Single-Entity and North American Soccer's Struggle for Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Fire

Chicago Fire John Bankston 2001 SW 31st Avenue Hallandale, FL 33009 2001 SW 31st Avenue www.mitchellane.com Hallandale, FL 33009 www.mitchellane.com Copyright © 2019 by Mitchell Lane Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Printing 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Designer: Ed Morgan Editor: Sharon F. Doorasamy Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bankston, John, 1974- author Title: Chicago Fire / by John Bankston. Description: Hallandale, FL : Mitchell Lane Publishers, 2019. | Series: Major League Soccer | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018003124| ISBN 9781680202441 (library bound) | ISBN 9781680202458 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Chicago Fire (Soccer team)—History—Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC GV943.6.C45 B36 2018 | DDC 796.334/6477311—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003124 PHOTO CREDITS: Design Elements, freepik.com, Cover Photo: Jonathan Daniel/Getty Images, p. 5 © Ralph Morris CC-BY-SA-2.0, p. 6 public domain, p. 7 Shaun Botterill/ALLSPORT Getty Images, p. 8 Jonathan Daniel/ALLSPORT Getty Images, p. 11 Christopher Ruppel/Getty Images, p. 13 Doug Pensinger/Getty Images, p. 14 Jonathan Daniel/Getty Images, p. 17 freepik.com, p. 18 Jonathan Daniel/Getty Images, p. 21 Jonathan Daniel/MLS via Getty Images, p. 22 Stephen Dunn/Getty Images, p. 25 freepik.com, p. 27 Dylan Buell/Getty Images Contents Chapter One No More Sting ............................................................................... -

Bateman Tops GOP Ballot in Borough Vote

Your Want Ad T iui /ip Code Is Easy To Place • ' \i iiintninv') Just Phone 686 7700 0709? An OHicial For The Botnuqh Of Mountainside VOL. 19-NO. 27 Paid „. M,,,, MOUNTAINSIDE, N.J.. THURSDAY, JUNE 9, 1977 Bateman tops GOP ballot in borough vote Kirn hulls I'l'tileslfl tjliln'i i I , 1111 r i; 11 "VMthpr 'hr Rrpuhhr-an nur 'hr laces, (in hold «i(ies. of the l>;illni [ iiMiiori a! \r r;i nduiate*, for Si i'*' Scnah tailed In bring an appn>eiahl<- numbe; liii'i-H.itn chiilli'ngerv (iiir •.hmH.ird of Mountainside voters tu the polU in bearer t'eier MeDnnoiigh wun 701 Tuesday's primary election Of the borough voles, while Pemocr.iiH broii^ih •-. \ 'li\f\ rejJiMered vuh ~ri- ..nU li'ipclu! Hairs I'appii"- h;>'l I <7 SH'i J4 percent i easi hallols I berc aK" s>**re no > .uiir^K in In the battle fop nnminalion ,is the r i, i it i ma! ion** l<w (r<>m>ral \^Msmbl\ Republican gubernatorial nominee c aiiciidat!1^ Tnilit's u**re Raymond II Balenian uas the victor in Republicans William Magwir'1 I'M the hiirniigh liver challenger Thomas m,I I),,ivilH IiiFranrescMi i\7 7 Kean. by a vole of 4:i7 to :i"ti Totals for (Continued on page 21 the other ( K i|' hopefuls were (' Rohcri Sareone. 117 and William Angus ,Ir , '.M In the Democratic race, local setters gave their support to incumbent Dayton High Brendan Byrne, with 111 votes Robert A Hoe ssas second, svith TH voles, followed by Joseph A Hoffman. -

