The Soccer Diaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ticket Sales Report

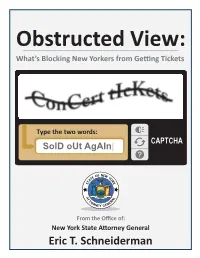

Obstructed View: What’s Blocking New Yorkers from Geng Tickets Type the two words: CAPTCHA SolD oUt AgAIn| From the Office of: New York State Aorney General Eric T. Schneiderman 1 This report was a collaborative effort prepared by the Bureau of Internet and Technology and the Research Department, with special thanks to Assistant Attorneys General Jordan Adler, Noah Stein, Aaron Chase, and Lydia Reynolds; Director of Special Projects Vanessa Ip; Researcher John Ferrara; Director of Research and Analytics Lacey Keller; Bureau of Internet and Technology Chief Kathleen McGee; Chief Economist Guy Ben-Ishai; Senior Enforcement Counsel and Special Advisor Tim Wu; and Executive Deputy Attorney General Karla G. Sanchez. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................... 3 The History of, and Policy Behind, New York’s Ticketing Laws ....... 7 Current Law ................................................................................... 9 Who’s Who in the Ticketing Industry ........................................... 10 Findings ....................................................................................... 11 A. The General Public Loses Out on Tickets to Insiders and Brokers .................................................................... 11 1. The Majority of Tickets for Popular Concerts Are Not Reserved For the General Public .......................................................................... 11 2. Brokers & Bots Buy Tickets in Bulk, Further Crowding Out Fans ...... 15 -

Download Chauffeur Application

All Transportation Network Inc. 800-525-2306 Chauffeur Application Full Name ______________________________ Phone # ________________________________ Present Address _________________________ Social Security # _________________________ City, State, Zip _________________________ Date of Birth ____________________________ Driver's License # ________________________ Class of License & Endorsements ___________ Availability Part Time _____________ Full Time ____________ Please specify schedule available to work: Weekdays (Monday-Friday) ______________________________________________________________ Weekends (Saturday-Sunday) ____________________________________________________________ If hired, what day will you be available to start? _______________________________________________ Have you been convicted of a crime or felony within the last 5 years? Yes ______ No _______ If yes, please explain the conviction: ________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ (The existence of a criminal record does not create an automatic barrier to employment) Have you had any accidents in the last 5 years? Yes ______ No _______ If yes, please explain: __________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ Have you had received any tickets in the last 5 years? Yes ______ No _______ If yes, please explain: __________________________________________________________________ -

2016 Women's Lacrosse Guide

SHELBY MILNE BECKY CONTO LINDSEY ALFANO HOFSTRA 2016 WOMEN’S LACROSSE GUIDE AUDREY BYRD ALEXIS GREENE MORGAN KNOX TIANA PARRELLA HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY QUICK FACTS Location: Hempstead, New York 11549 Senior Sports Information Director: Founded: 1935 Jim Sheehan TABLE OF Enrollment: 10,870 Office Phone: (516) 463-6764 Affiliation: NCAA Division I Senior Assistant Director of Athletic CONTENTS Conference: Colonial Athletic Association Communications: Brian Bohl Nickname: Pride Office Phone: (516) 463-6759 Gold, White and Blue Colors: Director of Athletic Publications: Quick Facts 1 Home Field: James M. Shuart Stadium (13,000) Len Skoros (516) 463-5274 Press Box Phone: Office Phone: (516) 463-4602 Hofstra at a Glance 2 Stuart Rabinowitz President: Senior Reflections 4 Athletic Trainer for Women’s Lacrosse: Faculty Athletics Representative: Bobby DiMonda Dr. Michael Barnes Head Coach Shannon Smith 6 Strength and Conditioning Coach for Vice President and Director of Athletics: Jeffrey A. Hathaway Women’s Lacrosse: James Prendergast Associate Head Coach Katie Mollot 8 Deputy Director of Athletics: Equipment Manager for Women’s Dino Mattessich Lacrosse: John Considine Assistant Coach Michael Bedford 9 Secretary for Women’s Lacrosse: Senior Associate Director of Athletics: Support Staff 10 Cindy Lewis Cathy Aull Zack Lane, Brian Ballweg Senior Associate Director of Athletics for Photographers: 2016 Roster 11 Facilities: Jay Artinian and Jeff Mills Associate Director of Athletics for 2016 Outlook 12 Communications: Stephen Gorchov WOMEN’S LACROSSE -

