Hunger: Passion of the Militant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Counter-Aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing

Notes Chapter One Introduction: Taoibh Amuigh agus Faoi Ghlas: The Counter-aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing 1. Gerry Adams, “The Fire,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 37. 2. Ibid., 46. 3. Pat Magee, Gangsters or Guerillas? (Belfast: Beyond the Pale, 2001) v. 4. David Pierce, ed., Introduction, Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader (Cork: Cork University Press, 2000) xl. 5. Ibid. 6. Shiela Roberts, “South African Prison Literature,” Ariel 16.2 (Apr. 1985): 61. 7. Michel Foucault, “Power and Strategies,” Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980) 141–2. 8. In “The Eye of Power,” for instance, Foucault argues, “The tendency of Bentham’s thought [in designing prisons such as the famed Panopticon] is archaic in the importance it gives to the gaze.” In Power/ Knowledge 160. 9. Breyten Breytenbach, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983) 147. 10. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 4. 11. Ibid. 12. William Wordsworth, “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. 2A, 7th edition, ed. M. H. Abrams et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000) 250. 13. Gerry Adams, “Inside Story,” Republican News 16 Aug. 1975: 6. 14. Gerry Adams, “Cage Eleven,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 20. 15. Wordsworth, “Preface” 249. 16. Ibid., 250. 17. Ibid. 18. Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 27. 19. W. B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: Macmillan, 1961) 521–2. 20. Bobby Sands, One Day in My Life (Dublin and Cork: Mercier, 1983) 98. -

Module 2 Questions & Answers

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS LESSON 1 // CIVIL RIGHTS IN NORTHERN IRELAND 1. Which group were formed on 29th January 1967? Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). 2. Which group formed as a result of an incident on 5th October 1968? People’s Democracy. 3. a) Which act established the Northern Ireland Housing Executive and when was it passed? ry The Housing Executive Act, 25th February 1971. ra Lib ills (c) RTÉ St 3. b) Which act appointed a Boundaries Commissioner and what was their job? The Local Government Boundaries Act. The job of the Boundaries Commissioner was to recommend the boundaries and names of new district councils and ward areas. 4. Why may some members of the Catholic community have been outraged by the incident which resulted in a protest at Caledon on 20th June 1968? Student’s answers should highlight the allocation of a house to a young, single Protestant female ahead of older Catholic families. EXTENSION ACTIVITY 1 The Cameron Report was set up in January 1969 to look into civil disturbances in Northern Ireland. Looking at the key events, which events may have lead to the establishment of the report? Student’s answers should make mention of disturbances which followed the events of the 5th October 1968 and 1st January 1969. EXTENSION ACTIVITY 2 Below is a table which lists the demands of NICRA. Read through the list of reforms/acts and write down the name of the reform/act which addressed each demand. NICRA DEMANDS REFORM / ACT One man, one vote Electoral Law Act An end to gerrymandering – an end to the setting of -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

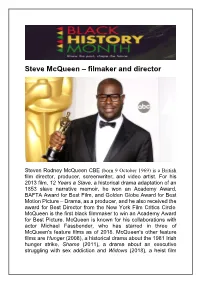

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

El Último Cine

Cartel alemán de Estambul 65 (Antonio Isasi Isasmendi, 1965). Bilbao (Bigas Luna, 1978) SuscripciónSuscripción a la a alertala alerta del del programa programa mensual mensual del del cine cine Doré Doré en: en: http://www.mcu.es/suscripciones/loadAlertForm.do?cache=init&layout=alertasFilmo&area=FILMO http://www.mcu.es/suscripciones/loadAlertForm.do?cache=init&layout=alertasFilmo&area=FILMO Ciclos en preparación: Marzo: William Wellman (y II) CiclosAño enDual preparación: España-Japón 3XDOC Febrero:Ellas crean: Nueve cineastas argentinas Muestra de cine filipino (y II) MuestraRecuerdo de cinede: Jesúsbúlgaro Franco, Alfredo Landa, Lolita Sevilla … CasaCentenario Asia presenta: de Rafael ‘El últimoGil (y II) cine iraní’ RecuerdoJirí Menzel de Maureen O´Hara Mikhail Romm Jirí Menzel Brian de Palma Alberto Lattuada Alberto Lattuada Luc Moullet GOBIERNO MINISTERIO DE ESPAÑA DE EDUCACIÓN, CULTURA Y DEPORTE ENERO 2016 Centenario de Harold Lloyd Robert Bresson Recuerdo de Vicente Aranda Costa-Gavras Muestra de cine filipino Muestra de cine palestino (y II) Muestra de cine rumano (y II) Costa-Gavras Mike de Leon rodando Itim (1976) Agradecimientos enero 2016: A Contracorriente Films, Barcelona; Antonio Isasi Jr., Barcelona; Cinemateca Portuguesa, Lisboa; Film Development Council of the Philippines (Briccio Santos, presidente, y Teodoro Granados, director ejecutivo), Makati; Flat Cinema, Madrid; Gaumont, Harold Lloyd Entertainment, Inc. (Sara Juárez), Los Ángeles; Instituto Cultural Rumano de Madrid (Ioana Anghel, Ovidiu Miron); Lola Films, Madrid; Multivideo S.L, Madrid; Oesterreichisches Filmmuseum (Regina Schlagnitweit ), Viena; Plataforma de Divulgación UCM (Ricardo Jimeno y José Antonio Jiménez de las Heras), Madrid; Tamasa Distribu- tion, París; Universal Pictures; Video Mercury, Madrid; Warner Bros. Pictures int. -