2016 Women's Lacrosse Guide

SHELBY MILNE BECKY CONTO LINDSEY ALFANO HOFSTRA 2016 WOMEN’S LACROSSE GUIDE AUDREY BYRD ALEXIS GREENE MORGAN KNOX TIANA PARRELLA HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY QUICK FACTS Location: Hempstead, New York 11549 Senior Sports Information Director: Founded: 1935 Jim Sheehan TABLE OF Enrollment: 10,870 Office Phone: (516) 463-6764 Affiliation: NCAA Division I Senior Assistant Director of Athletic CONTENTS Conference: Colonial Athletic Association Communications: Brian Bohl Nickname: Pride Office Phone: (516) 463-6759 Gold, White and Blue Colors: Director of Athletic Publications: Quick Facts 1 Home Field: James M. Shuart Stadium (13,000) Len Skoros (516) 463-5274 Press Box Phone: Office Phone: (516) 463-4602 Hofstra at a Glance 2 Stuart Rabinowitz President: Senior Reflections 4 Athletic Trainer for Women’s Lacrosse: Faculty Athletics Representative: Bobby DiMonda Dr. Michael Barnes Head Coach Shannon Smith 6 Strength and Conditioning Coach for Vice President and Director of Athletics: Jeffrey A. Hathaway Women’s Lacrosse: James Prendergast Associate Head Coach Katie Mollot 8 Deputy Director of Athletics: Equipment Manager for Women’s Dino Mattessich Lacrosse: John Considine Assistant Coach Michael Bedford 9 Secretary for Women’s Lacrosse: Senior Associate Director of Athletics: Support Staff 10 Cindy Lewis Cathy Aull Zack Lane, Brian Ballweg Senior Associate Director of Athletics for Photographers: 2016 Roster 11 Facilities: Jay Artinian and Jeff Mills Associate Director of Athletics for 2016 Outlook 12 Communications: Stephen Gorchov WOMEN’S LACROSSE -

Major League Soccer-Historie a Současnost Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra sportovních her Major League Soccer-historie a současnost Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Pavel Vacenovský Zdeněk Bezděk TVS/Trenérství Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brně dne 24. května 2013 podpis Děkuji vedoucímu bakalářské práce Mgr. Pavlu Vacenovskému, za podnětné rady, metodické vedení a připomínky k této práci. Úvod ........................................................................................................................ 6 1. FOTBAL V USA PŘED VZNIKEM MLS .................................................. 8 2. PŘÍPRAVA NA ÚVODNÍ SEZÓNU MLS ............................................... 11 2.1. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 17. října 1995..................................... 12 2.2. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 18. října 1995..................................... 14 2.3. První sponzoři MLS ............................................................................... 15 2.4. Platy Marquee players ............................................................................ 15 2.5. Další události v roce 1995 ...................................................................... 15 2.6. Drafty MLS ............................................................................................ 16 2.6.1. 1996 MLS College Draft ................................................................. 17 2.6.2. 1996 MLS Supplemental Draft ...................................................... -

MLS Game Guide

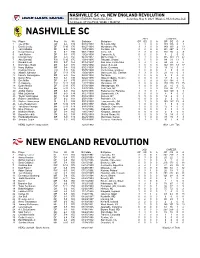

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Ottawa Fury Fc @ Tampa Bay Rowdies

TAMPA BAY ROWDIES OTTAWA FURY FC - VS – USL REGULAR SEASON April 8, 2017 7:30PM ET 2017 Record (W-D-L) & Conference Ranking: Al Lang Stadium, th 2017 Record (W-D-L) & Conference Ranking: 0-0-1 | 0 Point | 12 Place | 2GF 3GA st St. Petersburg, FL 2-0-0 | 6 Points | 1 Place | 5GF 0GA HOW TO WATCH AND LISTEN: TV: Rogers TV (Local) Channels: 22 (SD) & 182 (HD) | RADIO (EN): TSN 1200 | TSN1200.ca STREAM: USL Match Centre | SOCIAL MEDIA: LIVE updates on Twitter @OttawaFuryFC MATCH NOTES: Weekly Storylines: Fury FC dropped a hard-fought 3-2 decision in their USL opener last Saturday in St. Louis. Despite overturning a two-goal deficit, a late Saint Louis FC goal thwarted Ottawa’s comeback Saturday’s match marks the first time that Ottawa and Tampa Bay meet in USL action. The two sides have squared off nine times in NASL action. Fury FC is 2W-5D-2L lifetime versus the Rowdies Ottawa-native Eddie Edward and Onua Obasi notched their first-ever goals in Fury colours in Saturday’s loss. Edward’s goal was Ottawa’s first-ever goal in USL play Ottawa will be without the services of Shane McEleney who received a red card late in Saturday’s match The Rowdies sit atop the Eastern Conference with six points having outscored the opposition 5-0 Striker Georgi Hristov is among the league-leaders with two goals this season. Former Fury FC defender Kyle Porter is now a member of the Tampa Bay Rowdies Scouting the Rowdies: Tampa Bay finished ninth in the NASL last year with a combined record of 9W-12D-11L. -