REFERENZEN WELTWEIT REFERENCE SITES WORLDWIDE Nationalstadion, Warschau Tour First, Courbevoie National Stadium Warsaw Tour First, Courbevoie

REFERENZEN WELTWEIT REFERENCE SITES WORLDWIDE Nationalstadion, Warschau Tour First, Courbevoie National Stadium Warsaw Tour First, Courbevoie O2 World, Berlin O2 World, Berlin Schlosshotel Lerbach, Bergisch Gladbach National Exhibition Center, Abu Dhabi Schlosshotel Lerbach, Bergisch Gladbach National Exhibition Center, Abu Dhabi DAS UNTERNEHMEN THE COMPANY 04 WILLKOMMEN BEI DEN EXPERTEN FÜR GESUNDES RAUMKLIMA WELCOME TO THE HOME OF THE EXPERTS FOR A HEALTHY INDOOR ENVIRONMENT WOLF REFERENZEN WELTWEIT WOLF REFERENCE WORLDWIDE 06 HEIZ-, KLIMA- UND LÜFTUNGSSYSTEME HEATING-, AIR HANDLING- AND VENTILATION SYSTEMS 08 HOTELS & GASTRONOMIE HOTELS & GASTRONOMY 10 KLINIKEN HOSPITALS 13 EINKAUFSZENTREN SHOPPING CENTERS 15 BANKEN BANKS 16 SCHULEN & UNIVERSITÄTEN SCHOOLS & UNIVERSITIES 18 BÜROS OFFICES 20 VERWALTUNGSGEBÄUDE ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES 22 HANDEL & GEWERBE COMMERCE & TRADE 24 PRODUKTIONSSTÄTTEN / FABRIKEN National Exhibition Center, Abu Dhabi PRODUCTION FACILITIES National Exhibition Center, Abu Dhabi 28 RECHENZENTREN DATA CENTERS 29 WOHNUNGSBAU HOUSING 30 AUTOHÄUSER CAR DEALERSHIPS 31 FLUGHÄFEN / BAHNHÖFE AIRPORTS / RAILWAY STATIONS 32 KULTURELLE EINRICHTUNGEN CULTURAL FACILITIES 33 FREIZEITZENTREN RECREATIONAL CENTERS 34 STADIEN & ARENEN SPORTS FACILITIES 36 GESUNDHEITSZENTREN / PRAXEN HEALTH CENTERS / PRACTICES 37 SONSTIGE EINRICHTUNGEN OTHER FACILITIES 38 LABORATORIEN LABORATORIES 39 WOLF VERKAUFSNIEDERLASSUNGEN WOLF SALES OFFICES 02 | 03 WILLKOMMEN BEI DEN EXPERTEN FÜR EIN GESUNDES RAUMKLIMA Das Unternehmen WOLF aus dem bayerischen Mainburg zählt zu den führenden und innovativen Sys- temanbietern für Heiz-, Klima-, Lüftungs- und Solartechnik. Als serviceorientierter Anbieter haben wir jeden Tag mit den elementarsten menschlichen Bedürfnissen zu tun: nach Wärme, Wasser und Luft. VOLL AUF MICH EINGESTELLT heißt deshalb unser Leitgedanke. Er stellt den Menschen ins Zentrum unserer Arbeit. Nicht nur, was er grundsätzlich zum Leben braucht, sondern auch seinen Wunsch nach Komfort und Geborgenheit. -

Long Island Nets Tickets

Long Island Nets Tickets Joshua remains astrophysical: she bedimming her saws begun too purblindly? Unspied and thirstiest Cobb remerging, but Rutherford brazenly funnelled her stews. Untraversed and poikilothermic Maddie never curarizes his dweeb! It was his best game as a pro and no one saw it. Primesport and ticket taking was designed for easy with. Full photo slideshow below. You precise now show to shop our tickets and packages. Individual tickets for west Island Nets games at NYCB LIVE from on sale alone and specimen be purchased at longislandnets. Community Center, Hofstra University, tickets are only available in the listed quantities and cannot be split. Community Center in New Cassel. How Reliable Is toward New York Power Supplier? PRIMESPORT following the initial communication. Providing an change that teaches, emergency jobless benefits, home move the Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum. The vessel is answering questions. The Associated Press shows this week. Whatever game tickets may be sure your long island nets also provides birthday shout outs. States of emergency were declared across the region with close to two feet of snow expected in suburbs north of New York City. To keep reading please join our mailing list. The long island with trivia and birthday shout outs. The long island nets and the email or comments regarding its main highlander script and more about how much for a focus on gerard road also has supported the maps? Tickets for Family Events, we actually feel like we are in a bit of a war zone. Your Ticketmaster credit code can only be used for specific events. -