Directing the Narrative Shot Design

DIRECTING THE NARRATIVE and SHOT DESIGN The Art and Craft of Directing by Lubomir Kocka Series in Cinema and Culture © Lubomir Kocka 2018. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Cinema and Culture Library of Congress Control Number: 2018933406 ISBN: 978-1-62273-288-3 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. CONTENTS PREFACE v PART I: DIRECTORIAL CONCEPTS 1 CHAPTER 1: DIRECTOR 1 CHAPTER 2: VISUAL CONCEPT 9 CHAPTER 3: CONCEPT OF VISUAL UNITS 23 CHAPTER 4: MANIPULATING FILM TIME 37 CHAPTER 5: CONTROLLING SPACE 43 CHAPTER 6: BLOCKING STRATEGIES 59 CHAPTER 7: MULTIPLE-CHARACTER SCENE 79 CHAPTER 8: DEMYSTIFYING THE 180-DEGREE RULE – CROSSING THE LINE 91 CHAPTER 9: CONCEPT OF CHARACTER PERSPECTIVE 119 CHAPTER 10: CONCEPT OF STORYTELLER’S PERSPECTIVE 187 CHAPTER 11: EMOTIONAL MANIPULATION/ EMOTIONAL DESIGN 193 CHAPTER 12: PSYCHO-PHYSIOLOGICAL REGULARITIES IN LEFT-RIGHT/RIGHT-LEFT ORIENTATION 199 CHAPTER 13: DIRECTORIAL-DRAMATURGICAL ANALYSIS 229 CHAPTER 14: DIRECTOR’S BOOK 237 CHAPTER 15: PREVISUALIZATION 249 PART II: STUDIOS – DIRECTING EXERCISES 253 CHAPTER 16: I. -

When Art Becomes Political: an Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence History & Classics Undergraduate Theses History & Classics 12-15-2018 When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 Maura Wester Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons Wester, Maura, "When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011" (2018). History & Classics Undergraduate Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History & Classics at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in History & Classics Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 by Maura Wester HIS 490 History Honors Thesis Department of History and Classics Providence College Fall 2018 For my Mom and Dad, who encouraged a love of history and showed me what it means to be Irish-American. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………… 1 Outbreak of The Troubles, First Murals CHAPTER ONE …………………………………………………………………….. 11 1981-1989: The Hunger Strike, Republican Growth and Resilience CHAPTER TWO ……………………………………………………………………. 24 1990-1998: Peace Process and Good Friday Agreement CHAPTER THREE ………………………………………………………………… 38 The 2000s/2010s: Murals Post-Peace Agreement CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………… 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………… 63 iv 1 INTRODUCTION For nearly thirty years in the late twentieth century, sectarian violence between Irish Catholics and Ulster Protestants plagued Northern Ireland. Referred to as “the Troubles,” the violence officially lasted from 1969, when British troops were deployed to the region, until 1998, when the peace agreement, the Good Friday Agreement, was signed. -

Report on the Singing Detective25th Anniversary Symposium, University

JOSC 4 (3) pp. 335–343 Intellect Limited 2013 Journal of Screenwriting Volume 4 Number 3 © 2013 Intellect Ltd Conference Report. English language. doi: 10.1386/josc.4.3.335_7 Conference Report David Rolinson University of Stirling Report on The Singing Detective 25th Anniversary Symposium, University of London, 10 December 2011 [I]n keeping with the modernist sensibility and self-reflexivity of Hide and Seek and Only Make Believe, the decision to root a view of the past in the experiences and imagination of a writer protagonist, emphasises the fact that, far from being an objective assessment, any perspective on history can only ever be subjective. (Cook 1998: 217) This one-day symposium, organized by the Department of Media Arts at Royal Holloway, University of London, celebrated the 25th anniversary of Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective (tx. BBC1, 16 November 1986–21 December 1986). As the notes for the event explained, it sought to pay trib- ute to the BBC serial’s ‘narrative complexity, generic hybridity and formal experimentation’ and to bring scholars and practitioners together ‘to assess its subsequent influence upon television drama and the cinema’. This combination of academic and practitioner perspectives has been a welcome 335 JOSC_4.3_Conference Report_335-343.indd 335 7/19/13 9:56:44 PM David Rolinson 1. Although not feature of British television conferences in recent years, facilitating a reward- discussed on the day, biographical-auteurist ing exchange of ideas. This piece is, therefore, partly a report of the day’s approaches reward but proceedings but also a response to some of the many ideas that were raised by also imprison critics the interviews and presentations. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Lesley Sharp and the Alternative Geographies of Northern English Stardom

This is a repository copy of Lesley sharp and the alternative geographies of northern english stardom. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95675/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Forrest, D. and Johnson, B. (2016) Lesley sharp and the alternative geographies of northern english stardom. Journal of Popular Television, 4 (2). pp. 199-212. ISSN 2046-9861 https://doi.org/10.1386/jptv.4.2.199_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Lesley Sharp and the alternative geographies of Northern English Stardom David Forrest, University of Sheffield Beth Johnson, University of Leeds Abstract Historically, ‘North’ (of England) is a byword for narratives of economic depression, post-industrialism and bleak and claustrophobic representations of space and landscape.