Archaic Exploitation of Small Mammals and Birds in Northern Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Mountain Vizcacha (Lagidium Cf. Peruanum) in Ecuador

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Werner, Florian A.; Ledesma, Karim J.; Hidalgo B., Rodrigo Mountain vizcacha (Lagidium cf. peruanum) in Ecuador - First record of chinchillidae from the northern Andes Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 13, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2006, pp. 271-274 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Tucumán, Argentina Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45713213 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 13(2):271-274, Mendoza, 2006 ISSN 0327-9383 ©SAREM, 2006 Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 www.cricyt.edu.ar/mn.htm MOUNTAIN VIZCACHA (LAGIDIUM CF. PERUANUM) IN ECUADOR – FIRST RECORD OF CHINCHILLIDAE FROM THE NORTHERN ANDES Florian A. Werner¹, Karim J. Ledesma2, and Rodrigo Hidalgo B.3 1 Albrecht-von-Haller-Institute of Plant Sciences, University of Göttingen, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; <[email protected]>. 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, U.S.A; <[email protected]>. 3 Colegio Nacional Eloy Alfaro, Gonzales Suarez y Sucre, Cariamanga, Ecuador; <[email protected]>. Key words. Biogeography. Caviomorpha. Distribution. Hystricomorpha. Viscacha. Chinchillidae is a family of hystricomorph Cerro Ahuaca is a granite inselberg 2 km rodents distributed in the Andes of Peru, from the town of Cariamanga (1950 m), Loja Bolivia, Chile and Argentina, and in lowland province (4°18’29.4’’ S, 79°32’47.2’’ W). -

Plant Patterning in the Chilean Matorral: Are Ent Effects on the Matorral Vegetation

Abstract: Native and exotic mammals have differ- Plant Patterning in the Chilean Matorral: Are ent effects on the matorral vegetation. (A) Large the Roles of Native and Exotic Mammals mammals (guanacos vs goats) differ in that native 1 guanacos are only minor browsers, whereas goats Different? use shrubs more extensively. Differences between goats and shrub-defoliating insects provide addi- tional evidence that goats are a novel perturba- 2 tion on the matorral vegetation. (B) European Eduardo R. Fuentes and Javier A. Simonetti rabbits and their native counterparts differ in their effects on shrub seedlings and on native perennial herbs. Native small mammals affect only the periphery of antipredator refuges. Rabbits are infrequently preyed upon, do not exhibit such habitat restriction, and show a more extensive effect. Implications for matorral renewal are discussed. Mammals and the matorral vegetation have recip- tolerance to the new species. Here, only pre- rocal effects on each other's distribution and adaptative traits would account for any resilience abundance. On the one hand, shrubs, herbs, and of the system. grasses provide food and cover for matorral mam- mals (Jaksić and others 1980; see also the chapter The second reason why the question is important by W. Glanz and P. Meserve in this volume). On relates to the coupling of herbivores to the eco- the other hand, the use that mammals make of the system structure. habitat can have several consequences for the plants, affecting their distribution and abun- Herbivores as a link between producers and car- dance. nivores have been selected not only for their ca- pacity to eat tissues of certain plants but also Here, we will examine the question: are the for their ability to avoid predation. -

Dental Homologies and Evolutionary Transformations In

Dental homologies and evolutionary transformations in Caviomorpha (Hystricognathi, Rodentia): new data from the Paleogene of Peruvian Amazonia Myriam Boivin, Laurent Marivaux To cite this version: Myriam Boivin, Laurent Marivaux. Dental homologies and evolutionary transformations in Caviomor- pha (Hystricognathi, Rodentia): new data from the Paleogene of Peruvian Amazonia. Historical Biology, Taylor & Francis, 2020, 32 (4), pp.528-554. 10.1080/08912963.2018.1506778. hal-01870927 HAL Id: hal-01870927 https://hal.umontpellier.fr/hal-01870927 Submitted on 17 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Page 1 of 118 Historical Biology 1 2 3 Dental homologies and evolutionary transformations in Caviomorpha (Hystricognathi, 4 5 Rodentia): new data from the Paleogene of Peruvian Amazonia 6 7 8 9 10 a* a 11 Myriam Boivin and Laurent Marivaux 12 13 14 15 a Laboratoire de Paléontologie, Institut des Sciences de l’Évolution de Montpellier (ISE-M), c.c. 16 For Peer Review Only 17 18 064, Université de Montpellier, CNRS, IRD, EPHE, place Eugène Bataillon, F-34095 19 20 Montpellier Cedex 05, France. 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 *Corresponding author. -