2017 United Soccer League Media Guide

Table of Contents LEAGUE ALIGNMENT/IMPORTANT DATES ..............................................................................................4 USL EXECUTIVE BIOS & STAFF ..................................................................................................................6 Bethlehem Steel FC .....................................................................................................................................................................8 Charleston Battery ......................................................................................................................................................................10 Charlotte Independence ............................................................................................................................................................12 Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC .......................................................................................................................................14 FC Cincinnati .................................................................................................................................................................................16 Harrisburg City Islanders ........................................................................................................................................................18 LA Galaxy II ..................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

The Soccer Diaries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters Spring 2014 The oS ccer Diaries Michael J. Agovino Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Agovino, Michael J., "The ocS cer Diaries" (2014). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 271. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/271 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. the soccer diaries Buy the Book Buy the Book THE SOCCER DIARIES An American’s Thirty- Year Pursuit of the International Game Michael J. Agovino University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London Buy the Book © 2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska Portions of this book originally appeared in Tin House and Howler. Images courtesy of United States Soccer Federation (Team America- Italy game program), the New York Cosmos (Cosmos yearbook), fifa and Roger Huyssen (fifa- unicef World All- Star Game program), Transatlantic Challenge Cup, ticket stubs, press passes (from author). All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Agovino, Michael J. The soccer diaries: an American’s thirty- year pursuit of the international game / Michael J. Agovino. pages cm isbn 978- 0- 8032- 4047- 6 (hardback: alk. paper)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5566- 1 (epub)— isbn 978-0-8032-5567-8 (mobi)— isbn 978- 0- 8032- 5565- 4 (pdf) 1. -

Chastain, Dooley, Doyle, Harkes, Kraft, Mankameyer, Messersmith

MINUTES UNITED STATES SOCCER FEDERATION, INC. BOARD OF DIRECTOR’S MEETING TELEPHONE CONFERENCE JANUARY 10, 2007 5:00 P.M. CENTRAL TIME ______________________________________________________________________________ VIA TELEPHONE: Sunil Gulati, Mike Edwards, Bill Goaziou, Bill Bosgraaf, Paul Caligiuri, Dr. S. Robert Contiguglia, Daniel Flynn, Don Garber, Burton Haimes, Linda Hamilton, Brooks McCormick, Mike McDaniel, Larry Monaco, Kevin Payne. REGRETS: Peter Vermes. IN ATTENDANCE: Jay Berhalter, Timothy Pinto, Gregory Fike, Asher Mendelsohn. ______________________________________________________________________________ President Gulati called the meeting to order at 5:00 p.m. Asher Mendelsohn took roll call and announced that a quorum was present. PRESIDENT’S/SECRETARY GENERAL’S REPORT Dan Flynn updated the Board regarding the negotiation of the split between SUM and U.S. Soccer of television revenues. He also informed the Board that there was an agreement in principle with SUM. President Gulati informed the Board that there had been negotiations with MNT interim coach Bob Bradley regarding the terms to which he might be named the permanent MNT coach. He also told the Board that U.S. Soccer needed an update of the progress on creating a Women’s Professional Soccer League by the 2007 AGM. He emphasized that it is important to FIFA that the league be structured and supported in such a way that guarantees that the league will succeed for the long-term. TREASURER’S REPORT Bill Goaziou informed the Board that U.S. Soccer is in a strong financial position. UNFINISHED BUSINESS Tim Pinto updated the Board regarding the fact that the U.S. Futsal Federation was removed as a member of U.S. -

