly Heckendorf ii ABSTRACT Chatham Manor became part of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park in December 1975 after the death of its last private owner, John Lee Pratt. Constructed between 1768 and 1771, Chatham Manor has always been intertwined with the landscape and has gained significance throughout its 250-year lifespan. With each subsequent owner and period of time Chatham Manor has gained significance as a cultural landscape. Since its acquisition in 1975, the National Park Service has grappled with the significance and interpretation of Chatham Manor as a cultural landscape. This thesis provides an analysis of the National Park Service’s ideas of significance and interpretation of the cultural landscape at Chatham Manor. This is done through a discussion of several interpretive planning documents and correspondences from the staff of the National Park Service, including interpretive prospectuses, a general management plan, and long-range interpretive plan. In addition, the influence of both superintendents and staff is taken into consideration. Through the analysis of these documents, it was realized that the understanding of cultural landscapes is continuing to evolve within the National Park Service. In the 1960s and 1970s Chatham Manor was considered significant and interpreted almost solely for its association with the Civil War. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history.