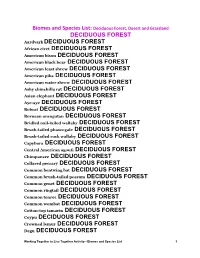

Deciduous Forest

Biomes and Species List: Deciduous Forest, Desert and Grassland DECIDUOUS FOREST Aardvark DECIDUOUS FOREST African civet DECIDUOUS FOREST American bison DECIDUOUS FOREST American black bear DECIDUOUS FOREST American least shrew DECIDUOUS FOREST American pika DECIDUOUS FOREST American water shrew DECIDUOUS FOREST Ashy chinchilla rat DECIDUOUS FOREST Asian elephant DECIDUOUS FOREST Aye-aye DECIDUOUS FOREST Bobcat DECIDUOUS FOREST Bornean orangutan DECIDUOUS FOREST Bridled nail-tailed wallaby DECIDUOUS FOREST Brush-tailed phascogale DECIDUOUS FOREST Brush-tailed rock wallaby DECIDUOUS FOREST Capybara DECIDUOUS FOREST Central American agouti DECIDUOUS FOREST Chimpanzee DECIDUOUS FOREST Collared peccary DECIDUOUS FOREST Common bentwing bat DECIDUOUS FOREST Common brush-tailed possum DECIDUOUS FOREST Common genet DECIDUOUS FOREST Common ringtail DECIDUOUS FOREST Common tenrec DECIDUOUS FOREST Common wombat DECIDUOUS FOREST Cotton-top tamarin DECIDUOUS FOREST Coypu DECIDUOUS FOREST Crowned lemur DECIDUOUS FOREST Degu DECIDUOUS FOREST Working Together to Live Together Activity—Biomes and Species List 1 Desert cottontail DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern chipmunk DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern gray kangaroo DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern mole DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern pygmy possum DECIDUOUS FOREST Edible dormouse DECIDUOUS FOREST Ermine DECIDUOUS FOREST Eurasian wild pig DECIDUOUS FOREST European badger DECIDUOUS FOREST Forest elephant DECIDUOUS FOREST Forest hog DECIDUOUS FOREST Funnel-eared bat DECIDUOUS FOREST Gambian rat DECIDUOUS FOREST Geoffroy's spider monkey -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Lagidium Viscacia) in the PATAGONIAN STEPPE

EFFECTS OF LANDSCAPE STRUCTURE ON THE DISTRIBUTION OF MOUNTAIN VIZCACHA (Lagidium viscacia) IN THE PATAGONIAN STEPPE By REBECCA SUSAN WALKER A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UMVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2001 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As this research spanned several years, several disciplines, and two continents, I have many, many people to thank. There are so many that I am quite sure I will inadvertently leave someone out, and I apologize for that. In Gainesville First of all, 1 would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Lyn Branch, for her untiring and inspiring mentoring, and her many, many hours of thoughtful reading and editing of numerous proposals and this dissertation. I also thank her for the financial support she provided in various forms during my Ph.D. program. Finally, I thank her for her incessant demand for rigorous science and clear writing. Dr. Brian Bowen got me started in molecular ecology and helped me to never lose faith that it would all work out. He also provided important input into several proposals and the data analysis. Dr. Bill Farmerie deciphered many molecular mysteries for me and helped make my dream of Lagidium microsatellite primers a reality. I thank him for his crucial guidance in developing the microsatellite primers, for the use of his lab, and for his eternal good humor. ii I thank the other members of my original committee, Dr. George Tanner, Dr. John Eisenberg, and Dr. Colin Chapman, for their guidance and input into various stages of the research over the years. -

Southern & Central Argentina

The stunning Hooded Grebe is a Critically Endangered species with a population below 800 individuals, and was only described new to science in 1974 (Dave Jackson, tour participant) SOUTHERN & CENTRAL ARGENTINA 21 NOVEMBER – 8/12 DECEMBER 2017 LEADER: MARK PEARMAN Seventy-six stunning Hooded Grebes at a new breeding colony on a remote Patagonian steppe lake was a mind-blowing experience. Now at fewer than 800 birds, from a global population of 5000 when first discovered in 1974, the species is currently classified as Critically Endangered. Many of the grebes were either sitting on eggs or nest-building, and we also had a pair display right infront of us, with typical synchronized neck-twisting, and unusual crest raising accompanied by a unique and almost magical windhorn chorus. Birdquest missed the species altogether in 2016, managed great looks in 2014, 2011 and notably of breeding birds in 2009 at what is now an unsuitable breeding lake. Put into perspective, we count ourselves very lucky at witnessing this lifetime experience. The grebes came nicely off the cusp of a long journey which began with a string of goodies in Córdoba including both Cordoba and Olrog’s Cinclodes, as well as Spot-winged Falconet, Blue-tufted Starthroat, the ! ! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Southern & Central Argentina 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com wonderful endemic Salinas Monjita, stunning Olive-crowned Crescentchest, delightful Black-and-chestnut Warbling Finch and one of South Americas rarest woodpeckers, the elusive Black-bodied Woodpecker. A brief incursion into southern Entre Rios province produced Stripe-backed Bittern, several White-naped Xenopsaris and fifteen Ringed Teal before we began our journey through Buenos Aires province. -