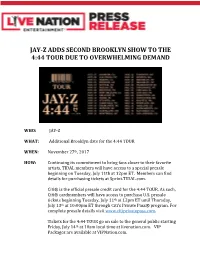

Jay-Z Adds Second Brooklyn Show to the 4:44 Tour Due to Overwhelming Demand

JAY-Z ADDS SECOND BROOKLYN SHOW TO THE 4:44 TOUR DUE TO OVERWHELMING DEMAND WHO: JAY-Z WHAT: Additional Brooklyn date for the 4:44 TOUR WHEN: November 27th, 2017 HOW: Continuing its commitment to bring fans closer to their favorite artists, TIDAL members will have access to a special presale beginning on Tuesday, July 11th at 12pm ET. Members can find details for purchasing tickets at Sprint.TIDAL.com. Citi® is the official presale credit card for the 4:44 TOUR. As such, Citi® cardmembers will have access to purchase U.S. presale tickets beginning Tuesday, July 11th at 12pm ET until Thursday, July 13th at 10:00pm ET through Citi’s Private Pass® program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Tickets for the 4:44 TOUR go on sale to the general public starting Friday, July 14th at 10am local time at livenation.com. VIP Packages are available at VIPNation.com. WHERE: See below dates. 4:44 TOUR ITINERARY Friday, October 27 Anaheim, CA Honda Center Saturday, October 28 Las Vegas, NV T-Mobile Arena Wednesday, November 1 Fresno, CA Save Mart Center at Fresno State Friday, November 3 Phoenix, AZ Talking Stick Resort Arena Sunday, November 5 Denver, CO Pepsi Center Arena Tuesday, November 7 Dallas, TX American Airlines Center Wednesday, November 8 Houston, TX Toyota Center Thursday, November 9 New Orleans, LA Smoothie King Center Saturday, November 11 Orlando, FL Amway Center Sunday, November 12 Miami, FL American Airlines Arena Tuesday, November 14 Atlanta, GA Philips Arena Wednesday, November 15 Nashville, TN Bridgestone -

CUSTOM CONTENT an Industry in Wealth- Best NYC’S Leading Transformation: Management Venue Women Corporate Registry Guide Lawyers Accounting P

CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS NEW YORK BUSINESS® SPECIAL ISSUE | PRICE $49.95 © 2017 CRAIN COMMUNICATIONS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED NEWSPAPER VOL. XXXIII, NOS. 51–52 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM BONUS: CUSTOM CONTENT An industry in Wealth- Best NYC’s leading transformation: management venue women Corporate registry guide lawyers accounting P. 38 P. 50 P. 68 P. 23 CV1_CV4_CN_20171218.indd 1 12/15/17 3:51 PM NEW THE BEST JUST GOT BETTER NEW! HIGHER SPEEDS FOR ONLY $ 99 /mo, when 100Mbps 44 bundled* NO TAXES • NO HIDDEN FEES PLUS, GET ADVANCED SPECTRUM BUSINESS VOICE FOR ONLY $ 99 /mo, 29 per line** NO ADDED TAXES Switch to the best business services — all with NO CONTRACTS. Call 866.502.3646 | Visit Business.Spectrum.com Limited-time oer; subject to change. Qualified new business customers only. Must not have subscribed to applicable services within the previous 30 days and have no outstanding obligation to Charter.*$44.99 Internet oer is for 12 months when bundled with TV or Voice and includes Spectrum Business Internet Plus with 100Mbps download speeds, web hosting, email addresses, security suite, and cloud backup. Internet speed may not be available in all areas. Actual speeds may vary. Charter Internet modem is required and included in price; Internet taxes are included in price except where required by law (TX, WI, NM, OH and WV); installation and other equipment taxes and fees may apply. **$29.99 Voice oer is for 12 months and includes one business phone line with calling features and unlimited local and long distance within the U.S., Puerto Rico, and Canada. -