Philly and the US Open Cup Final Posted by Ed Farnsworth on August 13, 2014 at 12:15 Pm

PHILADELPHIA SOCCER HISTORY / US OPEN CUP Philly and the US Open Cup Final Posted by Ed Farnsworth on August 13, 2014 at 12:15 pm Featured image: The Bethlehem Steel FC victory float after winning their second US Open Cup, then known as the National Challenge Cup, on May 6, 1916. (Photo: University Archives & Special Collections Department, Lovejoy Library, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville) Philadelphia teams, both amateur and professional, have a long history of appearances in the final of America’s oldest soccer competition, winning the US Open Cup ten times. The last Philadelphia team to do so was the Ukrainian Nationals in 1966. At PPL Park on Sept. 16 at 7:30 pm, the Philadelphia Union will look to restart that winning tradition. Before the US Open Cup Before the founding of the US Open Cup in the 1913–1914 season, the claim for a national soccer title was held by the American Cup competition, also known as the American Football Association Cup and the American Federation Cup. First organized by the American Football Association in 1885, the competition primarily featured teams from the early American soccer triangle of Northern New Jersey, Southern New York and lower New England. In 1897, the John A. Manz team became the first Philadelphia club to win the American Cup. Tacony won in 1910 with Philadelphia Hibernian losing in the final the following year. In 1914, Bethlehem Steel FC won the first of its six American Cup titles by beating Tacony, who had also lost to Northern New Jersey’s Paterson True Blues in the final the year before. -

UCLA Athletics

UCLA - No. 1 Producer of Pro Talent Once again proving it is one of the top producers of soccer talent, Carlos UCLA had a league-high 23 former athletes on Major League Soccer Bocanegra UCLA’s MLS Draft History (MLS) rosters in 2012, including 2012 fi rst-round draft picks Kelyn Yr. Player Team Rd./overall Rowe and Chandler Hoffman. 1996 Billy Thompson# Columbus 3rd/21 Jorge Salcedo# Los Angeles 3rd/24 Overall, 66 Bruins have played in MLS in the league’s 18 years of Frankie Hejduk# Tampa Bay 7th/67 existence, more than any other school in the nation by far. Every Tayt Ianni# Tampa Bay 8th/77 starting UCLA goalkeeper from 1990-2003 played in the league. John O’Brien# Los Angeles 11th/104 Some of the most successful MLS players came from UCLA, includ- Paul Caligiuri* Columbus 1st/10 ing 2009 MLS Cup MVP Nick Rimando, 2006 MLS Rookie of the Zak Ibsen* New England 3rd/26 Adam Frye Tampa Bay 1st/4 Year Jonathan Bornstein, 2005 Defender of the Year Jimmy Conrad, Chris Snitko Kansas City 1st/5 two-time Defender of the Year and 2000 Rookie of the Year Carlos Greg Vanney Los Angeles 2nd/17 Bocanegra, 1999 MLS Goalkeeper of the Year Kevin Hartman, and Eddie Lewis San Jose 3rd/23 1997 Goalkeeper of the Year Brad Friedel. Ante Razov Los Angeles 3rd/27 UCLA alumni have won MLS titles in each of the last nine years with 1997 Tahj Jakins Colorado 1st/1 a total of 26 former Bruins winning the MLS Cup all-time - Kyle Kevin Hartman Los Angeles 3rd/29 Sam George* New England 3rd/22 Nakazawa, Brian Perk, Brian Rowe, Michael Stephens with the LA Galaxy in