Biology of Caviomorph Rodents: Diversity and Evolution

Biology of Caviomorph Rodents: Diversity and Evolution EDITED BY Aldo I. Vassallo Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, UNMdP, Argentina. Daniel Antenucci Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, UNMdP, Argentina. Copyright© SAREM Series A Mammalogical Research Investigaciones Mastozoológicas Buenos Aires, Argentina ISBN: 9789879849736 SAREM - Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Av. Ruiz Leal s/n, Parque General San Martín. CP 5500, Mendoza, Argentina http://www.sarem.org.ar/ Directive Committee President: David Flores (Unidad Ejecutora Lillo, CONICET-Fundación Miguel Lillo, Tucumán, Argentina) Vicepresident: Carlos Galliari (Centro de Estudios Parasitológicos y de Vectores, CEPAVE-CONICET, La Plata, Argentina) Secretary: Agustín M. Abba (Centro de Estudios Parasitológicos y de Vectores, CEPAVE-CONICET, La Plata, Argentina) Treasurer: María Amelia Chemisquy (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, MACN-CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina) Chairperson: Gabriel Martin (Centro de Investigaciones Esquel de Montaña y Estepa Patagónicas (CONICET-Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Esquel, Chubut, Argentina) and Javier Pereira (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, MACN-CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina) Alternate Chairperson: Alberto Scorolli (Universidad Nacional del Sur, Bahía Blanca, Buenos Aires, Argentina) Auditors: Marcela Lareschi (Centro de Estudios Parasitológicos y de Vectores, CEPAVE-CONICET, La Plata, Argentina) E. Carolina Vieytes (Museo de La Plata, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina) -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12. -

Small Animals for Small Farms

ISSN 1810-0775 Small animals for small farms Second edition )$2'LYHUVLÀFDWLRQERRNOHW Diversification booklet number 14 Small animals for small farms R. Trevor Wilson Rural Infrastructure and Agro-Industries Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome 2011 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-107067-3 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support -

Notes on the Taxonomy of Mountain Viscachas of the Genus Lagidium Meyen 1833 (Rodentia: Chinchillidae)

THERYA, 2017, Vol. 8 (1): 27 - 33 DOI: 10.12933/therya-17-479 ISSN 2007-3364 Notes on the taxonomy of mountain viscachas of the genus Lagidium Meyen 1833 (Rodentia: Chinchillidae) PABLO TETA*1 AND SERGIO O. LUCERO1 1 División Mastozoología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia” Avenida Ángel Gallardo 470, C1405DJR. Buenos Aires, Argentina. E-mail [email protected] (PT), [email protected] (SOL) * Corresponding author Mountain viscachas of the genus Lagidium Meyen 1833 are medium-to-large hystricomorph rodents (1.5 -- 3 kg) that live in rocky outcrops from Ecuador to southern Argentina and Chile. Lagidium includes more than 20 nominal forms, most of them based on one or two individuals, which were first described during the 18th and 20th. Subsequent revisions reduced the number of species to three to four, depending upon the author. Within the genus, Lagidium viscacia (Molina, 1782) is the most widely distributed species, with populations apparently extended from western Bolivia to southern Argentina and Chile. We reviewed > 100 individuals of Lagidium, including skins and skulls, most of them collected in Argentina. We performed multivariate statistical analysis (i. e., principal component analysis [PCA], discriminant analysis [DA]) on a subset of 55 adult individuals grouped according to their geographical origin, using 16 skull and tooth measurements. In addition, we searched for differences in cranial anatomy across populations. PCA and DA indicate a moderate overlap between individuals from southern Argentina, on one hand, and northwestern Argentina, western Bolivia and northern Chile, on the other. The external coloration, although variable, showed a predominance of gray shades in southern Argentina and yellowish gray in northwestern Argentina. -

The Case of the Viscacha (Lagidium Viscacia, Chinchillidae)

Urban Ecosyst (2014) 17:163–172 DOI 10.1007/s11252-013-0314-3 Can a habitat specialist survive urbanization? the case of the viscacha (Lagidium viscacia, Chinchillidae) Francisco E. Fontúrbel & Teresa Tarifa Published online: 7 May 2013 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 Abstract Urban growth is a strong driver of habitat degradation and loss. In spite of that, a surprising diversity of native species may survive in urban areas. In the La Paz, Bolivia metropolitan area and surroundings, local populations of “viscachas” (Lagidium viscacia) currently survive in small, isolated habitat patches. We assessed 13 study sites in 1999, 2003, and 2007 to document the effects of urban growth on L. viscacia habitats. Degree of disturbance at the study sites increased more between 1999 and 2003 than it did between 2003 and 2007 due to patterns of urban expansion. Using satellite imagery we determined that the urban area increased 566 ha (from 1987 to 2001) mostly due to southward urban area expansion down the valley where the best viscacha habitats were located. Occupied patch area decreased 74 % between 1999 and 2007, accompanied by significant increases in patch edge-to-area ratios. Currently L. viscacia populations in La Paz are experiencing a habitat attrition process. If a current urban expansion plan for La Paz is approved, about 75 % of the remaining habitat may be lost to urban development in a short time, compromising the future viability of this species in the metropolitan area and surroundings. Environmental regula- tions to control urban growth of the La Paz metropolitan area are urgently required and constitute the only hope for the survival of L.