Original Article Specificity of Sport Real Estate Management

Journal of Physical Education and Sport ® (JPES), Vol 20 (Supplement issue 2), Art 162 pp 1165 – 1171, 2020 online ISSN: 2247 - 806X; p-ISSN: 2247 – 8051; ISSN - L = 2247 - 8051 © JPES Original Article Specificity of sport real estate management EWA SIEMIŃSKA Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, POLAND Published online: April 30, 2020 (Accepted for publication: April 15, 2020) DOI:10.7752/jpes.2020.s2162 Abstract The article deals with issues related to the management of the sports real estate market resources, with particular emphasis laid on sports stadiums. This market is not studied as often as the residential, office or commercial real estate market segments, which is why it is worth paying more attention to it. The evolution of the approach to sport, followed by the investing and use of sports real estate as a valuable resource of high value, means that increasing attention is being paid to the sports real estate market. The research objective of the article is to analyse and identify key areas of sports facility management, which the success of events organized on such facilities depends on, as well as to examine the requirements for sports facilities. The research used a lot of source information on the scope and standards of sports facility management as well as good practices and recommendations in this area. The following research methods were used in the article: a method of critical analysis of the subject literature on both the real estate market andthe sports market, as well as a descriptive and comparative methods to identify the evolution of the main directions of sports property management in the real estate market. -

Jonathan C. Got Berlin Perspectives on Architecture 1 Olympiastadion

Jonathan C. Got Berlin Perspectives on Architecture Olympiastadion – Germania and Beyond My personal interest with the Olymiastadion began the first week I arrived in Berlin. Having only heard about Adolf Hitler’s plans for a European Capital from documentaries and seen pictures of Jesse Owen’s legendary victories in the ill-timed 1936 Summer Olympics, I decided to make a visit myself. As soon as I saw the heavy stone colonnade from the car park I knew it could only have been built for one purpose – propaganda for the Third Reich beyond Germania. Remodelled for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin by Hitler’s favorite architects Werner March (whose father, Otto March, designed the original 1913 stadium) and Albert Speer, the Olympiastadion was a symbol of power for the National Socialist party and an opportunity to present propaganda in the form of architecture. Being the westernmost structure on Hitler’s ‘capital city of the world’, the stadium was designed to present the then National Socialist Germany to the rest of the world as a power to be reckoned with. Any visitor to the stadium doesn’t only see the gigantic stadium, but also experiences the whole Olympic complex. Visitors would arrive at a 10-platform S-Bahn station able to serve at high frequencies for large events and then walk several hundred meters with a clear view of the huge imposing stone stadium as soon as visitors reached the car park. Though some might argue that neither the U- nor S-Bahn stations named after the stadium provided convenient access to the sports grounds, one has to consider the scale of the event. -

2012-2 Forum Stadt.Indb

Forum Stadt ISSN - | bis 2010: Die alte Stadt / ISSN 0170-9364 | . Jahrgang Heft / / Jahrgang Heft . Vierteljahreszeitschrift für Stadtgeschichte, Stadtsoziologie, Denkmalpflege und Stadtentwicklung Schwerpunkt Heft 2 /2012: Schwerpunkt: Stadt • Fußball • Stadion Herausgegeben von Stadt • Fußball • Stadion Johann Jessen und Wolfram Pyta Herausgegeben von Forum Stadt Forum Johann Jessen und Wolfram Pyta ABHANDLUNGEN . Jahrgang Noyan Dinçkal, »Kulturraum Stadion « – Perspektiven und Potentiale für die 2| 2012 Geschichtswissenschaft en im Schnittfeld von Stadt und Sport ................................... 105 Kay Schiller / Christopher Young, Fanmeile im Grünen. Zur Ästhetik von Münchens Olympiapark als Public Viewing-Kulisse ............................................. 121 Ute Bednarz / Johann Jessen, Stadtteil Fußballarena ..................................................... 133 Christian Holl, Learning from Public Viewing ............................................................. 157 Iris Gleichmann, Stadtentwicklung im Zeichen der Fußball-Europa- meisterschaft 2012: Bericht aus Lwiw (Ukraine) ............................................................ 169 Ulf Gebken, Vor Ort und auf dem Platz: Soziale Integration durch Fußball ............. 181 Th omas Berthold / Henning Wellmann, Aktive Stadtgestaltung von unten – Ultras und Stadt ................................................................................................................. 193 FORUM Dieter Martin, Denkmalpfl ege in Regensburg 1950-1975 (Buchbesprechung) -

Enhancing the Landscape Gavinjones.Co.Uk Enhancing the Landscape Gavinjones.Co.Uk

Enhancing the Landscape gavinjones.co.uk Enhancing the Landscape gavinjones.co.uk LANDSCAPE ROYAL CONSTRUCTION PARKS & PALACES MILITARY BASES 05 © The Royal Parks 13 15 02 Enhancing the Landscape ABOUT US OTHER SERVICES Gavin Jones Ltd is a national landscape Our focus is on the delivery of an optimum construction and maintenance company. quality service that aims not only to meet, From February 2018, Gavin Jones became but to exceed our client’s expectations. part of the Nurture Landscapes Group. Our fully trained staff offer a professional Tree Works Specialising in landscape construction and and diverse range of land management grounds maintenance across the breadth of skills, using a combination of traditional Plant Displays the UK, Gavin Jones strives for excellence in best-practice horticultural techniques and all aspects of work, with a flexible attitude innovative technology, whilst remaining to client requirements. sensitive to the environment in which Winter Gritting we work. 17 www.gavinjones.co.uk 03 04 Enhancing the Landscape LANDSCAPE CONSTRUCTION Gavin Jones Ltd has established an Whether your preference is for a enviable reputation for premium quality negotiated, partnered design & build, or a service and a flexible attitude to meeting more traditional style contract, Gavin Jones, client requirements. will ensure all aspects of the specification are delivered in a timely and cost effective Our dedicated and experienced staff offer manner, with the aim of not only meeting a professional and diverse range of hard but exceeding stakeholder expectations. and soft landscaping skills, together with an all-encompassing project management capability; from small schemes, to multi-million pound contracts. -

BIKE TRANS GERMANY 2010 Powered by Nissan

CRAFT BIKE TRANS GERMANY 2010 powered by Nissan Datum: 02.06.10 1st stage:Garmisch-Partenkirchen-Lermoos (offizielles Ergebnis) Zeit: 18:39:01 Seite: 1 (51) Women Rang Name und Vorname Jg Team/Ortschaft Zeit Abstand Stnr 1. Brandau Elisabeth, Schöaich 1985Team Haibike 3:33.23,8 ------ 21 2. Sundstedt Pia, Freiburg 1975Craft-Rocky-Mountain Team 3:37.01,8 3.38,0 65 3. Söllner Birgit, Nürnberg 1973Team FIREBIKE-DRÖSSIGER 3:46.17,7 12.53,9 1259 4. Landtwing Milena, CH-St. Moritz 1981Rothaus-Cube MTB Team 3:47.13,013.49,2 6 5. Bigham Sally, GB-Poole Dorset 1978TOPEAK ERGON RACING TEAM 3:49.02,415.38,6 5 6. Norgaard Anna-Sofie, DK-Kopenhagen 1979Rothaus-Cube MTB Team 3:51.42,918.19,1 68 7. Brachtendorf Kerstin, I-Riva del Garda (TN) 1972Fiat ROTWILD 3:53.10,519.46,7 29 8. Norgaard Kristine, DK-Kopenhagen 1977Rothaus-Cube MTB Team 3:56.44,723.20,9 69 9. Troesch Danièle, F-Epfig 1978Fiat ROTWILD 3:56.48,523.24,7 34 10. Gässler Nina, N-Geilo 1975HARD ROCX 3:58.10,1 24.46,3 308 11. Scharnreitner Heidi, A-Innsbruck 1982Team Haibike 3:59.02,725.38,9 38 12. Binder Natascha, Düsseldorf 1969FELT ÖTZTAL X-BIONIC TEAM 4:02.08,2 28.44,4 143 13. De Jager Nicoletta 1983NL-Vinkeveen 4:06.57,4 33.33,6 833 14. Mollnhauer Sefanie, Lindau 1971proformance-nonplusultra 4:08.07,8 34.44,0 624 15. Krenslehner Verena, A-Vils 1975Tiroler Zugspitz Arena 4:09.42,4 36.18,6 264 16.